Olivia Laing tells us as her book The Garden Against Time closes that she loves a line from the fourteenth-century Psalter by Richard Rolle: This boke is cald garden closed, wel enseled, paradyse full of appils’. In contrast she goes on to say that her ‘book is a garden opened and spilling over. The common paradise, that heretical dream’.[1] This is a blog that reflects on Olivia Laing (2024) The Garden Against Time: In Search of A Common Paradise, London, Picador.

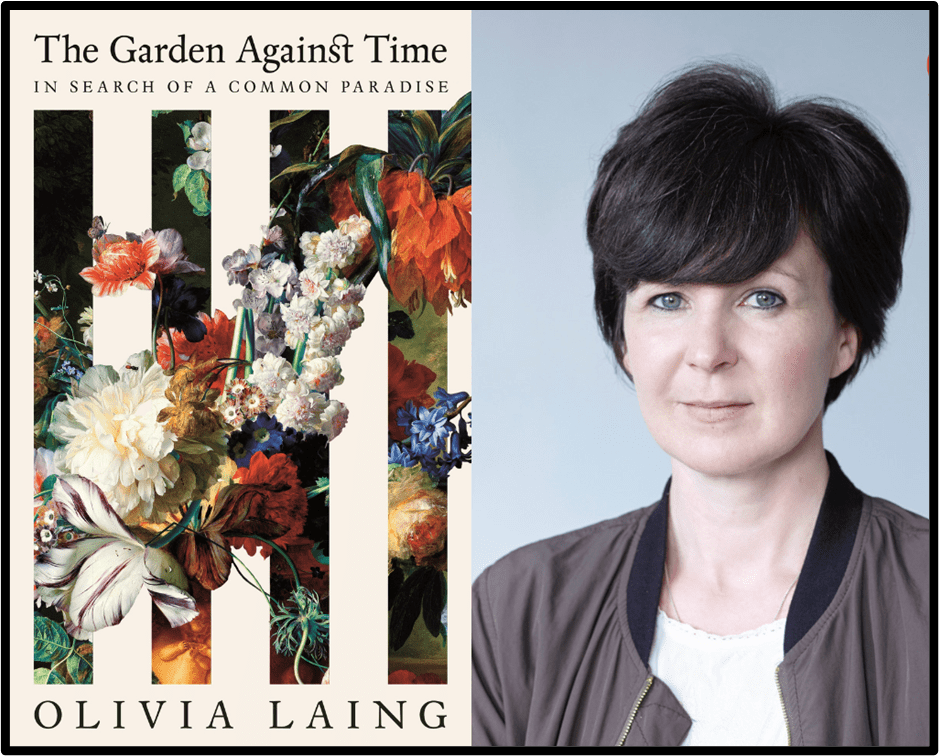

Olivia Laing’s garden and, on the right, Olivia in her garden.

We think we know what it means to open a book, usually in preparation for reading it and to close it when we end it, or pause in our reading or abandon it as ‘not for me’. But some books seem in their words to boast (or at the least accept the case) at the idea of being unreadable for some but an élite audience. In Book 7 of Paradise Lost Milton thanks his muse Urania for staying with him in the dark days of his blindness and political danger, as a republican amongst Philistines, in this manner:

….while thou Visit'st my slumbers Nightly, or when Morn Purples the East: still govern thou my Song, Urania, and fit audience find, though few.

To be fair Milton does not refer to the difficulty associated with his verse, full of obscure learning and reference and strained Latinate forms of English full of Miltonic neologisms, some think, but to the fact that in the restored state of the monarchy he had become persona non grata for those who wished to be at the centre of political debate and state honours. Yet some books can be called enclosed and sealed because they resist being read by those considered not in some way ‘fit’ or equipped to read them, because of the nature of both the knowledge, forms of language and accessibility to other than the reader qualified to read it (by education, intelligence or imaginative capacity). Those, for instance, who feel they have mastered James Joyce’s Ulysses sometime gratefully closed his later novel Finnegan’s Wake soon after opening it. Being difficult once meant using a method, as in Spenser’s introduction to his The Faerie Queene, written to Sir Walter Raleigh, another ‘School of the Night’ poet using the same method in his exquisite difficult poem The Ocean’s Love to Cynthia, which he named as ‘being a continued Allegorie, or darke conceit’. To be ‘darke’ meant you would be difficult to understand in full, as is the mundane world where we see the truth of the divine in a glass darkly according to Saint Paul (I Corinthians 13: 12). Hence the darkness embraced by the Christian Psalter, which its English author, Richard Rolle, calls in a favourite line of Olivia Laing’s, ‘closed, wel enseled’. Of course, the book is only called (‘cald’) these things in terms of its metaphoric metamorphosis into ‘a garden’. Yet again dark allegory is present in this ‘garden’ reference; the reference being to Song of Solomon or Song of Songs. Here is the text (King James’ Version) of verses 7 – 13, the verse referred to by Rolle being verse 12.

