Some prompt questions are difficult to answer without making assumptions that reveal injustice with which I am in effect in collusion. To travel is an exploratory state of experience of either body and mind, but it cannot be experienced, without an assumption of a secure base from which to travel, and to which you can imagine return – a thing we might call ‘home’. This is the presumption of epic literature since The Iliad and The Odyssey. What would adventure, with purpose or for the relaxation of purpose be, without the sense that we are unlikely to be able to rest on that travel without danger to body or soul, the kinds of dangers Odysseus encounters – in which hs body could be consumed by things with only one purpose, and therefore only one eye, like a Cyclops, or persuaded into a drugged sleep or sensual submergence so profound that the body loses any other purpose than passive ones – to rest and feel pleasurable sensation that does not stop. This is so even for an Odyssean traveller like Leopold Bloom in James Joyce’s Ulysses, whose travel plans do not extend beyond his city, Dublin and take place in one day. Meanwhile his home is occupied, his Molly luxuriating in the impression on their marriage bed left by another man.

Even Ulysses in Homer faces the occupation of his home by alien forces – suitors for his wife, and thereby his kingdom of Ithaca – that he must outwit. But what if he failed, or felt that he could never challenge the forces that occupied his home and made return except in some alienating disguise impossible. This imagined scenario does not need imagining if you live in an occupied homeland, even denied the name of a country that can be claimed as ‘home’, or a possible alternative resting place denies you the asylum required in order to re-home, and lay down new roots.

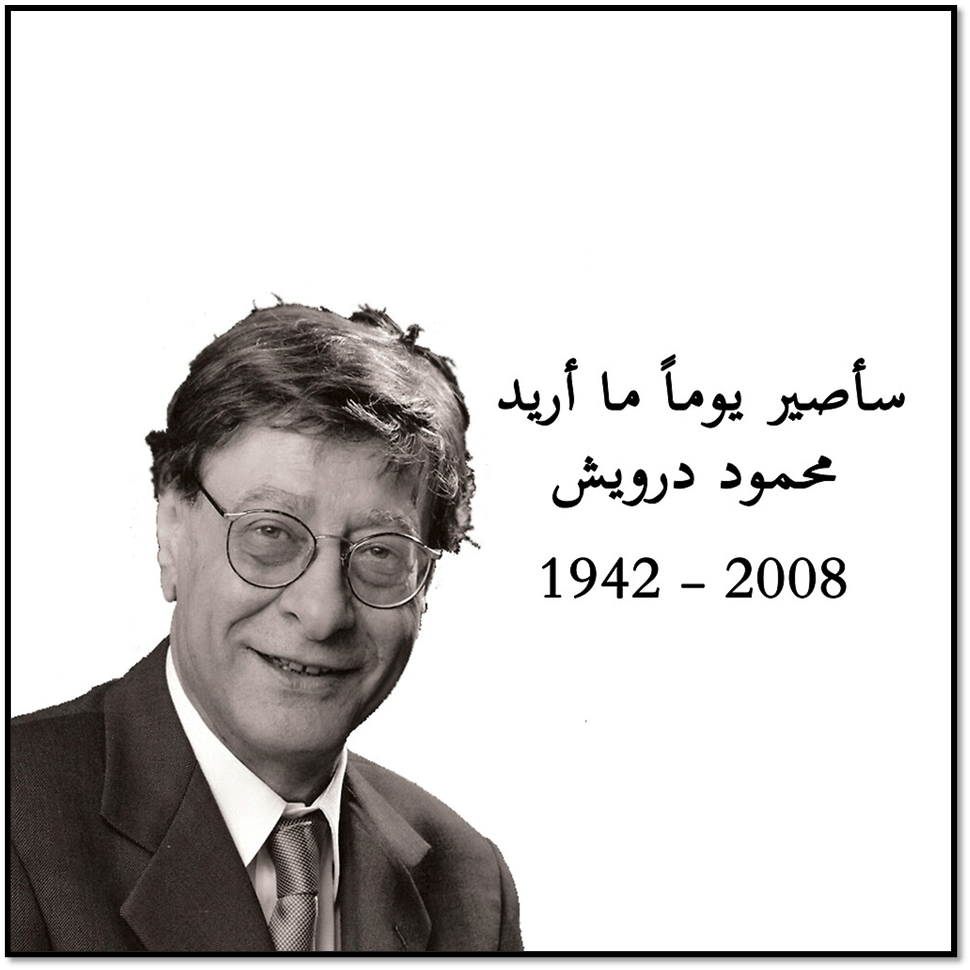

In London on a visit recently I bought the final volume of the translated poems of Mahmoud Darwish (translated from Arabic by Catherine Cobham) named A River Dies of Thirst: Diaries.It has a good preface by poet, Ruth Padel. These are poems, or Padel says the unedited thoughts that might later be poems (or alternatively work as beautiful prose-poems) in which a self-conscious poet lays bare his task – not only in the recurrence of subjects apparently unrelated but that seem to always to fall into a confused amalgam of stuff, like the manner in which we experience a future so full of uncertainty that we cannot ‘plan’ for it, either to travel through spaces or times that ought to be open to us but are barred. Padel feels his final ‘mots‘ are ‘writerly’ versions of this where planning to travel even into writing another line of a poem seems full of threat or possibility, but for him for reasons yet to explore, more full of threat that it mixes fear so intense, the threat seems supernatural yet it is not – it is that posed by Occupation. She cites this:

“The second line,” he writes (this will touch any poet’s heart in whatever language), “is the battle of the known and the unknown, when the roads are empty of signs and the possible is full of contradictions … You are like someone setting off into a forest without knowing what awaits you: an ambush, a shot, a bolt of lightning, or a woman asking you the time.” [1]

If these poems, prose-poems and of reflections on life, including plans of travel (Darwish was well-travelled because always displaced), tell us anything it is of the smug entitlement of those with a shared imagination of a homeland, supported by material ‘evidence’ in the signs and labels of language and the solid and abstract things (plans being the of the latter nature) they metamorphose into the stuff of our scaffolded identity can feel as they turn happily to this ‘prompt’ to think freely about issues where many in our world are far from free but bound. The bondage implied can be that of marginal (what used to be called sub-cultural) identity in a hegemonic culture that imposes its norms, in Gaza now with the most extreme of violence, or with our collusion or enforced (but sometimes unconscious) permission or lack of overt resistance. Darwish was never a mono-cultural poet or person. Hi Palestine was full of Jewish traditions and a deep knowledge of Hebrew writing, challenging Padel tells us, the stark vision of Zionism that saw in Palestine “a land without a people for a people without a land”, for Palestine did have a people, one that Zionism wanted us to forget – a people who knew they were now cast into a struggle both viscerally real and one only (but why say ‘only’) real in the core psychology of everyone who could inhabit Palestine peaceably, ‘a “struggle between two memories”. Darwish learned Hebrew from a Jewish teacher he revered, fell in love first of all with a Jewish young woman, but was also imprisoned by a Jewish female judge. For him, even Zionism was only a belief system masking ‘human beings’ first and foremost: ‘”I will continue to humanise the enemy. Poems take the side of love not war”.[2]

But that vision was not ever a binary one, except in the later version of Zionism, which divided the world into totally unnuanced blocks of Jews and Anti-Semites, without recourse to the fact that Jews were never the only ‘race’ labelled Semitic. What of the divided Christian tradition, what of the Druze, whom Robert Browning championed in his early highly politicised play writing with a drama called The Return of The Druses ( centered on a return to Lebanon, the chief center of the Druze populations who are otherwise still significant in modern Israel and the Palestinian territories). [3] It becomes a binary vision, only in the strain of an irritant, a tiny mosquito, that proposes to you nothing but ‘fruitless battle’ and that you know you cannot appease and disrupts the comfort of having a home to rest in: ‘There’s only one way you can bargain with it to make a truce: by changing your blood group’. And to change that is not possible, and hence the battle continues.

