We do not need a list if we consider poets the ‘unacknowledged legislators of the world’. This blog takes an encounter with the reading of a rather wonderful current poet, Kathleen Jamie at the Hexham literary Feastival, to try and explain what I mean, if (as is my wont) obscurely and, in another way, darkly. To start of the writing though I found on the internet a rather good explanation of what Percy Bysshe Shelley meant by saying ‘poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world’ by Francesco M. (the abbreviated name of a tutor on the webpage the writing is taken from). Here it is:

In his Defence of Poetry P.B. Shelley claims that poetry ‘is connate with the origin of man’ and man ‘is an instrument over which a series of external and internal impressions are driven’. Shelley demonstrates the crucial role that language plays in the interpretation of impressions. He believes that the metaphorical power of language marks ‘the before unapprehended relations of things’ and then perpetuate their apprehension, until language transforms these relations into words, which represents them through images ‘for portion and classes of thoughts’. Shelley’s account of poetic language seeks to find an order to the chaos, which, possibly, Shelley sees in human society: a chaos that only poets can fathom. Therefore, poets’ enhanced poetic language can re-institute an order to human society. For example, Shelley maintains that poets can institute laws and create new materials for knowledge, determining the role of poets as legislators. In calling poets ‘unacknowledged’, Shelley challenges the critic Thomas Love Peacock, who in the Four Ages of Poetry believed that the progression of society caused the deterioration of poetry. Shelley utilizes the Defence of Poetry to suggest otherwise and to condemn, covertly, a society that underestimates the importance of poets and their contribution to the progress of society. Therefore, poets are ‘unacknowledged legislators’, because their role in the progression of society will not be publicly recognized.

In brief and with my slant, poets translate the chaotic impressions of a multitude (the Many) of such impressions that impinge on the human consciousness, translating them into an order that that is inevitably the order of justice and fairness amongst the diversity of things rather than in the interests of a ‘Few’: the currently rich and powerful of an unjust status quo. Of late, this view has taken a pounding for it imagines that poets can see through the murk of layered injustices and their consequences to some ideal order. Shelley may underestimate the fact though that poets when acting working with language are also a gauge that measures that the world (qualitatively, rather than quantitatively) that they reorder by virtue of their refined grasp of the function of language according to some fairer principle. Up to yesterday, I still believed, though, that poets always move on beyond the disorder of chaos reactionary forces imposed as the world’s ‘reality’. This was a consolation.

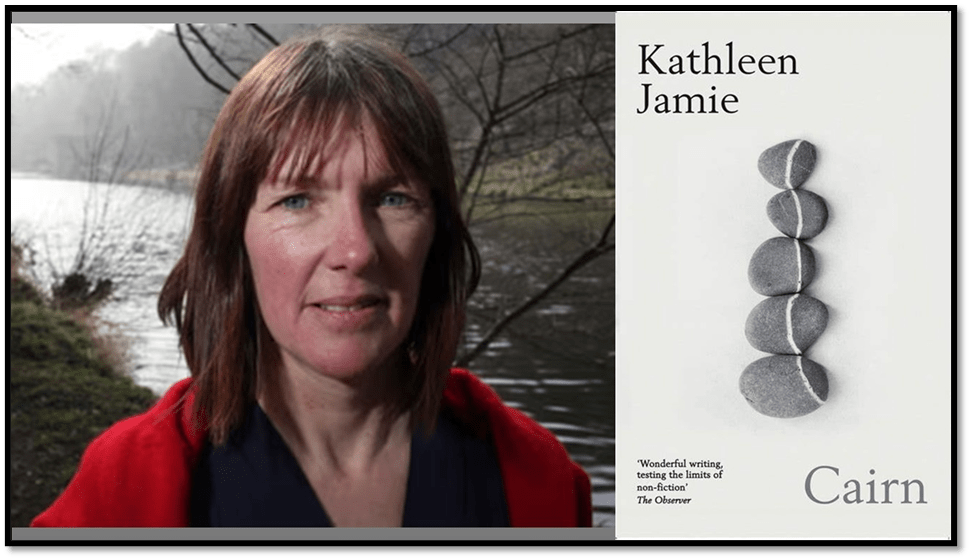

As a consolation, it is similar to that poets have found in applying their imagination to the function of ‘nature’ as a thing distinct from the world of a corrupted humanity. Yesterday, however, I saw Kathleen Jamie, a powerful poet and currently Scottish Makar, and my assumptive world shattered in the manner that Ronnie Janoff-Bulman in 1992 , and thereafter the grief therapist Colin Murray Parkes tell us ‘trauma’ shatters assumptive worlds. It was a disturbing experience. I write this to try and address it, and will use the remnant of a blog which I was trying to prepare about seeing Jamie to do so, righting my over-confident readings so destroyed by Jamie’s every word and gesture, showing me the true record of how her latest work, Cairn (2024 but a book not yet formally published), in the name of poetry and poets registers so powerfully the fragmented disorder of the world without putting it back together again. It is, as Jamie showed a book without consolation. Yesterday the impression of that lack of consolation nearly broke me. It fuelled dreams trying to put my assumptive world back together to ensure a workable continuation. I am not exaggerating here, though I cannot convince you otherwise – I am not enough of an artist.

