What are your daily habits?

I took up blogging in response to a course I took with The Open University in 2015 called Technology-enhanced learning as part of a MA in Open and Distance Learning.

Sceptical at first, I persevered with its encouragement to use available technologies, even ones not primarily geared to that end, such as social media platforms, like the then Twitter.

Blogging too was an experience the course demanded rather than recommended as a digital technology one had to evidence as being used as a tool for personal teaching and learning, separately or both combined. I used it in my teaching to encourage learners to wish to write rather than to do by command and under threat, as it so often seems to learners (and to me as a learner) of immediate assessment of their knowledge and skills, often by a system guided by values quite alien to them.

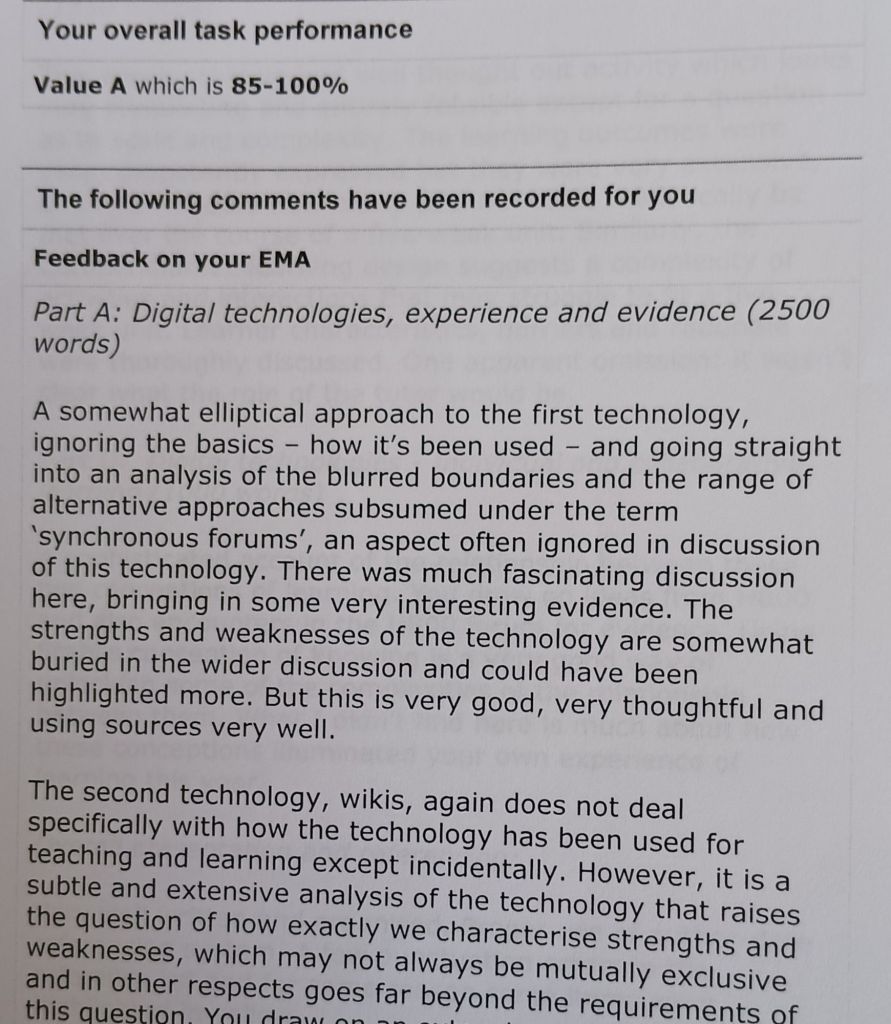

Blogging felt free in comparison to the idea of essay writing. Strangely enough, though, I did well in this particular module and was awarded a high mark. The examiners felt they had to mention, however, that I had a ‘somewhat elliptical approach …, ignoring the basics’. I gleamed at that because it, to me, showed I valued my own learning over the conventions valued by the system.

