Critics I have read of Colm Tóibín’s new novel, Long Island, have very correctly pointed out its reliance on minor deception, omission of truths and silence. But I think these intelligent critics are not sensitized to notice one of the minor characters in a novel as Tóibín’s loyal queer readers. Frank Fiorello has an important executive role in the novel nevertheless. Tóibín is, perhaps, the greatest (and most unacknowledged in this aspect of his role) queer novelist of the current literary age. When the feisty Eilis tells her Italian-American husband, Tony, that his brother Frank is not ever going to have a girlfriend because he ‘is one of those men’, Tony holds his breath in shock before he bullies Eilis into perpetual silence about it: “you will never say this again. Ever. Not to me or to anyone”.[1]

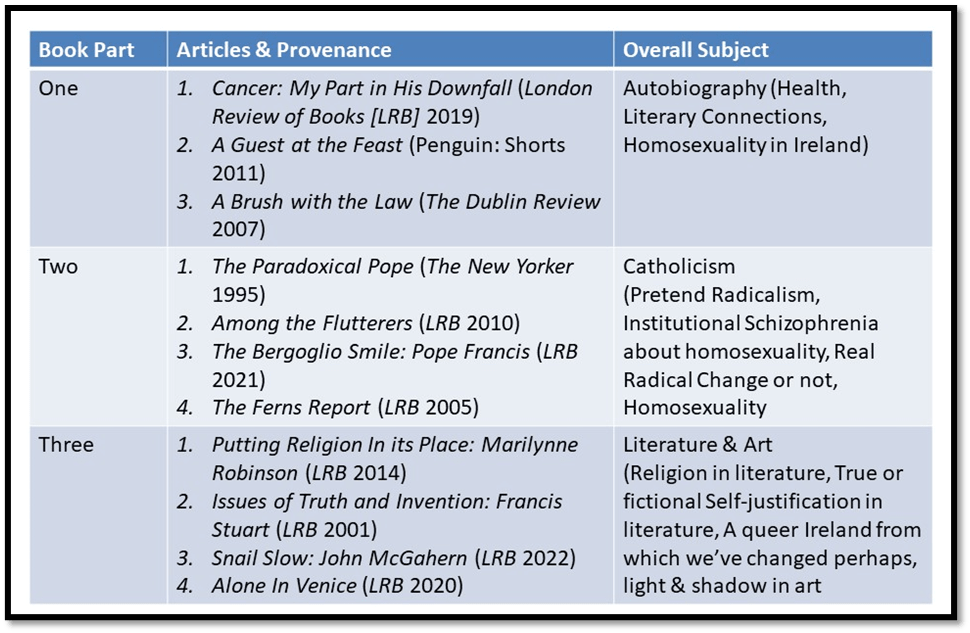

Colm Tóibín’s latest collection of essays (in 2022), A Guest at the Feast has a lot to say about queerness in Ireland, see, for instance, this summary of chapters from it from my own blog on the book (available in full at this link) but it says it from the point of view of being Irish and Catholic.