Jamie said that the world in which any belief in he ability of nature and the natural world to restore itself after the depredations and rape of it by humanity no longer holds. Constancy in climate patterns are broken, vast numbers of species have moved to a larger and faster mass extinction irreversibly, even species we once denominated in human confidence ‘common’ such as the curlew (or ‘whaup’), the subject of one immensely moving piece The Whaup’s Skull, which Jamie read and made me see again though I had tried to understand while preparing my blog in the morning just preceding the event she spoke at (2.30 p.m. 27th April 2024 at the Queens Hall in Hexham).

I tried to ask a question about my feelings relating to that piece, but my question collapsed. The poet said,’What do you mean?’ and my illusions sank deeper as a result of confronting the lack of certainties that hearing this piece read had reduced me to. For such break-ups in consciousness, 7we must be grateful to poets for sharing their own significant breakdowns in humane confidence and consolation in justice. Obviously, what follows rewrites what I wrote that morning considerably, though using some of the same wording, where it matched the requirements of the present piece to restore to me something nearer to sanity on these questions.

But let me start off with what I had close-typed in Word already, even its title.

‘We draw the graphs, our generation. We are everywhere surrounded by those down-curves out of abundance into scarcity, even into extinction. … The sobbing trill gliding into silence and bone’.[1] This blog is a preparation to see Kathleen Jamie, reading from her new collection of hybrid prose and poetry, Cairn, at the Hexham Literary Festival in The Queens Hall, Hexham.

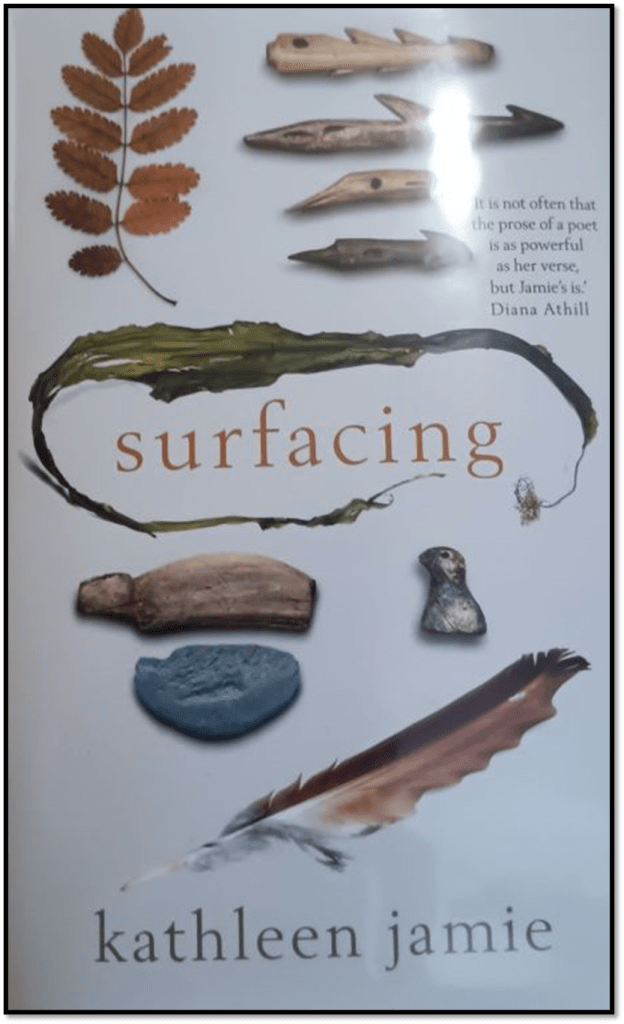

I referenced Jamie’s beautiful book Surfacing in an earlier blog at this link, and I sensed there a bold geopolitical stance. And although singled out by John Berger, as “a sorceress of the essay form”, her essays are, she said in 2012, not directly political. She is aware of this but answers questions obliquely about it, as she does to Sarah Crown, though a long time ago now (12 years).

This engagement with the political side of life is never far from Jamie’s conversation, but its presence in her work is less explicit. When I ask whether politics is important to her writing, she turns the question back on me: “Can you tell from reading my work that I have any political awareness?” Well, yes, I say, certainly – but put on the spot, I can’t call any specific examples to mind. …She nods slowly. “I don’t think, when I’m writing, ‘now I’m going to write a political tract’, but … I do think that part of the reason for Findings‘ success, for example, was that the land and landscapes were described by an indigene. Not by someone arriving as a tourist – or crucially, as an owner. On the scandalous business of land and land ownership, especially in Scotland, where 80% of the land is owned by 10% of the people, I feel I might be striking a tiny blow: by getting out into these places, and developing a language and a way of seeing which is not theirs but ours. And when we do that – step outdoors, and look up – we’re not little cogs in the capitalist machine. It’s the simplest act of resistance and renewal. This isn’t new, of course, but alas it’s still necessary. Never more so.” [1]

Indirect in politics then, Jamie has baulked too as being named as a practitioner of nature-writing. Jamie told Patrick Barkham in an interview in 2019 that she hated that label. Here is Barkham’s assessment:

Jamie is not a polemicist but hopes that her writing raises questions. She does not like the “nature writing” label. “Publishers and bookshops want a wee ticket to put on it. That’s not serving us well.”

