The answer to this prompt question (‘What are the most important things needed to live a good life?) has to be one based on how and who we love and value outside the circle of what we call me. But you cannot achieve such things easily and they are often obscured and misrepresented. We have to struggle to understand them. This blog uses a great new book on queer community in Brixton to show how and why this can be so, Here was the working preparation on the book. My thoughts regarding the prompt question are implicit in it.

Jason Okundaye says the kind of research he does’ a rescue effort and a race against time’ as he pursues stories that define the lives of diverse black queer lives that might otherwise ‘be lost for ever’.[1] But he also thinks it is an act of collaborative creative invention where the there is a ‘deliberate blurring of the lines’ between the interviewed and the actual witness of the stories who is interviewed.[2] The problem is defined in a poem by one’ of his interviewees, Dirg Aab Richards as rewriting from the ‘works of a white man’: in order to find ‘What wasn’t there but was’.[3] This is a blog on Jason Okundaye (2024) Revolutionary Acts: Love & Brotherhood in Black Gay Britain, London, Faber & Faber.

Whilst all of the six key people interviewed in Jason Okundaye’s book knew, or knew of, each other the acts they contributed to creating the space, or a part of which that (from wherever it sprung – Manchester or Huddersfield feature in it as places of origin – mainly gravitated to London and to Brixton in particular) which we can begin to recognise in this book as ‘Black Gay Britain’. They knew each other and some were friends. Some looked at others with a degree of suspicion or distaste. Reviewers can describe that in ways that do not dop justice to the feel of the book and the binding quality of the narration so that ideas like community and diversity, consensus and debate (sometimes with a kind of temporary divisiveness within it) are not seen as opposed to each other but complementary qualities. They holding together of contradictions ought to be, after all, a rich quality of huma societies that embrace change and understand both the desire to change them and the limits within which that might be possible. Thus in The Guardian, Lanre Bakare says:

As you might expect from a community that existed largely on the margins, life could be difficult and dangerous. Police raids at cruising spots regularly punctuate the stories, but so do the fabulous parties and, indeed, petty squabbles that rage for decades. It’s a messy world, where destitution never feels far away, but success – financial, romantic, professional – is also within reach.[4]

There is something that unintentionally patronises in these sentences Okundaye and the worlds of the elders he describes and the real conditions from which those worlds sprang. Maybe too there is somewhat too much of a feelgood factor in the Bakare’s representation of the book’s subjects. The book is joyous in representing community but it constantly fights back against presenting those communities as unified in intent ,easily integrated or joined-up in vison, method or voice. In Chapter 5 (‘The Scene’) he asks us to see the ‘Black gay scene’ as ‘one thing and many things’ where: ‘At its best and worst it’s riotous’.[5] And here is where we can agree with Bakare that the world described is a ‘messy’ one. As he describes contests between his interviewees and the fact that many of them think the scene itself, even the ‘cottage’, a queer cruising site, that was the toilets in the now Windrush Square deserved a ‘blue plaque’ to denote its historical-political significance he knows the ‘general reader’ including modern queer men might find that ‘not particularly worth defending’. But he insists that ‘messy; is what real sexual-political social history is: ‘Our history as Black gay men can’t be sanitised. It must instead be invested in mess, and this means the literal, physical, pleasurable mess of the body, and not just conflicts and catfights (though I’ve loved getting into these too)’. If we read that again and compare its tone to the Bakare passage above the tonal comparison is here and where I find the latter patronising.

Michael Donkor, in the i newspaper, gets Okundaye’s tone dead right. He speaks of the book as creating its theme in its mode of address and style to its interviewees. The theme is honouring ‘living figures’ and therefore ‘offering gratitude underpins the writing throughout’ He goes on to say that there ‘is a radiating warmth in its tone’ and that it communicates by Okundaye: ‘Expressing himself in narration that manages to be both embracing and erudite’. I totally agree and part of that warmth is a kind of mutual joy in ‘campness’ with some, especially Ujuma X who praises the attractive width of Okundaye’s bum and thighs: at which point the interviewer notes he will never wear tight shorts to work again, not that he wasn’t in part enjoying the attention. Similarly when he wonders if it is right, with each interviewee, to know each as either an ‘uncle’ or a ‘Daddy’ (with all the weight the later term bears in queer culture). Of course he tells us that he won’t share each individuals answer to that question but I think we enjoy the guessing we can do the better for that. Likewise there is warmth in sharing moments of nostalgia, sadness or grief with others.