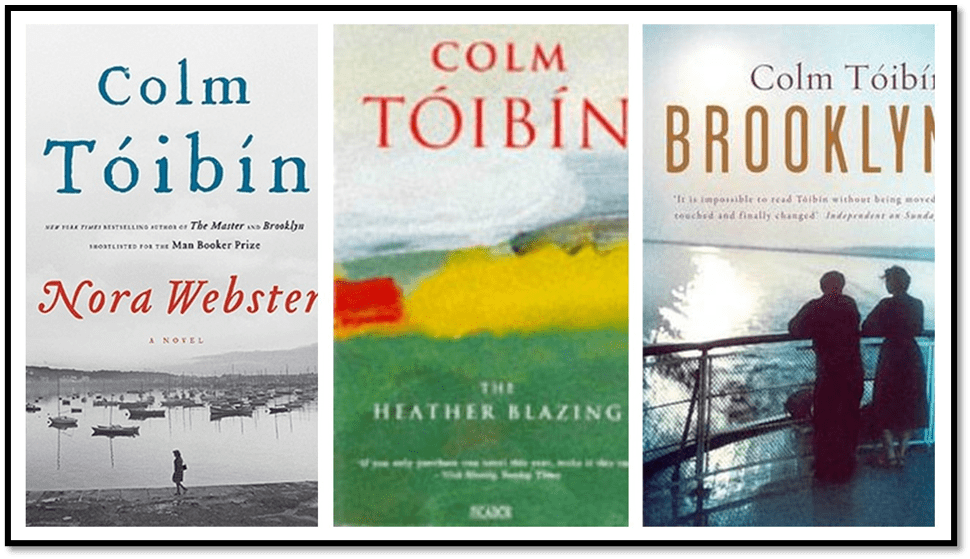

In his earlier and later fiction there are works that address being queer, with varying degrees of transparency often related to the narrative focus (The Master like Henry James himself is almost opaque) within this contes, particularly The Story of the Night, The Blackwater Lightship, the Master, some stories in Mothers and Sons and The Empty Family, The House of Names, and The Magician. Some of them occult the Irish interest (in The House of Names it appears in some of the incidents derived from Irish mythology rather than Greek). Brooklyn, though clearly a great novel, always secretly disappointed me because apparently (and in a mind that was then quite rigid if I say so of myself) it somewhat evaded that issue.

This is, I am sure, not because Tóibín was convinced that the novel of Irish provincial life could not cope with that, for after all The Blackwater Lightship is set largely in a cottage in Cush, and I have a notion that in her own novel, Nora Webster (who appears in Long Island’s scenes in Wexford) has a queer son. He knew and has spoken (in an interview with Seán Hewitt) of the novels of John Broderick (indeed in ways that made me read them) and has written on them in a fine essay which is the ‘Foreword’ to Broderick’s Stimulus of Sin: Selected Writings, posthumously edited by Broderick’s biographer, Madeline Kingston. Kingston’s book contains literary critical and other journalism and unpublished fiction by Broderick and Tóibín speaks of them as a near contemporary reading the works of a less acknowledged but great influence, if a somewhat demanding and acerbic critic.

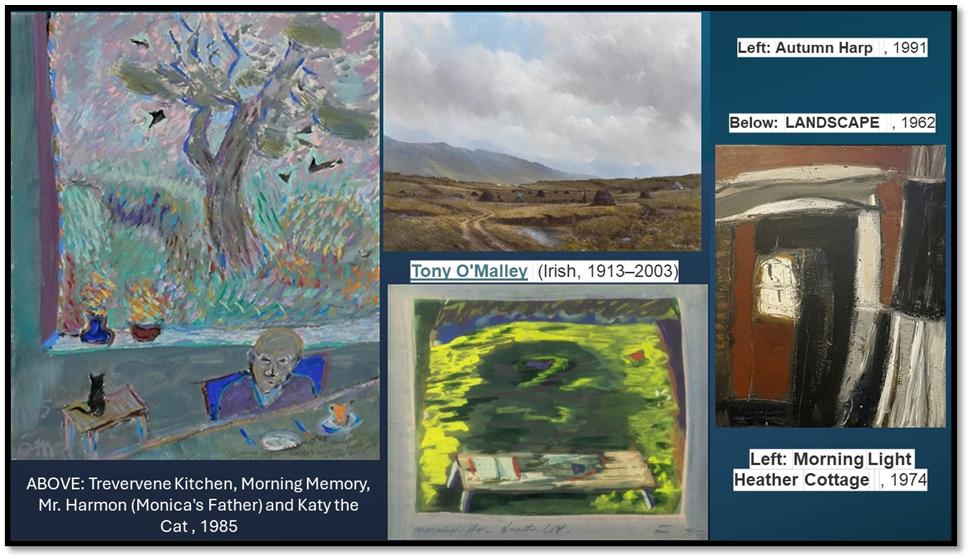

However, the introductory essay seems to me pertinent to Brooklyn and Long Island, for in it Tóibín does not speak a great deal about Broderick’s queer characters, who are legion but of his investigation of Irish spaces in the background of his novels, and those of John McGahern and Eugene McCabe. To the latter’s Monaghan and Leitrim settings he compares those of Broderick based on Athlone. But the point it we could add Enniscorthy too and its coastal Wexford hinterland as a similar space to these serving Tóibín himself: real places which have ‘slowly become a distilled form of personal iconography, close to mythology’.[2] Those words are used in fact of the painting of Tony O’Malley, but the same issue arises for the novelists in the next paragraph.

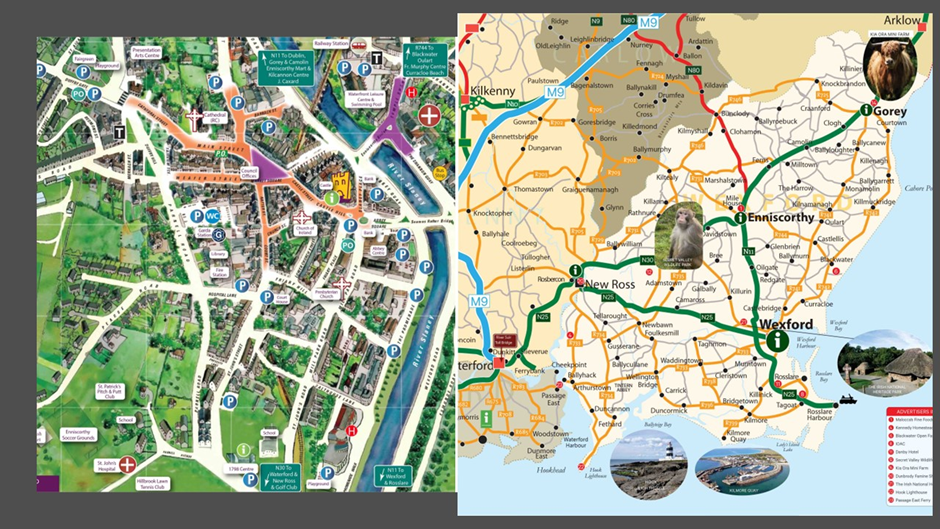

Enniscorthy, Courtown, Blackwater, Cush, Wexford and down as far as Waterford to the South and, of course the road and coast to Dublin in the North matter as an immense weight of meaning to Toibin rather than being merely settings to events in the lives of the novelist’s characters, as they do in Broderick and McGahern. Their mythic and iconographic status has grown from the publication of The Heather Blazing (1992) to Brooklyn(2009) and Nora Webster(2014). There seem echoes of all these novels, if of course chiefly in its nature now as a prequel as a narrative of the character Eilis Fiorello, in Long Island There is meaning to the geography and temporal structure of the life of the places, the turns and dead-ends (‘a tiny detail in streetscape or landscape’), the vistas from cliffs or up close on a beach or in a crowd in towns, and the ‘systems of speech and dialect’. All of the latter aggregate meanings in the novel as they do in mythology and iconography. In speaking of Broderick, Tóibín uses phrases he quotes from Brian Fallon analysing the use of space within the landscape of community as a theme in Tony O’Malley: ‘a certain sense of an enveloping fatalism’ that is ‘felt by everyone and permeates the small, tight world’[3].

In speaking of his forebear novelists of provincial Ireland, he could be speaking of Long Island, though Dublin would have to be supplemented by a further adventure in space and time travel, The United States.

The possibility of an escape from the cocoon of fatalism, thus becomes an important engine in the drama, making the city of Dublin for both McGahern and Broderick as important a stage as the one where the characters are born or come from. …/… Both writers wrote About family and locality and isolation because they were fascinated by the literary possibilities of Catholic ritual and rural romance. Both of them also that power of sexual imagery and sexual frankness in a world where such things were not often mentioned.[4]

I mentioned in my title that intelligent and sensitive criticism is alive to these mechanisms of silence and suppression. Let me give some examples. Clare Clark in The Guardian points to the fragility that comes to most of the relationships from the ‘steady accretion of small deceptions’.[5] Indeed it does. Róisín Lanigan in The Literary Review mentions that every character ‘hides their interior life, the complex motivations that stop them saying what they actually think’.[6] There are various absolutely telling ways in which in which both perceptions are handled by Tóibín, proving as he handles them his superb grasp of the novelist’s craft, for the handling of secrets unbeknownst to others and the interaction of individually internalised or projected views of the world is how novels handle drama. Think, for instance of the trip to Dublin made by Nancy and Jim, where each contemplates life with the other, using the trip itself as an exemplum of their worthiness of each other.

We get Nancy’s version, entirely from her point of view first. One beautiful thing is hoe each described the manner, tone and significance of how they communicate together in the car. Third-person narration but written from the perspective of a character often helps a novelist to show how the unspoken words of the character interact with and interpret the outward action and direct speech of a scene. Nancy is entirely self-conscious and uses that consciousness to gauge her speech in the car to Jim, to compare it, both favourably and unfavourably, with her experience of the same with her late husband George and play games about how much information she gives Jim about Eilis, given her knowledge of their former relationship. It does all this in an economy of great writing:

From: Colm Tóibín’s (2024: 111) Long Island London & Dublin, Picador

As momentarily Nancy thinks about what Jim is ‘thinking about’, the prose jumps, like the process of her consciousness to what to tell Jim about Eilis, but on finding in doing so that she had ‘spoken without thinking’, she quickly invents another story – about meeting ‘Sarah Kirby’ (who is gossiped about at Miriam’s wedding) so that Jim ‘s attention is not drawn by her to someone she sees, deeply and not with total recognition yet, as a rival for Jim’s commitment and attention, a commitment she may not have yet fully made herself.[8] It is beautifully done.

Later we get this aspect the same journey recounted by Jim:

From: Colm Tóibín’s (2024: 136) Long Island London & Dublin, Picador

What is brilliant about this brief recap, some 25 pages later in the novel, and where much plot is developed between the passages, Jim thinks of their journey entirely differently from Nancy. Her taciturn anxiety about saying the right thing or not being responded to and stimulated is interpreted by Jim as Nancy being ‘silent’, but with there being ‘no strain in the car when she didn’t talk’. In the prose as directed by Nancy’s consciousness there was in fact much edginess and nervous energy, quite unlike the calm sentences with which Jim gets it all wrong about her.

We are not far here from Tony O’Malley’s country town ‘where everybody knows you and your family, or at least knows about you; every birth or death’ (or engagement, marriage or affair we might add) ‘is a kind of communal event, and there is a certain sense of an enveloping cocoon of fatalism’, for this is the context of both silence about personal life and the origin of small, and even larger deceptions, like the waxing onto a finger become too fat of an old engagement ring from your former and now dead husband to pass off as that given to by a potential new and very much sexually alive one.[7] Fatalism is bound up in the street plan of Enniscorthy or the lanes to the beach on the Wexford Coast at Blackwater, and in the means by which the characters plan to travel between places – the location and sighting of cars taking on great prominence and heightening the role of Frank, for it is only the money he gave here that allowed Eilis to have a car and thus secure escape from her mother, her children and events closing in on her, only to find that when people have cars they can both act as means of transit and be observed to evidence your whereabouts, and hence there is no escape from communal observation and subsequent trial narratives that people tell to form an idea of your otherwise incomprehensible hidden life.

This is the kind of thing that the critics I cited noticed I think, an overt concern with secrets consciously and unconsciously kept, the latter when the person, like Jim, is less aware of his excitement about Eilis than we know him to be and more confident in engaging Nancy’s attention and sexual interest than Nancy is, still unsure that Jim won’t always be a poor exchange for ger George in conversation, bed or car.

Inside of Enniscorthy, eyes can only be evaded at night and using secreted entrances to buildings, as in the conduct of Jim and Nancy’s affair in his upstairs flat, hidden from the town (or so the ‘lovers’ wrongly think for they are observed – we will earn much later in the novel – by eyes that don’t sleep). Alternatively cars are the means by which, outside of Enniscorthy, eyes might be escaped, or it is thought they will be. The small roadmap of Wexford below (I visited the county and each of the sites with my husband many years ago)show the main road between Gorey and Waterford passing through Wexford, all places in the novel and the Wexford Bay Coast Road off which many car-journeys find conjunction, and supposedly hidden love and sex or a road towards it.

Just before Nancy, haven driven down to Cush, squats on the cliff above the beach there to eventually seen Jim and Eilis in ‘intense conversation’ in the low distance before a kiss, she is already aware of what she thinks she will see because as ‘she made her way down the lane, she saw Jim’s car parked straight ahead. And the car parked in front of it was Eilis Lacey’s rented car’.[9] Cars take Jim and Eilis to a Dublin hotel the night before she picks up her children, the car that Jim takes to Nancy’s daughter’s wedding at the cathedral is left behind allowing Nancy, once she sees it, more information about her having a sexual rival.

But the novel also grasps how to describe groups of people who are treated as alone in their head as each wonder what the other is thinking, as we have seen with Jim and Nacy above. The whole is probably illuminatingly treated in terms of psychologists call the ‘theory of mind’ but even I won’t go there, since such a discussion would carry with it a kind of cold objectivity that is not the feel of the novel. Many times in the novel a character will imagine the response of another and gear their action to the imagined response, often by neglecting to act or failing to speak, or changing the detail of their account of an event. People claim, like Nancy with Jim looking at a possible new residence for them after marriage, that they can ‘tell what was going on in his mind’. However, we have already seen that she gets it wrong (about the car journey conversation To Dublin for instance).Sometimes people wish they could tell more of themselves to someone but still don’t, as In Jim’s first conversation on the beach at Cush.[10] Sometimes the thoughts people have about other people’s thought in volve counterfactual as in where Jim wonders , though he feels easy with her being bound to him at a distance but ‘not far away’, whilst wondering what ‘would Nancy say now if she came into a room, and found, a thing still ‘barely credible’ to him that Eilis was still in his flat late at night.[11] Likewise people try to imagine the desire of another for themselves or a third person, weaving strange narrative plots. There are fine examples at Miriam’s wedding.[12]

Eilis and Jim, Nancy and George in Brooklyn (film)

Likewise sometimes narratives derive not from what you know but what you don’t know and have to guess. Thus Mrs Lacey never mentions Jim in her letters and he lives the stronger in Eilis imagination. Nancy enjoys ‘ the idea that no one, no one at all, knew about’ her and Jim, ‘and no one, she believed, even guessed’. Tony is never mentioned In Eilis’ letters to her children. Out of such absences are cocoons of fatalism made.[13] And out of absences, lies are formed to fill an abyss of not knowing and lacking control for that is what stories are about. Lies are usually stories in this book with invented additions to things otherwise facts or omitted facts that change the tenor of a story. When direct lies are not told, half-truths do. Sometimes communication is so subterranean living in the gap between two people’s knowledge of each other and themselves 9both kinds of knowledge being faulty) that what each understands of the other is a mutual construction but still fragmented. Look, for instance at the complicated negotiation of increasing closeness and engagement between Nancy and Jim, where a botched statement is seen in its genesis, possible negation and accidental spillage. There are some many conditionals and counterfactuals around this event though, before the reader and Jim realises the narrative act is completed. This is novel-writing of the highest order:

He realized that there was one thing he could say now, and if he said it, then it might be noted by her. He wondered whether, if it had been any other day, he might have held back, but by that time he had already spoken.