But she believes such writing can provide an alternative to mega-consumption. “I would like to think of nature writing as a nice little retreat. I don’t want it to be on the frontline. I want routes not to the barricades but to a more thoughtful way, a kinder way – more compassionate to ourselves and other creatures. “I’m not an activist. Maybe I ought to be but it’s really not where my talent lies. An activist knows what they want and they work out how to get it. More ‘creative’ people like me have no idea what we want until it’s done.”[2]

The attack on modernity she makes though, as expressed by Barkham art least, is on one of the salient features of capitalist production, however – the encouragement to over-consumption and the building into the commodity the appeal to consumerist desire through advertising, branding and surplus packaging bearing the sounds of both. In Cairn, this is exemplified in the ‘plastic bags’ consumed by a whale who suffocated as a result bearing, still fresh as the day it was printed the word FRESH in relation to the gutted fish it once contained for sale.[3] At Hexham she described her own work, if I remember the phraseology correctly, which I may not, as a way of looking at ‘nature, culture, and travel’ all together and as they overlap rather than as ‘nature-writing’. This is illuminating.

I found it particularly illuminating in terms of her iteration of the term, twice at significant places (one at the very end) of the agency of capitalism in the results her writing manifests in nature, culture and the reasons people travel: ‘it’s capitalism, ya eejits’.[4] This features apparent in her prose, poetry and prose poetry concern, let’s say, these ones:

- The making of tangible things for use or consumption or both into commodities;

- Over-stimulated or excessive consumption if commodities;

- The dominance of display and advertising over clear description as a means of metamorphosis of product into commodity;

- A high degree of inappropriate desire for that which commodities in themselves cannot in truth supply;

- A reason to overvalue the present over the past and future and a disregard of the effects of rampant waste in excess production;

- The purchase of over-wrapped basics in inflated markets whilst not achieving the means of meeting the needs of those unable to buy even basics.

If this is what is meant by mega-consumption, Jamie is on the side of those antagonistic to the capitalist status quo. In Cairn, she remains ambiguous nevertheless about activist politics, looking backing back in her essay The Handover to a politics of the friends of her youth in a ‘tenement flat in the west end of Glasgow’ (an area populated by students) as they decide on slogans for banners.

Clearly the poet’s persona in this piece admires them (these activists from the past – and the women of Greenham Common) but also by comparison shows their model of politics to be a failed one. In the piece Jordan Street, she thinks back to a shared house with young friends and remembers a young revolutionary man, Jez, she would have been happy to bed and, indeed, now dreams that she is doing so: ‘I wouldn’t know him now if Passed him on the street. He’d be a pensioner, and no revolution yet’.[5]

She paints a picture of our present-time in politics as elders like her at sixty when writing do their ‘handover’ to the young as a highly compromised clinging on for survival, the disaster of climate change and ecological extinction being already upon us. Her son accepts on the balance of things, when questioned, NATO membership and hence nuclear deterrence policy and lives for moment to moment in fear as ‘History unfolds’: ‘He said, “I’m going to live through it”, and it clenched my heart. I thought: Please do. Please, please do’.[6] The politics of The Handover are tragic and pessimistic. We make a plea for hope rather than feel that hope. After all, as a friend is reported, in this very essay, saying to her: ‘“for this generation, the Bomb has already detonated. Climate change is actually happening –“ ‘[7]

But in this piece, still the concern goes on about the decline of life in its grand quantifiable totals. But let’s look at how Jamie presents it, in the curves of a grand tragic metaphysic where the quality of our feeling matters more than the accumulation of statistics of consumption and species extinction. Here is the quote from the title again a little more fully:

We draw the graphs, our generation. We are everywhere surrounded by those down-curves out of abundance into scarcity, even into extinction. The ‘common’ curlew, as the old books have it. A bill like a long nib that could write its own epitaph. The sobbing trill gliding into silence and bone’[8]

Like nature-writing, now the domain of white middle-class men as she told Barkham, men replace quality of feeling entirely with statistics and ‘facts’. This has a lot to do with patriarchal models of writing that linger over rights of entitled ownership than the empathy one endangered species should have for each other about which she discourse in interview with Sarah Crown as quoted above. If we look to the ‘natives’ of ‘nature’ we will hear it in their songs. She imagines them launching (and indeed writing) the elegiac heard in nature (whether there or not) probably because they are increasingly in the natural world, whatever that phrase truly means, no longer ‘common’ and are, many of them, near extinction. Thus, as this piece of writing indicates, the ‘common curlew’ is no longer common, whatever we name it, but a species turning into bone and absorbed into the stone of geological time. There is resistance to this happening, as Isabel Armitage writes in a good WordPress blog post. But ‘endangered not ‘common’ is what the curlew now is:[9]