The evidence that I ain’t just making it up

I stayed with blogging as I continued teaching and my own learning, using it in retirement as a means of continuing the lifelong learning that had become habitual through my life since that course but in truth before tbe course too, though not then using digital tools. My personal learning though was still dogged, as my learning may always be, by the habits over-learned in an academic career, like the habit of referencing evidence that is not a necessity of learning addressed to judges who are not by definition committed to conventional forms of appraising learning outcomes in anyone else. I think other aspects of the conventional academic mode get dropped by retirees more easily – like the retail of the ‘basics’ in relation to a task based on answering a question. Suddenly, the blog seemed made for an ‘elliptical approach’, skirting the issues you only tell the reader, knowing that they know about them already, so that they know you know it too. The paradoxes of teaching assessment! The aim of such readers is to tick boxes on a formal assessment

INSTEAD, a blog can dive straight into what defines one’s own particular interest, beyond those basics. As the assessment of my performance in the University course cited above went on to say, the ‘subtle and extensive analysis’ I aimed for was such that it intended to go ‘far beyond the requirements of this question’. That is a perfect way for an academic to express distaste for a learner’s style of discourse in a way you are not allowed to express by marking the answer down a scale in the terms of the formal assessment!

On reflection, this is how I use blogging, whether in response to a question or not – in reviews or reflections on my reading, watching and hearing cinema or theatre or commenting on some book within my interests, often on mental health. Of course any oft-repeated action can become over-learned, the first step to being processed subconsciously. Such functions of over-learned behaviour, like driving, usually become things we do less consciously than we do as an apprentice or novice on the behaviour; where the skills are still being absorbed as we grow to need them. In subconscious over-learning, fuller consciousness of what we are doing can be increased by a stressful event, such as an alert that an accident might happen whilst driving.

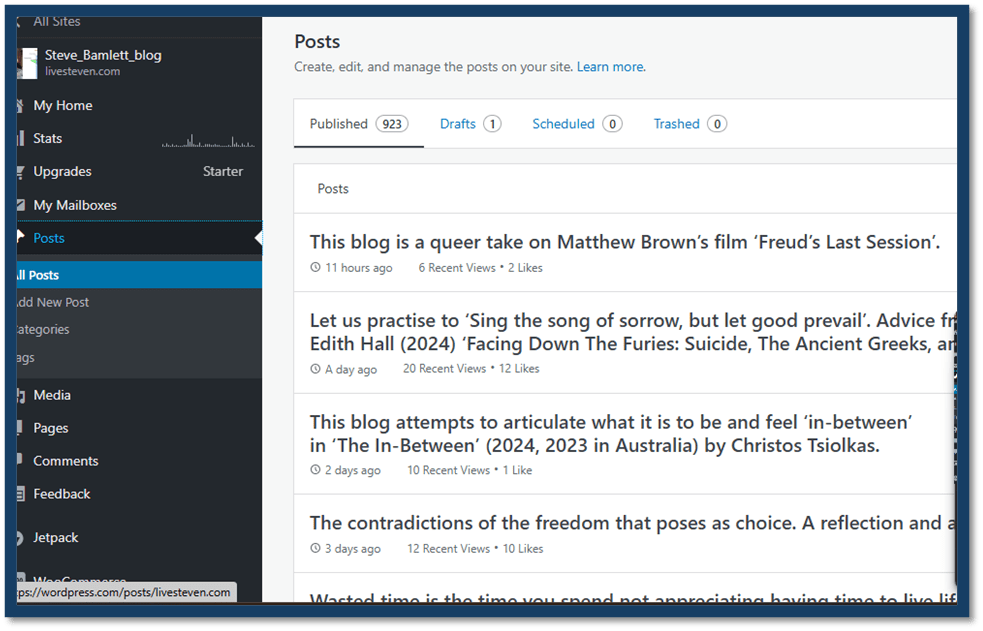

Blogging has indeed becomes a habit (witness the statistics above from the WordPress account I used after my Open University account was censored and my access to it cut for critiquing ‘academic’ practices in that institution) but not one without stress. It is a habit for me in that I turn to do it daily, often without thinking. At the moment, with this blog, I will have completed my longest run of daily blogs to date (214 days). And as a habit, it can show the effects of being habitual – for instance, a rota of repeated subjects, conventional techniques of analysis and styles, or even signs of hasty and shallow thinking. That is a danger, I think, as great as writing to the demands of a convention in the academic or any other world. I can only hope that, if motivated by personal learning, it will demonstrate that though the blog is an expected habit, its content will be forced onto material that it sees anew, or at least, not as thinly as it would have seen the experience recounted otherwise. And I think that is because the act of being forced to notice significance in something that you do daily itself causes stress and refreshes the more conscious processes of thinking alerted to its need to perform appropriately.

