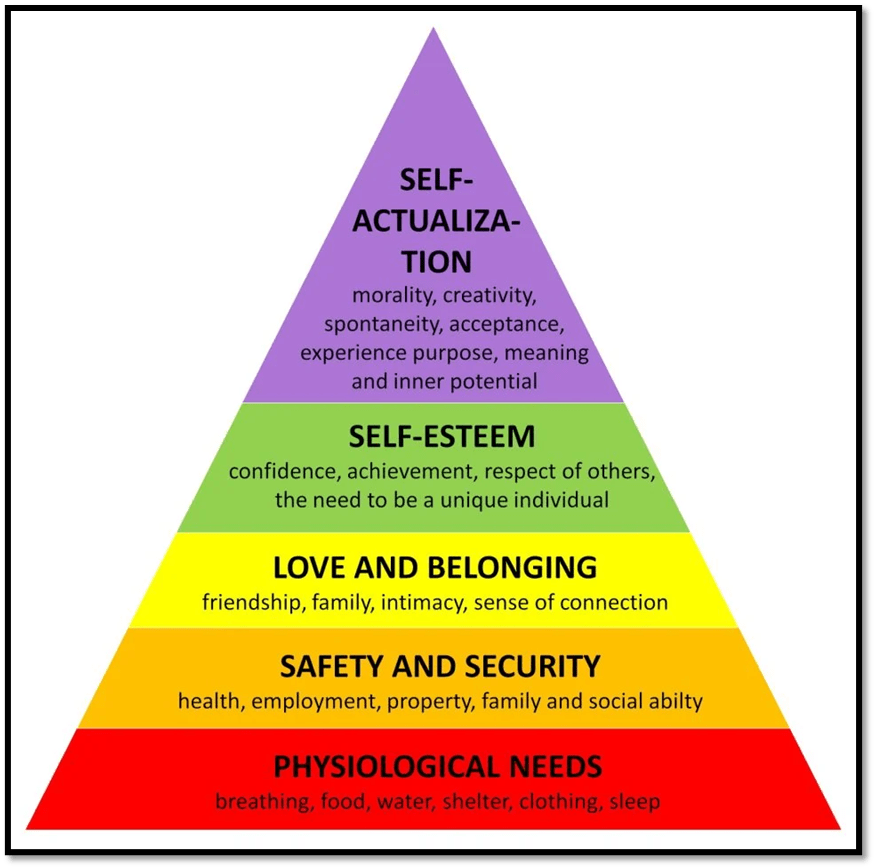

Abraham Maslow, the humanist psychologist created a ‘hierarchy of needs’ (it is pictured below using the simply psychology websites’ icon – because it is so simple). According to it (but of course I oversimplify) needs at a higher level of the hierarchy cannot be met before those at the lower levels, and these needs are, as we look lower more basic and fundamental to survival. I once wrote a blog (read it via this link if you wish) that queried whether, as King Lear in his eponymous play thought too, whether that model ever works. After all failure of self-realization is already a kind of base insecurity, sometimes to the point of suicide and implicates needs at every level. Sometimes, after all, basic needs like food or clothing or hygiene during waste processes are neglected as a result of a higher need like lack of confidence, or even on moral grounds, as in the case of people demonstrating principle or self-defining belief by refusing food (as did some Suffragettes and do some people labelled anorexic respectively), water, or clothes or on a ‘dirty protests’ as in the H-cells at Long Kesh.

Moreover, intended or not, the triangular model inevitably suggests that only a few ever realise the higher needs, since most struggle at lower levels.The apex of a triangle seems designed to represent tan elite or the existence of those in one way or other being fit for inclusion among the best – a natural or acculturated aristocracy. The assumption about those at the base of the triangle (which Lear will call ‘our basest beggars’ not as a ethical description of those people but of the reality of an hierarch at which he was once the apex are cut off from intellectual or spiritual good in their life by not attaining the steps between. This is patently not true. Try for instance trying to convince a practitioner of the act of the eremite holy of that belief. The triangle makes a simple point – without meeting physiological needs we die, but the truth is ever so more complicated.

Lear unhoused in a storm and raging at its attack on maintaining his most basic needs still tries to defend a luxury he once had and which represented him symbolically ny representing that he was, and still is, more than his basic needs:

O, reason not the need! Our basest beggars

Are in the poorest thing superfluous.

Allow not nature more than nature needs,

Man’s life is cheap as beast’s. Thou art a lady;

If only to go warm were gorgeous,

Why, nature needs not what thou gorgeous wear’st,

Which scarcely keeps thee warm. But, for true need—

You heavens, give me that patience, patience I need!

You see me here, you gods, a poor old man

As full of grief as age, wretched in both.

If it be you that stirs these daughters’ hearts

Against their father, fool me not so much

To bear it tamely. Touch me with noble anger,

And let not women’s weapons, water drops,

Stain my man’s cheeks.—No, you unnatural hags,

I will have such revenges on you both

That all the world shall—I will do such things—

What they are yet I know not, but they shall be

The terrors of the Earth! You think I’ll weep.

No, I’ll not weep.

I have full cause of weeping, but this heart

(Storm and tempest).

Shall break into a hundred thousand flaws

Or ere I’ll weep.—O Fool, I shall go mad!

Some allowances, some things considered luxury by some, are needed lest we fail in being anything at all but superfluous to life. Patience for Lear is a code of morality and self-realisation (some call it stoicism perhaps incorrectly given Charles Freeman’s description of the origins of that word in the description of Ancient philosophical belief systems), the highest in the hierarchy, but when I am a poor bare forked animal, I still need it and still need to know how to demonstrate it. Or else:

Is man no more than this? Consider him well. Thou owest the worm no silk, the beast no hide, the sheep no wool, the cat no perfume. Ha! here’s three on’s are sophisticated! Thou art the thing itself: unaccommodated man is no more but such a poor bare, forked animal as thou art.

And this strikes close to an issue I think about often – the stereotype of the thinking and the reflective life – the thing that rejects the ‘unexamined life’ in a version of Socrates’ words – is often thought to be a luxury. There is a case for it. I am retired on what they call a modest work pension (because my work life was so interrupted by my mental health) and I have time to ‘waste’. But I don’t see it as ‘waste’?

