It is de rigueur these days to reduce sexual politics to matters concerning toilets. I suppose in the long term, we have to be grateful to the writing of J.K. Rowling intended for adults, however stunted, for something, even if it is only to draw attention to the vast importance of the sexing of toilet spaces. It appears that Rachel Reeves has taken advantage of the new ‘changed Labour’ love-in with J.K. Rowling, which has (Reeves is sure to say (but hasn’t yet)) “absolutely nothing to do with her enormous wealth”, to raise concerns about the toilets in her Downing Street home (although presumably not the only toilet space there).

As Chancellor of the Exchequer of a modern Western democracy you would expect to have to entertain politicians who are male and female or non-binar. Is there any harm in offering a choice of means of urination in a room that is both private and lockable to intrusion, therefore? Yet here is the story turning up in the news:

Prior to Reeves being sworn in as the UK’s first female chancellor, Treasury officials had already discussed whether it was appropriate for the residence’s bathroom to contain a urinal, with Reeves herself telling the Spectator that she’s “not really” comfortable with one being in there. While early plans seemed to be in place to remove the offending receptacle, Reeves revealed on a recent episode of the News Agents podcast that it was still firmly in situ.

“I am the first female chancellor of the exchequer, the post has existed for between 800 and 1,000 years, depending on who you listen to,” Reeves told host Emily Maitlis. “I was wondering, Emily, whether you would like to, on the way out, come and have a look at the chancellor’s toilet to see the urinal that still is in there”.

…

Of course, there are some who think that the row is overblown; with many rightly pointing out that the bathroom still contains a sit-down toilet, which can be used by both men and women. It also doesn’t feel particularly dignified getting upset about a stranger’s toilet, no matter how esteemed their cheeks may be.

But there is something to be said for the symbolic value of removing a facility that can only be used by half of the population – specifically, the half that have exclusively dominated the role for the past millennium. Having a permanent fixture in place that caters to the office’s previous holders implies that only people who resemble those holders will have need for it in the future.

This story can only very tangentially connect to my life. Unlike Emily Maitlis, I am unlikely to be invited to use, or even view, her private toilets. but the tangent is one that interests me. It lies in the need of human beings to generate stories that appear in the public realm that have literally no public significance at all. This is such a story. We know that, were the Chancellor to order it, this change in her domestic appurtenances and furnishings would happen immediately and without question. Witness Boris Johnson’s lavish re-decorations – implemented without much fuss except in the companion decor – in his private residential areas as Prime Minister.

Yet generate a story we must – attaching to it great significance. That significance is generated by a plot. By this, I do not mean a conspiracy, but in this case, there may be a hint of that, for J.K. Rowling and her mindless gender-critical followers see plots everywhere – extending to people changing gender to enter toilets intended for people of the ‘opposite sex’. You would think sometimes that toilets containing people designated and tested as of one sex ONLY were the safest places in the world, but that is not the case.

They are not places whose primary intention is safety at all and have only become so because people imagine stories that happen between tick – going into the toilet – and tock – coming out of said toilet, other than the necessary business of urination or defecation. The issues of safety and its potential for compromised status come entirely from fantasies derived from our child-like fears and disgust about toileting habits.

I use tick-tock as the basic narrative because that wonderful critic, Frank Kermode, used it as the basis of all stories, for like them it is a basic beginning or genesis (‘tick’) and an ending or apocalypse (‘tock’). He writes brilliantly:

“Tick is a humble genesis, tock a feeble apocalypse; and tick-tock is in any case not much of a plot. We need much larger ones and much more complicated ones if we persist in finding ‘what will suffice.’ And what happens if the organization is much more complex than tick-tock? Suppose, for instance, that it is a thousand-page novel. Then it obviously will not lie within what is called our ‘temporal horizon’; to maintain the experience of organization we shall need many more fictional devices. And although they will essentially be of the same kind as calling the second of those two related sounds tock, they will obviously be more resourceful and elaborate. They have to defeat the tendency of the interval between tick and tock to empty itself; to maintain within that interval following tick a lively expectation of tock, and a sense that however remote tock may be, all that happens happens as if tock were certainly following. All such plotting presupposes and requires that an end will bestow upon the whole duration and meaning. To put it another way, the interval must be purged of simple chronicity, of the emptiness of tock-tick., humanly uninteresting successiveness. It is required to be a significant season, kairos poised between beginning and end. It has to be, on a scale much greater than that which concerns the psychologists, an instance of what they call ‘temporal integration’–our way of bundling together perception of the present, memory of the past, and expectation of the future, in a common organization. Within this organization that which was conceived of as simply successive becomes charged with past and future: what was chronos becomes kairos. This is the time of the novelist, a transformation of mere successiveness which has been likened, by writers as different as Forster and Musil, to the experience of love, the erotic consciousness which makes divinely satisfactory sense out of the commonplace person.”