Today I was unclear about whether I was motivated to write about any of my experience – inevitably routinised as it is by retirement. I read habitually more than I blog and I suppose that is my primary daily habit. I had, moreover, finished my latest book from my reading pile but I wasn’t that keen to write about it. Today, not sure what else I could do, I have decided, despite my lack of pre-motivation, to do so, though without my usual note-taking scan. Will I, in forcing myself thus, find that my habitual methods of reading will convert my feeling that I had nothing worthwhile to say about the book, in my eyes, to something more urgent. The book has been awaiting reading for sometime in my ‘reading pile’. It is a work by Salman Rushdie.

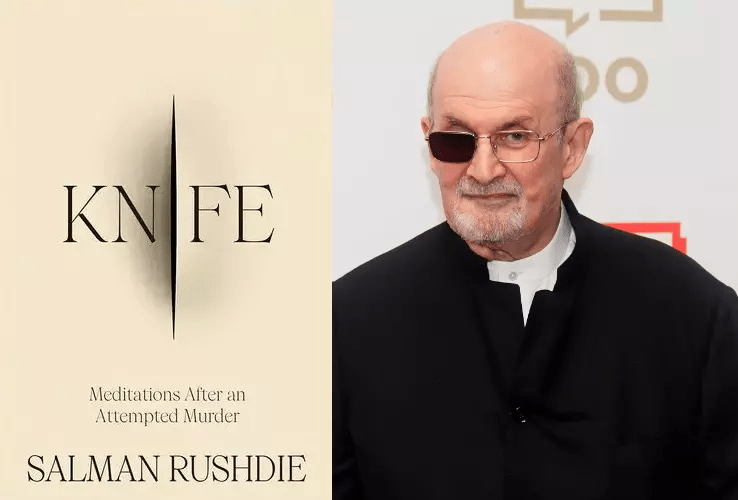

It is his memoir, Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder; detailing the knife-attack upon him on August 12, 2022 and its aftermath in two parts with obvious messages in their subtitles:

- PART ONE: The Angel of Death

- PART TWO: The Angel of Life.

I read it because (well!) I read all of the time AS A HABIT and blog only on those books that make me feel I can learn yet more about them by doing so. In Rushdie’s book, I thought everything that needed saying had already been said by him. There was no opening, I thought after finishing it, that I could see to re-read and reflect further from my point of view. ‘Forcing a blog out of this book would be hard, I thought. How, after all, do you write about a violent incident that was intended to do what was likely to happen after this event, Rushdie’s death. He lived as the two subtitles show if you had not known it already, but with some consequence, including the total loss of one eye, shown below in the permanent eye-patch in his spectacles.

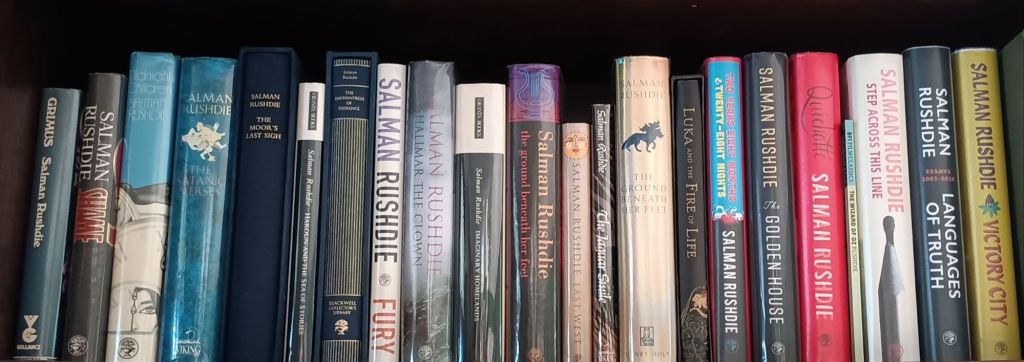

My own approach to writing semi-voluntarily on the book will be not so much to comment on it (although I will at the end if I get that far) as to show how the events that lay in its background criss-crossed my path, fo4 itbis book dependent on Rushdie’s role in well-known public events. I was not new to Rushdie as my collection below shows, though I slimmed down my collection recently, so that most of it, if not all, fits on one bookshelf currently to the left of me. Here is the shelf:

