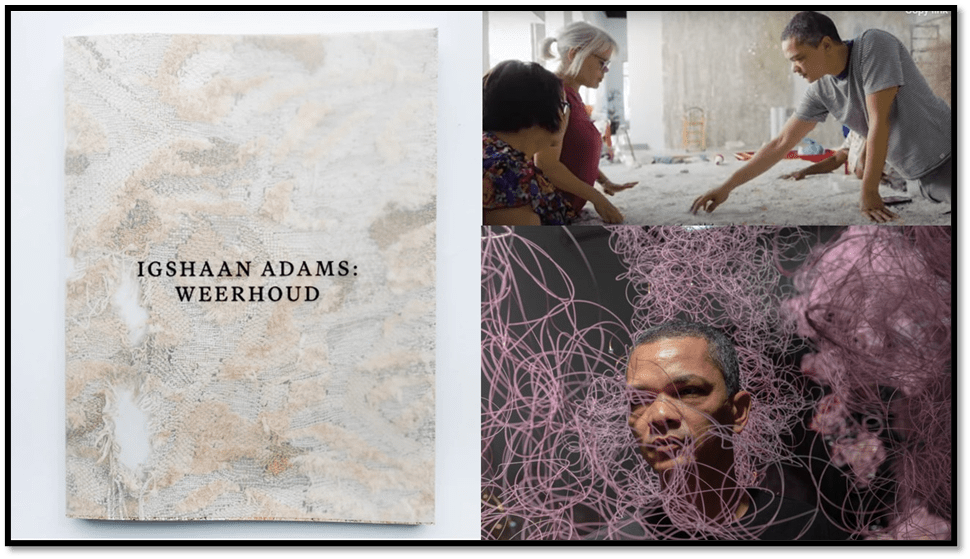

Whilst working on the subject of trauma and pain at art school, Igshaan Adams (born 1982) asked his teacher what his work said about him. ‘She said: “it says that you like to make your trauma beautiful. You like to beautify your trauma”’. [1] This is from a series of blogs on a day visit to see the art in exhibitions at the Hepworth in Wakefield and The Yorkshire Sculpture Park at Bretton Hall Country Park. This is number 1 of 6.

Trauma is multi-faceted in the work of Igshaan Adams, and no artist is a clearer example of how intersectionality as a concept in the analysis of how the relative power of social groups manifests itself. For instance in an earlier exhibition at the SCAD (Savannah College of Art and Design) Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia in the USA in 2022-23, he used the ‘battered linoleum floors he sourced from the homes of working class, mixed race communities of his native Cape Town, South Africa.

Igshaan Adams, Installation View, SCAD Museum of Art. Photograph by Erin Jane Nelson. Available at: Erin Jane Nelson (2023) ‘The Importance of Ritual: A Conversation with Igshaan Adams’ in’ Burnaway’ (Online FEBRUARY 21, 2020): https://burnaway.org/magazine/igshaan-adams/

Interviewed by Erin Jane Nelson for Burnaway, Nelson introduced his work by saying:

Both the artist and the floors have themselves witnessed the frenetic and violent reality of the racially oppressed communities that endured Apartheid and its residual cultural impacts. Though beautiful, rich, and deeply immersive, Adams’ exhibition comes from a difficult personal history and yearning to heal generational trauma’.[2]

The approach we should take to ‘difficult personal’ (and psychosocial)’ history’ should not though treat the people the art celebrates as merely victims, for their history of community and its positive are also a product of oppression and reaction to it and again show that an intersectional reading is necessitated.

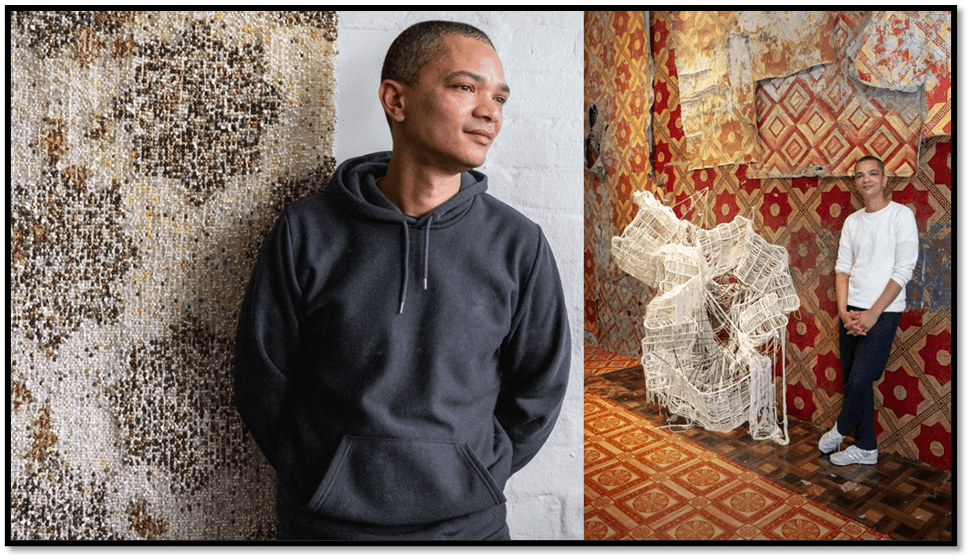

However the intergenerational trauma in the example above clearly focuses on the trauma that is a product of cyclic transmission down generations of racial and class oppression, poor housing and poverty. Sometimes his take on marginal communities is even more specific as in his support and learning from communities of artisanal weavers, which again links to the Sufism he found in such Muslim communities of poor weaver communities, together with communal ritual practices such as ‘Zikr’, which he also found in those communities.

Indeed, Nkgopoleng Moloi argues in an essay in the Hepworth exhibition catalogue that weavers, like dancers and his own family are in ‘profound connection’ to him: he finds in them the stuff of his art which is based in the experience of substance, matter or material (which ever of these labels is mist appropriate, ‘in motion’. Sometimes the material is the body, which also supplies the dynamic of movement, sometimes with that of a machine (a loom) or an instrument (musical or otherwise) but at other times the material that are necessitated in waving – strands of different kinds moved into the formation of the warp and weft of the product or the materials that capture more permanent, if yet fragilely, the motion of the human body in dance.[3]

No commentator should even think of simplifying it otherwise. However, as a queer artist, Adams experiences and uses the intersection of his queerness in the situation of South Africa, both before and after the end of Apartheid, and the experience of heteronormativity and homophobia across different communities of race, class, ethnicity and religious belief. The latter matter a great deal to Adams whose spiritual aspirations in his work and life are connected to other levels of both trauma and hope. However, all experience connects somewhere in the web of social interconnection and intersection and for me Adams is particularly important in this respect in developing queer art without ignoring the other contexts of both oppression and resilient energy.

For instance Moloi concentrates on the life of the material in the everyday as the stuff of social practices – like weaving and dancing – and interprets some works with an eye to these that miss obvious reference queer experience, as in their analysis of the 2018 work Bent, which is in the Hepworth exhibition. I will illustrate it (my photograph of the photograph in the catalogue) before giving Moloi’s reading of it:

Moloi says this of Bent, focusing on it as a commentary on the fragility and vulnerability of material to the ‘passage of time’.

