What’s your favorite thing about yourself?

My least favoured word in the world is favourite, the Queen of a world of words dominated by a lack of impersonal values. In such a world, people can only be asked what they 👍 like and 👎don’t like, as if the world were entirely contained by moments of personal pleasure or displeasure, empty of choices guided otherwise; by reason, ethics or principle. We are in the middle of a general election in the UK, in which little matters more than that, dominated by personalities and trigger points, our vote metamorphosed into a generalised tbumbs up or thumbs down, often on an aggregation of things.

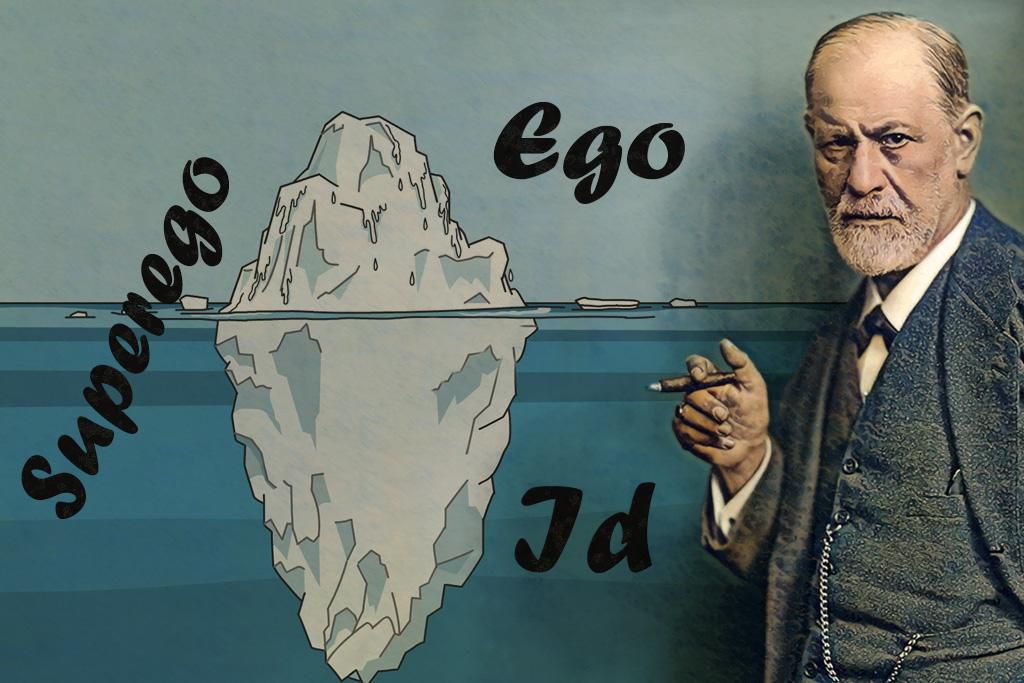

This question itself might be reformulated as ‘of things you like about yourself, which is your favourite thing’. And I cannot answer that, or not at least, without displacing it with a series of further questions (questions that proliferate and draw-out nuanced qualification of the verb ‘to like’ or ‘to dislike’); looking for some ground of rationality which may or may not exist. The great theorist of the primacy of the pleasure principle, the ‘prehistoric’ motive force of the world, preceding the acquisition of the conscious ego or ‘ich’ [more strictly translated as ‘I’], called the unconscious or id [or in German ‘es’ more strictly translated as ‘it’] was Sigmund Freud.

For Freud, the infant child who has entered the world of language, acquires ratiocination by expanding on the puzzle of its own pre-existence, soon deflected into the messy world of questions of sexual origin and the body’s implication therein. For Freud, the extended rational curiosity about the world that characterised Leonardo da Vinci was a defensive structure from problems he never articulated about sexual origin, turned into a generalised questioning for which the answers were so unattainable that, although secondary, their legacy lay in immensely valuable discoveries about the world of ratiocination instead. Yet having discovered the answer to each one of many mysterious questions, Leonardo was nevertheless never satisfied, and the drive to keep asking ‘Why?’ just continued.

That is to say. these particular and very specific answers to secondary substitutive questions Leonardo came up with, about tidal contraflow, ideal defensive structures for a city or the nature of flight, never satisfied his desire to ask questions again. He had to keep asking why, like the child locked in the adult. This is a mystery like that embodied in the smile of his hermaphrodite metamorphoses of the real, like the Mona Lisa or his precursor Baptists.

Had Leonardo just satisfied himself with likes and dislikes, then the world would never have been richer by virtue of all of his immensely valuable questions and some of his answers, which were not in themselves valuable, like the speculation on solo flight.

Hence, even if I decide that the aspect of myself I value the most is intellectual, sensory, and emotional curiosity, I can’t name it as a favourite trait of my personality nor just simply like it. 👍. Maybe that’s because curiosity does not serve pleasure alone and without cost, or at least unpleasure, accompanying it. Our wish to test whether a new sensation, idea, or feeling is likable may have everything to do with pleasure but to know about why it its distinctiveness sometimes does not appeal, or even repels, seem like hard questions.

Research costs time and involves moments of dullness, frustration, and pain. To grasp the meaning of what we learn costs more in testing our capacity to name or describe in full that which we once did not know or lacked familiarity therewith. Being curious to learn is to accept this. When we feel a necessity of our being is lifelong learning, it is a mistake, however, to think it is only indulgent in the learner, though it must be partly so.

Loving to know more is also an acceptance of the pain of being contradicted, accepting of the loss and invested feeling that comes from failure to know. and even the disappointment that even the latest ‘new’ discovery never satisfies the demand for moving beyond it to the penumbra of the unknown surrounding it. For those shadows grow in size, the nearer we approach any subject not yet comprehended. To understand that we finally know something once uncomprehended increases our awareness of its supporting network of things still not known or understood.

But this is the trait I feel most definitive of me, if not solely of me. Whether I like it or not is irrelevant. Hence, I can’t favour it as a trait over other liked features. I can accept its hegemony in my character and enjoy the ups and downs of living with power over me and driving me.

Love

Steven xxxx