Nicholas Thomas’s critical-and-autobiographical reading of Gauguin’s time in Polynesia, and the determinations in the man that led up to it, explores the contradictions in the intersubjective and intrasubjective confrontation of cultures. This is a blog on Nicholas Thomas (2024) Gauguin and Polynesia London, Head Of Zeus Ltd, in preparation of seeing him at Hexham Book Festival, Queens Hall on Sunday 5th May 2024, 11 a.m.

What follows is a preparatory blog before seeing the event mentioned above. I am so intrigued by how this event will be handled and am hoping it will include art works commented upon by Nicholas Thomas and discussed in audience questions. But there will inevitably be other issues. Although this book has been warmly welcomed by art historians, it is a refreshing change from the workaday products of that discipline from a scholar at ease with teaching and learning in archaeology and anthropology and in museum as well as art curation – and perhaps there are strong reasons for bringing those areas together in some way. So I expect to update this blog after the event, even if very briefly. However, for now, I prepare myself by addressing what I find most illuminating in the learning prompted by the book itself.

However, I will try first to clear up some definitions of the words in the title that are central to my approach to understanding the brilliance of Nicholas Thomas’s reassessment of Gauguin and his contact with peoples that led him to grow as an artist and person. Thomas’ book pits itself against simplistic approaches that suggest that Gauguin merely imposed himself on Polynesia, translating it only into his own terms and thus reducing its power to comment on other societies as an equal and due that respect. Thomas makes it clear that Gauguin grew in parallel with his understanding of Polynesian culture – even where this understanding was very partial. That didn’t stop Gauguin from acting sometimes like the very worst of the colonial settlers, as Thomas shows for instances in the sad episodes where he voiced the European settler view that many locals needed more policing to cause them to desist from stealing from settlers, and called on the colonial military, when indigenous Polynesians resisted French intervention, ‘to fire the cannon, burn, and kill’ them. On top of this, he could boast of having his bed invaded with ‘des gamines endiablées’ every night making up for the fact that his syphilitic sores sometimes put more serious sexual partners off.[1]

But Gauguin, as Thomas paints him is also a man learning from Polynesian culture and from individuals in it. In my title, and I would suggest in life generally, contradictions occur within people. It is as if two or more agencies were in conflict inside the person and between persons. However, the differentiation of these conflict domains is not clear cut. Conflicts or agreements that occur within a person can be projected into the debate between two or more people, and what happens in the latter can also be introjected into a person’s inner conflict and complicate it. Sometimes, but more rarely such introjections and projections can resolve conflicts. I use the terms intersubjective and intrasubjectivemuch as psychoanalysis does, specialising as that discipline must, on the shared domains in which selves and others come head to head, heart to heart, body to body within one’s interior experience and the shared experience of groups, including dyads (groups of two).

Without this basic process occurring, transference (and counter-transference) could not happen. I believe they do happen whether they are named as such or not and that good research will stand back from over-confidence about the meanings attributed to persons and groups for that reason. Thomas is very special. He has found a way of showing that any discipline that finds itself over-interpreting things to illustrate a belief, even a necessary one like acknowledging the existence of misogyny, colonialism, racism, sexism or heterosexism, possibly should stop short from interpreting human action with a broad label. Thomas picks up a number of such over-interpretations regarding Gaugin that have led him to be labelled simply as a ‘syphilitic paedophile’ or a colonialist imposing on the colonised Western values and practices; especially Western male values and practices on colonial women. Amongst these are people thought expert in commentary on Gauguin such as Griselda Pollock and David Sweetman.

In riposte to them, Thomas does not preach in favour of Gaugui. He merely shows the conflicts in Gauguin’s self-representations in the eyes of others, and his own actions, thoughts and feelings as they arise and get recorded, often below the conscious or intended meaning of the records (letter, manuscript notes or published writing and so on). This occurs both in Gauguin’s manifest musing and in how Thomas demonstrates how interactions with Polynesians impacted on that musing. This you would expect of an anthropologist rather than an art historian – for the latter are eclectic only by fashion or in search of a publishable thesis. The latter often raid the letters for ammunition against Gauguin. Thomas urges us to take a deeper dive into them and their perplexed views of life and art in combination. Take a central one in the book relating to the painting, Vahine no te tiare, he made in Mataeia of a voisine, a neighbour, which he thought would ‘initiate’ him ‘into the character of a Tahitian face, ..’.

‘Vahine no te tiare’ and drawings of female drapery in Mataeia. Thomas takes to task Western feminist art historians who see this clothing as a Western imposition and not bound into the ritual life-forms, though not necessarily rituals of religion.

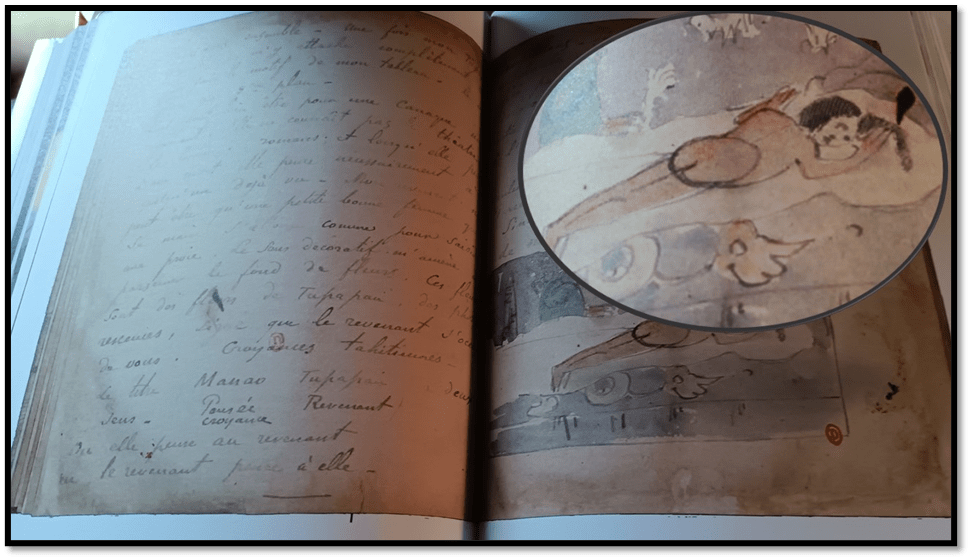

I take the word ‘initiate’, relating to entry into, in the case of the Eleusinan Mysteries ‘down into’ a religious or psychosocial mystery, seriously. Thomas likewise wants to see Gauguin explicating his art as nuanced between the need to BOTH “facilitate the understanding of his painting”, in his words to his wife Mette (a translator), AND feed his belief that certain understandings are in themselves mysteries in the fullest sense of the word: ‘soyez mystérieuz, be mysterious, was the seductive inscription on one of his earlier reliefs in wood’.[2] Gauguin is fascinated about that which goes on within the domains where a truth is looked to be made manifest physically. By saying ‘physically’, I mean, for example, ‘visually’ primarily but not only that. It works too through the inscription work, art seen within art in both painting and sculpture. These features too suggest inner depths or layered meaning that work both cooperatively and antagonistically with each other in the art work.