We are trained by literary establishments to be suspicious of the kind of projection of anthropomorphic emotion into other species, such as the ‘sobbing trill’ Jamie hears and the rhythms of sentences that decline more effectively than ‘down-curves’ in graphs into ‘silence and bone’. And what of the fact that declining signature is seen to write its own elegy: the curlew’s beak being ‘like a long nib that could write its own epitaph’. That the curlew is said to write in the process of extinction into non-being, takes further a mere metaphor about the shape of its beak used earlier in the piece describing it as ‘a long calligraphic descending curve’, like the graphs of numeric decline to be described later. But this is not the only time when the meanings and harmonies of nature’s decline write themselves in the book: a storm over a ‘green island’ in Shipping Forecast falls into poetic or musical rather than statistical ‘measure’ : ‘a trio of flashes, then a long pause, a signature written on the wind’.

But that nib-like bill matters too because once a man wrote about curlews in nature, though he had no need to worry about the bird’s death as a species or of nature losing its regenerative power. As Jamie scratches out, with a pen, her thanks for being gifted with a skull of the whaup, she wonders if what she writes is ‘a sentence Gilbert White might have scratched out with his nibbed pen’. White never thought nature would let him down, though he often let it down with sometimes more regard for its dead than living specimens. His example makes Jamie’s writing more conscious that she should imagine what the whaup’s own feelings might be about its extinction. How the curlew write with a beak like White’s pen, or ‘quill’, as she wonders it might be.

I noticed too how the phrase ‘those down-curves out of abundance into scarcity, even into extinction’ I quote above is reflectively echoed (to my ear at least) in a poem in the collection later: Once Upon a Hill’.

You could lean against the tree and watch the river

become a firth, widening over miles.

You could watch it as it bore away not just

the winter’s rain – goodbye!

goodbye! -but whatever one needed to lose.

And that was plenty, but the tree seemed to insist

upon something further: beyond

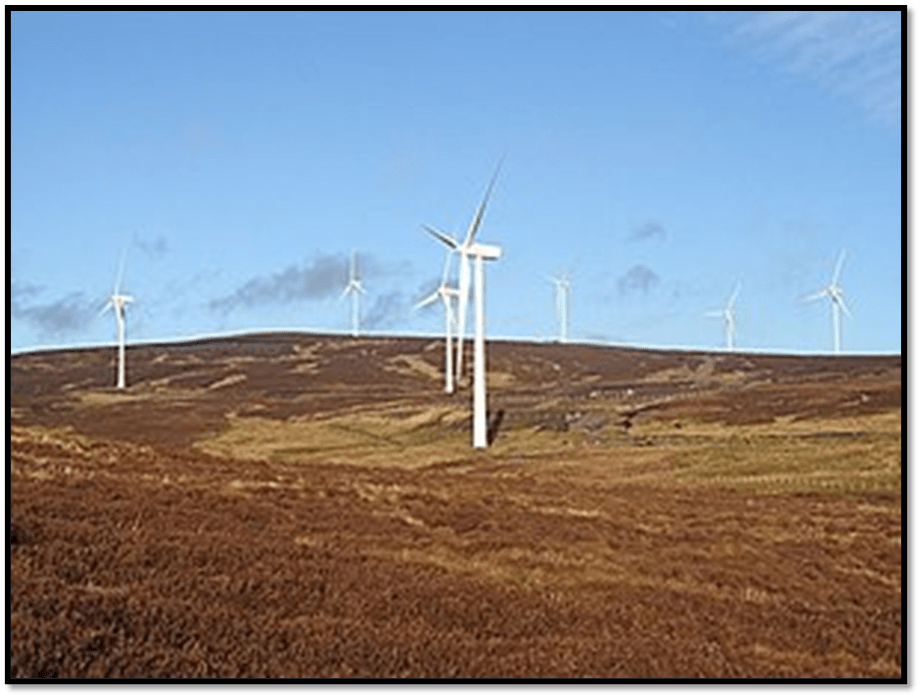

the Braes of the Carse and wind turbines, beyond

even the mountains: a gleam of – what?[10]

It can be argued that there is no echoing going on between these two domains of language. The ‘plenty’ in the poem is not exactly what is referred to as ‘abundance’ falling into scarcity or extinction. After all in the poem the reflecting persona ‘needed to lose’ its plenty’ (precisely because it didn’t need it whether it thought so or not) but the tree illustrates (once from the plenty of wide forestland in Scotland itself but now isolated on a hill, that in losing what has become a burden to us, as over-abundance can be, we will lose something else, the gesturing to a ‘greater glory’, the secular equivalent of God found by Wordsworth, for instance, in the imagination cooperating with nature, or pointed to by an icon of the Virgin in the Byzantine monastery of Panayia Porphyra (the All- holy in purple – the acme of glory religious and secular). For even she nowadays has eyes that ‘look through us, into the void beyond’. [11] Both tree and Virgin aspire ‘beyond’ as symbols but they look into emptiness, ‘even into extinction’. And it may be what is extinguished is anything of value in human and human behaviour.