I did not read Midnight’s Children on its publication. At that point, I was not a keen reader of modern novels at all, preferring the literary canon of texts I was teaching at the time, at The Roehampton Institute, now a university in its own right. In fact, the first novel I read of Rushdie’s was The Satanic Verses in 1988, before much fuss had been made of it because my illegal husband, it was still then illegal to have a husband if you were a man, bought it for me. Indeed, largely, it was received as a relative failure by critics not keen on his narrative freedom and baroque style, often referred to as ‘magic realism’. I liked it but not as much as Shame, which was my first taste of Rushdie’s stunning grasp of historical epic like that in Midnight’s Children.

My favourite novels of his, ever afterwards were those that combined the romantic fable with the magic in a varied prose: The Moor’s Last Sigh, Shalimar the Clown (which taught me about Kashmir) and The Ground Beneath Her Feet (his magical Orpheus myth novel) and, of course, Midnight’s Children, when I eventually read it. I loved his first memoir (in the third person, Joseph Anton: A Memoir ) despite its insistence on moulding himself in part from past reading heroes, Joseph Conrad and Anton Chekhov. Other novels still leave me cold, even Victory City, his last, of which Rushdie talks about the promotion during the stoty of Knife. Victory City, he says thrre, is a ‘novel about a mysterious and enigmatic College’ based itself on the ‘mysterious and enigmatic microcosms’ represented in Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain and Franz Kafka’s The Castle. [1] In passing I ought to say that, rightly or wrongly, Rushdie’s referencing of great antecedents makes me shudder when I read it, in Quichotte especially where the aim is the great originator of the fabulous novel, Cervantes; the novel, that is, of serial fables.You sense the longing-to-be-a-great-man-of-the-novel (even its ‘progenitor) syndrome here imposing on you too closely and without the irony in his best work – in the artist in The Ground Beneath Her Feet for instance. That novel took Orpheus as its model. I loved that and bought a publicity poster (see it photographed behind the guest room clothes-hangers below).

But it is the The Satanic Verses we need to talk in consudering Knife: that novel exploded into public life after I read it, in 1989, when after mass demonstrations through Britain, the voice of Muslims was backed by British Labour politicians condemning Rushdie for his bias against Islam (and attempting to maintain – for Labour at least with its history of racism in the 1960s and 1970s – an uneasy alliance with Muslim members and Labour voters in Bradford (where one burning of the book occurred) and large conurbations with large Muslim populations like Leicester.

The claim of bias against Islam, made against Rushdie, is still being disputed by him in Knife. There, he locates the kind of religious satire he traded in as part of a wider literary aim and not exclusively against Islam. He cites his attacks on Hindu extreme belief in Midnight’s Children as evidence. His satire, he suggests, is like that prompting the 2015 shootings at Charlie Hebdo in France, one element picked out from a more general belief in the need to limit the supposed right of religion to enforce belief about conduct and speech upon others in the firm of blasphemy charges; against, that is, the pretensions of all religions to control the shape and content of private and public lives and public talk. He hates, he says in Knife, that adults should need ‘commandments, popes, or god-men of any sort to hand down morals’ or take up a religion tbat is in truth ‘politicized ideology’.[2] As Wikipedia puts it, this becomes important in his historical career as a public man, known as Salman Rushdie, because:

In mid-February 1989, following the violent riot against the book in Pakistan, the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, then Supreme Leader of Iran and a Shiite scholar, issued a fatwa calling for the death of Rushdie and his publishers,[18] and called for Muslims to point him out to those who can kill him if they cannot themselves. [3]

Although, later Iranian leaders dropped the fatwa as a demand, many Muslims knew that a fatwa, being a holy pronouncement, an eternal contract with God (and hence not to be lightly used), can never in effect be rescinded, and in that interpretation of religious law lay the seeds of Rushdie’s meeting with the knife-carrying Mr A. Mr A was originally in Rushdie’s mind Ass or Assassin as he sought names to call his would-be murderer in his book. He plumped for one with enough respect in it, even for his own asssilznt, to bear imaginary conversation therewith that is in the book. For Mr A, the fatwa still lived, though he himself Rushdie knew had read hardly more than a sentence or two of The Satanic Verses.