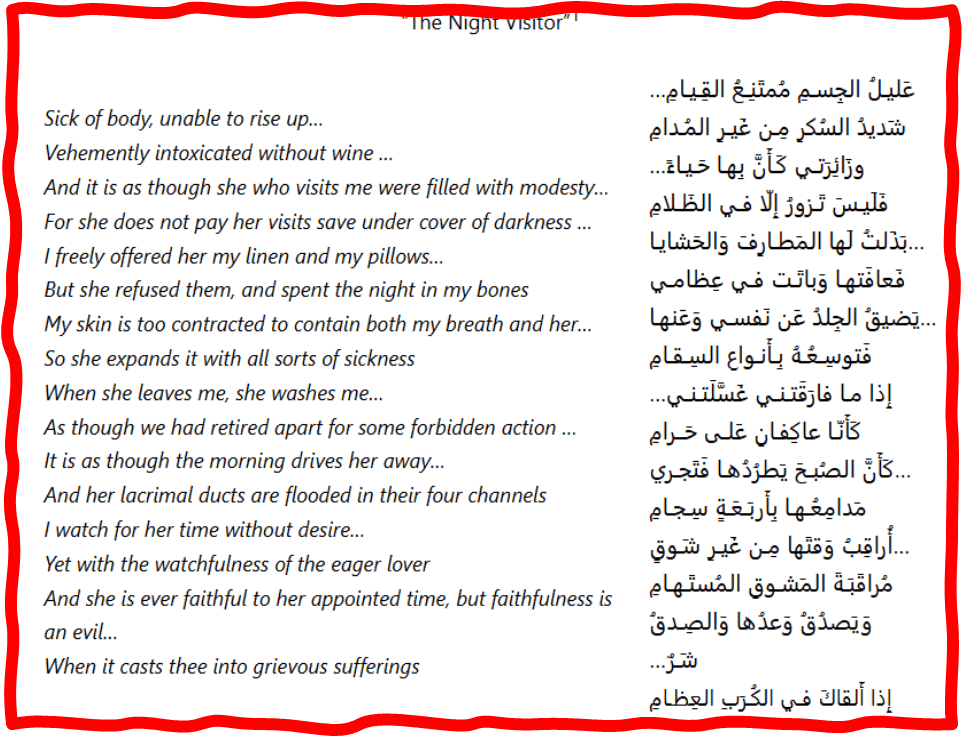

The mosquito can make no claims to be a great poem by Darwish, but it is fundamental I think, for it invokes the best known poets of Arabic history, al-Mutanabbi, who described what is thought perhaps to be malaria in the 10th century AD (use the link to see an academic use of the poem in Medical Humanities), much as Darwish does the mosquito fundamental to the aetiology of human malaria. Darwish’s use of al-Mutanabbi feels highly charge, for reasons I find it difficult to explain but it clearly, if you look at the original poem has something to do with sex / gender. Darwish says of his insect that: ‘It only visits in darkness like al-Mutanabbi’s fever’ :

The description in the parent-poem of al-Mutanabbi of the ‘fever’ that medical specialists who read it think may be malarial is feminine. The night-visitor is not only feminised throughout but her femininity is problematic in relation to the poet, almost exclusively in terms of heterosexual desire both expressed and unexpressed, experienced or merely imagined or present only in its absence. She is faithful to time but is filled with shame at the immodesty her visits at night to a man to whom she has no public relationship might suggest if seen. She acts as if they had committed secret sexual congress, whilst clearly not thus engaging. Her contradictions are matched by the poet’s – who is simultaneously demonstrating the ‘watchfulness of the eager lover’ whilst he also watches ‘for her time without desire …’. Of course, she and her actions are but an elaborated metaphor but there is such force that the woman lives inside he poet at night, straining the skin that tries to contain the expansions her interior action causes.

As I read, I wonder if we need to assume some knowledge of The Night-Visitor in order to understand why Darwish is so perturbed from the very beginning of the prose piece that he cannot name a mosquito in what he thinks the appropriate gender in Arabic language: ‘The mosquito, and I don’t know what the masculine form of the word is in Arabic, is more destructive than slander’. But why introduce gender here if it is not to indicate some depth of relationship to the earlier 10th century poem. Indeed he repeats the verbal formula about linguistic gender of nouns twice, in the same words in this English translation:

The mosquito, and I don’t know what the masculine is in Arabic, is not a metaphor, an allusion or a play on words. It’s an insect which likes your blood and can smell it from twenty miles away. [4]

Emphasising the real nature of his irritant, which al-Mutanabbi refrains from doing of his fever, which even if a feminine noun in Arabic ( I do not know) is not a ‘real’ feminine (for an account of this read this useful blog by Ibnulyemen اِبْنُ اليَمَن ). A mosquito as a living thing must have masculine and feminine form for so does the animal in popular account. Moreover, I wonder how much Darwish assumes we know of mosquito sexual life-cycles for they are fundamental to why we distinguish sex/gender in these animals. does this web-page help fill in our knowledge – it does mine:

There is more to know. Because of their need of blood in gestation, the female has the stronger ‘mouth-parts” that bite. Hence, assuming Darwish assumes we assume he knows this, it raises the question of why at all, he needs to know the masculine name for a mosquito in Arabic because, his irritation about the bloodsucking and its consequences is unnecessary. The likelihood is this insect, if real and NOT a metaphor, is feminine. Moreover, Arabic readers would understand that though gender in Arabic nouns can be problematic, when naming a living thing the noun (and associated grammatical parts like adjectives) takes the masculine form for a male, and the feminine form only if a female. More problematically, in Arabic, the female form of a real (the word is used only in relation to grammatical rules) gendered noun is created normally by adding an extension to the grammatical male default form, so that not to know the ‘masculine form’ of a word when you have the feminine noun seems counter-intuitive, for one merely releases it from its extension.

What all this suggests is that Darwish thinks sex/gender matters in this context for other reasons, which mean that we must disregard the statement that his use of the word mosquito is not partly metaphoric. He is a clever poet like that. The mosquito with its alarming attacks, resistance to elimination, diplomacy and consequent counterattacks can be no other that a reference, perhaps even allegoric to Israeli Occupation in which ‘having sucked most of your blood it starts humming again, threatening a new attack’.[4] It wipes out chances of successful and even the ‘words’ in your book, making night raids and is’ like a warplane which you don’t hear until it has hit its target: your blood’. Ans this force is a masculine force in large – an army of advanced military might, the male who intrudes on you at night.

The sex/gender confusions here are extremely fruitful in opening up the relation of history and fiction in this brief work, of the contiguity of all contradictions, including those between male and female self expression as historically, politically and socially acculturated real and fictive moments in time and experience, as well as those between the proximate and distant, security or threat. The mosquito matters because it is an insect that, however, you plan and act, you cannot escape it. It consumes you and your plans. For Darwish knowing whether he was safe in the countries once thought of as homeland was his constant preoccupation. Forced into a decision about exile, he concentrated on perfecting his poetry. When permitted to return to live In Ramallah in the West Bank, whist Darwish was visiting Beirut for a poetry reading in 2002, the Israeli army invaded and his manuscripts were lost on a raid on the offices in which he edited a literary review and his manuscripts stolen or trampled by army boots. Padel, in telling this story quotes Darwish as saying: “They wanted to give us a message that nobody’s immune, including cultural life”. (5)

Ramallah

To illustrate why a person may not to be allowed to plan travel as an entitlement has taken a long circumlocution through The mosquito but I think the excursion is worth it, for planning travel depends on the security of that to which you return. In the poem An eagle flying low, a ‘traveller in the poem’ speaks to ‘the traveller in the poem’. We do not know if this is one person or two, but both travellers feel that they neither name the distance they plan to travel nor even, as they travel name themselves. Unable to travel, they decide to ‘sing’ yet knowing they will not be heard on the two mountain tops from which sings to the other over a ‘chasm’. But like characters from a Becket play, they keep trying to second-guess their journey

'Then you ask me and I ask you:

"How much further do you have to go?"

"All the way"

"Is all the way far enough for the traveller to arrive?"

"no. but I see a fabulous eagle

circling above us, flying low!" [6]

The poem starts with the same question with which it ends and leaves us with a contradictory image of something that might be an image of liberation or threat, for warplanes when the ‘fly low’ drop bombs. The point. Never plan your journey but never stop aspiring to go far enough, whether in pursuit of a home, from which you might travel more definitively, or a perfect poem in lieu.