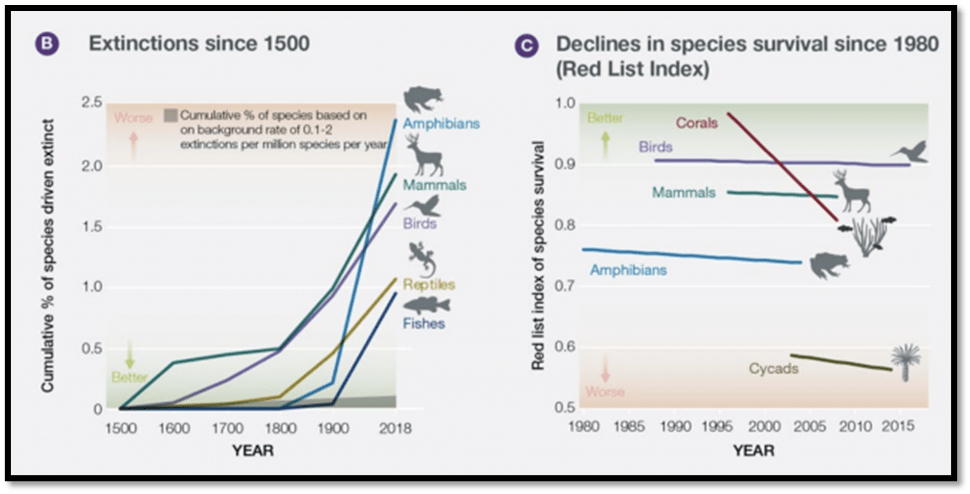

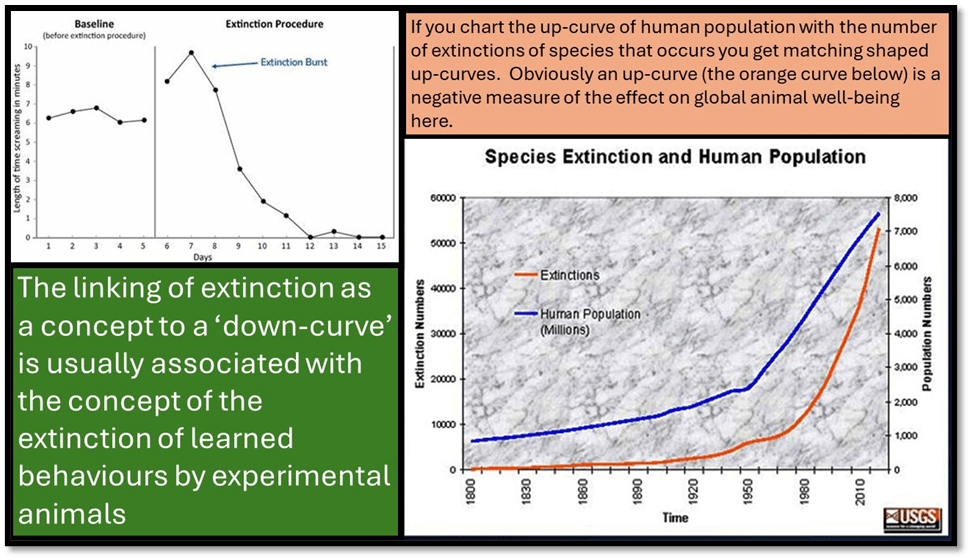

I am wont to take references in books a long way but I was intrigued with Jamie’s reference to ‘those down-curves out of abundance into scarcity, even into extinction’, for try as I might I could not find extinction represented graphically in ‘down-curves’. It was this that my inept question to Jamie tried to get at. But no wonder she said ‘What do you mean?‘ I could not have said in truth. But I noticed before I went to the event and after reading Cairn that, in fact, the graphic illustration of extinction (based of course on the search done by Google using ‘species extinction curves’ (try it!) amongst its images, is apparently most commonly represented in up-curves, not down-curves, showing the rate of extinction of whole species. Of course to the politicised imagination, it jars and hurts to see extinction represented as something moving up. But actually charting declines does not show as ‘graphically’ (so to speak) the tragedies involved, though it does show them.