― Frank Kermode, The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theory of Fiction

I could even try a verse on this, in syllabics (7 like Thom Gunn I read in his latest biography, speaking of the Touch period):

Tock-tick, tick-tock, Tick!

Delay that world ending tock

Fill my time with fears that lock

Me in fear and let time stick.

And stories of the dangers – even cognitive and affective imaginations ones only, such as those that might constitute Rachel Reeve’s feeling ‘uncomfortable’ and sharing that with Emily Maitlis, have to be important enough to fill up the space between the ‘tick’ of her opening her own domestic space and the ‘tock’ of her coming out again. Fill the space perhaps completely with inventions that trivialise rather than highlight the dreadful history of the patriarchal order and its long alliance with capitalism. The chancellor is in a position to change the lives of women in many ways. But it all comes down to the amazingness of her own position as first female Chancellor, as if female Prime ministers in control of Chancellors had not already existed, and shown, especially in the case of Liz Truss, that they too can be hierarchical and unfair like men unless structural change occurs that has an effect on all women and men. Kermode calls this invention of stories the transformation of ‘that which was conceived of as simply successive’ into that which ‘becomes charged with past and future: what was chronos becomes kairos‘

The difference between these concepts in Greek is that between Time considered globally as a succession of unfulfilled and oft insignificant moments and a period in which the lucky and the wily can take advantage of opportunities thrown up in time: see this link for a blog on this.

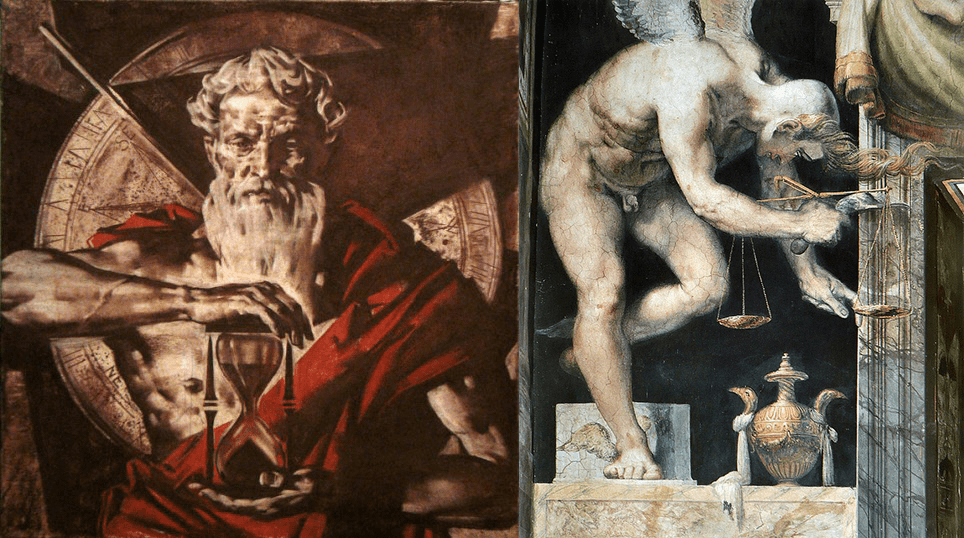

Kairos on the right is keen to pick up on any opportunity. He has one strand of hair on his head so the lucky abnd fortunate can grasp him. Chronos just watches time go by and people die successively.

What this story means to me is that politicians in the interests of focusing politics on them.not the issues fill.the hole in which it is necessary to stop giving social hope for change. Such hopex once hung on a Labour victory. Now we must get used to the normalisation of silly stories about people who have taken opportunities to grasp power and whose main aim will be to keep it at whatever cost, especially cost to those who needed real hope.

So! Have you read the one about the Chancellor’s problems (aesthetic and associational rather than practical or to do with excretion as such!)? Why not give it a miss! We need to protect and enlarge our democracy. We need to scorn stories not worth the time they occupy in the public media except in allowing those with power who hold the public stage to hold it just a little longer. These stories aren’t even funny but mock-serious in a way that has malice in its sting.

All my love

Steven