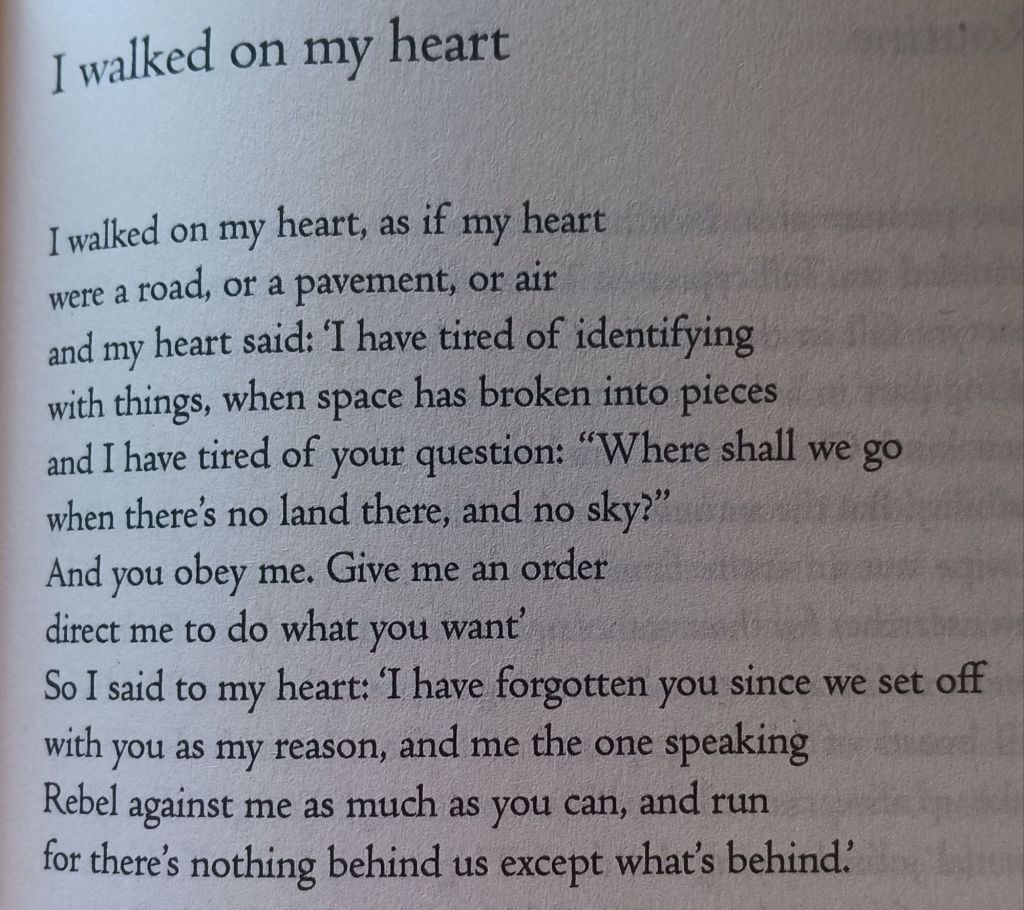

However, I find I started this confidently only to be able to travel very little further on my planned path, so instead I will after reflecting on one more poem, leave these behind and plan to read many more> i found on my shelves John Berger’s co-translation of works by him and i will order the major selection of poems in English and get to know this poet better, for I have discovered that though Darwish illustrates how entitlement to travel freely, and hence to plan for such is denied by the more powerful to those in the wake of History’s unchallenged juggernauts, thinking about all demands serious attention, from me at least, and I ought to write more fully later. Travel though is the metaphor by which we walk on hearts in I walked on my heart, and I think this is a good resting place for reflection.

Here is the poem in full:

The poem almost speaks to our prompt. Asked ‘What are your future travel plans?’, Darwish proposes that the travel he has done as used his ‘heart’ as it ‘were road, or a pavement’. His heart answers back that:

...: 'I have tired of identifying

with things, when space has broken into pieces

and I have tired of your question: "Where shall we go

when there's no land there, and no sky?"

The heart in rebellion refuse to be trod upon again though the poet says in reply to it that the heart was his reason for setting off on travel in the first place, and that though he tries to cajole the heart that to ‘rebel’ and run’ away is to forget ‘there’s nothing behind us except what’s behind.’ It is a knotty poem that seems to speak a little to the fact that we only feel entitled to travel when we know where we are going and we are sure of our feelings about setting off to that place. But the solidity of things, and wholeness of time and space are neither knowable to either heart or poet, ‘me the one speaking’. A poet cannot reassure their heart that plans to ‘go on’ together are worthwhile, all they can say is that until there is more ‘behind us’ than there is in front of us, we will travel with the poet walking on his heart, for he has no alternative. Planned travel, after all depends on a ‘home’ to which to return to that ‘behind us’. [7]

