Who would you like to talk to soon?

I wrote and put online the blog below on he 24th May. John Burnside died on the 29th May, announced by his publisher on 31st May. Never to see the hero again and talk to him, even if at a book signing. I mourn for him, his family and ALL OF US.

Text of the original blog below:

________________________________________________________________________

Yesterday, amid the noise of the stress, we sat for a moment in Waterstones with a coffee and I perused the poetry shelves, finding, to my delight, a volume of John Burnside, that came out earlier this year, that I had neglected to purchase. I bought it and read it avidly that evening for the first time.

Reading Burnside has always seemed to me to talk with, not ‘talk to’ or even ‘listen to’, a genuine person – for the experience feels like participation rather than like a one-sided monologue for either partner. It involves more than him or me in the transaction. There seems a third something speaking, listening, and silently being with us throughout that interaction. Perhaps it is not, anyway, just ‘something’ but ‘everything’ that matters there with us in those poems. I want to commune with this soon. Who could not feel this?

After I read it for the first time, I knew one reading was not enough. I jotted down my thoughts in an online ‘review’, with my first impressions. Here it is below:

A stunning collection takes the poet back and forth from the deepest depths of that which must not be remembered to the search for truth that might lie precisely in areas of your life that resist such revisiting. These poems are truly metaphysical and yet true to the awakened senses. The tremendous sequence ‘Bedlam Variations ‘ is like Maud written with the insight got from a post-religio-cultural epiphany. A great poet.

Why did I reference Tennyson’s Maud? I don’t think I was thinking of the whole poem,[you can read it online here https://www.gutenberg.org/files/56913/56913-h/56913-h.htm%5D, but of the reflective narrator weaving into his present life-drama terrible memories mixed with fierce and urgent desires:

1.

O! Let the solid ground

Not fail beneath my feet

Before my life has found

What some have found so sweet;

Then let come what come may,

What matter if I go mad,

I shall have had my day.

2.

Let the sweet heavens endure,

Not close and darken above me

Before I am quite quite sure

That there is one to love me;

Then let come what come may

To a life that has been so sad,

I shall have had my day.

That voice is not like Burnside’s at all. Tennyson’s narrator has not the metaphysical knowledge and feeling that strikes much deeper than the poor imitation of Hamlet in this’Mondrama’ (Tennyson’s terminology). I couldn’t stop thinking and writing on the volume by Burnside that evening: writing about the effect of the poems on me and their relationship to the thought embedded in the repertoire of selected human history and myth it uses. I am away in Glasgow with no Internet connection at the flat and wrote it in Word. I could only photograph the words to include them here.

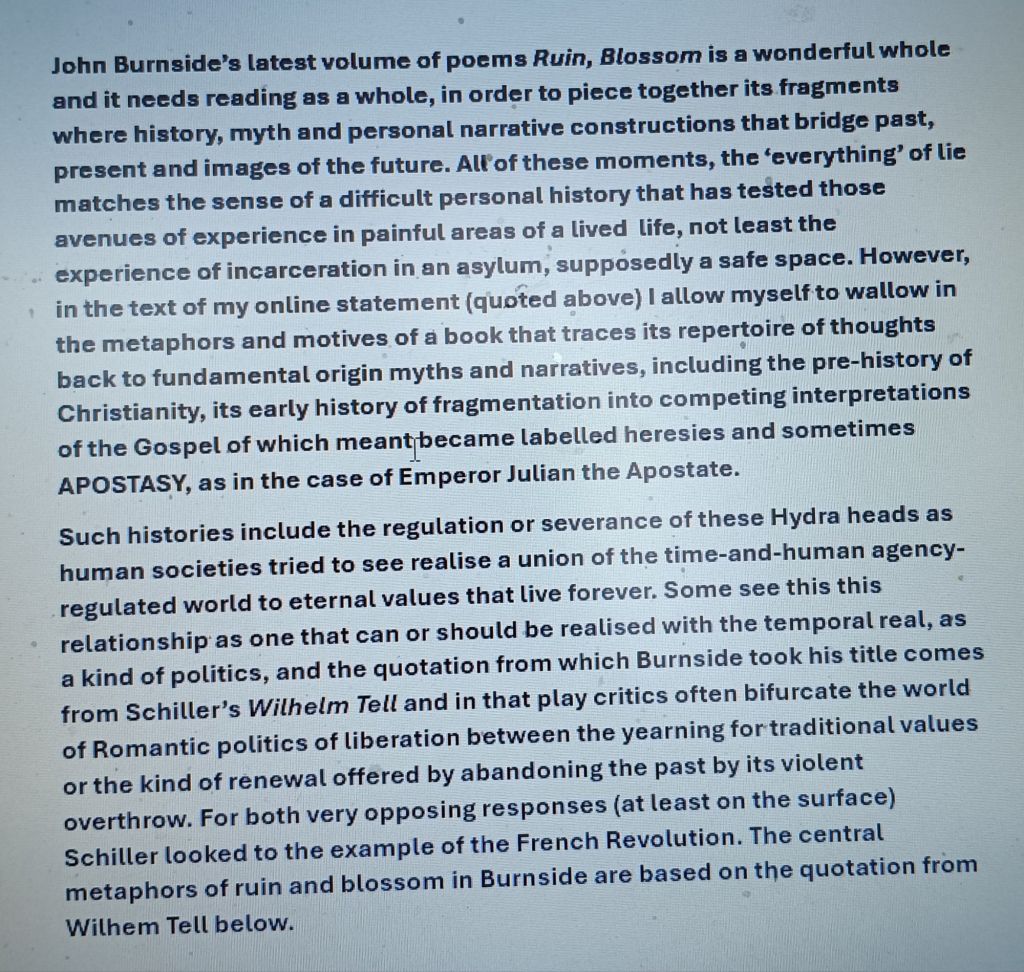

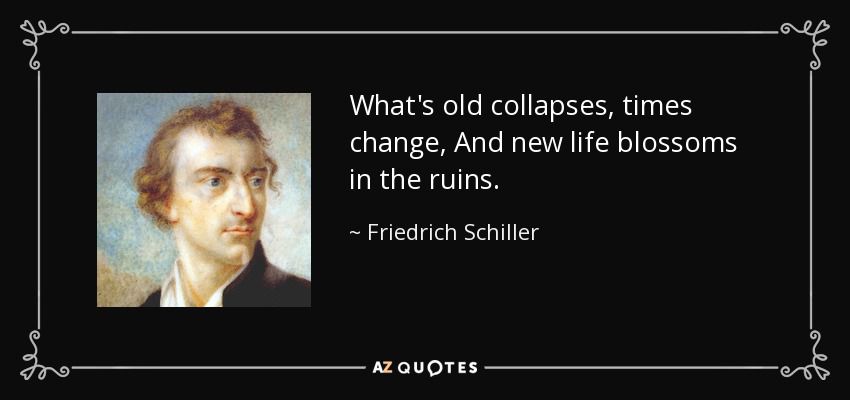

What’s old collapses, times change, and new life blossoms in the ruins.

— Friedrich Schiller

In Ruin, Blossom Burnside organises the poems into 3 subsections: APOSTASY, ASYLUM, and BLOSSOM. All relate to moments in personal and global narratives fo the search for enduring meaning – for what defines eternity if possible – outside the relentless onward linear of progression to endings in the experience of mundane TIME. Cyclical time – that of seasonal death and recovery (or resurrection) – is clearly there in the poems too, but so beautifully modulated because ‘ruin’ has to be as gratefully accepted as blossoms of renewal.

The central section of the book depends on both the hopeful and the sad histories of the word ASYLUM: a place of sanctuary from acknowledgement of an old self hiding in the hope of something new emerging, and its decline as a word into the name of an horrifying institution. Yet even that institution has its place in compressing horror into hope in the book as a whole. This middle section includes a wonderful 10 part sequence of sonnets, some partial in their form, called ‘Bedlam Variations’, after the most notorious of the historic asylums.

The book deserves a fuller treatment, but here I want to concentrate merely on the joy and pain of speaking with the poetic mind through that one part-work.

It concerns a male narrator-lyricist like Maud. On the ward of his asylum, the lyric narrator dreams of gestures and postures that get implicated in time: to turn back is to go into the past, to look outward is a venture into the present blurring as the present does into future perspectives. For instance, he becomes a boy again, prompted by his study of a well-known book of his childhood:

Alone on the ward, I leave the windows

open, so the bees can come and go,

and turn back to my Boy's Own Book of Birds,

saying the names aloud, to keep them true,

till, word by word, with ruin in my head,

I fold into the light, and I am blossom.

Bedlam Variations II, lls. 9 - 14, page 27.

I love the way the sharing of bee sociality and human aloneness collide here, how turning your back on the ‘open’ vista leads to one’s own past, yoor Boy’s Own past. These lines are followed by the reference to the lines from Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell I have already cited. Ruined civilizations of the past, the old, merge into the ruined mind of an individual after breakdown looking, through an asylum window, for the same blossom that makes things look, and hopefully become, new socially, institutionally and personally; discarding the evils of the past.

The hope in the poems battles with the sense, and this is in Maud too, with the lyric- narrator’s need of renewal because to him he is, or might as well be, dead already before the death of his physical body. It is a state the poem calls ‘posthumous,’: ‘How will the posthumous survive, …?’. [Ibid I, l. 1, p. 26.]. The posthumous look to ridiculous texts from the past, ‘ from fieldguides and the Book of Common Prayer’ [l. 3] and to accustomed escapes from stress, even Bedlam, to find new direction but find only :

that absence, like a sinkhole in the light,

where anything might fail: a bird, a star.

lls. 13f.

We look to the past of centuries like the earlier poems of apostasy that delight to be free of suppised divine guidance of elders. That freedom felt like all that seemed important, but it is not better than the held-in-the-past feel.of a psychiatric ward, eating Empire Biscuits with milky tea, ‘swaddled I the beauty of Largactil/ waiting for Mrs Miniver …’. [V, lls2 -6].

Sometimes I mourn mad gladness, we travrse in our mind the Silk Road to the Orient to ancient Empires [VII], at other times – in the very next sonnet, we go so far back that the world is prelapsarian in the Judaeo-Christiam sens and you undergo the temptation of Eve again:

Before the fall, the woods were full of clues,

but nonone saw the beauty of the serpent,

only the dew trails winding through the grass

wher god had been, before he came to naught.

VIII, lls. 1 - 4

In a world where God or gods are naught, it is not for anyone – not even a poet – to replace them – however much they play at martyrs, a beautiful coinage for the self-immolation of poets. Poets can only point to the contingent beauty they, like everyone else is human guise seem intent on destroying in pursuit of the things of time: growth, progress, and all other future tending myths of perfection to become. So what happens if the ‘posthumous’ return. This is ghe theme of the last sonnet. It gives no hope but a beauty in the double-edged paint and beauty of bruised experience:

If they return, the posthumous will be

as tender as a bruise, run under icy

water, unemcumbered by the weight

of seasons no one else

has witnessed, something animal behind

each gesture, though I thought they would have paled

to nothing, having learned

to hold their peace.

X, lls. 1 - 8, p. 35.

The sum of experience of all forms of asylum, even in the Bedlam of poets, is that poets uniquely witness that wonder in life, which speaks only in silent gaps between noise. That silence IS the peace you hold (a dead metaphor even is revived here). In the end, poetry lives in such wordy evocation of wordlessness, non- sonority of sound, and the invisibility of that to be displayed to others. Thus, the poem ends, with the poet dedicating himself to those who ‘still remain’ who, with his insight, have:

..., come to light

as glitches in the fabric,all

the shadows in a looking-glass that seem

familiar: seen things, forged from things not seen.

X, lls. 12 - 14, p. 35

All of this speaks not only beautifully as Shelley might, but also in the shadow of Saint Paul, the whole book being a human deconstruction of the prophetic verse of 2 Corinthians 18, which provides the epigram for this sonnet sequence:

18 While we look not at the things which are seen, but at the things which are not seen: for the things which are seen are temporal; but the things which are not seen are eternal.

This search from that unseen behind the seen may be the goal of both religion and poetry. Sometimes, though, seers die in the process of visiting the Underworld and find posthumous status before they die. These poets strike out from their asylums and startle us, though they sometimes return to us as if from the dead with news they can barely tell us in the passing words of conversation.

So I may never talk to such poets, whether soon or too late, but between their lines, in the variation of their iambic pentameter length (sometimes to tetrameters – there are examples above), I will hear the burden of their silent volubility. I will have to be satisfied with a silent and nealy sacred communion.

All my love

Steven xxxxx

3 thoughts on “Poetry is a dialogue with everything. The sooner we do that, the better. Communing with John Burnside’s latest volume, ‘Ruin Blossom’.”