The ‘cocoon of fatalism’ of small-town talk is precisely laid bare by the fact that because everyone weaves a narrative, some sometimes accidentally connect and create a wider knowledge of a secret story than was intended. This is the key reason the book revolves around Jim’s ‘engagement to Nancy, real or fancied. He leads the way in making the engagement stick only to find it difficult to retreat as Nancy is folded in and finds herself comfortable. At the end we do not know what he will do – honour the truth behind Nancy’s lies about an ‘announced’ engagement, run away (his favoured option – to Dublin and thence USA – and he hope to Eilish, who really never commits as she did not in Brooklyn.

My use of the tradition of Broderick and McGahern might suggest that this is all VERY ‘Irish’ and Lanigan disappoints me when she says that: ‘In a quintessentially Irish way, the book relies on what’s unsaid as much as what’s said’. It’s true but is it necessarily Irish? There is a reason that Tóibín gives both novels that are now in sequence names from the USA. In an Imagine programme on Brooklyn, I remember Anne Enright saying that people come to Irish novelists for material on family secrets and conflict and argues they ought to go to their own cultures and write their own family-intense dramas. The point is there endless ways of pretending that because a theme is well-placed in an Irish historical country-town setting, it only talks about that setting.

In talking about Broderick, I think Tóibín is actually saying that Ireland provides the mythographic and iconographic setting for universal stories about persons in relationships – political, social and romantic-sexual. There are hidden stories shared in America about how the ‘violent histories’ of both Armenia and Ireland create a BOND between Eilis and Mr Dakessian, the garage owner who employs her, because, after telling her of Turkish massacres of her people he says he found a book ‘on Ireland and what happened there was a bad as America’.[14] These are contexts we easily miss but they illuminate another version of what Irishness is – not oppressive ritualised gossip but a communing against foreign oppression. Likewise the children bring meta-Irish history into focus by each telling garbled stories of The Great Famine (on which Tóibín has written a nationalist history) and the life of Bernadette Devlin.

But the other reason we can over-Irish the novel’s themes is that they commence, those secrets and lies in families and tight communities in the Fiorello family enclave, in the tightening of saving narratives around Tony’s child of a woman whose plumbing he was doing, in a rather metaphoric way as the woman’s Irish husband tells Eilis. The join together to exclude and marginalise Eilis. She goes to Ireland to escape this, In the Fiorello family, and other American families – migrant by default – lies are told, secrets kept and half-truths used to cement real contradictions and painful ruptures of relationship.

If Lanigan thinks the novel is just about Ireland she knows, there is no way she will notice the story of Frank Fiorelli. For as Anne Enright reminded us, if other nations didn’t have family secrets at their heart, there would be no The Oresteia, Oedipus Tyrannos, Anna Karenina or Middlemarch. As I continue to think about Frank Fiorelli, I cannot help thinking about his suppressed sexual life and those of others who can be said to be one ‘of those men’ referred to by Eilis to Tony. For Frank must too have a sexual life, even if it’s a chosen asexuality but it is never revealed. Indeed, even a coded and homophobic label is banned by Tony but not because it is homophobic.

Nevertheless, I must try to resist the temptation to see Frank’s hidden sexual story as connected to what Tóibín calls Broderick’s ‘sexual frankness in a world where such things were not often mentioned’, for with Broderick queer people were ubiquitous even in midlands Ireland, nearer the truth than any great tradition or catholic canon. Though McGahern was forgiven, for his transgressive novels were heteronormative, Broderick was not by the Catholic Church or literary establishment. Yet Frank is a frank name to give someone whose very being is far from being ‘frank’ in terms of his sexuality. And since I haven’t resisted the temptation, I suppose I want to insist that Frank is important to this novel in more ways than that he makes certain things possible in Eilis’s life, by his decision to be open about secrets the rest of her family wanted keeping from her and financing important (and central to the plot of the novel) aspects of the journey like a car. He matters because the suppression of Frank’s story continues to be active well after Eilis has opened up many options for her future, married to one of two men or neither. Frank is forced to continue less than frank.