He combined iconographies, for instance, in a way Thomas calls syncretic. He uses the word to reflect on syncretism within Gauguin’s artwork, but also applies it to the interaction the works have with a series of ritualised practices in diverse cultures Gauguin visited (for it is found in Brittany too) and in interactions between them cultures in colonial or national contexts, religious and domestic. Thomas facilitates us to read Gauguin afresh in his manuscript notes for Noa Noa.

While she determined with great interest some religious paintings by Italian primitives, I tried to sketch some of her features especially that smile, so enigmatic. She made a grimace. Went away, then came back. Was it an inner struggle, or caprice (a very Maori trait) or even coquettish impulse, to surrender, only after resisting. I realised that in my painter’s scrutiny there was a sort of tacit demand for surrender, surrender for ever without any chance to withdraw, a perspicacious probing of what was within. … That melancholy of the bitterness that mingles with pleasure, of passivity dwelling within domination. An entire fear of the unknown.

I worked fast, with passion. It was a portrait of what my eyes, veiled by my heart, had perceived. I Think it resembled the interior. That robust fire of bounded strength.[3]

Thomas shows us that commentary too often leaps on the sexual suggestivity played upon throughout this passage. But he also shows us that we do not have to discount such readings in seeking deeper ones. When Gauguin tries to understand the behaviour involved in this exchange of views of each other between model and artist; and of each other’s valued objects ad behaviours he inevitably goes ‘within’. He penetrates that which lies in the unspoken gaps. These gaps include those between the poles of a binary range: passivity and domination, bitterness and pleasure, and resistance and surrender. The passage is obscure only if it is read on its surface as a series of statements rather than, as prose of this kind mostly is, an exploration of interactions around a multitude of possible stances in one’s thought, feelings and action. It is too easy to leap on the undeniable misogyny of the expectation of a ‘coquettish impulse’ or the racial stereotype in labelling ‘Maori’ traits as an expectation that only could pre-exist when speaking of a woman and the colonised in patriarchal colonial society for it is only Gauguin checking whether a shallower interiority might explain the behaviour he reports, in both of them, than a deeper ‘inner struggle’. Thomas never claims Gauguin is beyond the narrow thinking of his times, just that there is complexity and varying depth in his thinking and feeling, especially when enacting it in paint or ceramics or even discoursing about those actions.

What strikes one about this prose is the insight into the effect of his own gaze on his model as, in itself, a process involving multiple potential means of acting upon what the model offers to him, willingly or otherwise: some imprisoning, others freeing, pleasing or bitter, masochistic or sadistic, and locked into a need to know and a contradictory fear in the desire to know what lies beneath all ritual. Gauguin only sees when the heart ‘veils’ his eyes (the mysteries of initiation live in that sentence). He seeks to see within or what ‘resembled the interior’ and comes up with something contradictorily defying all bounds but still contained, a ‘robust fire of bounded strength’. He sometimes painted that mix of containment and outward flourish. I see it in these two paintings:

Something burns centrally in each of these frames and threatens the bounding of the interior or the sustaining tree which divides and orders the night scene. Thomas knows the culture that these paintings (almost realistically) recreate, can embody ritual semi-divine forms in the names of recreation art and initiation ritual. Thomas revels in the fact that the choral singing in the 1892 painting is both ritualised and every day, as ritual oft is, by saying ;some people are marginal to the main group, less engaged than others, or taking a break: …’). The dancing in the 1891 painting is transgressive – to nineteenth-century Western eyes at least (in the miming of traditional male movement in the woman at the back of the dancing couple whilst the other mimes a traditional female role). These dances were banned by the Catholic Church in Tahiti. Yet for Thomas we cannot say this dancing and or choral singing is either ritualistic or realistic – it is both. That is what it means to Describe Gauguin’s approach as syncretic. He makes the ritualised speak through the ‘real’ – even in the actions of participants who seem to discount their participation in it as just ‘everyday’ to them. That is how Polynesians acted and still do, Thomas says below. This the fact even without considering the ‘syncretic’, in its more usual meaning, in Polynesian-Catholic iconography of the period. I will consider the latter in later examples given.

If the great fire and the three figures in the background vaguely suggest some ritualistic activity, this was actually just a painting of an outdoor party. [4]

I would add the phallic life-trees to the elements mentioned above. However, I think there is a slip in the nuance of Thomas’s prose in this sentence with regard to the syncretic, which also bridges the everyday and the ritual to my mind. I think what is ‘actually just’ a real event and that may ‘vaguely suggest’ something beyond that event are, in Gauguin, the same thing, as the Vision du Sermon painted in Brittany, with, as Thomas points out, the same transverse tree, perhaps phallic therein too.

Thomas’s book could have been of course many books because of the richness of its approach and reference: it sets so many hares running. I like that kind of fertile thinking. For instance, he has, it is clear, much to say that is pertinent to Polynesian cultural traditions and Gauguin about the interest of both in transexual iconography and representations that unite interest in cultural research and interpretive gestures which invoke the dissolution of sex/gender boundaries and binaries, as in the dancing in Te fare hymenee above. I will return to this theme later.

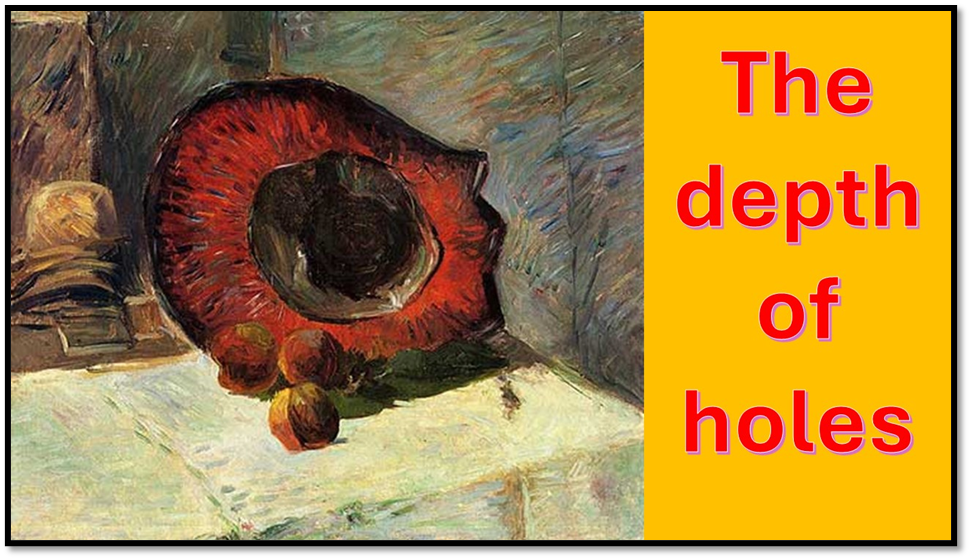

However, just as we do not (in truth cannot do for it is too intrusive into what this book sets out to do) get elaborated on this or other themes of interest, so often I have wondered, as I write, if I have read into Thomas what he refuses to directly say. I want to explore this around the nature of Gauguin’s interest in the art of the occluded, that which is occluded because it is veiled, hidden or deep, approached through a hole or gap. In my view this finding of holes and gaps in the representation of life is akin to the desire to ‘be mysterious’, though finding that mystery in the everyday. This seems to be the issue with the experimental ceramic art throughout his career and in the tendency in his art to create a perspective that is intensely claustrophobic in its effect – the feel of being shut in and contained or in fear of falling into that. See it in the ceramics which I still feel too nervous to discuss but which I love in the following collaged examples used in the book:

The sense of pained interiority, where every external seems pointing inwards to some dark hole of the subjective within appals and excites me in looking at these objects. This is so in the one experimental picture, of a type that Thomas believed Gauguin never recreated, that is a still life of a red hat, where the viewer’s vision is led down a black hole in the hat’s centre – in fact there is a swirl of dark colour in the hat’s supposed bottom. He painted this as he began work in ceramics, Thomas says, to hide faces with it, as his art sometimes did. Thomas says it is an odd composition where the hat has ‘an irregular brim, round apart from several parts at the back, which are positioned to suggest a head in profile’. He thinks it ‘whimsical’ in this case, but I think he does so by ignoring the visualise interiority in the painting’s ‘head profile’. The latter I see as shown in our absorption as viewer’s in picture’s fascination in the black hole or gap at its own centre.[5]

I sense these dark voids in different genres painted by Gauguin but they also elide with that upsetting verticality of perspective as you look at things that seem to recede, not to distance alone but to imagined depths, like the cow in the Breton sermon piece. I will look at versions of this later but they are in Gauguin’s early landscape experiments too, like those I collage together below:

Père Jean’s Path (1885) – om your left in the collage – is, Thomas says, trying to invite you in, whilst holding you back from clear vision by a curtain of trees and foliage that somewhat disturb the effect of the red roof seen in gaps between them and reflected in a small waterway between the tree on its banks.[6] The eye moves reluctantly on, often being led down to shadowed enclosure.

The Bathers (top right in the collage) bathe openly in the hot sun – at least the young naked boys – the girls remain sun-hatted and fully clothed – on the edge of water below them and in a landscape enclosing them but also full of holes – deep caves perhaps. The landscape bottom left (Chou Quarry 1882), from a series of quarry paintings, such as Cezanne popularised, feels the most claustrophobic in effect because everything descends, with the help of the spectator’s eye into a declivity falling to the left. At the heart of the rock is the shadowy entrance of a cave – another depth to which the picture slides us. Looking at the picture creates vertigo as well as claustrophobia from which the dark fringes of the sky offer no relief, rather a lid to keep the eye within the painting,

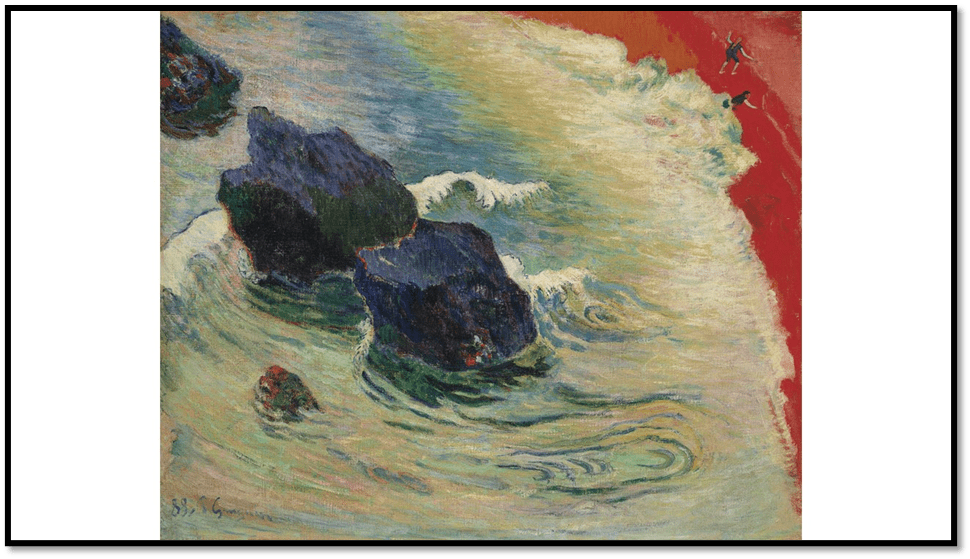

Vertigo can be recreated in the imagination of a spiralling fall into a void and this can be implicit in Gauguin’s painting methodologies. Gauguin did not exclusively paint as if from a point of view above objects or the landscape but he did it often. Thomas attributes this to the ‘high viewpoint’ typical of Japanese painting and suggests it is forms part of his experimentally innovative way of working.[7] The most startling example being in Wave below, though I sense it too in the 1888 Fishermen and Bathers, where because of the reflective river base, one never feels to have reached the bottom of what the eye seeks to find below surfaces.

In Wave (1888) a vantage point yielding this vision is hard to imagine, especially give the miniscule stature, from that perspective, of the people on the red beach – one of whom seems to be being sucked back into the sea. Vertiginous, unstable, the sea opens up voids of dark coloured sea beneath it, deeper than we can rationalise given the apparent proximity of the beach. The rocks themselves are part holes and create shadows around them more strange in depth than they. According to Thomas this piece is extravagantly Japanese in style but this is certainly not the vision of Hokusai or Hiroshige.

It may be that these experimental plays with styles that Gauguin persisted in calling ‘primitive’. Primitive is a word which seems to mean in his use merely painting whose main aim is not a clear representation of perceived reality unveiled by meaning or overt design. This is why the ‘primitive’ is an effect that continues in some Polynesian examples of his painting, although Thomas brilliantly shows that there was no sense in which Gauguin could have thought of Polynesian peoples as ‘primitive; in a limiting way, or from a patronising attitude, except for some necessary grounding in the conceptual anthropological frameworks of the period.

The landscapes in the collage above do lift the vision of the viewer up into the skies, especially the one, Paysage tahitien (1891) representing a midday scene (bottom right) but even in thel atter, a pattern of diagonals criss-cross the eye down to the path that leads into the obscure heart of the painting; one, a thick grey- black gap across the highly coloured otherness of the painting representing a declivity and shadow. The dusk scenes bear down in onto you: the pigs in picture Haere mai (1891) guide the eye down into a declivity at the bottom of the frame. In the dusk paintings we are aware more of the effects made by Gauguin’s cloisonnisme methodology that emphasises the sharply edged patches of insistent monochrome – the purples for instance. Thomas defines the cloisonnisme by identifying it too as the practice of Bernard from Gauguin’s period at Pont Aven, saying it ‘confronted the viewer with solid masses of intense colour, rather than the vivid mixing typical of Impressionism’. He thinks it based on the influence of medieval stained glass .[8]

For my part, and as with the adoption of ‘Japonisme’ high viewpoints, this is less to do with cultural influence than finding a style that stressed containment and edges. The beautiful painting of Martinique, preceding the Polynesian pieces, Tropical Vegetation (1887), on the left of my collage However, he also uses the evoked gloom under the trees, contrasting with the star like effect of the white flowers on right to create a kind of hole in our vision to its left, framed by the strange formation of the tree, with its own lean to the left and doubled with patches of shadowy wet ground across the reddened earth. These paintings for me define the kind of intrasubjective containment of energy in Gauguin’s painting.