Weerhoud features artworks that subtly evoke a sense of fragmentation and the passage of time. Some pieces bear traces of exposure to the elements, hinting at a weathered past. Others show signs of intentional damage or tearing, their imperfections proudly on display as part of their essence. These works convey a delicate balance, suggesting they were once part of a larger whole, now fragmented and vulnerable. This theme is exemplified in the work Bent (2018), a piece that explores the concept of fundamental structural change. Like a flower bending toward sunlight, altering its shape in response to its environment, Bent illustrates how external forces can subtly transform the essence of an artwork.[4]

Sensitive as these remarks seem, I think the overuse of the word ‘essence’ mars it; ‘essence’ being anyway a very slippery word. ‘Essence’ sometimes denotes an a-priori notion of an idea of what a thing is that precedes its existence as a material thing, like Plato’s ideal forms or the prototype or ‘blueprint’ of a thing in a Maker’s mind. At other times an ‘essence’ denotes a thing to which a thing with all its imperfections can be ‘reduced’ or distilled, either materially or intellectually. In whichever form, however, the essence of a thing is considered a more perfect representation of the thing than the thing as it exists and acts, reacts or interacts in the mundane world with other things in its environment.

I suspect a ghost of such ideas underlies Moloi’s notion that the material artefacts of Adams’s work appear, even if they are not as mere parts of a whole that has either been lost through time or not yet completed in time. Material things therefore are intrinsically ‘fragments’ and subject to further losses when exposed to the environment. Moloi’s thinking around ‘essence’ however remains contradictory in my reading of them, since if a thing can transform in its ‘essence’ (as a ‘flower’ or ‘artwork’ does by being worked upon externally) how is that moment of change of essence comparable to the ‘imperfections’ caused by such violence or decay being ‘part of its essence’ because it ‘wears them proudly’. I may misunderstand Moloi completely, for the work published by that writer is clearly not in a tradition where essence matters as much as this paragraph suggests. It is clear from Adams writing that he too thinks of his work as either ‘remnants’ of, ‘or in some cases it feels like they are fragments of a larger whole a section oof something much greater’. Adams even uses the word ‘essence’ in this context, but it not in terms of the essence of thing represented but of a thing that has little material realisation and no relation to what exists but only to some state of being before, and after existence or transcendent of it. His quotation above continues thus: Again, it relates to Sufi’s concept of no separation. We can never be separated; as human beings we are all part of the same essence’.[5]

But why do I torture out this concept in relation to what Moloi says specifically about Bent as an example of Adams’ best work on the fragmentation and vulnerability of things in themselves. I think it is because I want to insist that Bent, though it may be about the process of change, is not about a process that happens external to things and beings and without the cooperation of the thing itself. It is not a process of victimisation, though it might include that experience, but of becoming through reactive performance in relation to forces acting on it. Bent is, after all, as it must be a piece about bent as a label, like queer, that people take on and render a positive sign of self, achieved in life performances. In the earlier interview I cited, from 2023, Adams is clearer about this. What we are, even if we are ‘bent’, is a product of ritualised life-performance in everyday life that remakes us and whatever to be ‘bent’ means as a celebration of positive and active self, moving through, touching others and things and, as we go, actively remaking the world by doing, by performing as we must to demonstrate our values as we make them.

Igshaan (I): I do think about the performance of self in everyday life from a spiritual point of view. I consider myself to be constantly performing in this world, playing out this identity in this life experience. I find this quite healthy because it gives me a bit of distance. I am allowed to then look at myself and observe myself.

Erin (E): Like catharsis.

I: Yeah, catharsis. I think it’s very healthy because it keeps the focus inward rather than externally in pointing fingers. So in that way, I would say sure performance or performative aspects of identity, but mostly I just love making things. I like taking the wire and turning it into something. I like to keep my hands busy with just forming and making and producing and turning one thing into another. I also quite enjoy the idea of bringing importance to something that would’ve been overlooked or considered valueless. I relate to that idea as a person because I felt a bit devalued, but I had the opportunity to change that.[6]

What Moloi’s passage omits is that being ‘bent’ is neither an essence nor a form of existent ‘being’ but a manner of doing or performing in the world, even in your resistance to changing the way you are performed upon. You may be labelled as ‘bent’ but it is how your fibres interact and work when used that matter, not the prior labelling for then the thing named ‘bent’ defines itself through performance. Read Adams’ words again, they are about the remaking of queer identity at every moment of our everyday interactions, not accepting but changing what is thrust upon us to something that is ourself not other:

… just forming and making and producing and turning one thing into another. I also quite enjoy the idea of bringing importance to something that would’ve been overlooked or considered valueless. I relate to that idea as a person because I felt a bit devalued, but I had the opportunity to change that.

The bent or the queer are precisely categories born out of an exterior labelling, even elaborate ones like diagnosis, that describe an essence EXTERNALLY. In our performance we make them anew and proud. We may have moved some way from the artwork so let’s look again:

There is no doubt that Bent bears the signs of both wear over time and violent damage, but it is also being made and remade by the hands of the artist over its life, ending only at the point at which it no longer performs to ensure its survival, The makings are themselves curious bends in the textile that create patterns not seen where bends do not occur, Tears, rends and collateral damage to find shape and definition that are new and renewed, even the cascade of fabrics in a free fall add to the dynamism and flow, and might be reshaped depending on the flow of air wherein they sit or stand or hang. It offers cover and protection whilst itself being in such need. To look at it is to compare the stories of its traumatic history with one’s own, in the creases, wrinkles and wounds of the body, the slippages and cascades of mental disintegration held back by some performative holding operation.

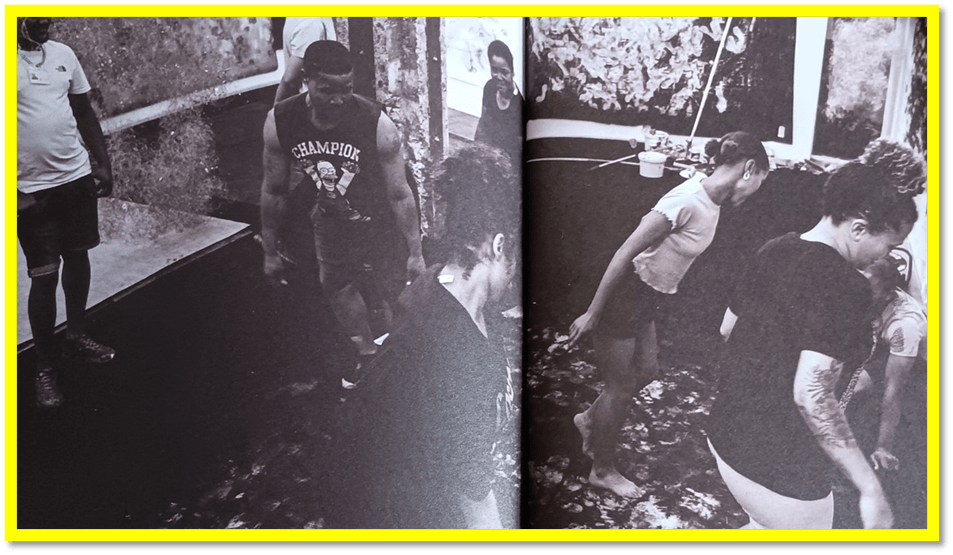

This is, I would argue about queer biography / autobiography The central new work in the show is a textile hanging across a whole wall that was made by the feet of a queer dance troupe in a dance involving much foot shuffling being recorded on an oiled template and then used as a design for the weavers. Here is a representation of the dance from the catalogue:

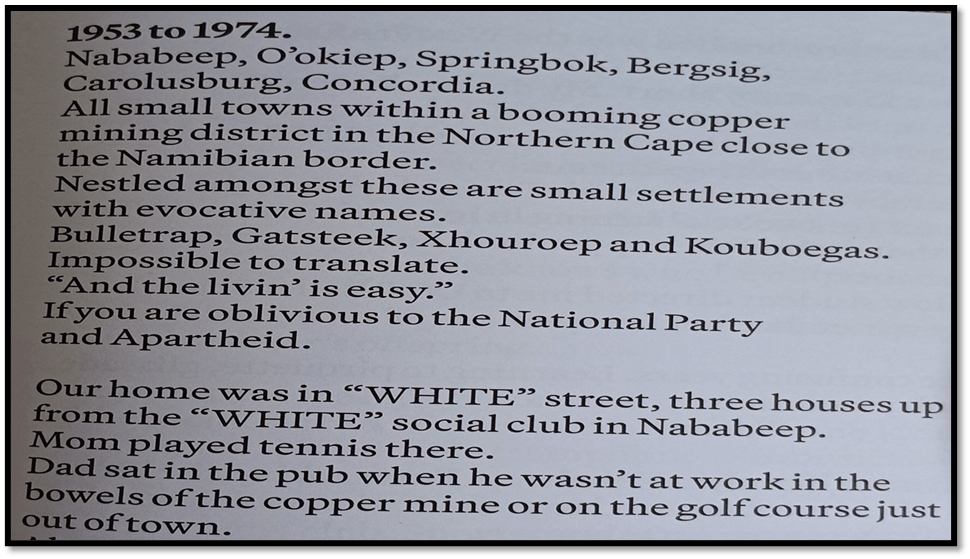

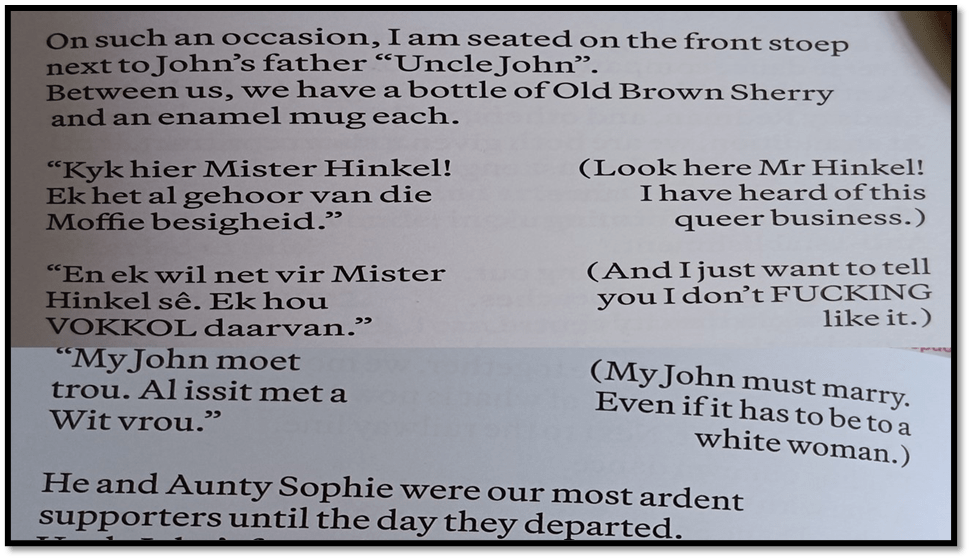

The primary member of the dance troupe, Alfred Hinkel, also contribute an essay to the catalogue in which he recounts an account woven of episodes from his life and that of his now life-partner, John Linden, Adams’ uncle. This is a life created by continual interactions growing up in the framework of Apartheid, and the dominance of Afrikaans ‘white working-class’ culture and language for Hinkel, where even the name of your street placed you and removed you from certain experiences and gave you privileged access to others. These were the shaping influences of Alfred’s life, though his ballet classes appalled his father. Here is the opening:

Yet introduced to John Linden’s father, the fissure of his life opened up in a conversation in Afrikaans, or at least it seemed so – but for the fact that the ‘moffie’ word once negotiated, ‘Uncle John’ (the name he used for his partner’s father) became woven into a different and more cooperative life despite the existence of apartheid laws.

The weave – warp and weft – of experiences creates new ways of understanding the ‘bent’ and the ‘queer’, both of which words ‘Uncle’ would translate as Moffie. The bent like the artwork Bent is domesticated. As I said above, this is, I would argue, about queer biography / autobiography but not just that. The relationship between notions of touch, fabrics and the textures of textiles have long been part of folklore responses and rarely get studied in the academy (as in this link) and those questions are raised in the psychology of human mutual touch also. The prohibitions baked into heteronormativity about touching between males have a wide range of potential for damage. For instance Adams speaks in the Nelson interview about a piece of performance art in which his father, Ameen, had to touch his son’s body in a repeated ritual of preparing his supposedly dead body for disposal. For Adams mutual touch, even under this grim fiction was about repairing the texture of a relationship through touch, making with the hands:

Igshaan Adams: …. I wanted to know certain things about myself and so I looked to my family. / I did a performance with my father where he washes and prepares my body as if I had died, which was about creating a moment for the two of us to kind of recenter our relationship; to forgive. Something died in that process, perhaps the younger version of myself that needed to fix the relationship with my father, because I saw him as the monster. He was a drug addict; he was violent. I witnessed my mom being brutally beaten on a daily basis by him. So, I hated him in a sense and I hated myself for being a part of him, coming from him.

In learning through that process the ‘importance of ritual’, he describes the ordinary as redemptive but not by conscious intention or will. Erin Jane Nelson says to him: ‘I was wondering if you see your practice as trying to break down traditional ideas of masculinity–if it feels radical for you to change the way that men can touch each other and relate to their families?’ To which Adams replies:

Absolutely. I think that really came through in the performance with my father because he wasn’t trying to act or get attention. People kept asking him how it was to see his son as a dead corpse wrapped up. He said “well actually he wasn’t dead, so I know he’s not dead. I have a job to do,” so to him it was like washing dishes.[7]

The central point here is that performing our lives together, even in fantasy and roleplay, gets us touch with the texture of our mutual skin and clothing without any prior conscious mentalisation. Doing precedes being as a human, as being precedes any fatuous abstracted essence. All of it is experienced in touch between our bodies and other things and bodies in working together to do and make. And that touch can be imagined even, as Adam’s works invite the desire and imagination of touch.