The only examples of dramatic ‘down curves’ was of ‘extinction’ as a concept in psychology. It denotes in behaviourist psychology, as an experimentally demonstrable characteristic of learned behaviour after withdrawal of the stimulus that promoted the learned behaviour (these curves are important in studies of animal learning by direct and indirect association promoted by Pavlov and Skinner respectively. See my collage below:

Graphs that illustrate extinction over shorter periods than centuries of years, don’t, that is, often do that using down-curves except when in illustrating the fact that when a stimulus to a behavioural response is removed, behaviour we may have believed natural begins to disappear. In a sense that is what Jamie’s work illustrates, although she need not, and probably does not, see it like that. It illustrates that the extinction of human sensitivity to the loss the consoling nature and meaning of nature to the human imagination (of what makes for glory in the world, and in ‘nature’) is a behaviour and trend of thought ITSELF being LOST, being extinguished as a behaviour. And with that loss will go the will to act politically to mitigate it or to do so with too much compromise that ensures we will not reverse the declines, in whatever way. Take, for instance, the ‘wind turbines’ at the ‘Braes of Carse’ , in the poem Once Upon a Hill (the relevant piece is cited above): they represent for most people the most that can to be done to mitigate global warming. But are they a sorry excuse for action? Most RSPB environmentalists now recognise that wind turbines, as huge mechanisms turning regardless of anything high in the air, are a threat to bird life themselves.

But I think Jamie does go deeper in promoting in poetry a behavioural reawakening of empathy and action for nature. It is just not by the mouthing of slogans like the protest marchers in The Handover; slogans like, ‘There is no Planet-B’. At this event, she said that, in truth, she has lost all belief she once had that nature will right things of itself – the hope that animated Wordsworth and other Romantic poets when they looked at mechanised industrial life. The relevant words are in Cairn, but heard from her – so deep was the authenticity of expressed feeling projected to me at least, that they seemed irreversibly devastating of the hope one has for continued existence. Extinction and mortality play dark games, for if a Cairn is a guide to our path like the ‘leading lights’ at the head of the Scapa Flow, it is also a Memorial, reminding us that time is loss and not merely human loss.

my every stone

a conscript, never asked

if they wouldn't rather remain

cradled across the land

remembering deep time?

I, we indicate

your places of disaster,

our dialects hushed:

mica-schist, feldspar, frost-shattered quartz.[12]

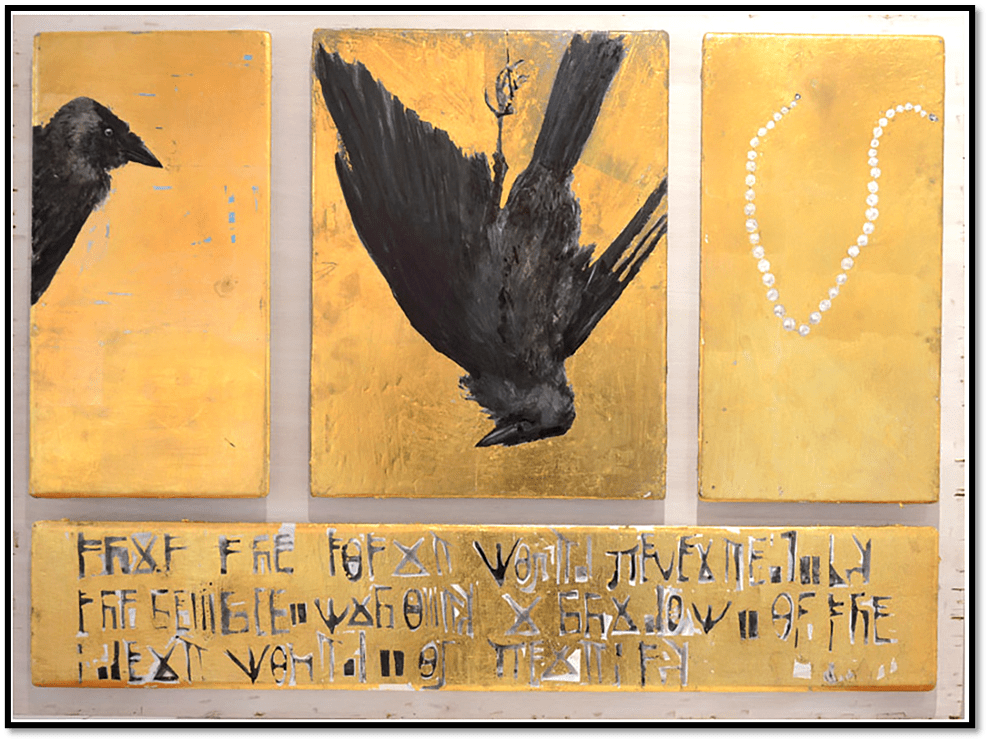

Losses vary by the durations and periods of time they speak about in the collection, most notably in that fine poem Corvid which deals with the difference a letter makes in defining human vulnerability to loss and referring to the period of lockdown from a disease believed to be released perhaps from the same causes as global warming – from COVID to CORVID, from sit to SHIT, and from WINDOW to widow featuring in particular the life-illustration of artist Julie Goring. Read the poem as you look at Julie’s CORVID art (13):

Julie Goring Flying Into Frames: Source: https://artmag.co.uk/julie-goring-flying-into-frames/

Understanding deep time is our only recourse in these days of the final end of ‘natural consolation’ and that time is, as the John Berger epigram reveals, the time experienced by stones not life forms. That is the meaning of the lovely piece Quartz Pebble, which recently surfaced object might be as well appreciated worm on a necklet for a minute’s show, decorating a Neolithic grave, or ‘thrown away’. (14) It isn’t that time is comfortably relative, we need as a species (possibly one due for extinction if not yet). We don’t believe that ‘a natural cycle of which we are part’ will save us, since as Jamie says in the Prologue, which she read at Hexham, no child born with the last thirty years ‘can believe that the natural world is so resilient’. Of course, she adds when we say ‘save the world’ or us’ all we mean is ‘”preserve the conditions of life as we know it, and all our fellow species, despite our depredations”‘ .(15). Another previously unknown form of life may be nature’s way – no consolation to us but perhaps what we deserve.