Rushdie entered my life then clothed in my own contradictions. I met my now husband in Leicester where together we spanned left and peace-anarchist political affiliation (the latter being where Geoff the stood writing on LGBT issues in Peace News and running a helpline for LGBT people called Gayline). Both of us had links with Muslim origin populations: both of us valued them and loved friends who thus identified, none of which though fitted the stereotypes used by the white press to condemn those against Rushdie’s insult to an already deeply insulted population from a position like Rushdie’s of relative class privilege and status, great enough to be protected by the Thatcher Government with high security). For me the, the issue was not an easy one. I am an atheist, hated the rights to censorship that condemn voices from other communities, as in the use of Christian blasphemy laws against Gay News, as much as Rushdie did but felt pain at the means used to make condemnation of minority or marginalised communities a matter if ‘free speech’, as if it were equally free to other than entitled, largely male and white, people such as those who supported Rushdie without reading the book any further than did some of his detractors.

Rushdie in Knife still feels The Satanic Verses was disrespected by those like myself embarrassed by the contradictions I speak of above. For myself, I still remember this book as more of a slog than others and more unrewarding after that slog. He still hurts at the way people turned on him for reasons that were alive in me, his belief in his own caste, class privileges and status and RIGHT to respect and says so in Knife. But try as I might I can’t help but feel these issues resurrected in this book. There is something intensely moving that Rushdie even attempted to describe himself in the immediate aftermath of his knifing, using the same semi-satiric, and certainly comic, methods of conveying how what he felt then and now contrasted with the pain and undescribable feelings he had as he faced likely extinction. He decribes himself as amidst:

a group of people surrounding me, arching over me, all shouting at the same time. A rackety dome of human beings, enclosing my prone form. A cloche, in food-world terminology. As if I were a main course on a platter – served bloody, saignant – and they were keeping me warm – keeping, so to speak, the lid on me. [4}

How are we to read this. The writing is full of associations. One is of the picture the Christian icon of the Deposition. The elements of their iconology – the arching bodies of a group over the body beyond suffering, even when the shoutiness is internalised as in Rembrandt, the icon is noisy: ‘a rackety dome’ over and ‘enclosing’ (it is after all an icon of the entombment of the body) are all there.

But are the elements of the Deposition iconology there to be themselves undermined, buried or ‘deposed’ by the humorous contrast with the image of tjhe cloche covering a serving of a meat course, served in the manner of French cuisine and with the heightened fine-dining terms from French, saignant (bloody).

The mixed-up genres of the picture created by Rushdie’s prose are deliberate and typical of him. They mixed-upness confuses the senses and the proprieties. Shoutiness at a dinner of amiable guests is unlike the shoutiness of grief and the immediate moment where trauma is lain down into its later painful silences, but they are both focused simultaneously in our understanding. From the point of view of the bloody body consumed (of beef) they would look like a little of the picture I get from this prose. Lots of reasons can be adduced for writing like this: it forces us to see and experience the shock of not knowing how to respond or the fear of responding inappropriately wonderfully. However, also makes us see the extremes of feeling involved as Rushdie become the cynosure of all eyes as a public figure, where the number of Rushdies massively proliferate in different people’s eyes. Writers must attend conferences if they are to see their products and Rushdie was willingly to go to this conference because it would pay for new air conditioning, as he tells us in Knife, in his home with his wife Eliza. But in the imagery of this passage there is a focus on the high ‘status’ or specialness of the thing focused on – the meat ‘done’ to a notion of refined perfection, disguising its visceral being under convention, as food so often does, as well as the man dressed to be killed.