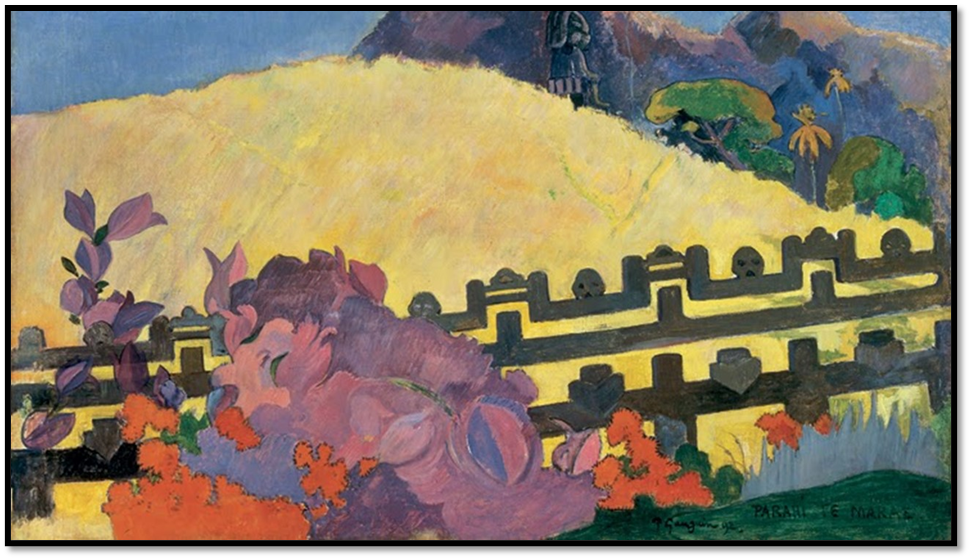

In Polynesia we see other startling effects of containment that arise from much more complex and conflicted energies in landscapes interacting with architectural framing. They are powerful in his woodcuts but I have no confidence in seeing these in a way I can use currently. The painting (below) Parahi te marae (1892) is a deeply syncretic painting of an enclosure. As Thomas says: ‘Marae were and are ritual precincts, which typically consisted of a substantial rectangular space marked out by a stone wall’. He also says that, in this picture Gauguin is most guilty of cultural appropriation, using Polynesian symbolism and imagery for his own Western-trained purposes, Thomas says it is unlikely he looked closely at such sites and that imagery on the fence enclosing the most sacred space is grossly oversimplified into memento mori rather than by the rich imagery of the religious myths that would have been found there (the daughters of a king ‘pissing from their swing into a bowl’ being drunken by the hero Akaui). Skulls are much simpler than this.

Thomas shows too that such anti-imperialist point-scoring is if limited value since though Gauguin invented forms where he did not understand the original, he also ‘actually did represent environments, scenes, people and practices on the island naturalistically’ if not necessarily on site in ‘plein air’. And this painting is respectful in its invention, hardly looking back to officially dead cultures, displaced by the Western coloniser and paradoxically then hypocritically mourned by them. Look at the piece above again.

Parahi te marae is a painting that genuinely causes a viewer’s aspiration to rise, catching sky and imagining unseen mountain tops, hidden in front of which is an idol, with some obscured detail. The aim is to show the holy aspiration of a viewer not what that aspiration meant, for he could not know that, in respect to the population. The aspiration lies in the mound of golden light and the beautiful purple-red leaved plant that strays over the fence towards it. We are brought back to enclosure of course by the same cloissonisme methodologies (apart from in the beauteous fringes of the yellow hill) by the black-grey fence with skull motifs, but only in an act of contradiction and tension – the fear of the unknow contesting aspiration towards its transcendence, as its believers felt must lie there, despite the banning of these sites by the Catholic Church. It is a most remarkable painting.

I promised earlier to look again at syncretism and the painting above creates a bridge from my concentration on landscapes of taut contest of open and closed elements therein. Syncretism s most easily perceived in the blending of supposedly opposed religious traditions but before I look at this in more detail, I want to stress how it is also a mode of bridging the mythic and symbolic interests in Gauguin’s iconic work and his rendering of them in everyday context, in which a naturalistic take on genuine Tahitian culture IN HIS OWN PERIOD shows where it was mixed with Western traditions but not only as imposed forms.

Thomas argues that Gauguin did not see the clothing chosen by women in Polynesia as an aesthetic imposed on them even though it did not suit them (after all, they thought it did). Rather he shows how these women transformed the signs in those clothes to ones they understood and that they like and valued: it is, as if, they appropriated them, one might say. This is not that Thomas is ignoring the ills of colonial appropriation of other cultures but showing that indigenous populations could transform their experience of this ‘appropriation’ by colonials in ways that did not represent them, to themselves or others, from being seen merely victims or subordinates (see his sketches of that clothing reproduced in a collage above to see that Gauguin appreciated that fact).

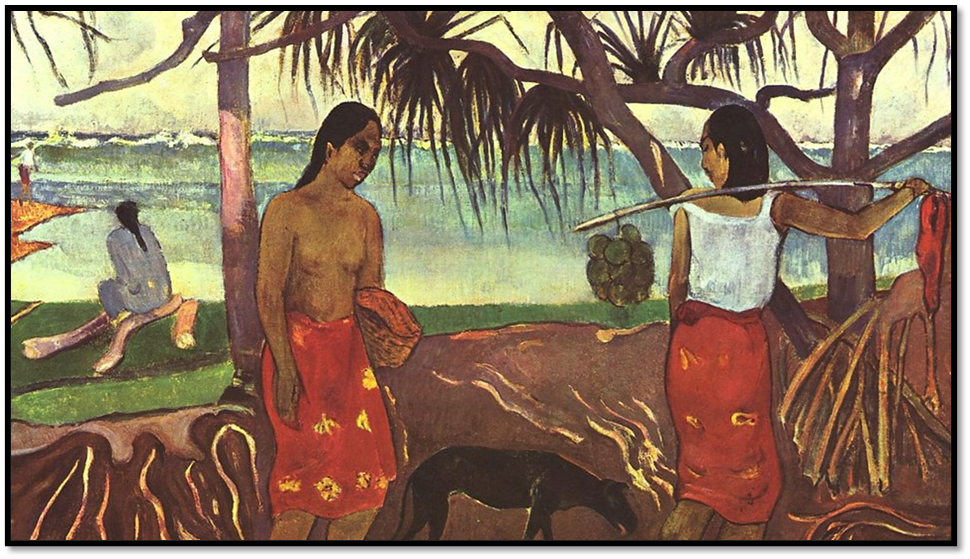

The piece I Raro te Ovriri (1891) is important to Thomas’s argument. He once thought, he tells us, that its upper half was a naturalistic landscape whilst its lower half was symbolic: ‘looking like ‘a mass of arteries, a pulsating, sinuous, convoluted surface, traversed by two women, who were perhaps taking offerings to some shrine’. To his surprise Thomas visited the area again to find that a ‘number of common trees, and pandanus in particular, have roots that often fan out over the surface of the ground, especially … near a lagoon’s edge’.[9] This is typical of Thomas. His point is that symbolism and naturalism are not at war. A painting can mean things without insisting on those meanings alone, as can what an intent perception actually sees, which is often veiled by the projected interior of ourselves.