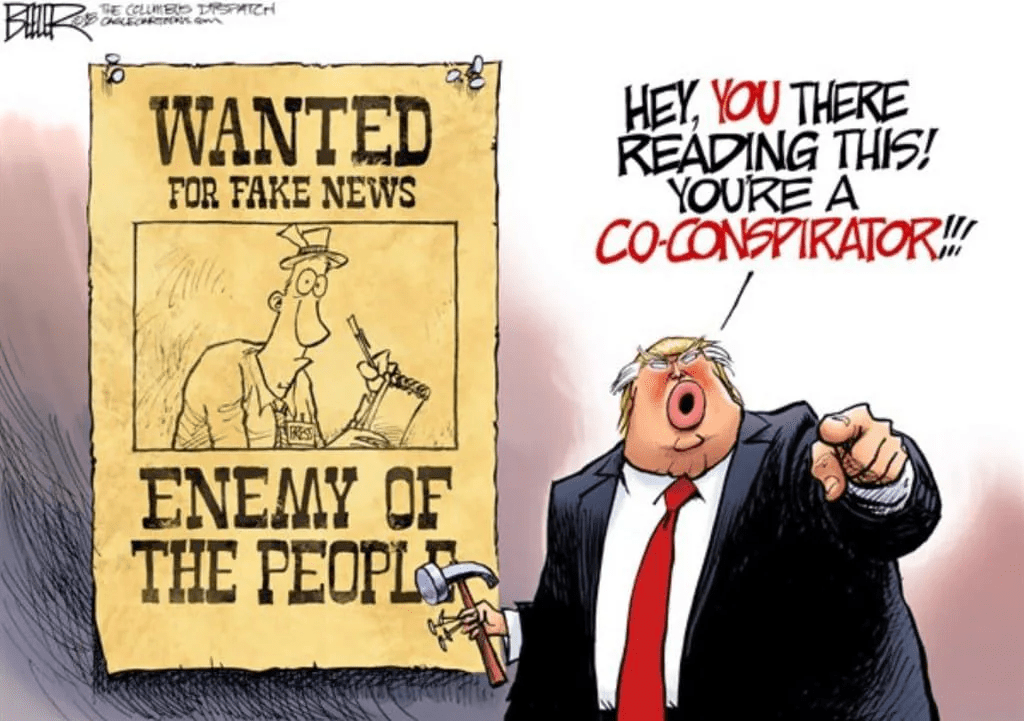

Anti-elite populism – stuff preached by people of great wealth and social status like Donald Trump, Boris Johnson, and Nigel Farage – is compounded of the nonsensical belief that people who think and reflect and suggest multiple ways of thinking about problem and thus support diversity are suspicious characters out to break the simple will supported by even simple thinking of people who cannot think outside the status quo. No wonder the new exempla of the privileged embrace their supposed commonness (Trump’s acquisitions of a working man’s look, for instance) and the links to some supposed majority of people who want nothing to do with airy-fairy thinking and posturing, as they see it, amongst intellectual élites of the ‘over-educated’ non-working class paid to have views, as they see it. The success of such populism may yet bring the world to extinction as the necessities of climate crisis and the intergroup violence associated with its untrammelled progress continue.

Meanwhile, I pick up Charles Freeman’s The Children of Athena, (buy it on Kindle – there’s a saving) . It is a book relevant to our question and in many ways a continuation of his erudite but quite readable last book on the 4th century AD of the closure of intellectual debate in many areas by powerful Church Councils, a thing given another reading in the defence of Catholicism in Cardinal Newman’s The Arians of the Fourth-Century. Freeman called his book The Closing of the Western Mind. By this he refers to the intellectual life and the training required for that life. The Greeks named the rigour and time one must spend on education throughout life παιδεία (Paedia in Latin – a transliteration of the Greek). Freeman chooses to spend time – a luxury indeed – on the fate of the training to think aimed at Greek aristocrats, most famously the young Alexander the Great under Aristotle’s tutelage, but which became a generalised principle in the thinking of later well-placed scholars in the period in which Rome had effective hegemonic control and rule of Hellenic Greece (the group of nations left after the failure of Alexander’s Empire) and its institutions. Byzantine ideas were in many ways a continuation of these and could support, until the Empire itself became strained (as Freeman tells) the idea of Paedia until a more rigid enclosure of ideas was required by a religion only semi-independent of the state, if at all after the 4th Century, that was the Eastern Catholic Church within the shifting Imperial borders if Byzantium.

Plato and Aristotle: paedia according to Raphael.

In Freeman’s book, neither church nor state felt it could afford the luxury of an ‘open mind’ about any issue of dispute after the 4th century. He sees the defeat and humiliation of the Church Father, Origen (who scoffed at the idea of a real Eden in the Creation, rather one of allegoric fable and saw life and the body as joyous unlike Saint Augustine, favoured in the Western Church) by the Imperial Church establishment as definitive of this closed approach to rhe intellect. This happened in part by the insistence of Emperor Theodosius on the Nicene Creed (named after the Church Council held at Nicaea) of the ‘consubstantiation’ that was the Trinity – the three in one of God, the Son and the Holy Ghost. The Nicene Creed was the achievement lauded by Cardinal Newman as an important stand against heresy. Origen’s thinking emphasised God the Father as a primal ‘One’, an idea he took from the pagan Neoplatonist, Plotinus, whose lectures he attended, as a friend of Plotinus’ acolyte and textual collator, Porphyry. So many fabulous names arise from that period of ‘Roman’ Greece up to the 4th century. However, the luxurious joy of this period lies more in the living belief that openness of mind was not a luxury per se but a necessity of right practice, practice that was tolerant of diversity, as we are led to believe Origen was. The evidence of Origen’s tolerance is wobbly, especially given his tract Contra Celsum, even as that work is described by Freeman. Yet even the latter was aimed at proving that ‘Christianity is as sophisticated as any other philosophy, in fact even more so …’. [1]