Moreover, if this is a novel of Irish deep social duplicity, it misses the fact that the diaspora Irish who return to redeem it from its benightedness, including Eilis’s very successful entrepreneurial brother who buys people houses, even Eilis, often get what is happening in Ireland wrong. Critics get that wrong too. Clark says that: ‘In Enniscorthy little has changed’. But the diaspora Irish who get lucky often too get blind to Irish resilience.

Eilis in Enniscorthy on first visit, from film

When Eilis gets to Ireland she uses Frank’s money to but kitchen white goods for her mother convinced like Clair Clark that ‘nothing had changed at all in the house since she had left more than twenty years earlier’. She means well but fails to consult her mother about the new goods and hence patronises her. It is only when she is well settled in that she realises that her mother can organise her home for yourself, as she does while Eilis is in Dublin for two non-communicating reasons of having sex with Jim and picking up her children at the airport. She even later learns that Mrs Lacey can build a better relationship with her grandchildren than she herself does as their mother, and has not communicated with Eilis fully because Eilis is, after all, incapable of comprehending the virtue of her Irish heritage. The difference lies in an attitude of patience and reading oneself for change and understanding what in changes imposed are necessary and what not. Ireland is making that very progress now. Let’s not think that the Irish are best in showing us just how dark the relationships in families and couples can be.

If this is not a queer novel, long Island, and it isn’t, it is because it rather wants to explore the processes by which the non-normative sexual choice is followed and those mechanisms are still there to see in supposedly heteronormative societies, like Tóibín’ Enniscorthy. Lanigan thinks the novel much the worse because we leave Jim on the cusp of a choice between two women, one of whom may well feel she has been lied to enough and will not reflect that she did the same to him in the first novel. We even leave him know a counterfactual imagination of speaking to Eilis is really nothing more than being kept out by an open door, a wonderful symbol. We leave him ‘ready to answer the door’ (his own this time) ‘when Nancy came at midnight and meanwhile ‘do nothing’: ‘That is what he would do’. Conditionals and counterfactuals. It takes a little openness to get beyond them. I have more faith that Frank will break his bondage to false norms long before Jim will do. It’s a wonderful novel.

Do buy it and read it. A Booker surely!

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxx

[1] Colm Tóibín’s (2024: 24) Long Island London & Dublin, Picador

[2] Colm Tóibín (2007: xi) ‘Foreword’ in Madeline Kingston (Ed.) Stimulus of Sin: Selected Writings of John Broderick Dublin, The Lilliput press. xi – xv.

[3] Ibid: xi

[4] Ibid: xii

[5] Clare Clark (2024: 51)’Happy ever after?’ in The Guardian Saturday Supplement (Saturday 18/05/24) 51.

[6] Róisín Lanigan(2024: 50) ‘Beyond Brooklyn’ in The Literary Review (Issue 530, June 2024) 50.

[7] Tóibín (2007) op.cit: xi

[8] For more on Sarah Kirby in a conversation at the wedding, see Tóibín 2024 op.cit: 153

[9] Tóibín 2024 op.cit: 264

[10] Ibid: 147

[11] Ibid: 178

[12] See, for instance, ibid: 158

[13] Ibid: 38, 58, 80 respectively

[14] ibid: 17

7 thoughts on “A queer perspective on Tóibín’s ‘Long Island (2024). When the feisty Eilis tells her Italian-American husband, Tony, that his brother Frank ‘is one of those men’, Tony holds his breath in shock before he bullies Eilis into perpetual silence about it: “you will never say this again. Ever. Not to me or to anyone”.”