This painting does lots of things but one is to show that Polynesians do not just follow stereotype. Hence it is legitimate to ask what the miniscule trousered figure in the distant surf, is doing in the water. Likewise we ask how, if the women have sacred intent in carrying their offerings of food, it harmonises with their everyday and is in that manner, syncretic. It contains and it layers this painting, even the single line of surf (which Thomas says is characteristic of the sea in these locations) helps in this function., although the patterning of colour is more impressionist than expressionist unlike the land. Patterns of dark and shade however create nuance around the interactions of the figures that are just complex and beautiful, ‘holy’ almost as relationships with people can sometimes seem.

And this is the more complex when the syncretic is deliberately invoked as a confluence of iconographic traditions. Thomas is excellent here and over many examples, of which I will chose two, which of course, being iconographic paintings require their titles, even if not given away by Gauguin directly.

Thomas tells us the standing figure in Parau na te varua ino (1892) is based on a medieval statue of Eve but in a Polynesian forested setting. However, the syncretism here goes deeper. The Catholic church utilized, as the Christians have since their inception as a belief-system, used the name of Gods from more ancient civilizations as the name of demons and evil spirits (Milton remember makes great play of this in Books 1 and 2 of Paradise Lost). Hence to Catholic believers inowas the name the Church encouraged Polynesian citizens to use of a ‘bad’ or ‘evil spirit, However, it was also used in Polynesian retellings of stories of their ancestral gods, whom were not necessarily, or if so not simply, wicked beings. The figure of the ino behind ‘Eve’ (who has already been caused to know and feel ashamed of her genital nudity and hence hides it) may or may not be the substitutes for the tempting serpent. Gauguin leaves that open, by also suggesting the serpentine motion in the branches of the tree above Eve and the dragon-like stump overlooking the ino.[10]

As Thomas says we do not know how much Gauguin knew of the meaning of the original ancestral Gods nor of the ways these had been appropriated by Catholicism but what is clear is that he renders the source of Eve’s shame, or even its ontology, for it is shame that bears a beautiful smile, looking round upon the viewer, It is a look that is very mysterious and we read in a way that does not encourage ideas of binaries of good and evil. Eve is a prototype of the Virgin in Byzantine thought and it is conceivable that the image of the Virgin and her Child, the latter carried in Polynesian rather than Graeco-Roman fashion, is an older matured version of the child Eve (the feet are similar and the splay of the hand holding the fabric cloth to her genitals is also like that holding securely the foot of the Holy Child riding her shoulder but asleep). Both Virgin and Child have a halo each. Thomas says that the picture was intended for a Parisian audience and can but wonder what both Polynesians and their Christian ministers made of the painting but he notes that, at the same period stained-glass windows showed a Polynesian Virgin, in line with Catholic syncretism as a tool of conversion.

Clearly the presence of two other women holding up their hands in prayer to the Madonna makes this perhaps even an orthodox syncretism, but I sense that Gauguin finds not just analogy but metamorphosis. What occurs in these images seems definitive of religious thought and narrative happening between different cultural versions of redemption stories. I find the imagery in the painting cluttered and claustrophobic, as if the vegetative edible plenty around the Virgin were meant to be spiritually meaningful too. Orana means ‘Welcome’ and it is possible to read the painting as propaganda meant to please the French bourgeoisie about colonial exploitation – in that Christ in the South Seas has encouraged ‘plenty’ rather than ‘poverty’. However, even if so, it is also possible that the fertility on show is meant to introduce new meaning into an over-hasty condemnation of sex and reproductive process in some kinds of Catholic teaching.

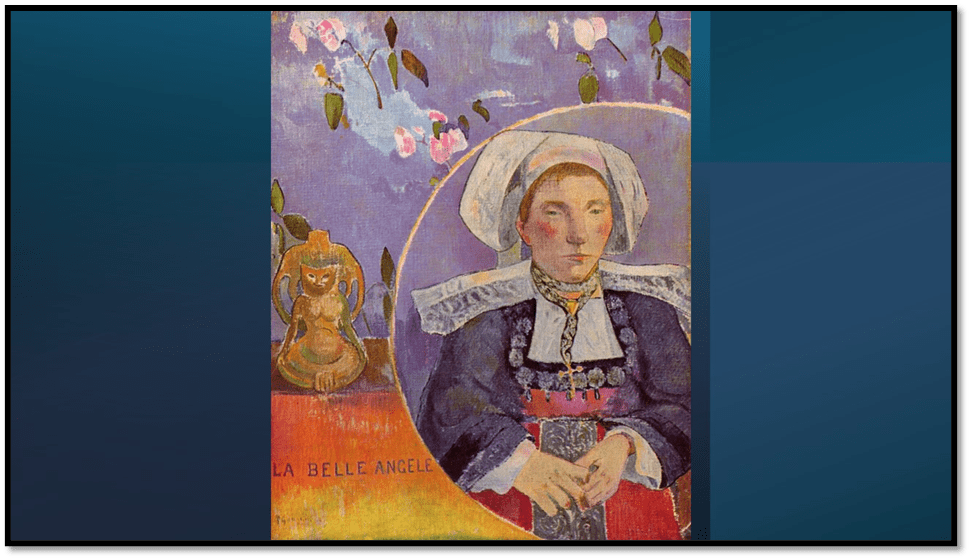

The wonder of Thomas’ book is that he believes truths contain contradictions. We do not look for what an artist or one group of artistic commentators find in paintings but for ‘ambiguities or ‘multiplicities of potential meanings. Thomas tells us he took this approach from P.J. Clark’s book on Courbet and cites it as epigram to the section of the book on Gauguin’s ‘WORKS: ‘It does not concern us whether the ambiguities I have pointed out were consciously or unconsciously devised: they are nonetheless there. This way of working extends into the representation of femininity more generally. Let’s look at two examples of images that have a kind of secular syncretism in mixing together what is Polynesian and what comes from elsewhere. See the following collage:

It is easy to be either condemnatory of Gauguin’s sexual relationship with Teha’amana (he boasted that she gave him nightly ‘blow-jobs’) with a girl he started living with when she was 13, without thinking of the expectations and the understanding of either consent or coercion in these communities before as well as during colonisation. Thomas has much to say that is not in DEFENCE of Gauguin but in an attempt to resist rendering Teha’amana as a mere victim, for when Gauguin left her she easily found another sustaining life and what she did, she did with the agreement with both of the female carers she recognised as mothers.[11] On the other hand, it is too easy to explain the situation away as cultural relativism. I think we have to accept both readings and our discomfort with each for both contradictory readings are truths. The painting is complex. The young woman holds a linen cloth in precisely the way we see Eve does in the painting referred to earlier, and finished a year later. Thomas believed that the West is so currently fixated on the sexual exploitation in the relationship to see the power that Teha’amana did have as a mentor to Gauguin on matters of local culture and its relation to traditions of land and belonging in notions of ‘home’ in Polynesia. She acted as a model of course and we could see that as an exploited position.

