If you could host a dinner and anyone you invite was sure to come, who would you invite?

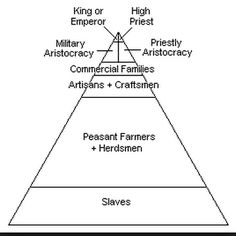

Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party (above) is an iconic image from the history of feminist art and is replete with symbolism that suggested that women could create the imagery of their own world without evoking patriarchal traditions, even of leadership. Its overall form was intended to make it the perfect symbol of respectful equality between its participants in line with the supposed notion that an equilateral triangle was the perfect idea of shared equality. The equality however is entirely one of mathematical analogy as Wikipedia’s description of its size features shows:

The table is triangular and measures 48 feet (14.63 m) on each side. There are 13 place settings on each of the table’s sides, making 39 in all. Wing I honors women from Prehistory to the Roman Empire, Wing II honors women from the beginnings of Christianity to the Reformation and Wing III from the American Revolution to feminism.

Though the aim is to honour women as makers and thinkers, with a claim to ‘primacy’ in those roles, there were expressions of concern among other feminist artists and commentators that the work’s effect contradicted its intentions. There were inequalities some suggested in the quality of the work between sections, women were represented only as Chicago saw them and without an attempt to see them aided by their own self-perceptions and that an idea of womanhood reduced the participants to a simple set of biological markers, in that many ‘of the plates feature a butterfly- or flower-like sculpture representing a vulva‘. It is likely that this commonality of symbolism was based on the belief that this empowered the work to contradict the ubiquity of phallic imagery in patriarchal art. Here is Wikipedia’s summary of some of the push back from fellow feminists that Chicago received and which for a time to retreat from the public stage as an artist.

Maureen Mullarkey also criticized the work, calling it preachy and untrue to the women it claims to represent. She especially disagreed with the sentiment that she labels “turn ’em upside down and they all look alike”, an essentializing of all women that does not respect the feminist cause. Mullarkey also called the hierarchical aspect of the work into question, claiming that Chicago took advantage of her female volunteers.

Mullarkey focused on several particular plates in her critique of the work, specifically Emily Dickinson, Virginia Woolf, and Georgia O’Keeffe, using these women as examples of why Chicago’s work was disrespectful to the women it depicts. She states that Dickinson’s “multi-tiered pink lace crotch” was opposite the woman that it was meant to symbolize because of Dickinson’s extreme privacy. Woolf’s inclusion ignores her frustration at the public’s curiosity about the sex of writers, and O’Keeffe had similar thoughts, denying that her work had any sexed or sexual meaning.

The Dinner Party was satirized by artist Maria Manhattan, whose counter-exhibit The Box Lunch at a SoHo gallery was billed as “a major art event honoring 39 women of dubious distinction”, and ran in November and December 1980.

In response to The Dinner Party being a collaborative work, Amelia Jones makes note that “Chicago never made exorbitant claims for the ‘collaborative’ or nonhierarchical nature of the project. She has insisted that it was never conceived or presented as a ‘collaborative’ project as this notion is generally understood … The Dinner Party project, she insisted throughout, was cooperative, not collaborative, in the sense that it involved a clear hierarchy but cooperative effort to ensure its successful completion.”

There are other elements of critique here that matter. If there was some degree of ‘biological essentialism’ (reduction of womanhood to selective biological parts) that minimised the specific contribution of the great women, real and mythical, that it represented, there was also a stress on only women already distinguished by patriarchy and the power structures of the status quo. Merely including Sojourner Truth did not truly hold up against this critique, for there was, it was thought some degree of tokenism in lauding individual breakthrough women rather the cause of all the women they represented, that were often missing from the white middle-class feminist account. What, implied Manhattan, of ‘women of dubious distinction’ or those excluded from distinction, who were likely to open a ‘lunch box’ at work than visit a bourgeois dinner-party. .