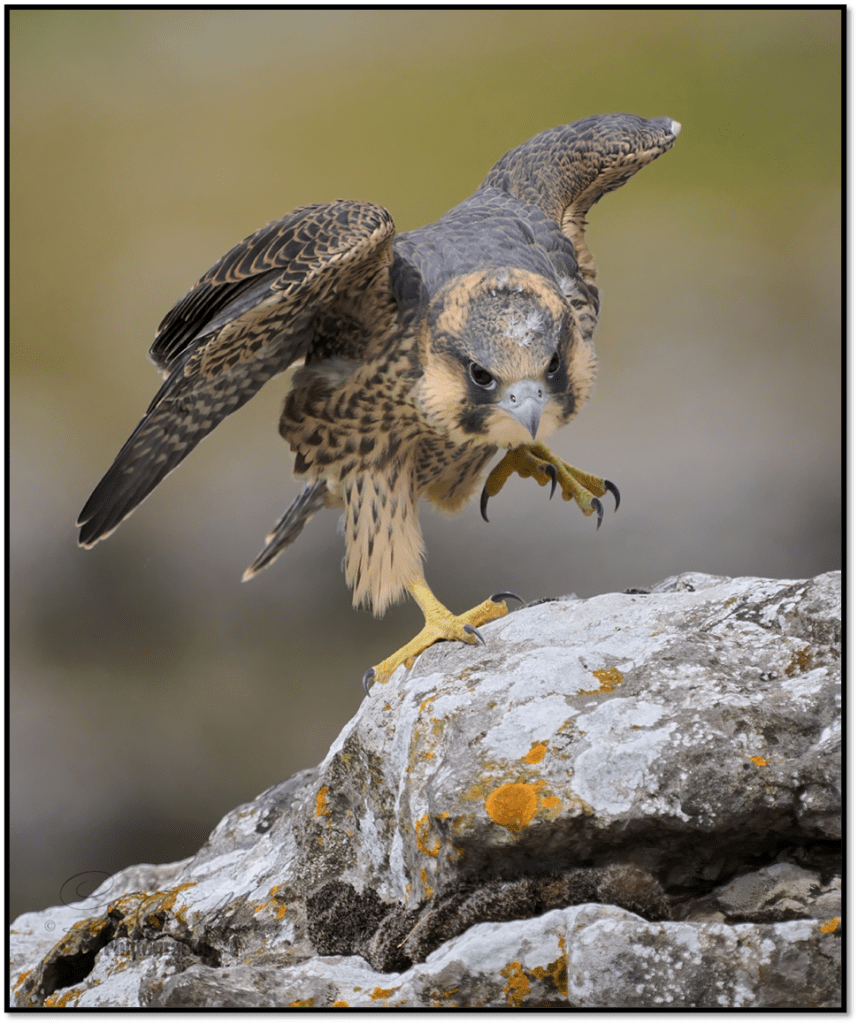

At Hexham, Jamie poke of believing in the cyclical nature of experienced time and, in the poems, time is seen, felt or inwardly experienced through the mediation of language as both circulating and progressing onwards, but beginning and endings are much more complex. The images of the motion of time are natural, cultural and to do with travel or transport – the motion of wind, rivers, webs and the motion of a spider within its web, but also of cultural activity in humans like writing, tracking, imagining the staging of life-spans and mortality and so on, the most beautiful example to my mind being the prose poem, Peregrines. The watcher watches as the year declines and the sun is in long slant, therefore fully ‘clear the hill’ against which the flight is seen. The pair watched may not be those expected,the ‘quarry pair’. The piece is a beautiful evocation of losses that are usually the subject of natural cycles. The sun will rise higher again, the days be and feel longer, but sometimes the losses and substitute replacements, in this collection of ‘deep time’ where peregrines may disappear forever: ‘In time the peregrines disappeared and a buzzard arrived, hanging with folded wings like an anvil in the air’. In the hint of a final ‘disappearance’ in longer, but not as long as we once thought, of endangered peregrines, the watcher is left ‘unsettled, sensing the raptor nearby’. (16) For the raptor is not the hawk but apocalyptic time – apocalyptic at least for humans.