In Faaturama, Teha’amana is dressed as a queen or a person of wealth and status in the dress codes of the Tahitians at this period – the voluminous dress does not sexualise but give status, and Teha’amana appears to adopt a kind of sad reflectiveness in this that engages her further with the icons of home around her – the ornate rocking-chair and the Gauguin painting of her home on the wall. The picture oozes respect of a kind of independent womanhood that is not usually noticed in her portraits. Her hands, feet and face alone are naked, and these are all disengaged currently but capable of such engagement. There is no invitation to the ‘male gaze’.

Merahi metua no Teha’amana also is about giving queenly status to the figure, perhaps that is given away by the coconut leaf fibre fan which Thomas tells us would only be used by women of higher status and age than Teha’amana. We could rush then to saying the model is exploited for Gauguin’s purposes but I think Thomas must be correct in denying this in this painting, which refers to the two mothers, and the nature of Polynesian kinship and the role of chosen families in it that is implied by those two mothers, to show that Polynesian everywoman had much cultural heritage to bolster her self-esteem – in the ancestral gods on the wall plague behind her and the authoritative runes above her. This is a culture of word and picture. She is dressed as a contemporary Tahitian woman would be, again in a costume not designed to attract the male gaze but indicate status. The aim Thomas says is to show Teha’amana with ‘a whole assembly of ancestors that seem to stand behind’ her ‘and give her strength’.[12]

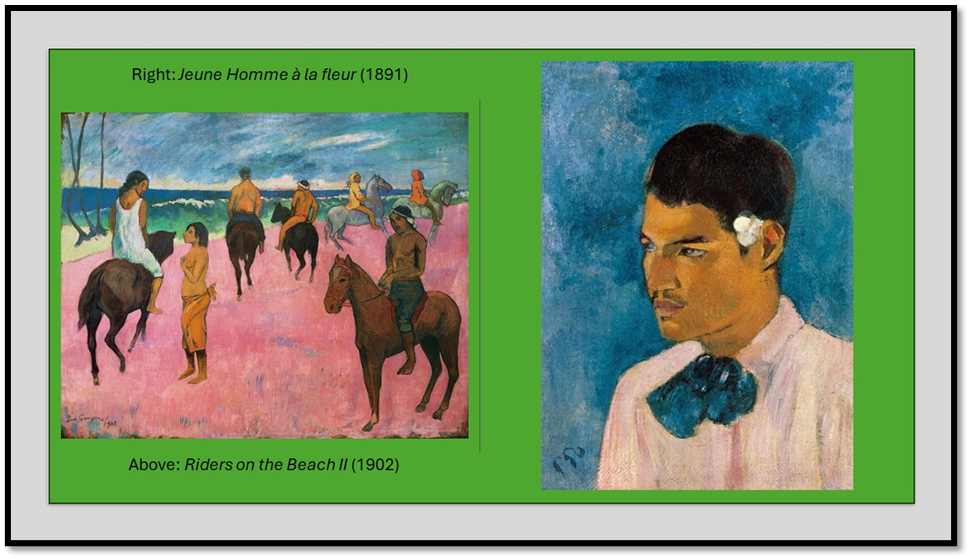

And another issue matters too, which Thomas shows he knows about but does not develop further in this book – the role of transgender discourse in Polynesian cultural life. Chapter 17 is perhaps the most extensive discussion of sex/gender discourse in the understanding of Polynesian cultures up to the present day and bears some interesting feminist Polynesian voices and historical research by curator Jim Vivieacre into third-sex identities, that was suppressed by Catholicism. The identities include the māhū of Tahiti and the fa’afafine in Samoa. The category of persons who were born biologically as male but who “live in the manner of a woman”, and it is often referenced in this book. It also hums through the various representations of men and women in Gauguin’s career where making sex/gender decisions about models is not emphasised as primarily or necessarily important.[13] Such an idea seems important to me in some of Gauguin’s most beautiful pictures where he attempts to capture either indifference to gender, where, for instance, customs of display can be shared by men and women, like wearing flowers in the hair, and in activities like riding horses on the beach. In the first version of the Riders picture there were no women. The second also contains hooded figures more like supernatural Polynesian figures than how either men or women appeared. So even in sex/gender roles, being mysterious’ still mattered.[14]

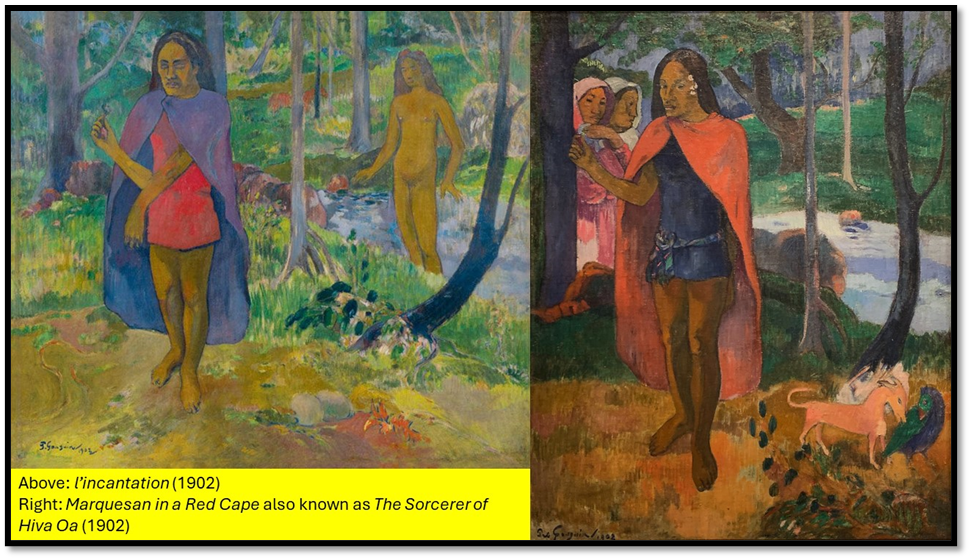

Mystery is singularly important in two paintings which show a person gifted with magic in the two contemporaneous paintings below:

Thomas makes it clear that the sex/gender of the person with supposed magic powers, approached by suppliants from behind, is not knowable from the picture alone, despite the fact that some attribute the character to a specific male character known to Gauguin and possibly a shaman. Thomas explores the ambiguity of the sex / gender markers of the figure and you can read this in him.[15] He writes in particular: ‘Marquesan men seldom wore their hair long; to do so would imply identification as a māhū, a man living “in the manner of a woman”’. In no way is the man identified by art historians a ‘look-alike’ for this shaman, who was actually rather butchly well-made, but Thomas is clear that ‘Gauguin would certainly have known real māhū in both Tahiti and the Marquesas’.[16]