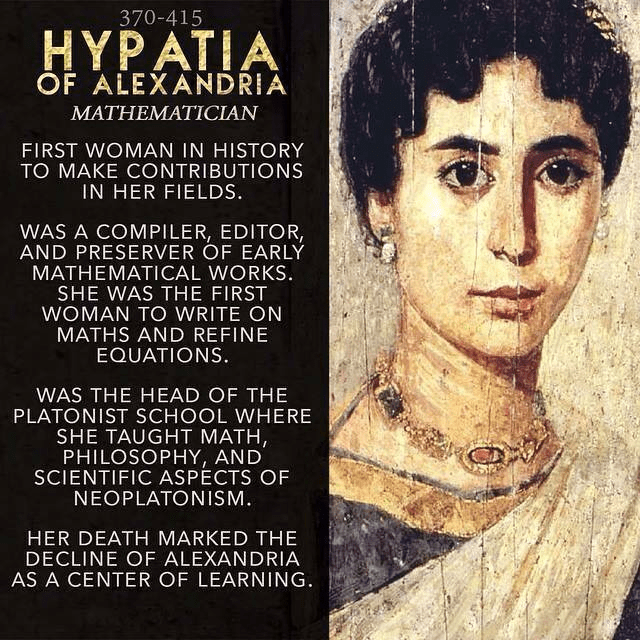

There are two ways in which Freeman defends Paedia as a disappearing ideology of open education, that might have (and did in some cases) break its class origin and stand for a common idea of education as a right of humanity rather than a privilege. The first is the well trodden story of the last cherished non-Christian believer, Hypatia, who was lauded by freer Christian thinkers like Charles Kingsley. In ancient Alexandria, she ran a school, with an immense library of rich works venerated by most if not populist Imperialists, which taught men and women and the follower of any non-violent God, including the Christian, Synesius.

The belief in non-violence is instanced, Freeman shows by the exclusion of Iamblichus whose works, though Neoplatonic involved participation in the mysteries of animal sacrifice, even if they were given allegorical meaning after the event). Freeman characterises the enemies of Hypatia, from the Patriarch Κύριλλος Ἀλεξανδρείας (Cyril of Alexandria) whom Edward Gibbon blamed for the death of Hypatia on evidence not clearly established, and the more likely culprit as told in Freeman’s version, Peter, a local church official in Alexandria who, like Tump at the end of his first Presidency ‘chose to form a band of supporters to confront Hypatia’ Again like Trump this ‘band’ was in fact a group of people, of which some part was dependent on Church charity happy to form ‘a mob’. This early populist political phenomenon was like crowds ‘easily inflamed and Hypatia would pay for her readiness to be out in public’. Freeman plays up Hypatia as a woman who wore the burden of great learning lightly, ready to show its virtues to all and ‘out’ in every open sense. For her pains she is ‘taken to a church at the seafront, then stripped and killed by being flayed with discarded roof tiles’. A horrible martyrdom worse than the case of many Christian martyrs but as Freeman says important symbolically in history because ‘it also marked the extinguishing of a symbol of elite philosophical learning’. [2]

If this was one way of encapsulating the end of an ideal of open tolerant education in a symbol, much of the rest of the book is more sober history, showing the last stand of thinkers who are now forgotten, one of whom was the near forgotten Libanius, doomed to be cited in later history only by free-thinking heretics or atheists for opening up questions the Church felt better closed forever. Who thinks it anthing but a waste of time to know of another late voice of Neoplatonism, Themistius.

The Classical tradition might seem to be comprehended only by followers of Plato in this list, but Freeman gives a history of Plato, and his usual rival in the standard accounts – thought of as more objective and positivistic in the Enlightenment if not in the Middle Ages, Aristotle. There are beautifully simple accounts of Plato, Aristotle and later ‘NeoPlatonist’ thinkers that show that sometimes people did not see them as so distinct from each other, especially those more learned and with access to the texts in the Arab and Muslim tradition, like Avicenna (980-1037) and Averroes (1126-98)’. [3]