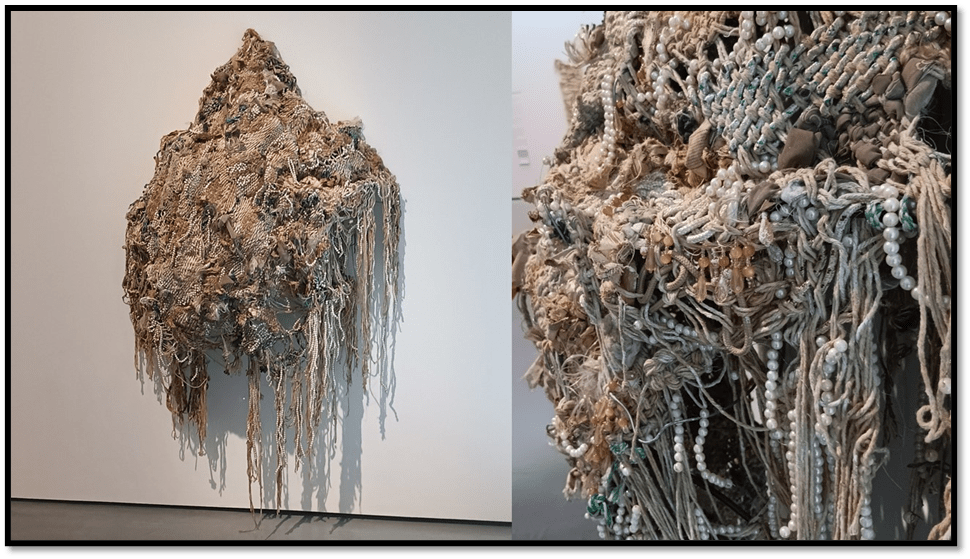

Laura Cumming often understands such moments. Here is her description of the work named Ouma (grandmother) which entranced me as it did her:

A collage of my photographs of ‘Ouma’ or is it ‘Empty’ The description fits both.

A downpour of open warps, in silvery twine, glints with a weather of shining beads, pearls, shells and stone chips to bring you straight into a deluge. A cascade of nylon rope, tiny dark elements caught up within it, suggests both crisis and waterfall. An extraordinarily complex structure of lace, cotton thread, fine chains and tiny jewels, suspended and bodying forth from the wall, folds and curves and appears to open its two arms wide. Ouma – grandmother – it is called.[8]

