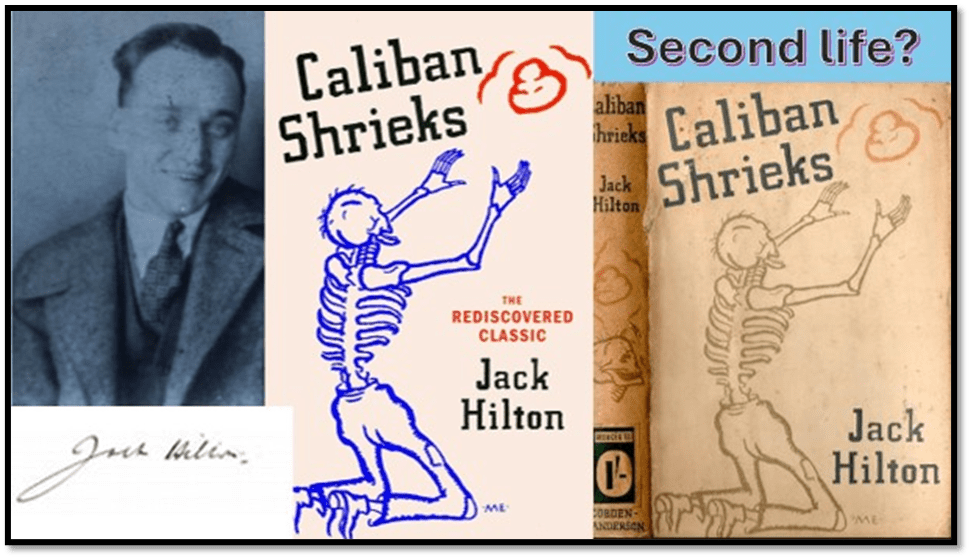

‘CALIBAN IS A MAN YOU SHOULD KNOW WELL. … He holds opinions about his rights; such foolishness he should overcome’.[1] This is a blog on Jack Hilton (with introductions by Andrew McMillan & Jack Chadwick) [2024, but first published in 1935) Caliban Shrieks, Vintage Classics.