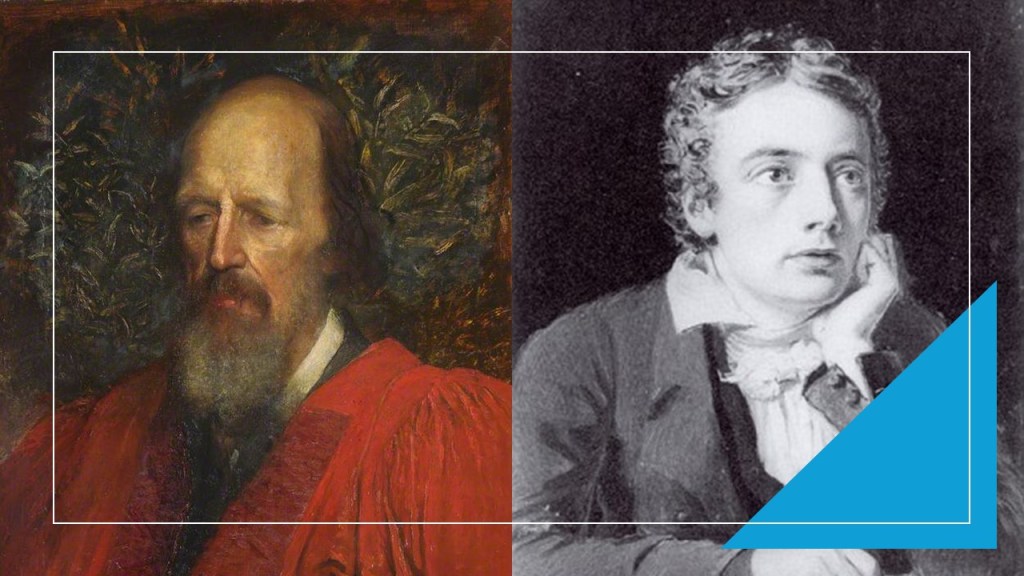

There is in Rushdie, embedded into his ambivalence about being seen in public, still that longing to be seen as in some height of worldly social status, like Tennyson’s Simeon Stylites on his pillar above his audience. Of course, he ironises the reference with humorous contrasts, but the figure in his autobiographical writing who is Rushdie or Joseph Anton must somewhere have the mythical status of the Christ, or, failing that, the allure (more comical when you see it thus but still very moving!) of a fine dish at an elegant dinner-party. This is so when he marks the inappropriateness of a dying man thinking of the material world of keys, passport and clothes – for the worldly, as interpreted through images of power and status is the only status as a MATERIALIST WORLD SEES IT. It is, after all, perhaps, all the atheist has of worlds on offer. When the crowd around him proposes to cut his clothes off to help with access to his wounds, Rushdie records: “Oh, I thought, my nice Ralph Lauren suit‘. [5]

Of course, we must think: ‘how silly of a man about to lose his life to think instead of the loss of signs of material status’. The author wants us to see that rum contradiction in human thinking. However, there are other nuances. These are resurrected later, when he revisits the scene with his wife, and stands on the stage as he did in the event. This is how he phrases it, as he returns again to a different kind of enclosure and closure, lighter than a cloche or a dome of crowded heads:

A circle had been closed, and I was doing what I hoped. (…) I stood where I almost had been killed, wearing , I have to tell you, my New Ralph Lauren suit, and I felt … whole.[6]

What is the status and tone of the verb ‘have to tell you’ in that last sentence? Is Rushdie laughing at status, or himself still concerned to manifest it amidst the seeking of ‘wholeness’, or is he showing the necessary compulsion, he sees ingrained in him of the NEED to be seen, the need to be distinguished amongst other people and his status acknowledged. No-one, of course, is immune from such longings. Few can write about themselves though with such perfect candour of irony or of the deeper truth deeper than the irony that human beings can ONLY be what they make of themselves in the EYES of others. If that is neoliberal thinking, I think Rushdie accepts that. And therein lies my continuing contradiction with him, alongside massive adoration and loving of his best writing.