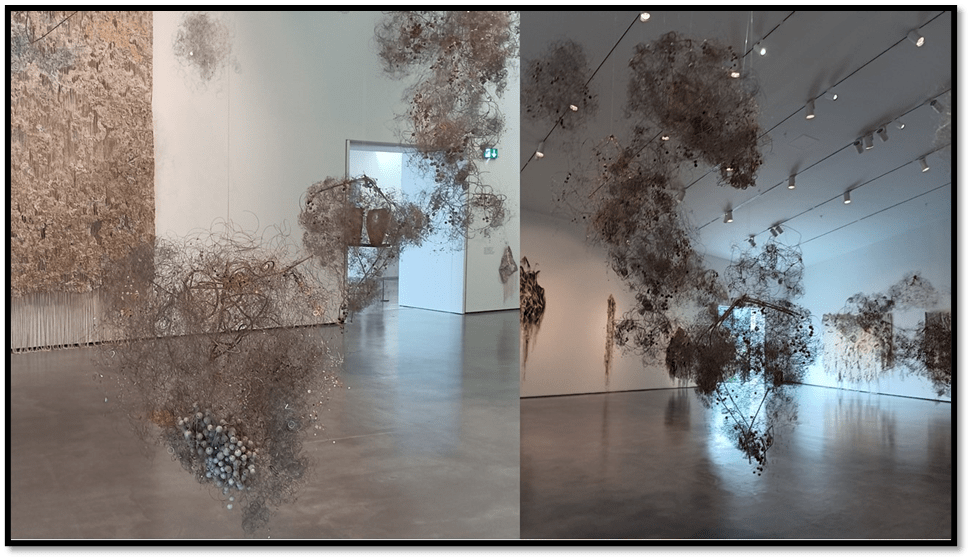

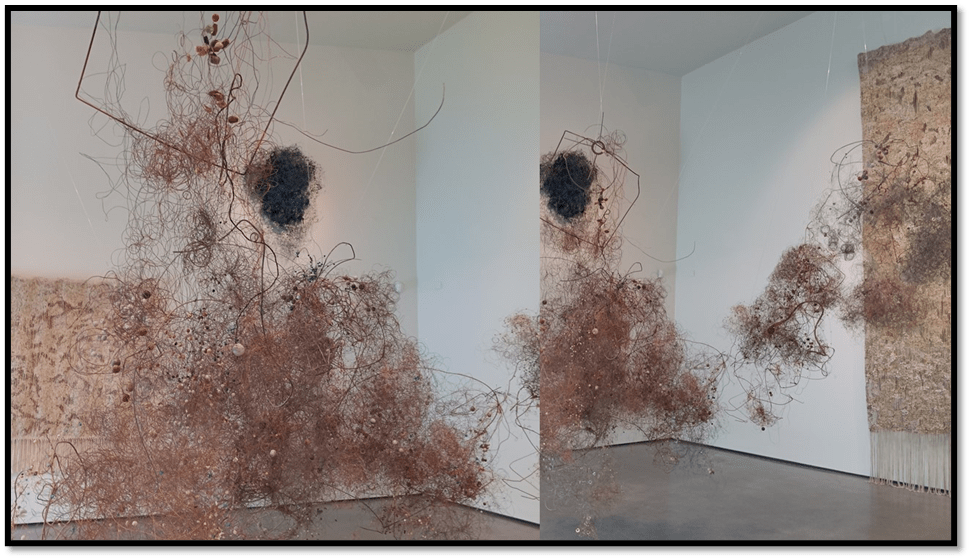

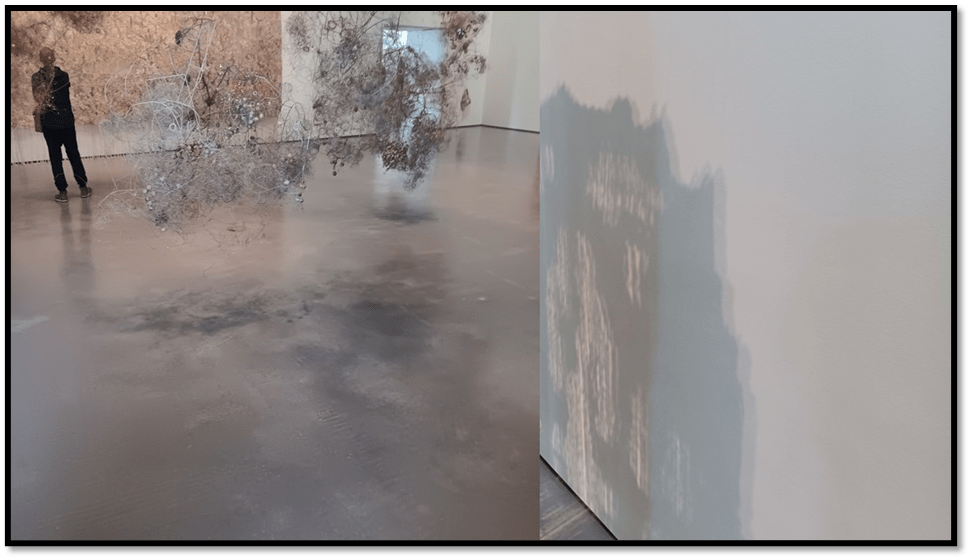

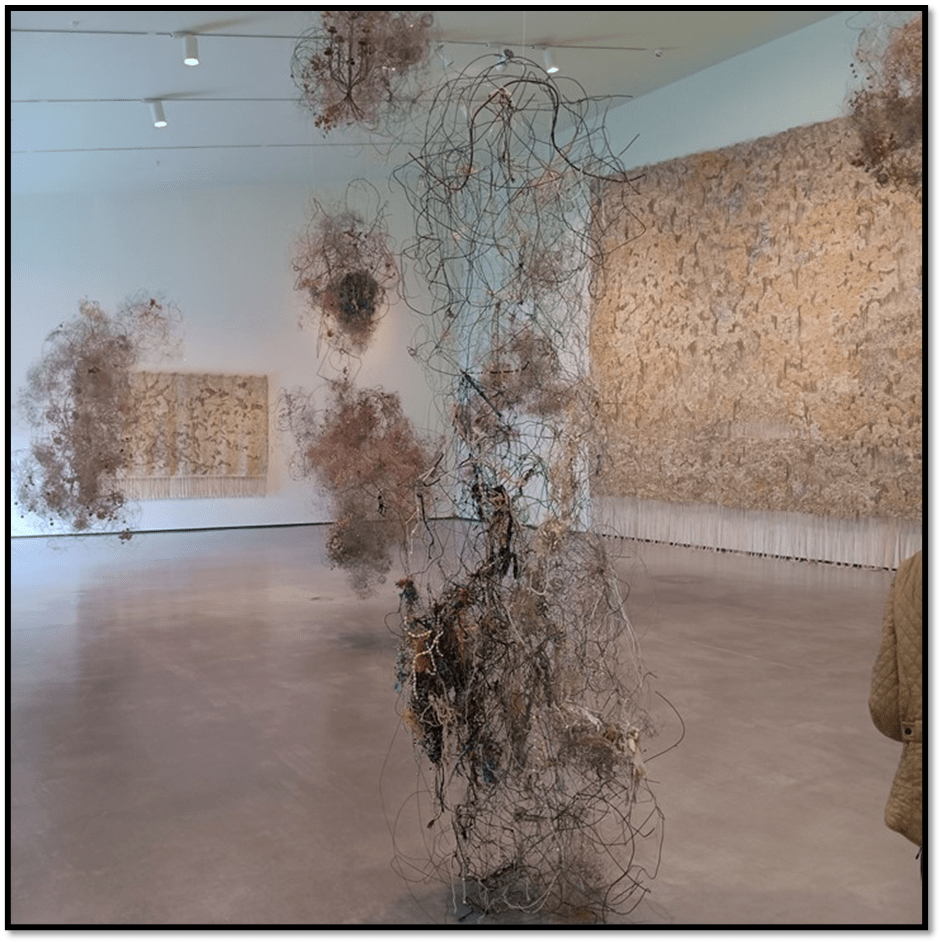

Good writing like this evokes the feel of its employed metaphors – the feel of a downpour of rain, the overwhelmed feeling of total wetness that may follow. The appearance of the object’s open arms is also the imagined feel of being invited to embrace the warmest thing you know whilst also feeling the resistance of its clothes and jewellery, the open and closed, and the rough and the smooth, the desire and repulsion in the experience. Another piece Ameen finds his father both vulnerable and damaged and yet seeming to promise repair of its tatters though imagined touch. The photograph Cummings article uses to capture the show feels more numinous and less varied in the responses to touch than my memories, even those captured in my photographs, though all show how the gallery transforms into a mess of substance of varying densities that cause your need to navigate between them – both in want and fear of touching and being touched by the pieces that radiate into apparent empty space. Here is The Observer’s picture. Taken on a much brighter day or with the photographer’s additional lighting:

‘Featherweight yet as momentous as a meteor shower’: Igshaan Adams’s Weerhoud at Hepworth Wakefield. Photograph: Mark Blower

Compare it with a few of my photographs from which I created collages:

As you see the effects are not just of visible light or physical lightness. They vary so much, the whole room is experienced in a multitude of complex interacting feelings and imagined sensations.

As I read more about these wondrous artworks, the more do I see in the ways that they might be talked about, but I still remember best walking into the gallery, almost the first we saw after that in the atrium, and feeling stunned by the beauty, the wholeness of a room full of fragments, actually curated to act as an artwork itself as a container for different, overwhelmingly so, individual works, I was pleased to be there with my dear friend Catherine, who had a background in textiles and almost immediately engaged the friendly young woman on duty in the room, whom Catherine soon guessed to have a similar background in that subject. I caught them talking as I looked around unable to fathom the technicalities they explored in their talk.

For me the exhibition was a mixture of awe and terror – but a thing held together by beauty. In the quotation in my title, Adams seems to feel recognised in an early teacher’s comment that he liked “to make” his “trauma beautiful. You like to beautify your trauma”’. [9] I want finally then to think about how trauma, which the mental health charity, Mind, explain thus:

Trauma is when we experience very stressful, frightening or distressing events that are difficult to cope with or out of our control. It could be one incident, or an ongoing event that happens over a long period of time.[10]