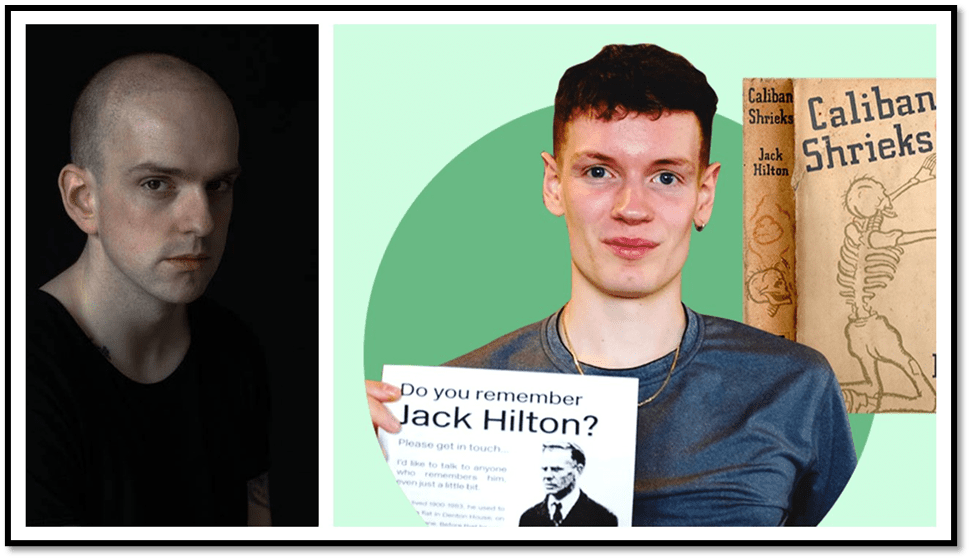

Did Jack Hilton leave a legacy? If so, how should we feel about its need to be rediscovered. Implicitly, this blog is about never thinking of legacy unless you are in control of it. And you are not. Jack Hilton was admired by George Orwell. Jack Chadwick tells us, in a radio interview for Front Row on the BBC, that Orwell actually wanted to do investigation into the working lives of working class people by living with Hilton in Rochdale, in order to do his research.[2] Hilton declined but advised that Orwell went to Wigan to live with miners there. The writer did so, and The Road to Wigan Pier in 1937 was the result. What Jack Chadwick, who rediscovered the novel in the Manchester Working Men’ Library also found out was that Orwell especially admired Hilton for not writing in the fashion of ‘proletarian realism’ that was the fashion of the day but with an attempt to capture the same kind of descriptive and sometimes ironic consciousness that the modernist novel had. There is then in him something of an insistence on the same sense of a voice that does not describe the world in terms of realities but also of an aware consciousness of the difficulty of ever doing such without casting over the thing you describe the language of jargon and mystification.

This is Hilton’s complaint about almost every left political party and trades union, though he was involved with them all. I think Jack Hilton’s own Preface, whose opening I quote in my title, contains its own answer, we all should know Caliban well because we all equally hold his opinions, but we also share his unending abjection before Prospero, a failure to achieve rights we want to achieve. In that, we are as spineless as the bookish left. He dispatches the Communists via his scorn at the emptiness of their language other than as it is used for identifying their cult and its dogma to each other.

Likewise, the Independent Labour Party (ILP) perform activist work of all kinds, ‘providing it does not entail physical clash with the forces of law and order’. Proud of their ‘very nice’ clubs and branch houses over the country paid for by the subscriptions of a middle-class membership, they do it because they like to sees their name (ILP) everywhere, ILP actually means, Hilton says: ‘Inflated Little Pawns’.[3] Above all this is a Labour Party he says who use the working class to get power for their conscience-full sense of their entitlement to it. They speak a lot of words but:

with a bit of sob poetry and visions of a beautiful, idealistic, utopian future, they send the dull-witted unfortunate victims of capitalism’s lunacy home – hopefully to wait until the High priests decide which shall be the particular day when they will inaugurate their “Socialism in our time”.[4]

No party comes out of these diatribes very well and even the working-class victims of the ‘lunacy’ of capitalism are described as ‘dull-witted’ for believing in the voice of Labour speech makers. Auden was less enamoured of this trait, recommending it mainly to those who would like to find “a bitterness and hatred of life” to ease their critical-of-all-things-human souls. And he is, I think, correct in a way, for the voice of the book is surely the character he builds from quotations from The Tempest and an imagination of how such a creature would speak and feel under the lunacy of a capitalism that has enslaved the working class in the interests of its ruling class.

As Hilton says:

I know the musings and tirades of my modern Caliban flout all the accepted rules of writing, but, “You taught me a language, and my profit on’t is, I know how to curse. The red plague rid you for learning me your language”. [5]

We are not to expect a political programme from Caliban but the unleashed voice of his bitterness at the class who still own the language they taught to him, even those in the Socialists parties whose difference of language is merely one of degree not substance – equally without concern of the enslavement of Caliban having to desire the bread loaves kept from him to feed those who already have plenty. The ‘red plague’ however is ambiguous in Hilton’s book in ways unintended by Caliban – I think Hilton does hold out that violent revolution is a possible fate for his Prospero class ⁸rentiers and food hoarders. And we do not expect such a voice to speak of the rights of the many – recognising that these would be just words, as his list of Socialists fail to realise, but of ‘his rights’. Hilton uses the italics here for a purpose – Caliban knows only what is done to him, its effects on him alone and calls only for his rights, not for countless he claims to represent, that, we can infer, is the role of the middle-class socialist.