And, in the end, our warmth is shared not only with a community but is setting. This piece again from Donkor is excellent, in which the gratitude of one intelligent Black gay male critic for another Black gay male scholar of their shared backstories is evident:

Brixton is the text’s nucleus, the heart of the “scene”. … Currently disused public toilets in Windrush Square and Pope’s Road, for example, used to be thriving “cottages”. Gay Black men met here not just for steamy fumbles but to share gossip, spot new and familiar faces, feel a sense of recognition lacking elsewhere.

Equally, the nightclub Substation South, once tucked away behind Brixton’s thronging main thoroughfare, hosted DJs like the legendary Biggy C. Its dancefloors resounded with “Chicago Deep House and soul” and sizzled with the moves of Black gay men. The building is now a fairly nondescript and rather expensive co-working space. Okundaye’s conversations – exchanges that become even richer as these “elders” share flyers for these nights, posters for meet-ups, newsletters of organisations like the Black Lesbian and Gay Centre – invite us to look again at seemingly familiar sites and commonplace assumptions about the narrowness of Black British identity. The repeated encouragement is to think again, to note what has been consciously left out or overlooked.[6]

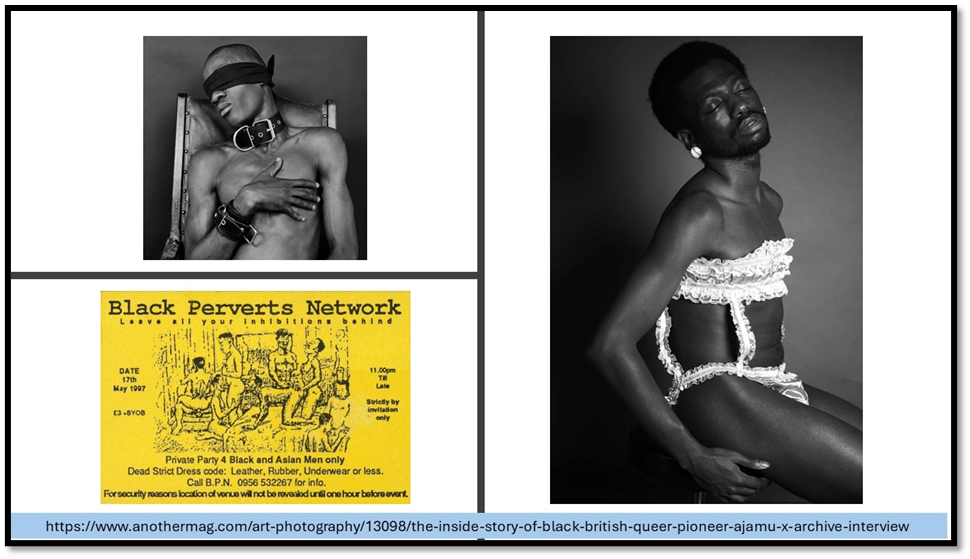

Let us think then now of some of the 6 people honoured and their commonalities and differences, agreements and divisions. Ted Brown, a hero of the early Gay Liberation Front (GLF) sought to secure a ‘more positive representation for LGBT people in the media’, and especially of black gay men.[7] That could, I think he thought be hard to do if he had been in full collaboration with say, Ajamu X, a photographer committed the defence of ‘fetish and fantasy’ in lived queer lives, even in public, and he helped build for these men their ‘own unapologetic spaces’, included the organisation Black Perverse Network, ‘ a safe sex party space bringing together Black and Asian men’.[8]