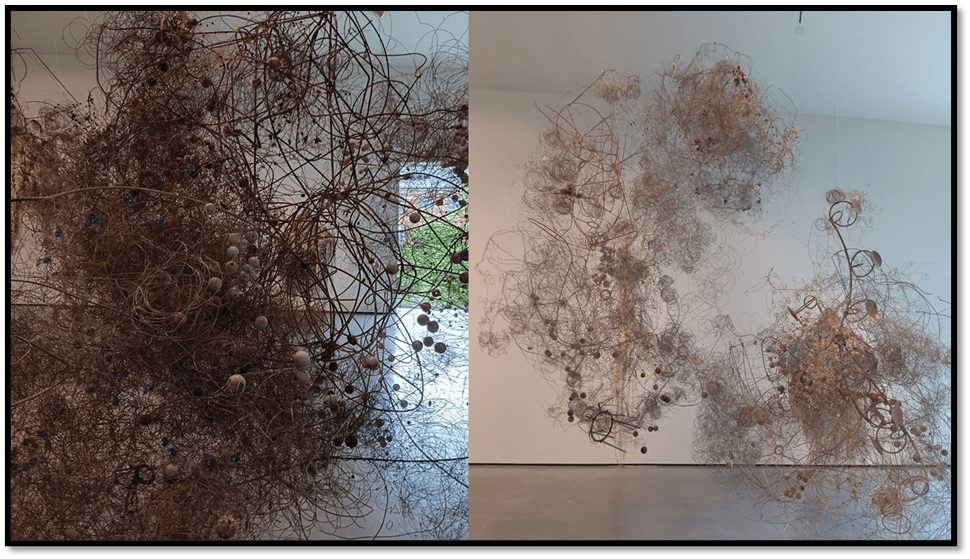

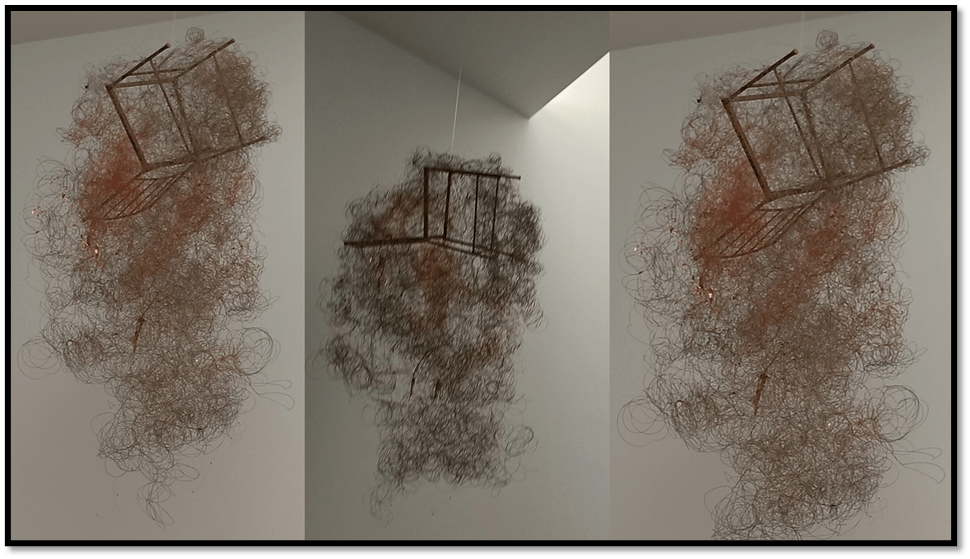

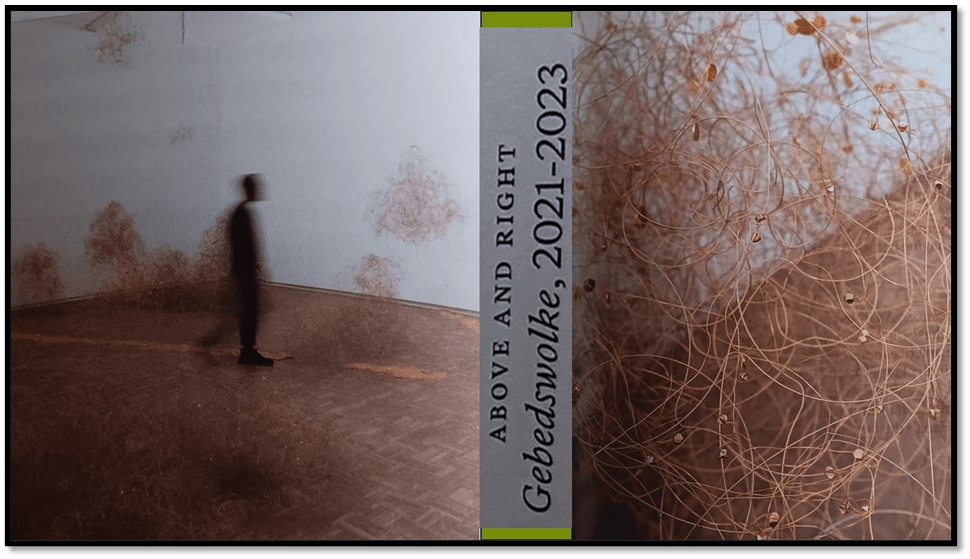

These words give little sense of how it feels to be out of control, nor the weight on the person experiencing, and re-experiencing the core of the trauma, perhaps even constantly re-enacting that trauma, feel, however the sequelae of trauma express themselves and for what duration over a life and in their nature as episodes. To be called upon to ‘beautify’ such material would seem invidious for how can the inexplicable and uncontrollable be ever considered beautiful. For beauty, at least those versions cut off somewhat from the energies of desire, is often associated with the very opposite of these experiences – something whose regularities smooth out and pacify the emotions. The explanations offered in the Weerhoud catalogue are brilliant in their invocation of material concept that carry s like cloud, especially clouds of dust – the smallest remnant of things now lost to consciousness as a linking and almost but never fully numinous envelope or network. Such clouds link things lost in these clouds, even larger and more recognisable objects like chair frames without revealing their content, which is, in all of us associated to some traumatic loss. Take these example. They contain a chair that has fallen or is falling, or burning, taking with it an unrevealed memory.

The chair on the other hand may offer a comforting idea, emergent out of otherwise unspecified loss of varying density. For the Wakefield exhibition, Adams explains his method as an assemblage of scares, traces of the lost or of a wound. He says:

You carry the scars, but no-one can see them. They are in our memories, and our bodies, but they remain unseen. Sometimes we don’t even see them ourselves. The only scars that are left are sometimes small traces. Marks on floors, walls, furniture, where violence happened. They are like witnesses, silent witnesses.[11]

Sometimes the pieces trapped in the clouds are large, and sometimes bound together in the memory of an incident hard to reassemble as below.