I have never seen The Dinner Party but one reason for that is that the very term ‘dinner-party’ is mainly associated for me with a middle-class ritual in which the host exerted control of seating, the pattern of conversation (When I was at University College London studying English) Dr. Keith Walker, a friend then, reported a story told by Stephen Spender (who taught there) of how Virginia Woolf used hand signals to conduct the lay equivalent of sacra conversatione at her dinner-parties, using a downward spiral of her hand to indicate the pattern of how the present discussion should condescend to its conclusive end).

Whilst we think about Virginia Woolf, it is usefully to reread Chapter 17 of To The Lighthouse, in which a dinner party of enormous preparation in the effort of commanding servants (including the tiresome reminders to the Cook about the length of time Boeuf en Daube requires for the marination of the meat. Mrs Ramsey, Like Clarissa in Mrs Dalloway, though there about an evening dress party, feels here life to be one of waste that is somewhat redeemed by a life manifest in perfectly invisible control of a social occasion. Her thought turns to the fact her life is given up to the ‘sterility of men’, like her husband but also the former mariner, William Bankes, who might be fulfilling his function better dead at the bottom of the sea.

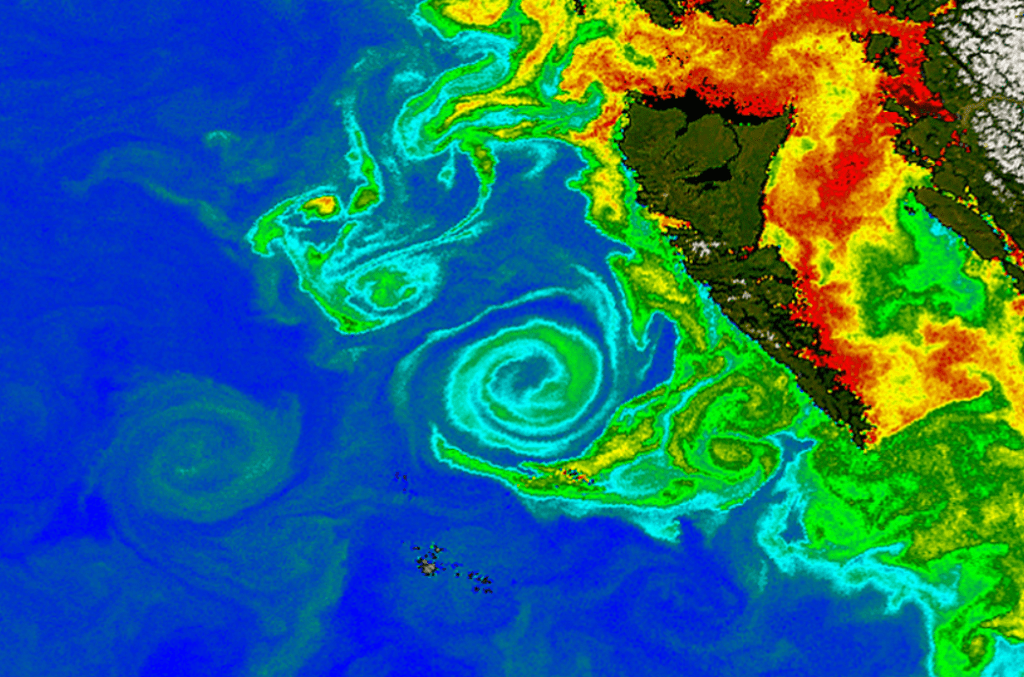

But what have I done with my life? thought Mrs. Ramsay, taking her place at the head of the table, and looking at all the plates making white circles on it. “William, sit by me,” she said. “Lily,” she said, wearily, “over there.” They had that–Paul Rayley and Minta Doyle–she, only this–an infinitely long table and plates and knives. At the far end was her husband, sitting down, all in a heap, frowning. What at? She did not know. She did not mind. She could not understand how she had ever felt any emotion or affection for him. She had a sense of being past everything, through everything, out of everything, as she helped the soup, as if there was an eddy–there– and one could be in it, or one could be out of it, and she was out of it. It’s all come to an end, she thought, while they came in one after another, Charles Tansley–“Sit there, please,” she said–Augustus Carmichael–and sat down. And meanwhile she waited, passively, for some one to answer her, for something to happen. But this is not a thing, she thought, ladling out soup, that one says.