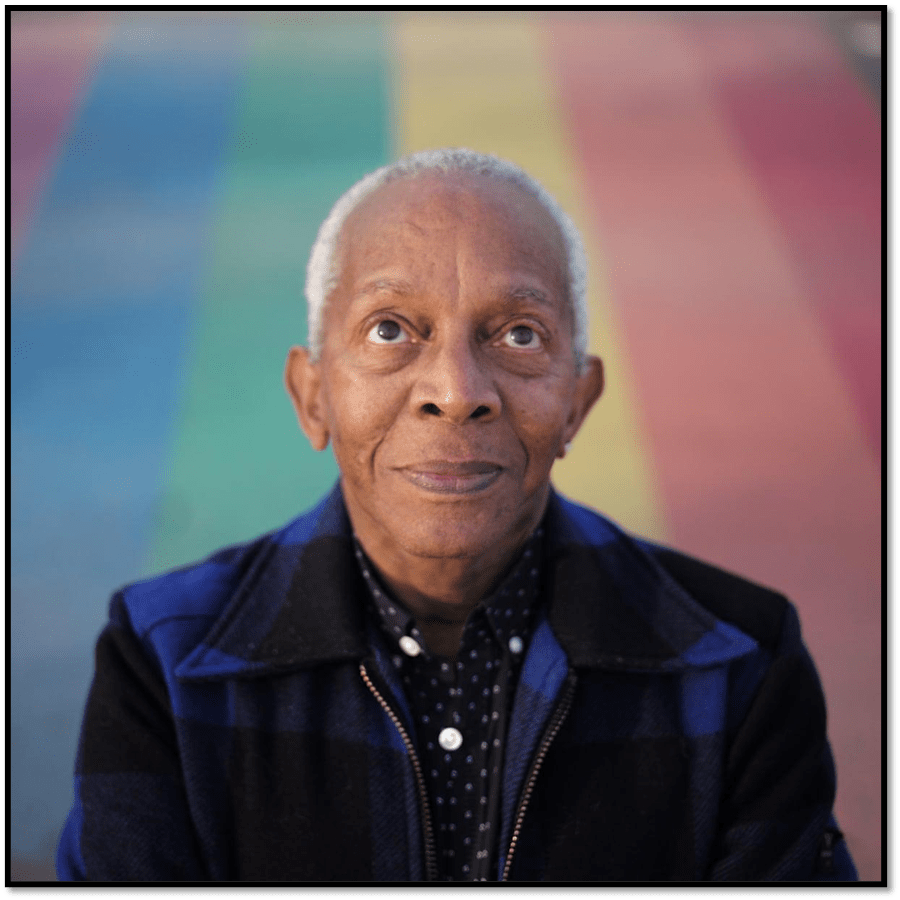

Ted Brown from: https://www.anothermag.com/art-photography/13098/the-inside-story-of-black-british-queer-pioneer-ajamu-x-archive-interview

It is not that Ted Brown would disapprove of Ajamu personally but that he felt the political fight required an image all gay men would be happy to publicly support and which did not collude with negative stereotypes of queer people of the past. As Ajamu says of reactions to his photographic images of Black male nudes participating in public sex or wearing sado-masochistic sex toys or clothing: “ I used to get a lot of flak in terms of the early work from Black gay men, because my work wasn’t seen as “positive representation”.’ However Ted Brown and everyone else in the group, other than himself, definitively steered clear of Alex Owolade, describing him as a ‘hard loony “leftish”’ person, unwilling to compromise with the status quo.

Alex Owolade believed in the creation of a caucus of radical and left-wing Black Men, who got together as a group named the Friday Group with some presence from left groups, and which had great trouble in being represented by the committee of the mainstream Black gay movement, especially the Black Lesbian and Gay Centre (BLGC), The BLGC had a shoestring birth, assisted by Gay’s the Word Bookshop and the Marchmont Community Centre in Bloomsbury, whose administration, and cleaning up after the people who thought themselves too busy to do it, was done by Dirg Aab-Richards. The Friday Group, run by Alex, came with the Greater London Council (GLC) funding – so opposed by Margaret Thatcher and leading to the demise of the GLC in part – as run by Ken Livingstone.

Dirg is one of the few to still favour Alex, but that was perhaps because he noticed an analogy between him and the Red revolutionary, in the meticulous care to detail in order to get things done. Otherwise the BLGC refused to formally recognise the Friday Group. It was though a life that could be looked back on for successes. Okundaye says that ‘one of the most moving details of all the interviews’ he conducted included a moment where Alex ‘breaks down’, explaining his urgency in pushing ‘black communities to challenge homophobia and engender empathy towards lesbians and gay men’ and marching them to Soho, because gay pubs there, mainly frequented by white gay men, had been bombed. He weeps at the memory of Black people raising their hands in salute to gay people, whether Black or not. However, also, for his part, Alex saw he others interviewed in the book as ‘sells-out’ to white patriarchal capitalism, for people sometimes refine what they are willing to count as a ‘revolutionary act’.[9]