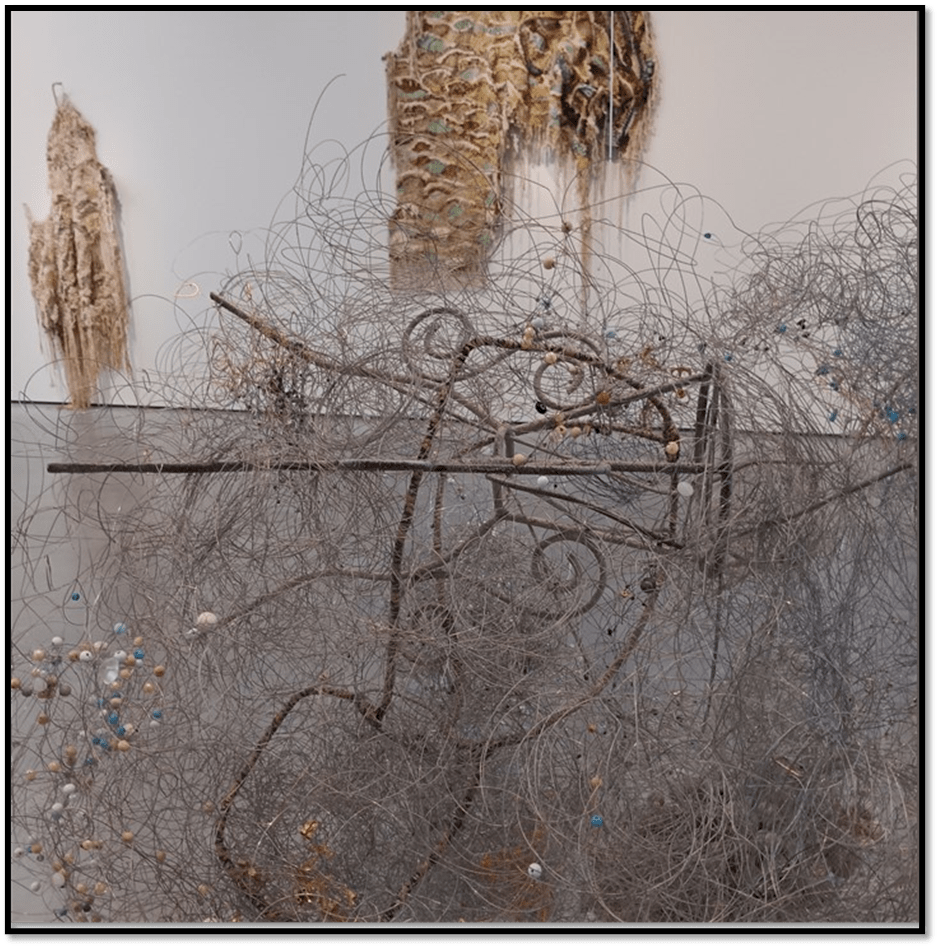

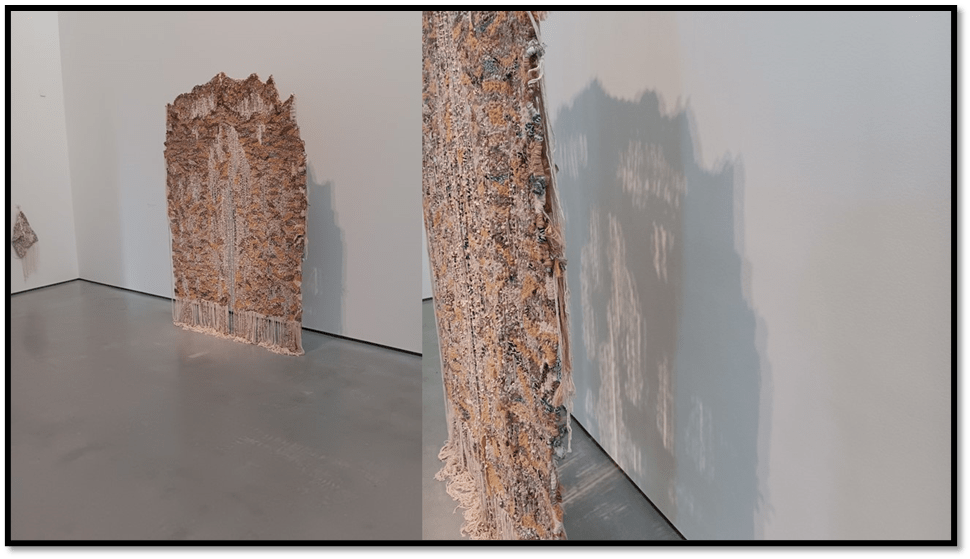

At other times two items of different kinds of individualisation as below have their margins unclear partly because of the variation in materials used to structure them but sometimes because they cast shadows of themselves that enhance or detract from these densities as below. Ouma (left) seems enlarged by its shadow.

Sometimes, yet again, the fall of a shadow from the object that has the resemblance even of a stain from some past accident involved a spillage of fluid (blood even), whether a confluence of hanging clouds of unequal densities or the shadow falling behind a flatter lace-like (in structure if not texture) tapestry can be attended to more than the object and may indeed be the true object – of either or both trauma or beauty.

The tapestry’s shadow seen above on the left of the collage looks like something aligned to Gothic fantasy when seen with the tapestry that casts it, as in the collage below. It doubles and solidifies what is before you notice the shadow more flimsy.

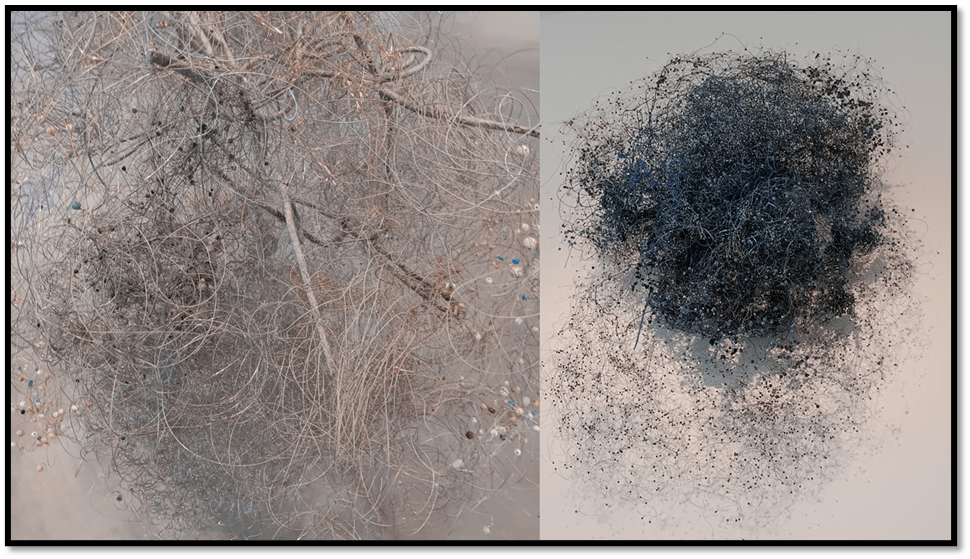

Often entanglement defies the visibility of the structure of a piece composed of many networked strands or wires-, or where holes in the piece are filled by clusters of beads or separated out by differing constellations of them.

In the catalogue slow release photo capture is used to enhance the effect, although for me it dissipates it, although the structure of the Gebedswolke piece does seem clarified – if only to show that it is only the more complex in the detail below.

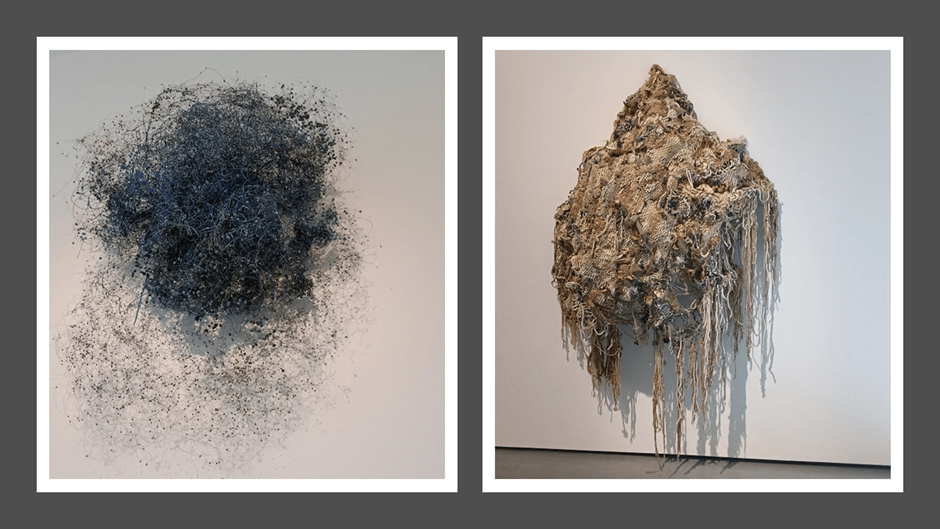

It is all the better perceived in the picture of piece (my photograph) and detail from the catalogue in the picture of Wolkies blaas 2020 below. This piece, mounted as it is high on a wall, intrigued and frightened me – it is beautiful but extremely dark as if one were staring into the eye of the trauma itself.