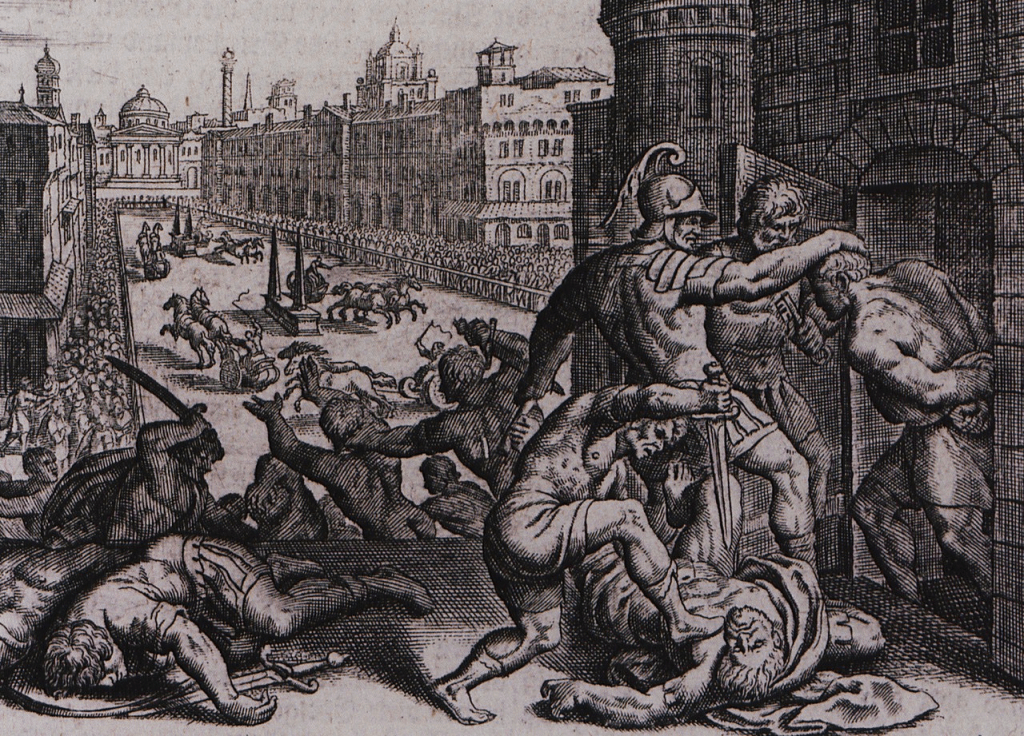

Freeman shows that even thinkers who are better known like Plutarch and Pausanias from the period of Roman Greece were often misrepresented and that later archaeologists were often surprised to find description of his travels by Pausanius backed up by indisputable archaeological finds.For Freeman Pausanias’ travels are evidence of the Western mind closing and demonstrating that by erasing and cancelling all signs of difference. His texts record ‘a mass of shrines that were still functioning , many of which had histories that were centuries old’: 2,500 in Alexandria alone. In its place came a Christianity institutionalised and closed in its thinking: ‘run by authority figures, the bishops, with a canon of texts, with the possibility of hellfire if one did not conform’. Meanwhile Themistius, a ‘pagan’ spoke of ‘religious toleration’. [4] Sometimes Freeman speaks quite freely of the disaster of Christian dependence in history (it happens more than you think) on a mob shouting slogans in the interests of the few (not necessarily and rarely themselves) against freethinkers thought of as part of the élite, because they were educated not because they had power. As Emperor Theodosius compelled the ‘Christianisation of cities, and empowered bishops to rule, he illustrated something new for: ‘Never before in the classical world had a single religion been defined and imposed as a doctrine. at a time of imperial breakdown Theodosius’ proscription marked a new emphasis on imperial authority’. [5]

The Theodosian Massacre at Roman Thessaloniki

A luxury we cannot live without is intellectual curiosity and reflection on it in the interests of a more complete life. It is not an add-on to the fulfilment of ‘baser’ needs but a thing that top-down informs thought, feeling and action like the Greek Nous ( νοῦς) on how we are all communally lifted and life, without institutional religion (God forbid!) having to impose a version of closed community upon us, for whatever reason of convenience to the real holders of real power behind it – the appalling Trumps of Doom of this world.

___________________________________________________________

[1] Charles Freeman (2023: 298) ‘The Children of Athena’, London, Head of Zeus, Bloomsbury Publishing. Pagination from Kindle ed.

[2] ibid: 343

[3] ibid: 58

[4] ibid: 370

[5] ibid: 306