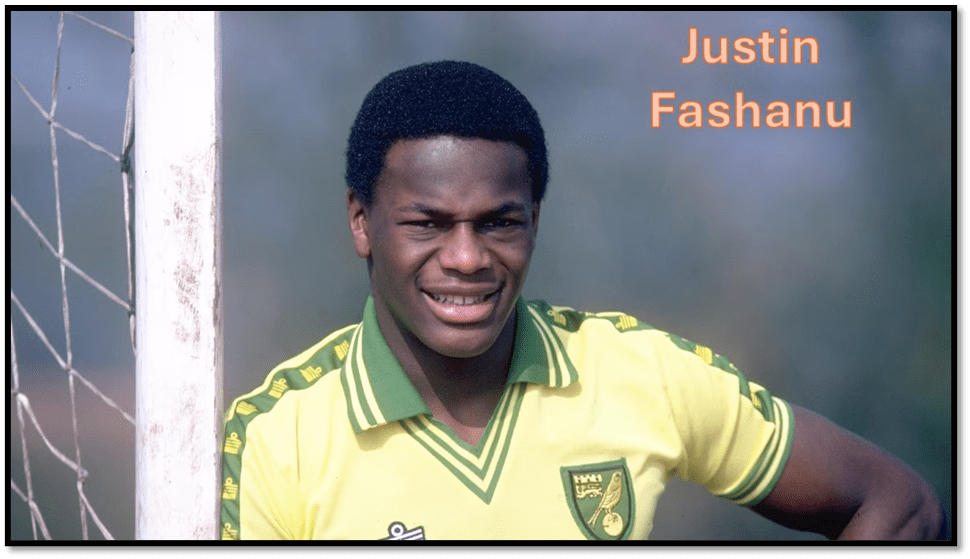

These men then were not of the same mind about what constitutes acceptable change or was a ‘revolutionary act’ in the interests of creating a visible presence for Black gay men. Even the causes they supported showed this, such as the work done on behalf of the outed footballer, Justin Fashanu. He was descried as insufficiently representative, and indeed a disgrace to the Black community by its main media organ Voice.

They supported John Fashanu, Justin’s brother, in organising family and community response to him as behind a chilling headline of a story he contributed to Voice: ‘MY GAY BROTHER IS AN OUTCAST’ (the full story is detailed in Chater 4 of this book and we must remember that John Fashanu is now a great supporter of his brother’s memory as a Black gay man).[10] Alex’s support of Justin was unfailing as was the work of both Brown and Dirg, as with others, although Justin himself, a very complex person, influenced heavily by the gains to be won by staying within the realm of those for whom the status quo appealed. His suicide followed a claim that he had raped a young man in the USA. But complications aside Justin was no revolutionary in the interests of Black gay men. It is not for the entitled white however to judge that situation – for oppression always comes with contradictions for those exposed to it. However, when the mild gentleman, Dirg, offered to facilitate a safe space for discussion in a solely Black audience when Justin had been attacked in The Sun, and Voice following their lead, Justin refused Dirg. Okundaye continues Dirg’s story thus;

It’s clear that, even with the emerging scene of black gay men in London, Justin didn’t feel much affinity wit it or have contact with it – indeed when articles honouring his memory are released, gay friends and ex-lovers who provide commentary are nearly exclusively white.[11]