Wolkies blaas 2020 with detail of periphery of cloud

Writing this piece has had its difficulties. The Afrikaans word Weerhoud means withdrawn or withheld and I feel in myself the sense that I want to say more than in the end I dare, and, when I examine this feeling more recognise that is in part because I do not know what the content I want to say but have withheld actually is. Is this a sign of connecting to the trauma of the pieces or of the fear of failing to so? I do not know. It is possibly anyway, a question definitive of Igshaan Adams artwork anyway, which works to stun rather than to promote intellection of a shallow sort.

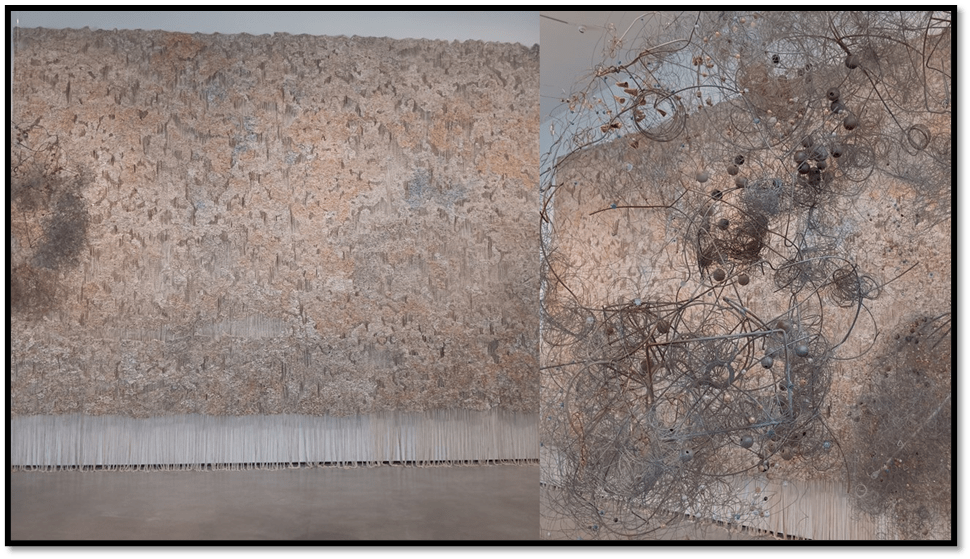

However, let’s end by thinking about the definitive work of the collection, according to Nkgopoleng Moloi in her essay ‘Tracing the Body’s Language’ in the catalogue, a wall tapestry based on the traces of dancing bodies in his uncle John Linden and John’s life-partner Alfred Hinkel dance troupe the Garage Dance Ensemble. Moloi’s is a brilliant essay, despite my nit-picking earlier, where she argues that ‘body’ has a tripartite meaning and leaves traces in the work of each meaning – the physical body the socialised body, and as a symbol for border-crossing communion and communication. It’s title is Jaime-Lee, Byron, Dustin, Farrol, Lynette, taken from the names of the body of dancers who initiated the work. For Adams dance in its rhythmic, affective and mobile components of meaning is like weaving itself. Here again I think exploration of meanings has to be somewhat withheld. But even seeing it raises initial problems for what we are seeing in Weerhoud depends on the angles and distances from which we see and a kind of selective artifice of our perception. See for instance my collage below.

We see more of the tapestry in the shot on the left but even then a dark and somewhat sinister dark cloud on the extreme left intrudes. On the right, we see it only through the windows or holes offered by another great work. All of this matters, for seeing things alone is, when it is not an artifice sometimes curated into art galleries, also an illusion. Works are seen through each other. See this particularly in the room view below, where the social dance tapestry on the left wall dwarfs the Ameen tapestry on the right, that named after his father. Between them connecting and separating them is the wonderful mass of apparently random but in truth dancing threads and wires of multi-colour that is Oorskot (2016)

In my detail photograph (left in the collage below, we see the ear patches which represent the traces of dancing feet but miss the startling colour of the threads and beads and chains that interwoven in dance form the solid intermediate parts (in my photograph of the detail given in the catalogue that follows. In all what is random is in fact ordered though the rationale of the order is withheld, again perhaps as in Sufism. Pattern prevails despite itself, it is the difficult to pattern motion of bodies through time and space: it is dance, it is weaving.

Please see this exhibition. It fills only ONE of the nine rooms of the Hepworth Gallery, but it makes it difficult to see the rest were not the rest such great works as they are by Ron Moody and Barbara Hepworth to name but two. There are more blogs to follow.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxx

[1] Igshaan Adams interviewed by Laura Smith and Marie-Charlotte Currier (2024: 127) ‘A Conversation with Igshaan Adams, April 2024’ in Marie-Charlotte Currier (ed, with design by Cecilia Serafina) Igshaan Adams: Weerhoud (Catalogue) Wakefield, The Hepworth, Wakefield.

[2] Erin Jane Nelson (2023) ‘The Importance of Ritual: A Conversation with Igshaan Adams’ in’ Burnaway’ (Online FEBRUARY 21, 2020): https://burnaway.org/magazine/igshaan-adams/

[3] Nkgopoleng Moloi (2024: 17, 19ff respectively) ‘Tracing the Body’s Language: Movement in Igshaan Adams’s Practice’ in Marie-Charlotte Currier (ed, with design by Cecilia Serafina) Igshaan Adams: Weerhoud (Catalogue) Wakefield, The Hepworth, Wakefield.

[4] Ibid: 19

[5] Adams cited in’ Igshaan Adams interviewed by Laura Smith and Marie-Charlotte Currier (2024: 123), op.cit.

[6] Erin Jane Nelson op.cit.

[7] Erin Jane Nelson op.cit.

[8] Laura Cumming (2024) ‘Ronald Moody: Sculpting Life; Igshaan Adams: Weerhoud; Bharti Kher: Alchemies – review’ in The Observer (Sun 14 Jul 2024 09.00 BST) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/article/2024/jul/14/ronald-moody-sculpting-life-hepworth-wakefield-review-igshaan-adams-weerhoud-bharti-kher-alchemies-yorkshire-sculpture-park

[9] Igshaan Adams interviewed by Laura Smith and Marie-Charlotte Currier (2024: 127) op.cit.

[10] https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/trauma/about-trauma/

[11] Cited Marie-Charlotte Currier (2024: 35) ‘Entangled Traces: Materiality and Memory in Igshaan Adams’s Dust Clouds’ in Marie-Charlotte Currier (ed, with design by Cecilia Serafina) Igshaan Adams: Weerhoud (Catalogue) Wakefield, The Hepworth, Wakefield.

5 thoughts on ““You like to beautify your trauma”’. This is number 1, from a series of 6 blogs, on a day visit to see the art in exhibitions at the Hepworth in Wakefield.”