Darwish’s home village, Birwe, was ‘erased from the map’ by the Nakba. Padel cites Edward Said (Edward Said – Wikipedia) to describe the traveller-poet Darwish: ‘Darwish’s poems, said Edward Said, ‘transform the lyrics of loss into the infinitely postponed drama of return’. [8]

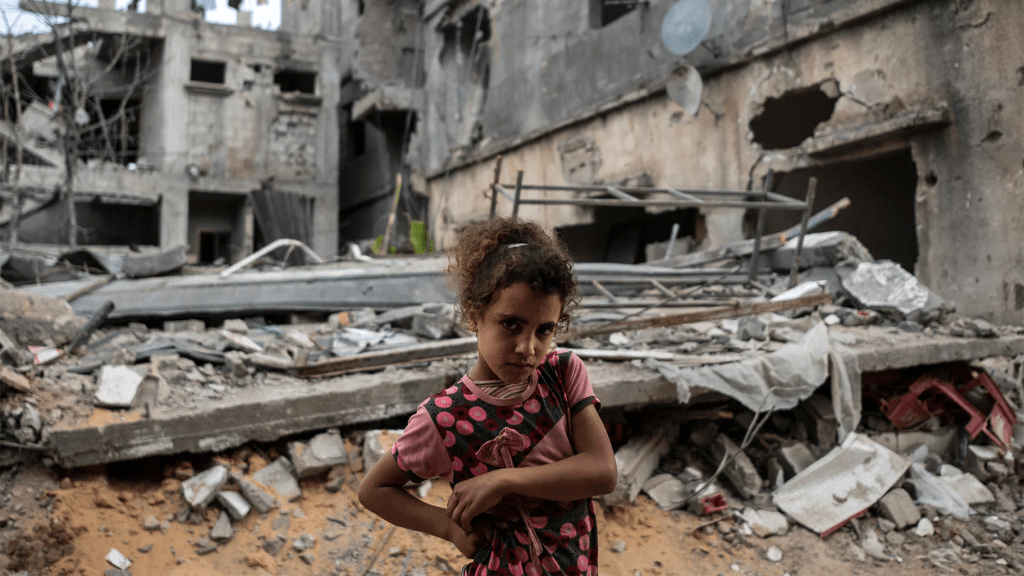

Meanwhile in my entitlement, relative but in comparison to present-day Gaza, it might as well be absolute, I plan trips to see art, theatre and film, sometimes alone and sometimes with my husband, but that is only because my heart now stays at home to be consulted, to make sense of the adventure in the light of some security. No security is absolute but how fragile it is in the world now for too many. They, the dispossessed, the occupied, the fleeing migrant or Romany traveller remain despised and manipulated, rather than understood as that which we have left behind because we thing what holds our past and future together as a cocoon around the present is our ‘home’ and the homely, the heart of things. I only plan these things not to walk on my heart but to return to it.

Gaza now. Does this girl ask herself, to where ‘do I plan to travel in the future’.

With all my love

Steven xxxxxxx

____________________________________________________________________

[1] Ruth Padel (2024: xix) ‘Preface’ in Mahmoud Darwish (translated from Arabic by Catherine Cobham) A River Dies of Thirst: Diaries, London, SAQI Books. xi – xx. First published 2009.

[2] ibid: xv

[3] For the full text – go on be one of the few to know of it – see: https://www.telelib.com/authors/B/BrowningRobert/play/returndruses/returndrusesa1s1.html

[4] ‘The mosquito’ in Mahmoud Darwish [translated from Arabic by Catherine Cobham] (2024: 12) A River Dies of Thirst: Diaries, London, SAQI Books, 12.

[5] Padel op.cit: xviiif.

[6] ‘An eagle flying low’ in Mahmoud Darwish [translated from Arabic by Catherine Cobham] (2024: 13f.) A River Dies of Thirst: Diaries, London, SAQI Books, 13f.

[7] ‘I walked on my heart’ in Mahmoud Darwish [translated from Arabic by Catherine Cobham] (2024: 17) A River Dies of Thirst: Diaries, London, SAQI Books, 17.

[8] Padel op. cit: xvii