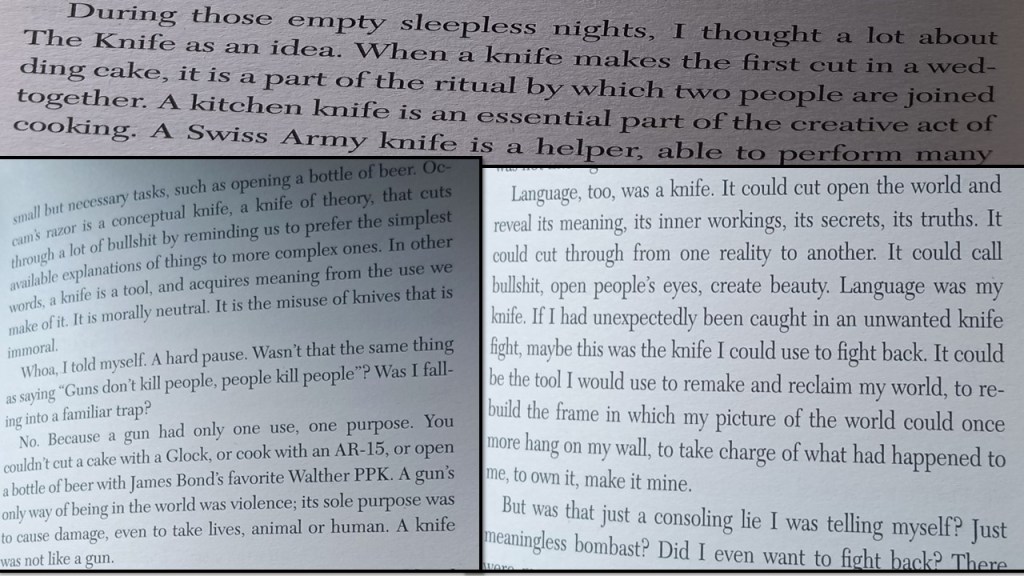

As I write, I feel I have written myself into greater learning, by my standards at least, about why Rushdie matters, but I will not now turn this into a review. This is not a book needing review. The critics who say Knife can lose pace, and fail to hold interest as well in parts, are right as they are of more of some of his less good novels, even those for children, which can be tiresome. However, at its best, he is on fire in this book like his best novels – he, as it were, ‘cuts the mustard’. And, as I say that I remember the book’s title and its telling and beautifully composed hymnal to the common material object we call a knife, for the meaning of himself is bound up in that passage, which is too long to type, so here is a photograph of pages 84 to 85 where it appears.

Knives are very basic implements, but the use of knives by human beings, even as metaphors or symbols (as a word), raises them to literary, ritual or greater significance, as well as sometimes lowers them into the most visceral of ways of delving into the viscera of bodies, human or animals. In the case of ritual killing, think of Iphigenia in Aulis, by Euripides, it is both at the same time as religion domains of thought nudge into hints of incestuous rape of a very young daughter by a tyrannical father.

Knives in cooking, in the ritual cutting of a wedding cake 🎂, and in crafting, foods or other material things, are different, whilst in the realm of meaning as part of a ‘creative act’, though they may be similar or the same in appearance and material reality. The word ‘cut’ has the same poly-valence as a word. As a weapon,it is fearsome, though it too can be used with different meanings. As a tool of ritual murder of an infidel by Shiite Fatwa, it lies at the centre of a contest of meaning. This is a contest into which Rushdie was thrown in 1989, and its consequences rippled until the formed a tsunami of violence in one man’s intentions, unnoticeable to those who claim to understand how to maintain the security of controversial authors.

The bag Mr A brought to the conference in search of Rushdie contained a ‘selection of knives’; Rushdie treats the bag with the embarrassment and perplexity of ignorance about how and why this happened, evoking humour too, though I see him here constructing Mr A here as if he was an artist, as De Quincey does of real murderers in his On Murder Considered As One of the Fine Arts:

That was decidedly odd. Risky enough to bring one knife into an auditorium. … Was he not concerned with a bag search? And how many knives? Had he planned to use more than one? Or had he found it hard to choose which one to use? … Did he think he might pass them out to the audience and invite them to join in? I had no answers to these questions. [7]

And knives are constantly being claimed as the stuff of art in this volume, whether n Polanski’s films, Phillip Pullman’s fables and Kafka’s The Trial. Rushdies says a knife was the genesis of Shalimar the Clown; ‘the image of a dead man lying on the ground while a second man, his assassin, stood over him holding a bloodied knife’. [ ]

Having found what I have found in this book, have I cut through, as with the knife of a more critically reflective mind, the rind of my habitual reading of an author’s books that it has become a habit in me to read to find its living heart snd open it up. If so, I have learned something. But one thing rankled. My metaphor here, taken from Rushdie and expanded, characterises critical reading too as a kind of violence to an author. Is hard-nosed critique therefore, illegitimate and inappropriate? Some writers think so. They remind us that writers are human too and bleed as we do. Keats never stopped reminding reviewers of this. There are elements of this special pleading in this book, but there is also a sense in it that writers may and should expect their writing to be examined forensically, its heart and soul exposed to sight.