Virginia Woolf ‘To The Lighthouse’, Chapter 17 (excerpt)

Raising her eyebrows at the discrepancy–that was what she was thinking, this was what she was doing–ladling out soup–she felt, more and more strongly, outside that eddy; or as if a shade had fallen, and, robbed of colour, she saw things truly. … And so then, she concluded, addressing herself by bending silently in his direction to William Bankes–poor man! who had no wife, and no children and dined alone in lodgings except for tonight; and in pity for him, life being now strong enough to bear her on again, she began all this business, as a sailor not without weariness sees the wind fill his sail and yet hardly wants to be off again and thinks how, had the ship sunk, he would have whirled round and round and found rest on the floor of the sea.

But as she thinks of Bankes whiling round and round (that spiral again) down to the bottom of the sea, she knows she must control similar eddies in the motion of the fluid dynamics of her party. A perfect host must watch and control of such dynamics, whilst aware that this was a kind of futile exertion of energy and time: ‘as if there was an eddy–there– and one could be in it, or one could be out of it, and she was out of it’. All she can do, as it were, is arrange the seating on the Titanic and try to keep her particular ship afloat. The more she sees herself functioning merely as the one ladling the soup the more ‘outside the eddy’ she feels.

Why, be in the eddy, however, if you cannot control it. You might end up as dead as Bankes swirled down by natural motion. Mrs Ramsey is continually on the edge of attempting to control that she can’t, whilst serving men who can’t either, though the party do get to the Lighthouse in the end.

And control is the stuff of dinner-parties Woolf saw. Yet here she sits at Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party, locked in similitude as an open vulva.

And, in the end, I will stick with not wanting to see Chicago’s work, now static in the Brooklyn Museum, honouring a phase of feminism. I cannot defend myself from another person’s belief that this is about the ‘sterility of men’ facing great female art and its iconic motifs. We are all more complexly determined than we like to think. But what upsets me about the very idea of the work is that it is a work controlled by measured distances – of women on a table from each other controlled by an idea of a dinner-part that I can invite anyone I like to, and they must come, for death has rendered them passive.

I imagine what it must be like to be at that dead table with my place mat keeping separate and boundaried from others, staring across the vast empty space but for writing on the floor to the other sides of the enclosed triangle. It is not a symbol of equality but enclosure and enclosure in a motionless symbol of one’s achievement I have not chosen or had part in myself. In doing the work, which Chicago called cooperative, she had male and female co-workers and the criticism was not about that but that she allowed female assistants o more input into the work than anyone else – these others were there to succumb to her control – a control eluding Clarissa Dalloway and Mrs Ramsey. That is because, if a work is cooperative (and even if it is not collaborative), it surely ought to involve cooperators in more than seeing themselves at the bottom of a hierarchy(another controlling triangle). Remember the work is defended in these terms as involving: ‘a clear hierarchy but cooperative effort to ensure its successful completion’. For the triangle is more a masculine system of patriarchal relations than it is anything else, where others just help me get my idea to ‘successful completion’.

Watch out for that Eddy though. For he, she ot they come for those still controlled by labels, and will suck down whoever aspires to that kind of control and regulation if they haven’t, as the saying goes, ‘the balls’ to break free. The point is balls have nothing to do with control really. Biology is not the determinant of power and status. Social encoding is.

Pass me my lunch-box, comrade and have yours back, for I have put a treat into it. We can share the difference for we are close: you, you, you …. and you (pointing at themselves) not set apart around a bourgeois table.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx