Of course, having been born in 1954 and schooled in the sixties, I remember that time. My first computer was an early Amstrad bought in the 1990s. Even in the 1970s, I was subnitting essays at UCL in my own handwriting and using real books in real libraries. We now call that using hard copies. That fact seems to be a decline in itself. However, I am not an antagonist of the digital age. It is clear that it was, for some time, an engine for positive change. I completed an MA course on Open and Distance Learning with the Open University, and I still value the positives I gained from it.

However, there is only one conclusion to draw about the Internet in general. That is that it is a powerful force of influence on how we communicate together and express both our individual and group social identities for both good and genuine evil. Hence, I do remember that period, but to answer that question broadly is too much to do. Instead, I want to look at one trivial example of how invisible power is exercised through control of algorithms that framework invisible constraints and change the nature of debate, often in the name of openness.

O wonder!/ How many nasty meanings are there here!/ How sad Twitter persons are! ‘That grim new World/ of X with emojis in’t!’ . Sometimes the world of vituperation in Elon Musk’s X of antagonistic aliases and emojis used ironically or sarcastically to emphasise contempt of others really makes me think about the emotional world offered to model acceptable behaviour. X was once called Twitter, and represented by a silly but kindly hopping bird, and was liberatory of more than the nasty. An opinion piece.

Let’s look at how communication is understood at its best in its greatest art. Shakespeare was a poet and a dramatist. Here is an example from The Tempest, sometimes thought to be his last play:

MIRANDA, ⌜rising and coming forward⌝ O wonder!

How many goodly creatures are there here!

How beauteous mankind is! O, brave new world

That has such people in ’t!

PROSPERO ’Tis new to thee.[1]

He loved to show in his late plays that he could write verse that expressed wonder at that visible beauty and joy of a diverse world. That was the great poet playing at what makes life into beauty. He then undermines that beauty in the eyes of its young perceived, Mirands, and wonder by allowing another character, he father Prospero, to query the virtue of what has been described, and infer that such a response is just the naivetè expected of a young innocent.

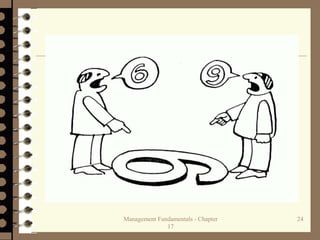

Prospero hears the wonder in his daughter, Miranda’s, voice at seeing a group of people from a world unknown to her. But he quietly ensures that she knows that such people would not seem so wonderful if she had known that group of people longer and been their victim, as he has. That’s the dramatist at work, showing that there is no perspective on anything that one person sees in the external world, which can’t be countered by people with a different approach to the same sight.

Prospero was truly a victim of political machinations in his past on the Itslian mainland and was isolated by it – even to the symbol of being king now only of an unpeopled island. However, his response to his disappointment in the social world he once knew is not a healthy one. It is a response that replaces control over other for treating them with love and trust in their autonomy. As a magician, he can control the supernatural world, and thus, he binds the spirit, Ariel, rather than building mutual relationships with that spirit’s powers. As a ruler of no human people, he controls his one non-human servant, Caliban, with punishments and bondage to him. As the patriarch of a one-parent family, his relationship to his daughter is as controlling as his relationship to Ariel and Caliban.

What happens in the bit I quote, though, shows Prospero in a kindlier light: having learned that what he once called love or attachment was sometimes the much crueller bondage I described above. In the course of Act V of The Tempest, he will renounce his control of his daughter and allow her to form bonds to other people than himself of her own making and regulation, freeing her own volition and at the same time exposing her to the necessary risk of a more autonomous life. Nevertheless, he still reminds her that there are other perspectives than her own current one.

Encounters in drama are like that. We can not not be in conflict when it matters to us how an argument is resolved or a course of action fully planned. But many of us, and, yes!, I see I have done it myself, in frustrated response to views I though evil in intent snd effect, attempt rather to control its expression through ridicule or empowered and entitled statement, rather than win others over through interaction. But in Twitter, as it once was, the balance of communication started as a debate. It is now an exposure of rigid viewpoints against each other. The present algorithms to which we do not have access ensure this is justified by Elon Musk’s statement that free speech is forcing people to hear things ‘they don’t like from people they don’t like’.

It is a recipe for conflict that does not even aim to improve the perception of an issue from differing viewpoints but only to allow people to show undisciplined hate for each other. I have a principled stand on the current debate on sex/ gender but I still think I can show how opponents of my position use such exposures.

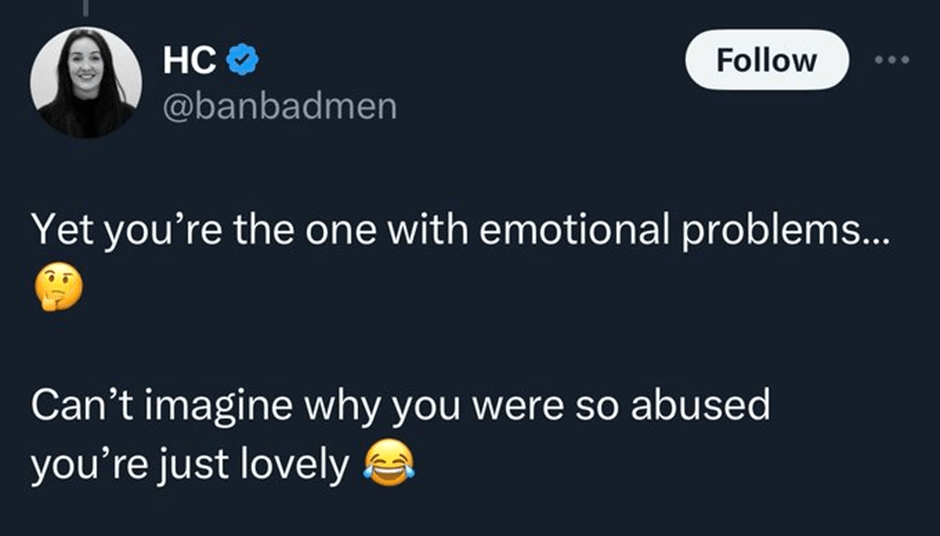

The example I take is from someone I don’t think I would like, but the person hides under a pseudonym, uses a photo-identifier miles from the word-picture given in text of an retired person of high self-asserted status and a symbol of success and excellence – words that run through the masthead srlf-punlicity of the account.

I came across their post simply because they chose to respond to protests from people. I knew that they were being singled out for a pile-on of antagonism by her publishing their photographs. All of the accounts wore their own identity, unlike this one, called @banbadmen. One had shared the experience of child sexual abuse against them. Hurt, they asked the oerdon to desist characterising their response as hurt from someone who was not in touch with the feelings of others.

Here is the response that brought all the above to my attention:

Now, this is an example of the ‘brave new world’ of supposedly open communication. The owner of it displays that they have purchased the right for longer posts than the minimum to which others are restricted but does not use it here. Instead, pert remarks attempt irony that, in the usual way of things, becomes highly sarcastic, doubling down on the hurt caused by labelling the abuse tbey shared that other’s ’emotional problems’, whatever those problemz might be meant to be. Emotion is not per se a problem.

Then, the thoughtful emoji, meant to indicate a query or problem to think about, but which is motivated here entirely by a kind of entitled arrogance and assumption of superiority, a condescension to someone typed as not capabke of thought or reflection. Top that with a further sarcasm that blames the victim of past sexual abuse on themselves, because they are now a man though once they were a child, completed with a LOL 😆 emoji except they use the one with tears to emphasiss the bathos. The implication. You aren’t very nice and that’s why you were abused.

That is Elon Musk’s X now. A place of thoughtless rancour propped up by communication shortcuts that excess on the pain tje communication was meant to convey alone by words. Needless to say Ibreporyed the ad personae attacks on people by the original tweet withnits photographs and blocked the vile participant. They must have noticed because they blocked me. None of that is st all troubling. Some people communicate only to hurt.

Now, I know no way the person will send this or I might have tried to win them over to a kinder view of the world that oies not hate trans women because they remind them given their binary blinkers, they hate all men. But right now, I just wanna be grumpy. Sorry!

All my love

Steven xxxxxx

[1] William Shakespeare The Tempest Act V, Scene 1, lines 215ff.