An if there is biography in this, it is that of a man who knows he was born a ‘softy’ and who realises that he is being used as a ‘pawn’ (a silent one so thus not yet an ILP member – Inflated Little Pawn – in a game that pleases only those who use speech to command and control others. That insight that the working class man is made to continue ‘vulnerable’, whilst not being allowed to know it, comes through war experience. In the following speech helplessness and impotence are the only realities. Still (perpetually silent) and passive in a war fought by machines serving their own purposes – not even, at this point, cursing:

What are we puny things, …just a few of the million pawns, similarly placed in a stupid stunt. Dug in, relatively passive, incapable of functioning, being just there, firing feeble shots into space, ,,, We are just there to suffer neurotic shocks, inhuman physical hardships, become lousy but stay there until relieved – maybe never return.[6]

This is not then an autobiography of Jack Hilton, but an image of the Caliban he can be; but only when given a language that is not his own that can speak of how he owns nothing while some, a very few, own everything- including the loaf he skeletally years towards in the cover illustration to the book.

Of course, there is an approach to the events of the life which are summarised in the authors Wikipedia entry. It summarises the life thus:

Born into a large working-class family, Hilton grew up in a slum before starting work in a cotton mill at the age of eleven. He fought in the First World War before a period of several years as a vagabond. Upon settling in Rochdale in the latter half of the 1920s, he took up odd jobs in the building trade. During the Great Depression he began to organise for the National Unemployed Workers’ Movement. After a protest in 1932 for which he was imprisoned in Strangeways, Hilton was barred by a magistrate from involvement in the organisation of future protests or political actions with the NUWM. He turned to writing instead, and soon afterwards a tutor of his at the Workers Educational Association stumbled upon a notebook containing drafts by Hilton. The tutor posted the texts to the modernist literary editor John Middleton Murry who invited Hilton to contribute to his magazine, The Adelphi. Hilton’s contributions evolved into his debut novel Caliban Shrieks, published in 1935.

The real Hilton was a union man but even these get slated in Caliban Shrieks as ‘in the groove of conciliation, adjustments and inertia’. They soak more money in dues from the workers to be ‘spent on beer’. Yet he is one of them: ‘They call themselves brothers (I should say we, for I’m one of them)’.[7] ‘I’m one of them is a moving moment, for Hilton here acknowledges that he is not the Caliban who speaks only but another force for the inertia that entraps Caliban. This is the reason, I think for the bitterness – the bitterness of impotence, so beautifully conveyed in the soldier’s infertile stance, ‘being just there, firing feeble shots into space’.

We can see that he was patronised by the Middleton Murrays of this world but their aim was, he concludes, to just him more impotent language. Yet amongst these, with his lost and unread books – all speaking a language not of the working class and replete with references to Shakespeare – Hamlet in particular – that he cites.

A collection of Hilton books; photograph by SongOfMyShelf – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=71508433

He has severe condemnation of them – condemnation that might even reflect on his Hilton self, the one who wasn’t the man who returned to earn his loaf as a Manchester plasterer. It is a troubling moment for the condemnation is almost entirely homophobic. And not, he says of it that ‘with such vituperations I used to lash myself and soliloquise and feel much eased’.

I was unabashed, undaunted and condemned everyone. Readers, dreamers parasites or work-animals, damn you. Hermaphroditic, double-sexed, god and mammon Non-Conformists, or Coriolanus bloods of blur, … Understrapper servility, holy-Michael piety, meekness, watch your step, every step a life sentence to orthodoxy. Stupid pawns, robots, unimportant pygmies, bowing, scaping, never getting within a thousand miles of the oligarchy you serve.[8]

Every sentence you write that is not Caliban is a step to ‘orthodoxy’ in a trades union or elsewhere. This is the bitterness Auden rightly discerns, and it is directed at Jack Hilton too. As Andrew McMillan brilliantly observes:

There’s a[i] sense of Hilton having a certain idea in his mind of whom a generalised reader of a literary novel might be; he speaks to them (to us)) sometimes in anger, sometimes with disdain, sometimes as though we’re part of the elite who is causing the conditions that are being sown. … His imagined reader is Prospero not Caliban.[9]

McMillan might have meant this but I think the issue unsaid is that, in as far as we step to conformity – do their work and learn their language – even Caliban apes Prospero and it is appropriate to excoriate that other self. Is it this the reason, other than pointing out that they are both Jack makes the rediscoverer of this book, Jack Chadwick, a working class intellectual who speaks above himself speaks of ‘two Caliban’, for much gets doubled in this book, although there is no evidence of the self-hating in the younger man:

I need to ask why Hilton’s lashes and vituperations, which he says are directed to himself are so bound up with hating binary crossers and transgressors – the ‘hermaphroditic’ for instance, the impotent, those locked into being pawns being as bad as those who are locked up because they accept their stuckness. For me, this makes this book BOTH difficult to read but also important to do, for it is a book of the unresolved, in a way that The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists is not. I think there is still work to do about voice in a novel of this kind – the novel of committed self-hate at the writer proving his double becoming as speaker of the socially revolutionary and barrier to that revolution. Meanwhile I bless John Chadwick for his detective work and fellow feeling – for he knows this is a book of psychological complexity as he told BBC Front Row audiences – and Andrew McMillan for taking the message from it that he must ‘persist’. And John Self may be right about the simpler pleasures in the book:

But the style at its best also contains an energy that drives the reader on through the book’s loose structure – “Try it, you stiff-collared puritans. Get some idea of what men are, outside your little mousetrap circle” – or provides glints of comedy. On employers demanding ever faster work from staff, Hilton wonders “which firm will introduce rollerskates first, Henry Ford’s, I suppose”. There are surprises, too: we forget how widespread support for eugenics was in the early 20th century, until Hilton recalls his own enthusiasm, and his determination to have a vasectomy to further the cause. (Happily, he was turned down for having a “dirty mind”.)[10]

Meanwhile I will go on worrying about why the working class are nominated ‘Beastly Blondes’, for it is most dissonant and seems so mixed a reaction to the horny-handed sons of toil stereotype: ‘Beastly blondes of toil, willing, eager , eaters up of production’. I cannot even scan the emotion therein. He sort of loves and hates ‘the men, well, just BEASTLY BLONDES’.[11] A little later, he summarises what the disabilities of marriage and courtship and monogamy after marriage mean to the ‘rough spun HE MAN’. His view of sex, especially male sexuality, comes under the same category of hated and despised things as other human behaviour. Yet he admires the working women for admiring the animal working men and imagines it:

You feed the brute of a husband, you continue your life of mill industry; you drudge and table the beefsteak, you recognise his mastership, amid it you are proud of him, and devote much of your muchness to keeping him with you till the end of your tether.[12]

No woman is praised for this or roused to rebellion – and is indeed scorned for not doing the latter, preferring giving beefsteak to beefsteak – it sounds much like the understrapping behaviour he blames in working class foremen. The thing is Caliban hates everything even the use of reasons like ‘call of the wild’ to justify male lust. Yes. There is much to still learn of Hilton from his inability to show, but yet demonstrate the confusion between, transitions from ‘softy’ to the ‘masterful, from brilliant analysis of an evil situation to impotence in the face of solving it and other people’s failing solutions.

Do read it.

Much love

Steven xxxxx

[1] Jack Hilton (Intros by Andrew McMillan & Jack Chadwick 2024 -xxxi, first published 1935) Caliban Shrieks Vintage Classics.

[2] https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m001brqb 27 mins in. (Front Row interview – Released On: 07 Sep 2022)

[3] Hilton op.cit: : 133f.

[4] Ibid: 135

[5] Ibid: xxi

[6] Ibid: 25

[7] Ibid: 143f.

[8] Ibid: 36

[9] Ibid: xf.

[10] John Self (2024) ‘Caliban Shrieks by Jack Hilton review – lost voice of the north’ in The Guardian online {Tue 27 Feb 2024 09.00 GMT} Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/feb/27/caliban-shrieks-by-jack-hilton-review-lost-voice-of-the-north

[11] Hilton op.cit: 61, 63

[12] Ibid: 74