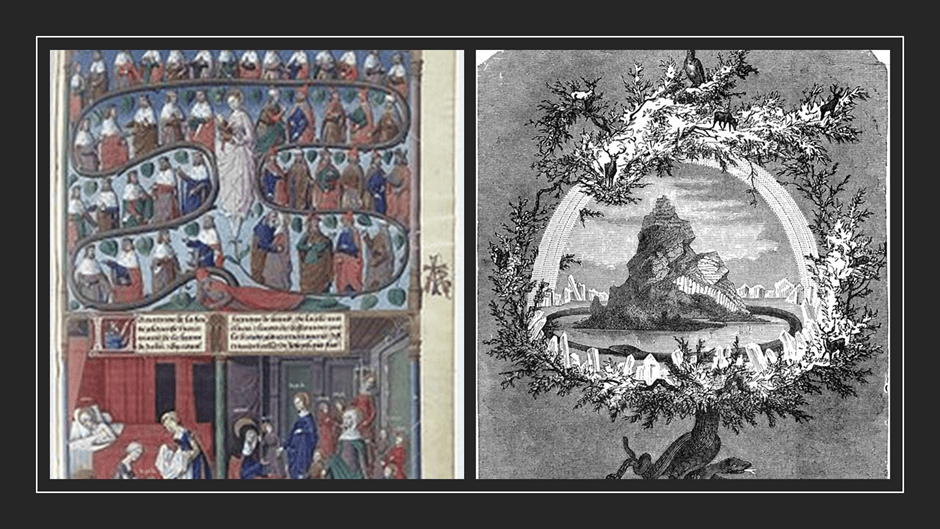

Personally though, though I am not Black, as Donkor is, I keep returning to the warmth I sense in Okundaye. Communities need their myths in order to cohere and to seek a Black lesbian and gay community is a necessary thing, one not reliant on white myth, heteronormative myth And especially white heteronormative renderings of myths often more flexible in mixed-race origins. Community can knit in weird ways. Mark Thompson was the closest friend to Okundaye before the project, and the links he created initiated it, though less with Alex of course, In Mark’s story HIV diagnosis was a big turning point that started before he was himself tested in the chat in a Black gay men’s group at college. From the shock of positive diagnosis he moves into a privatised realm wherein the only question to come to him is ‘who he believes to be the man who infected him’. Yet, having deduced an answer, an older man named Will, he recreates the search into a new myth, a Life-Tree Yggdrasil, or perhaps, but of a Black communal lineage in space and of time.[12] Mark says of Will:

He is more than [just] somebody [who] gave me HIV, a lot more than that – not just “as a human being” but in terms of our lineage as Black gay men. … Si we’ve been here, we have a connection to the past. … There’s something incredibly touching about this reclamation of the epidemiology of HIV as a map of vertical and horizontal relations between queer men, something which rebels against the moralising through which we’re often instructed to view HIV transmission and instead creating a multi-generational family tree.[13]

The Tree of Jesse and the Life-Tree Yggdrasil. Mythic representations of a world order or multi-generational family trees..

There is already a hint here of how and why a local oral historical project such as this has to widen its significance through all the resources available to it – even the transmission of HIV in vertical and horizontal panes through time and space. It even creates myth from the way we can now ‘view generations of Black gay men not only through sexual relations but also the mutual, often hostile environment of this nation, which has shaped us at different points along the timeline of our lives’.[14]

But myths are the stuff of art too and found in even oral art such as life-story telling, as well as music creation or curation (the disc jockey for instance), the curation of social and political spaces, the voicing of communities. But it also includes graphic art, photography, poetry (of which much more later) and even the craft of action research such as this book is: research that aims itself to change that which it studies, whilst it studies it, in order to address its development for the better. One of Okundaye’s interviewees is Dennis Carney, whose lover Trevor Moore died of AIDS in the first terrible tranche of its THEN deadly effect. When he eventually came out as gay to his community he feared would reject him but he knew his sexuality could mean nothing to him without it acknowledging Blackness and his knowledge of the effects of racism, A documentary Blackout was made on the BBC in response to this issue in which Derek appears. In it too Dirg, whom we have already met, reads a poem (in full in the book) which explains to a Black mother that she need not fear a Black gay’s sons choices, because:

For sons who love men like me. Do not feel ashamed for how I live. I chose this tribe of warriors and outlaws.[15]

The recourse to a mythic tribe, with the play on ‘outlaws’ being a recognition of resistance of a state, a white state considered blind to its mores, is part of the mythic reinventions (the ‘tribe of warriors’ for instance speaks to a ‘mythic’ or legendary African past mix of history and invention) I speak about whilst actually directly describing traits of two communities, for both Black and Gay male communities know what it means for their communities to be outlawed in practice, even by ‘stop and search’ 9a very live issue then, as (unfortunately) still now.

But though this line speaks to Dennis, the speaker of the poem on the documentary is Dirg, and in his chapter we have already been told that he was (a fact he rarely shared) one time the partner of the poet Essex Hemphill, whose poem this was, a fact not known to Dennis when earlier he came to read Hemphill, as well as other Black gay writers, at Dirg’s recommendation.[16]

Dirg’s connection to Hemphill was still poorly known when Dirg spoke to Okundaye, but so was the fact that Dirg himself wrote some beautiful poetry. Amongst them, Okundaye quotes one that is central to this book and that I use in my title. Here is the whole first stanza, the rest is in the book:

Deep in thought and Reading works of white men, I am sometimes forced to sift To give my credence, to my people My mind has to rewrite What isn’t there but was.[17]

The whole problem is there. If all history is written by people who have good reason not to know you as ‘your people’ are, then you have to rewrite what to them ‘what isn’t there’ precisely because ‘your people’ know it was. But lacking records means using resources white science considers subjective, inauthentic and invalid (the names it gives to data it will not acknowledge) and it must embrace a liminal identity between fiction and truth. That, I would say (with Sir Philip Sidney and Shelley, is often the route to a deeper truth. But poetry, stories and action research by necessity live on the cusp, even where the identity of interviewer and interviewee is blurred in communally shared myths of origin, truer than white history makes them or omits them.

Even community building needs to generate myths and legends, about which the story of Biggy, the DJ, is clear, whose drive is mixed with what in part Okundaye calls ‘romanticised vision of these scenes’, as elder Biggy remembers times when Black gay male sociality mixed elders with the young, the ‘chicken’. True or not it makes the now elder Biggy smile. But so he does when Okundaye’s draws out the conflictual dramas of these memories, myths even about sex/gender and the complex ‘warrior’ role, called out when anyone ‘called me a bitch’.[18]

The serious version of all that mix of oppression, the elements of self-oppression and the building of a strong honest culture where myths come from lovemaking lies in another Hemphill poem, a superb one called Skin Catch Fire, dedicated to Dennis whom we have already met.

From the details of sex in visceral detail, even along the thigh to the ‘rod of questions’, tjhe whole poem (readable in the book) imagines the firing, from the skin of two Black people touching each other, a ‘power of hope’, ‘sane salvation’ that is a city alight in myth. It may be Sodom scoured by God but it rises again:

Like a city, A phoenix, a pyromantic.

The term ‘pyromantic’ is not a neologism (although the embedding of the word ‘romantic’ is important in this bodily sex poem), it refers to the ancient ritual of divination by fire, and that can include how God punished Sodom and Gomorrah but it is juxtaposed to a fire myth of renewal, the phoenix.

There is more to say about art, mythmaking and the roots of both even in as unromanticised communities as Brixton. The ways of making them are many. Ajamu X does it through photographs, which many Black queer men thought to be unrepresentative, and lacking positivity. Yet this artist, from my home town of Huddersfield, felt that his images created myths to counter more potent myths in the Black community too, of an overwhelming and violent masculinity, but of that we should be aware too of compounding white racist myths. What Ajamu insists on that some attempts of Black communities to find only ‘positive images’ is ‘reactionary bollocks’.

And that’s my problem with some of your Black gay politics, because it’s actually conservative politics. I think there is a danger if Black gay men are telling other Black gay men how they should live their lives.

And so what now, quid tum? [19]. Myth must inform and test other myth and only ones of value to real lives survive (goodbye racism! Perhaps) but there will still be multiple myths. Communities that embrace diversity have to embrace wide differences of how the community is structured, and in the end these are better structured loosely, like the flames shooting from the burning and renewing phoenix.

This is a great book. Buy it. Read it. It is a delight.

And yes, it will tell us how to manage the good things that make our lives of value, even to white people like me, for whom looking in means finding ways of changing white community for the better, before deeper admixture of communities is fully possible. Before that we must learn about each other, mix when it is consensual on both sides and love stories we did not know before.

All my love

Steven

xxx

[1] Jason Okundaye (2024: xi) Revolutionary Acts: Love & Brotherhood in Black Gay Britain, London, Faber & Faber

[2] Ibid; 250

[3] Cited ibid: 45

[4] Lanre Bakare (2024) ‘Revolutionary Acts by Jason Okundaye review – bringing Black gay history to life’ in The Guardian(Thu 29 Feb 2024 07.30 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/feb/29/revolutionary-acts-by-jason-okundaye-review-bringing-black-gay-history-to-life

[5] Ibid: 7

[6] Michael Donkor (2024) ‘Revolutionary Acts by Jason Okundaye review: As a Black gay man, this stunned me’ in the i newspaper online (February 22, 2024, 3:16 pm(Updated February 23, 2024, 9:37 am). Available at: https://inews.co.uk/culture/books/revolutionary-acts-jason-okundaye-review-black-gay-man-stunned-2914444

[7] Ibid: 245

[8] Ibid: 227ff.

[9] Ibid: 71

[10] Ibid: 74

[11] Ibid: 88

[12] Ibid, 139f, 143f. respectively

[13] Ibid: 144

[14] Ibid: 144

[15] From Essex Hemphill Conditions XXIII, cited in full ibid: 172

[16] Ibid: 164

[17] Cited ibid: 45

[18] Ibid: 109

[19] https://livesteven.com/2024/04/26/quid-tum-what-next-so-what/