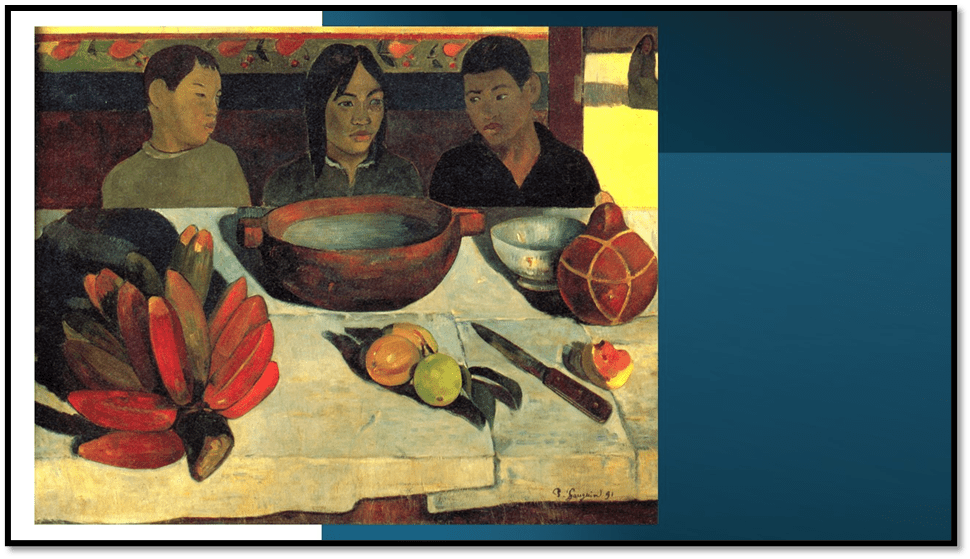

Whether this resonates through other pictures cannot be determined, such as, for instance that wonderful painting Le Repas (1891).

Thomas quizzes this picture in terms of its representation of everyday Polynesian ceramics and their syncretic associations to contested religious cultures. But the piece is interesting too in that, for us, the only sex/gender markers are the contrast of long and short hair previously mentioned. The child centrally placed may by this marker be a girl but we can see that this cannot be assumed and that the child may already be identified as non-binary. Moreover, this surely creates lots of interest about how these figures relate to the still life before them. A bowl is a ‘sacred gift’ and we see it, as Thomas says, also in la orana Maria (above). [17] However, in both it is also associated with femininity, either as food bowl or offering to the Gods. That this bowl is placed before the long-haired figure may associated a link to femininity but does not guarantee sexual category. My feeling is there is mystery and contradiction here, that is duplicated in the potential to sexual symbolism in the still life – a pointed knife and bananas are phallic but the gourd is positively hermaphroditic. What this tells us about the nature of looking and seeking meaning is complicated

Meanwhile whatever Gauguin’s relationship to other European settlers, he very much frames them as cut off from Polynesian context, except in appropriation of objects.

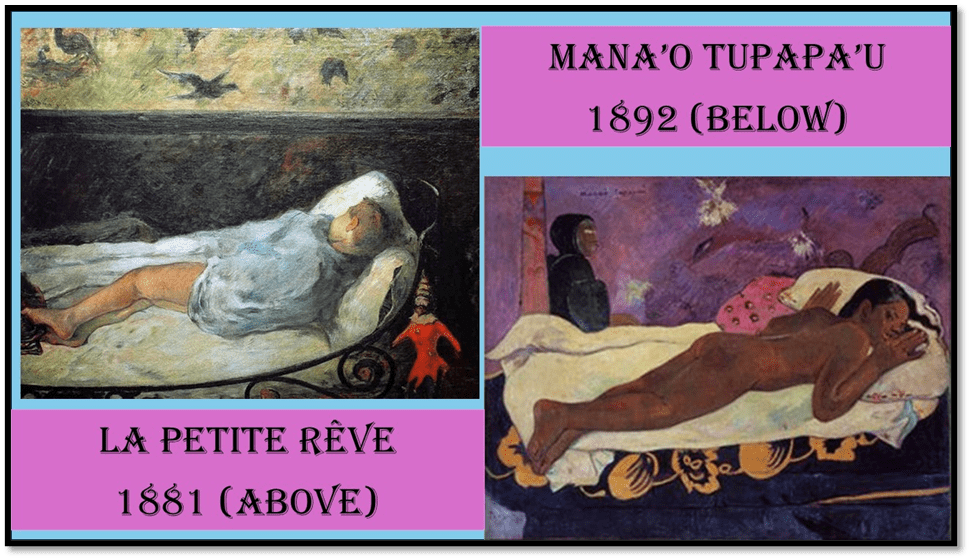

We cannot leave Gauguin though without worrying out the sexualisation of young girls in his paintings. Thomas raises the issue around two paintings collaged together below:

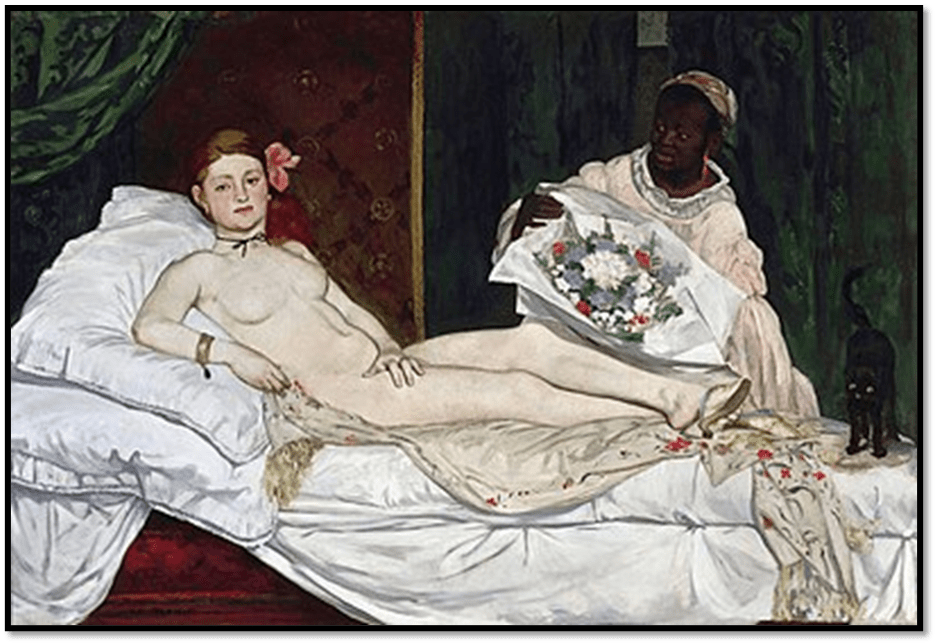

David Sweetman reads the painting La Petite Rêve as evidence of Gauguin’s ‘incestuous lust for his daughter Aline’ because she adopts a pose comparable to Manet’s Olympia, the portrait of a high-class courtesan like Zola’s Nana. As Thomas says, however, there is no eroticization in the portrayal, even of the subtlest kind. This cannot be used to see Gauguin as a paedophile. In the period he tells us, of this 13 year old such as Teha’amana was, could marry in the USA and some parts of Europe. In Tahiti, 13 was a marriageable age, though we do feel really ethically uncertain about him checking her venereal disease that she might pass on to him, when he already had such a disease and could pass it to her which he discounted that she had an interest in.[18] Thomas argues that similarly Mana’o tupapa’u (1892) was not an erotic picture but of a girl confronting fear of the unknown generally. I find it hard to go along entirely with Thomas. He invokes the manuscript notes on the painting to show that its primary interest is the containment of a Polynesian girl child’s fears of her ancestral duties, represented by the impersonal ino that hovers behind her. Thomas argues that anyway double-truths may be operating here but not hypocrisy. He does not however explain why in the manuscript notes Gauguin puts a ring around the model’s anus in his rough sketch of the design, and I think the issue of sodomy as an area of exploration cannot be ruled out, although possibly overdone by some critics he cites. Obviously much more would need to be said:

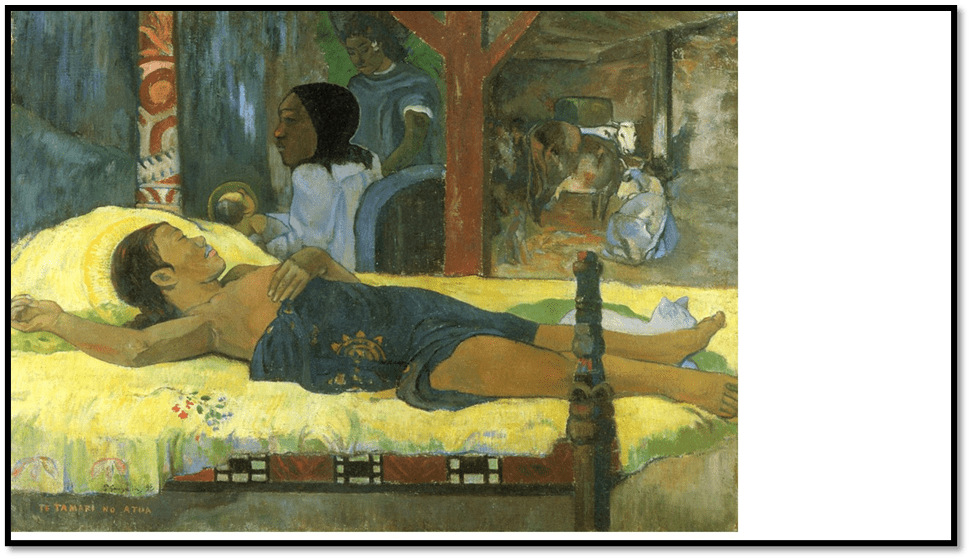

The Olympia theme resonates throughout Gauguin’s oeuvre however and it is certain that people become very nervy when the model is face downwards though potentially sexualised. I think I do too but won’t explore it. The famous painting Nevermore (1891) needs no reproduction and is clearly in the family of Te tamari no atua (1896) – see below:

This is another Madonna and Child picture with haloes of fully syncretic ambiguities of meaning as explored by Thomas.[19] Thomas argues that the painting is respectful rather than just admiring, as with Olympia. One is in awe of the woman. His interest is in her absorption and unawareness of a viewer: ‘Both her fatigue and her strength are somehow palpable; unlike so many of Gauguin’s subjects, she is fully absorbed in her own state, unaware of and indifferent to any viewer’.[20]

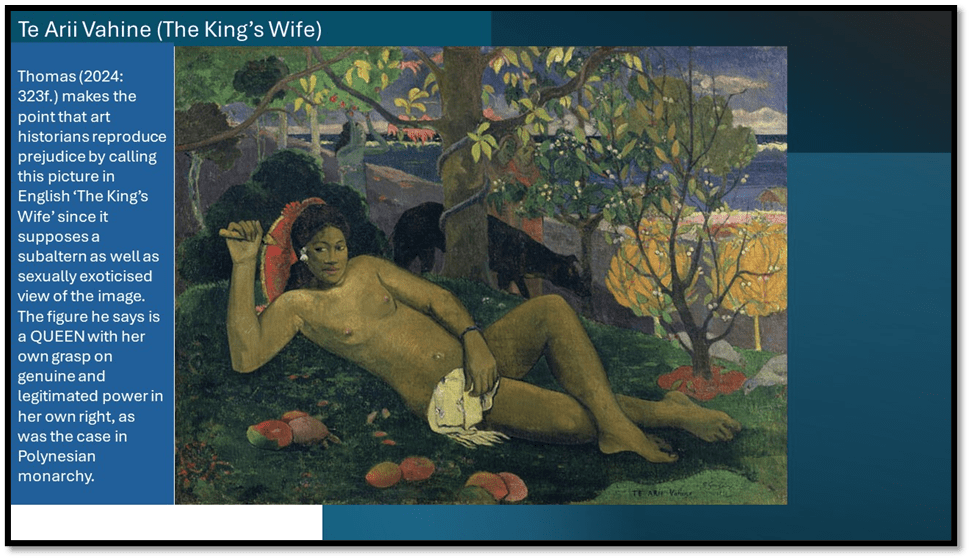

Let’s end though with the queen of Gauguin’s Olympias, Te Arii Vahine. This woman is NOT ‘absorbed in her own state’, for her state is precisely that of a woman to be seen and evaluated – but not necessarily sexually, whatever the recall of the courtesan, Olympia.

Gauguin’s model is a kind of mother of humanity – a Queen of all of her subjects conceived as if they were her progeny. Thomas sees a reference to Eve in the coiling in the tree branches (a serpent?) yet he dismisses that possibility as a primary response to the painting. Instead he looks at the way in which female power is thought about in Polynesia, or was in its history before now. This is not ‘a king’s wife’ but a queen in her own right. It may westernise Polynesia with the use of the Olympia analogy but he argues this women is not for sale as Olympia is, even if to only those she likes herself, but tries to capture a reality of Polynesia a step away from ‘patriarchy’ towards ‘an order in which women had autonomy and power’. You need to read the passage to see if you are convinced.[21]

I have never read a biography of an artist so fruitful and educative as this. It is about genuine humane learning. Read it. Buy it in hardback if you can. It is a beautiful book.

By the way, here is Manet’s Olympia to remind you.

I may report back after Sunday when I see him speak.

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Nicholas Thomas (2024: 316,312, 313 respectively) Gauguin and Polynesia London, Head Of Zeus Ltd

[2] Ibid: 20

[3] Cited ibid: 210f.

[4] Ibid: 195

[5] Ibid: 110

[6] Ibid: 105

[7] Ibid: 141

[8] Ibid: 141

[9] Ibid: 188

[10] Ibid: 200

[11] See ibid: 240ff.

[12] Ibid: 256f.

[13] See ibid: 383

[14] Ibid: 410

[15] See ibid: 354, 358.

[16] Ibid: 358

[17] Ibid: 266

[18] Ibid: 31

[19] Ibid: 325f.

[20] Ibid: 328

[21] Ibid: 322 – 325.

One thought on “This is a blog on Nicholas Thomas (2024) ‘Gauguin and Polynesia’, in preparation of seeing him at Hexham Book Festival, Queens Hall on Sunday 5th May 2024, 11 a.m. Brilliant on anthropology of transsexuality. ”