Some people critique Rushdie’s style, indeed sometimes that of any literary writer, as having pretensions in its uses of highly charged library language and tropes. However, is that really a good charge to make against a literary fiction writer. I think not. Literature has a very basic pretension – that of being a kind of writing that endures. Even writers who claim not to write for posterity but as a necessity of their present being (Jenni Fagan is a good example) still aim to write in ways that lift language out of its common and contemporary usages to a realm common across space and time, if not eternal. If you want this you can only do it by practising writing as a means of ritualising language and the function of stories. People often claim to hate art that is pretentious. Bug if art does not start by pretending to something outside time and space, it probably isn’t worth being named ART.

And Rushdie is art. The sentence I quoted earlier is art. Read it again:

I could see as through a glass darkly. I could hear, indistinctly. There was a lot of noise. I was was awarea group of people surrounding me, arching over me, all shouting at the same time. A rackety dome of human beings, enclosing my prone form. A cloche, in food-world terminology. As if I were a main course on a platter – served bloody, saignant – and they were keeping me warm – keeping, so to speak, the lid on me. [4, repeated & extended}

You will see in this extended version of the quotation it is prefaced by that phrase from I Corinthians 12 that has been exploited by art since that of Byzantium and Rome to show the difference between the sight of the Divine and the human eye. The human one works through ‘dark’ metaphor and imagery not ‘face to face’. Rushdie even tells you he had done this in his penultimate chapter, in case you missed it, where he returns to this chapter for its wisdom about matured vision and the consideration of partial blindness (see around page 184), such as his after the attack. But I insist above, and still feel that this paragraph however laced with humour (for that is Rushdie’s style, is about the pretension to high art. And this pretension IS A NECESSITY of art not a failing, the word needs detoxification from bourgeois values.

Only art will engage with the resonance of the creation of artist and audience understood as a group of living breathing beings, forming an ark of enclosure round the cold body of work 9the ‘prone form’ like Christ’s) of a writer, who one day must die, for the purpose of ‘keeping it warm’. For that is what readers do when the art matters more even than the artist: they offer the pulse of their warm blood and the breath of their bodies to make the rhythms and sounds of verse or magic prose. Take Keats again. In the following short snatch of verse, he embodies his writing as a ‘living hand’ (it is common or was to call writing one’s ‘hand’) that when cold and dead must be revived by the reader who loves, and breathes to becomes its fleshly body. It is the definition of drawn or written art.

This living hand,now warm and capable

Of earnest grasping,would, if it were cold

And in the icy silence of the tomb,

So haunt thy days and chill thy dreaming nights

That thou would wish thine own heart dry of blood

So in my veins red life might stream again,

And thou be conscience-calm’d – see here it is–

I hold it towards you. [9]

There that is today’s blog done. It was forced. It may itself be deathly in its pretension but it is not meant to be at the end, for I feel as if ‘I myself with (this) have grown’ as Tennyson did with the more worthwhile lyrics of In Memoriam.

For I myself with these have grown

To something greater than before;

Which makes appear the songs I made

As echoes out of weaker times,

As half but idle brawling rhymes,

The sport of random sun and shade. [10]

Except for me, being no poet or novelist, it is not the ‘songs’ I made that seem weaker and idle but the thoughts I had that had failed to be energised by reading Rushdie out of habit rather than living interest. Now I feel the life in his words revived and I expect that to be the case when, as must occur but is ot wished, we lose him in his ‘living hand’. So why not keep on blogging as a habit, even when the habit palls. And we must do so because the signs of near death in oneself can be misread. We need not always get lost in the mire of the everyday where ‘to go back would be as tedious as going on. Just go on! Please! I will try too

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxx

_______________________________________________________________________

[1] Salman Rushdie (2024: 173) Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder London, Jonathan Cape

[2] ibid 183f.

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Satanic_Verses

[4] Rushdie 2024, op.cit: 16f.

[5] ibid: 17

[6] ibid: 209 (…) indicates my omission

[7] ibid: 194f.

[8] ibid: 20 – 22

[9] John Keats ‘This living hand’ available at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/50375/this-living-hand-now-warm-and-capable

[10] From the Epilogue to In Memoriam, see https://kalliope.org/en/text/tennyson20020226132