7 Thou art all fair, my love; there is no spot in thee.

8 Come with me from Lebanon, my spouse, with me from Lebanon: look from the top of Amana, from the top of Shenir and Hermon, from the lions’ dens, from the mountains of the leopards.

9 Thou hast ravished my heart, my sister, my spouse; thou hast ravished my heart with one of thine eyes, with one chain of thy neck.

10 How fair is thy love, my sister, my spouse! how much better is thy love than wine! and the smell of thine ointments than all spices!

11 Thy lips, O my spouse, drop as the honeycomb: honey and milk are under thy tongue; and the smell of thy garments is like the smell of Lebanon.

12 A garden inclosed is my sister, my spouse; a spring shut up, a fountain sealed.

13 Thy plants are an orchard of pomegranates, with pleasant fruits; camphire, with spikenard,

14 Spikenard and saffron; calamus and cinnamon, with all trees of frankincense; myrrh and aloes, with all the chief spices:

15 A fountain of gardens, a well of living waters, and streams from Lebanon.

A. S Byatt says of verse 12: ‘There is something immediately powerful, in most cultures, I should think, about the virginal images: …’.[2] She, of course, also uses it as the title of the first of her Frederika Quartet of novels, The Virgin in the Garden. She does this both to exploit the imagery of the Song of Songs and because of the link Spenser, and others in the informal ‘School of the Night’ poetic group, established between that Biblical book and the praise of the Virgin Queen, Elizabeth I. The Virgin in the Garden is set in 1953 on the accession of Elizabeth II, which itself revived some of that ‘dark’ imagery.

Byatt is superb in her essay on the Song of Songs however in explaining how the early Christian Church robbed it of its eroticism; in, for instance, the language of ravishment the male lyricist projects onto his virgin spouse as a fertile sensual garden. The Church allegorists interpreted that garden as itself a dark allegory of the initiated Christian’s love of the pure Church and, with it, renunciation of the very visceral sexuality it invokes. In Jude the Obscure, Hardy has Sue Bridehead (a sexually resistant woman with the name of the unbroken hymen) rehearse that very argument. Byatt explains that the source of the imagery may well invoke the ‘sacred prostitution’, as believed by ‘modern scholars’ who find in it ‘an echo of something more ancient’ than both Judaism and Christianity’s appropriations of Judaism; ‘the marriage songs of the sacred marriages of the ancient Mesopotamian gods and goddesses, Inana and Dumuzi, Ishtar and Tammuz’, often incestuous marriages.[3] The language of enclosure and sealing was thence used to talk of literature itself as containing hidden secret codes and meanings only available to the initiate. This is part and parcel of the history of both realised enclosed gardens in cottages, Bishop’s Palaces and Parks (the one in Bishop Auckland is just reopening in revived state this year) or mansions.

Olivia Laing is well aware of enclosed gardens, in literature, the lives of those with homes and gardens and in her own new home with her new husband, poet Ian Patterson. Her approach is to open up words that otherwise silently enclose and secrete the facts of how our own oppressive society structures exclusions of the marginalised and sometimes more actively oppresses them. She opens up meanings hidden in supposedly innocent words used of gardening projects and innovations. She finds whole histories of social exclusion, marginalisation and oppression in the discourse of the most literally physically ‘open’ of gardens – the landscape gardens fashioned by Capability Brown. For landscape is an imposition on ‘nature’ not of some natural referent. As she shows, the word originates in artists including land ‘improvers’ in the eighteenth century. Rich landowners destroyed whole villages or removed the cottages of labourers in the interests of the ‘picturesque’ view’ attained in their absence; as theorised by, for instance, Uvedale Price.

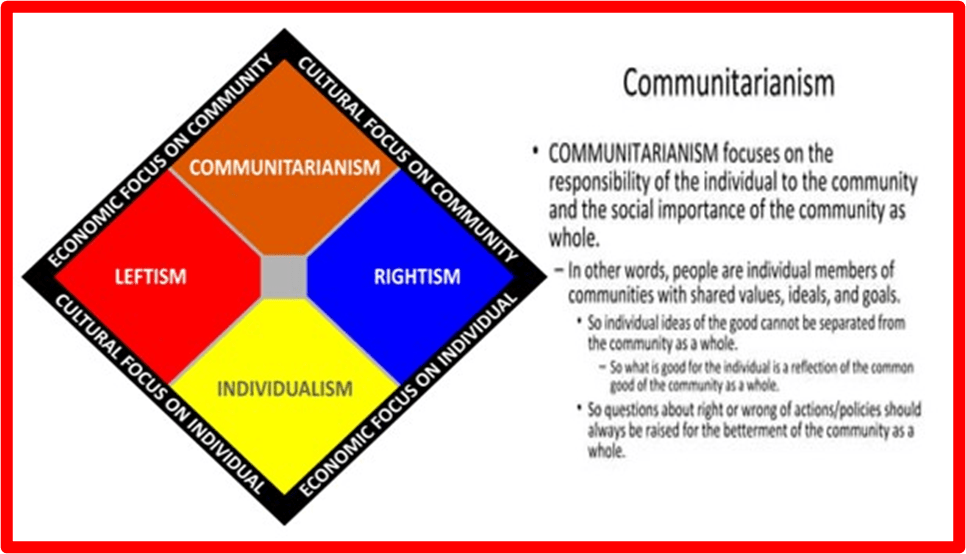

This was only one way in which common land was privatised and ‘enclosed’, aided by Government Enclosure Acts’ supposedly in the interests of agricultural improvement but certainly to the cost of the poor and their rights to land on which to make a living. It lay at the root of the dispossession from a home which in many ways were triggers that led the poet John Clare to his own ‘enclosure’, in an asylum, and likewise to him being locked from the canon of literature till well after his death. Kathryn Hughes in her review of the book in The Guardian focuses on this theme, though I feel her own language to some extent de-radicalises Laing’s approach with no mention of the books advocacy through its stories of forms of English ideas of a Commonwealth or of Communitarism. Why exclude, for instance, the way in which William Morris understood Marx’s Communism, an understanding that also lies in forgotten rural thinkers too like Goodwyn Barmby (born in 1820 in the village Laing later lived in). Barmby was a Chartist and eventually an idealist but unthreatening Unitarian preacher. Hughes recognises the politics of the book thus:

But just at the point where she seems in danger of disappearing into a private dreamscape, Laing pulls up sharply to remind us that a garden, no matter how seemingly paradisical, can never be a failsafe sanctuary from the brutish world. It always arrives tangled in the political, economic and social conditions of its own making.[4]

The approach here is too cosy and comfortable a rendering of some of the urgencies of Olivia Laing’s politics in every area where social phenomena, like the reframing of nature in the interest of human pleasure, leisure and appreciation of beauty, are politicised. I can’t see Laing as suddenly ‘pulling up’, as if she slammed the brakes on her Mercedes, for politics is never but waiting to be exposed from its hiding place in the dark sites of ideological naming wherein it hides. I have mentioned already how Laing unpacks the word ‘Landscape’ to show that it is a word hiding oppressive practices playing to the interests of a landed oligarchy in the Agricultural Revolution, and eventually to the interests of the bourgeois capitalist adventurers of the Industrial Revolution, soaking up the cheap labour released from common land ownership.

I don’t sense Laing ever ‘losing herself in a ‘dreamscape’. Her point about Milton’s Paradise is not mainly that it appropriates the linguistic forms of nations subjected to European imperialism and colonisation in order to describe Paradise, which he does and Laing notices. She unpacks the terms ‘Plantation’ and ‘Planter’ and the oppressive horrors underlying the relationship to the gardening of souls. Those associations are even explored in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. That Paradise or Eden are not merely ‘dreams’ (except for the right-wing believers in an entirely cognitive theory of beauty and the woolly-minded Guardian ‘individualist’ left) but things you have to work at making and then forever continue to work at in order to maintain them as paradisaical. The work does not involve the use of the weapons of an over-powerful hierarchy of leaders under one Supremo, like Stalin or Milton’s God (whom Laing reads as William Empson does in his Milton’s God). Even though they live in Eden, Adam and Eve WORK. Laing says of Milton that:

He used the model of horticultural cultivation as a way of considering good government, right relationship between different kinds of beings. Eden runs on very different principles to the autocratic rule of heaven. If God lays down laws and punishes transgressions, Adam and Eve practise a style of custodianship that is understated and benign. When they prop a rose or twist a vine into an elm, they are active collaborators in an interconnected ecology, subtly stage-managing processes that are already underway in order to maximise abundance and pleasure. / …The garden serves as a kind of lodestar, an experience of nurture and richness that cannot be dismantled and might in the future be recreated. …[5]

The person who wrote that and who praised even people who failed to maintain a Communitarian dream they one believed in and practised, like Goodwyn Barmby and John Clare, and served as its martyrs (since brought low in one way or another by the status quo) are all part of the pattern that sustained William Morris’ lifelong socialism. Laing is not, I’d insist, just a privileged white woman (though of course she is that – the world is one of constant contradiction) but a seasoned political commentator and activist of a kind, continually unearthing the ideology that the status quo passes off as being ‘nature’ and ‘natural’. She set out to do that rather than being reminded of it as she (in Voltairean fashion and with the same thinking I would say) whilst doing so, cultivated her garden. For all of us, of course, il faut cultiver notre jardin.

Her final words cited in my title for this blog make that clear. Where the status quo creates moments that close up (‘inclose’ sic.) and ‘seal’ the truth in a box, like an enclosed garden, ‘this book’ (her book) instead ‘is a garden opened and spilling over. The common paradise, that heretical dream’. Because a Paradise that is just the few for the elect and/or the entitled is no paradise. This is true of the great landscape gardens created by Capability Brown (or Shrubland Hall that she analyses, for she is a near neighbour of that mansion in her house with a walled garden) . They too are a ‘paradise’ ONLY for a privileged class that guides its right from political threats to it. Shrubland Hall was created on Capability Brown’s pattern or mode, with its ‘ha-ha’ so that its lands are made look more extensive to the eye, whilst also providing, a a ha-ha must, a means of laughing (ha-ha!) at the unsightly poor expelled from those lands.

Unlike the Psalter writer, Rolle, whose aim is for a liturgy that works alone whilst in a church and is not extended in meaning beyond the church’s walls, Laing wants to open up the abundant wealth of beauty to the ‘many’, to the ‘commons’ and common, like Barmby, John Clare and William Morris in News from Nowhere. The rub is the true political radical, such as Milton, is a beautiful experience hidden by the canon’s aim for a established and establishment ‘English Literature’ that is not for the many. A canon is like an oppressive form of the garden with the ‘common’ selected or weeded out of it: to weed in this sense is to pull out the rotting root, the true radical in reality including them only amongst neglected writers, known only to specialist academics now, that were often champions of the ‘common’ and art for the common in their own time (like Morris). Laing’s empathy for Milton hiding from the retribution of the restored Stuart Monarchy under Charles II is wonderful to read. Her implicit sorrow at the desecration of Milton’s corpse where ‘for two days people raided the grave, wrenching out his hair and teeth to sell as relics’, is telling of how the English literary establishment, supposed admirers of a great English poet and tradition, uproots Milton’s radicalism, replacing it with relic worship. Hughes’ take on Laing’s book is too comfortable suggesting an Olivia Laing robbed too of her very clear radical political bite, other than that the bite of ‘centrist’ Guardian journalism.

Perhaps in one way, her book, in praise of her own restored ‘garden enclosed’, is in that closed tradition of literature too. It has constant recourse to classical as well as less know texts, but even to the Song of Songs. However, if it is so, it is only in the spirit of opening up those closed-down references to new readerships and to more radical reading. Texts come to blossom anew in the air of a more common, and communal, understanding. That is, as we shall see, her approach to suppressed traditions of queer life; seeing us as members of a suppressed communal life, shut out from the mainstream commons for too long. Indeed the very garden Laing restores was restored before from an older pattern first by the deceased Mark Rumary, author of The Englishman’s Garden and once employed at that queer relic (lauded in Virginia Woolf’s equally queer classic Orlando), Vita Sackville-West’s Sissinghurst Castle Gardens. She says of him: ‘Gay and closeted, a language I know from my own childhood in a gay family in the 1980s’. I think the attitude to queer lives definitive of the book and its politics: sexual, domestic, social, national and otherwise. To be ‘in search of a COMMON Paradise’ is a psychosocial and communal quest, for otherwise it hides under the ideology and power of the hierarchical status quo.

I did note as I wrote this piece that some reviews of the book praise it in ways that are less closeted than Hughes’ otherwise admiring review. Hannah Silver, for the online magazine, Wallpaper actually interviewed Laing herself, who tells it as it is. She quotes this gutsy statement:

“One of the things that I really wanted to explore is the ways that gardens look really benign – they don’t look like a statue of a slave owner,’ adds Laing. ‘But they’ve got all of these hidden relationships with colonialism, and with enclosure. They’re a place that people have used to basically launder their money, burnish their reputations, rise up the class ladders. The tradition of grand garden making is pretty shady. But at the same time, the garden can be this really radical place, there are queer gardens that have been sites of sanctuary, there have been gardens in wartime which can be amazing refuges. So I wanted to lay out the truth about what gardens can be; in a more negative sense, but also pack it with these stories about gardens as antidotes to messed up capitalism”.

Kathryn Hughes never mentions the queer content of the book, even in reference to Mark Rumary, whom she pushes back into his Englishman’s closet. The ‘anecdotes of messed-up capitalism’ also just aren’t pushed in the review in the context of an activism set against them, even really when retailing references to Derek Jarman, whose politics of protest had wide reference, as Laing explores. And her reference is cogent and strong and in the left tradition rather than the ‘great tradition’ of the English literary inward-looking. Silver quotes Laing again, including this:

“It’s not just the individual bloom that you’re gardening for. It’s the whole system that’s making it, and shifting into that kind of network thinking is very vital, while we’re thinking about climate change. It’s not about the individual, it’s about the whole community, and the whole community’s health and vibrancy, so I found it quite a radical education, really learning to garden”. [6]

This is about opening up and spilling over abundance of thinking, feeling and urgency of action based in hidden traditions or readings of works that are often thought to be oppressive; merely of appeal to scholars. It is a view unhappy with and hermetic enclosed literatures for ‘the few’ rather than ‘the many’. It exposes by looking and reading more closely neglected and misread works (and works about the work of gardening) those ‘hidden relationships with colonialism, and with enclosure’, the ruses of the imperialist and rentier classes. And despite Laing’s beautiful writing (which some think elitist because they do not know of the learning aspirations of those systematically excluded from the power of education to create change), it champions what is ‘common’, that which isn’t spending all its time preening itself for consumption by a ‘fit audience’, by which they mean a refined or ‘uncommon’ audience. The many love beauty too. Of course, as always, being a proudly common sort of guy, I hide Olivia Laing’s superbly honed nuance in every realm – of writing, politics and almost certainly gardening (I have never cultivated a garden as my husband will tell you). Her material on Iris Origo and the transformation of a Fascist sympathiser like her (whom was liked and revered by Mussolini, Il Duce) to a hero of resistance to Fascism and collaborator with Allied Forces is wonderful, as is its connection to gardens. Her finding of authority in difficult writers stuns – writers like Sebald, especially The Rings of Saturn, for instance.

The true subject of the novel, of course, is time – how we see and construct not only the present but the past and the future. In the end the nature of our politics and our orientation to art stems from such things like these. If we imagine things lost, like Paradise is lost, we think it cannot be regained and we will think like a reactionary. If we see any idea of positive change as unachievable utopianism, it will have a similar effect on our outlooks. Even words like landscape and plantation can be redeemed and re-imagined as Laing shows us that Derek Jarman’s Modern Nature did. And if we think that the need for refreshment and recreation is a privilege for the already privileged, our fate is the worst for paradise ought to be a space, like Milton’s Eden for both rest, recreation (even the open sexuality which Adam talks about with the queer angels) as well as work. Work is not the consequence of the Fall. Its horrors are the fault of unequal and unjust distributions of resources. Even in a Communitarian community we require refuge and asylum and William Morris knew that well.

However, for me, this book as with Olivia Laing’s other queer-allied works (she is the exemplum of the queer ally to me in writing). It is not only that she points out that queer life was always ubiquitous but also penetrates its links, especially in artists, to communities with gardens such as Cedric Morris and Arthur Letts-Haines at Benton End, where they created endless Benton variegations of common breeds of flowers.[7] It allows her to excoriate the oppressiveness of a heteronormative and homophobic state, showing how and why in particular the sanctuary of Benton End existed.[8] Mark Rumary’s garden and partnership with a man he always ‘had’ to call only his ‘friend’ is another such compromised but necessary sanctuary. Derek Jarman’s life illustrates why his Dungeness garden is significant as a means of hoping for a renewed and juster future, in a shareable abundance of pleasure not austerity. His Modern Nature is a manual for constructing’ a device, from the ways and means of being a gardener, for managing not only personal but social, global and ecological trauma. It had to be sited near to a nuclear plant therefore, in a place not famed for its suitability for gardens, the ‘shingle beach at Dungeness; and started ‘after he had been diagnosed HIV-positive’: then a prognosis of death as a certain near future. Laing says:

It arrived in my life in 1991, bang on time, emerging out of the same desolating set of circumstances – Thatcherism, now congealing into the cricket and warm beer nostalgia of John Major; the Aids crisis, ten years without a cure or even reliable treatment; and section 28, with its spiteful delegitimisation of the gay family. ….[9]

Mark Rumary was, as his solicitor said, ‘gay when it was not good to be gay’. And that time recalls the story of her own upbringing in a ‘gay family’, about which:

It’s not hard to articulate what was so wrong with those years, the second, unchildish half of my childhood. We were out of place, definitively strange. Two adult women, two small girls did not constitute a family in those relentlessly homophobic years. The house we landed in was made dangerous by alcohol, periodically illuminated by flashing blue lights. I remember it with a clenched feeling: freezing at the sound of a raised voice, trying to soothe or pacify, though it can hardly have been my job.[10]

The cusp between alienation, marginalisation and personal lives touched by alcohol and ruined by it has been Laing’s theme before but here the personal motivation is clearer; the reason why the personal is political being urgently conveyed in unsaid links that are clear in other stories told of other people in the book. The COVID pandemic too created this needs for islands of security where personal agency shown in work created at least the ‘evidence of time proceeding as it was meant to, seeds unfurling, buds breaking, daffodils pushing through the soil; a covenant of how the world should be and might again. Planting was a way of investing in the future’.[11] Here, we see how ambivalent are the human needs to ‘invest’ and ‘plant’ for our own future, when they are selfishly conducted. Human beings created by ‘investment’ of excess a greedy self-centred capitalism, and Plantations likewise on which slaves die to profit the entitled. The book ends, as does Paradise Lost, with an ‘Expelling Angel’ (the name of the last chapter). But when a good book closes (and has to be closed) if it is really good it remains OPEN and bounteous, promising future-ward new ways of practising communitarianism. As early as Chapter II’s ending, we hear this in the end of Laing’s analysis of Paradise Lost, read for the first time by her and in a way she describes as the ‘labour or the thrill of reading’ it. Where Adam and Eve’s spend their days cutting back the ‘growth, lavish, excessive, wanton, intransigent’ they feel like they use time in ways ‘a lot like mine’.[12] But their ends (their aims and purpose) are the same too. Here is the chapter-end about an epic poem ending: ‘The final line swells with possibility. “The World was all before them.” Whatever they have suffered, whatever damage has been done, the future lies open ahead‘.[13]

If you start a blog about closed books, you should end with the fact that sometimes closure predicts an opening up. I read literature I think more like Olivia Laing most of my life than in ways encouraged by the closed-in training of the educational establishments that they thought was an academic education. You ought to read for what is commonly shareable in the end – the labour, the thrill and the hope that has the foregoing necessities, like work, behind it and supporting it. The future should be a search for a communitarian ‘common paradise’, not a way to keep the entitled in their excessive wasteful gardens that look open but are enclosed by ‘ha-ha’s’; the mocking laughter of the privileged who will do anything to stay as such.

Do read this brilliant book

Love Steven xxxxxx

[1] Olivia Laing (2024: 289) The Garden Against Time: In Search of A Common Paradise, London, Picador

[2] A.S. Byatt (2005: 166) ‘The Song of Solomon’ in Jamie Byng (Ed.) revelations: Personal Responses to the Books of the Bible, Edinburgh, Canongate, 157 – 169.

[3] Ibid: 164.

[4] Kathryn Hughes (2024: 46) ‘This other Eden’ in The Guardian (Sat. 04.05.24), 46.

[5] Olivia Laing, op.cit: 55f.

[6] Cited: Hannah Silver (2024) ‘They all have hidden relationships with colonialism and enclosure’: Olivia Laing’s new book considers the garden’ in Wallpaper (online magazine). Available at: https://www.wallpaper.com/art/olivia-laing-book-the-garden-against-time

[7] Ibid: 210ff.

[8] Ibid: 212 ff.

[9] Ibid: 196f.

[10] Ibid: 193

[11] Ibid: 11

[12] Ibid: 41, 44 respectively

[13] ibid: 56.

Beautiful.

LikeLike