Endings and beginnings are the stuff of human constructions of reality as Aristotle, in relation to art form, said, The Night Wind promises you tomorrow’s beginning (‘- now you can begin’) only in the dark truth that ‘Your dead stay dead’. (17) Yet backward moving times is a necessary illusion, one that cairns permit in the memorial function, even amongst couple ‘dredging’ up the mud and beauty too from past life together.(18) The pace of time can be measures as in species extinction curves but pace like duration is subject iun humans to imaginative metamorphosis and can be a matter of feeling, as in that jokey piece named after a cliché, Fullness of Time. (19) Even the pace of a mass demonstration – a march – of human resistance shows that. (20) Next to all that in the piece are elements of that human construction called ‘clock time (actually harmonised for the benefit of the administration of industrial scale railway travel) which is “ticking away” for Jamie’s son regarding climate change just as the ‘oil ships turn like slow dials on the tide’, irrespective of the deeper time cycles of whale migration.(21)

One theme of Jamie’s is that time must be feminised, by which nothing biological is intended though biology is involved. She insists women experience life in cycles as an offshoot of reproductive function but the ‘natural order’ they follow is contingent on many socio-cultural factors and hence Jamie gives thanks it was so for her. (22) She said something like this to Barkham in 2019:

Women cannot divorce themselves from their life stages, she thinks: “It’s a bit silly to pretend that the complete chaos of family life is not determining what you can do. What I would like to think I’m doing is insisting on the validity of women’s experience through different phases – young motherhood, older middle age, hopefully old age – so you have a sense of a woman’s life and what you might call deep time.” (Barkham op.cit)

Men are more functional – the world was constructed in patriarchy both to name things ‘lower’ than they in the hierarchies they also constructed and have the right to kill them. Jamie discusses this with a male friend and implicitly whilst visiting ‘Bergen’s Hvalsen’ [Whale Hall] in the piece named Plasthvalen (the plastic whale). They note ‘Cuvier’s beaked whale’ : ‘Cuvier, the French naturalist who first described extinction, as an event’.(23) Pushed to define feminisation in this volume I would say it was the greater positive evaluation given to ‘wee things’ rather than grand and grandiose things: its key poem is Glen.

(What’s too wee?)

Voice of a grouse, somewhere on a hill. Voice of a whaup. Falling asleep to the river sound, ….

Too wee, Too wee-wee-wee, what’s too wee?

The bird itself? The river whose winds it followed downstream at speed, …

Me? us? Our hesitancies? The scale our ambitions?

our response to the times?

Re-evaluation of size and abundance is needed to reverse ecological time. The book of my youth was Schumacher’s 1973 Small Is Beautiful: A Book of Economics written as if people mattered. It feels to me now a book whose time has past, and drowned in particular under the mantra of ‘growth’ as the sole name of the Redeemer. Even called ‘Sustainable Growth’ it is a lie of patriarchal capitalism, soon dropped by political parties in both government and opposition.

One of the finest metaphors of this feminisation is the highly ironic, given the association in traditional iconography with vain women and the integral (as grotesquely vain patriarchs say) vanity of women, is the use of mirrors in a piece of named The Mirror: generalising the human desire to look at ourselves, the absent mirror speaks a little of the fear of ageing and passing, but it provokes a history of mirrors in fife, this thought and to the history of Pictish stones in which mirror images are found. But you can use such ‘reflections’ to see how even the ‘Black Loch’ ‘reflects’ but also carries memories of many species drinking at it, some now extinct there (wolves and boars) and absorbing ‘diesel particulates’ that ‘fall into it’ and ‘fly-tipped polystyrene’.

Women connect past & present but that of each sex/gender important to life. This book cares about what we do when we clear the past – whether it be our parents’ bungalow on their death, or Highland Peoples in the ‘Clearances’. Yet there is so much mud and ooze that insists that nothing than can be clear in this book,like the soiled ecological networks and patterns of water and air themselves, crisscrossed by machines pumping out diesl, dredging but depositing again where a return of mud is certain. We dream in this book of repopulating the cleared areas of species but forget time is in truth irreversible whatever its seeming cyclical nature. The hard lessons are taught by stone, even the unlikely Miss Stone associated with Daisies In The Sun.

And what gets extinguished first are the vulnerable and this returns us too to the class politics, and the role of indigenous populations moved out by gentrifiers that Berger might have noticed. In 2012, she was surer of this, Kathleen Jamie. Then she said to Sarah Crown:

“People are just too put upon, downtrodden, frightened, worried [to write],” she says. “So if you eliminate a whole class, you’re going to eliminate what goes with them – working-class music, acting, literature – a citizen’s wage would enable a cultural flourishing, a human flourishing, which is being squeezed out, especially with the younger ones.”

Though her own parents were bourgeois, her father an accountant, her awareness was that it was the folk culture of the working classes whose extinction preceded the great extinctions as these people became alienated labour and slaves, for wages and their consumption, for consumer capitalism. It has taken me writing this to realise that Kathleen Jamie is a poet I must revere, though to tell truth as a speaker, except when reading, she is resistible. If you have chance to see her (the book is not out till June, do!. She is truly magnificent.

And my despair has lifted as I have become aware of its cause and found that ‘Nothing is there for tears’. The world contains poets. Kathleen Jamie is a great one. We need to listen and keep on working to mitigate, ever mitigate the depredations of patriarchy, capitalism and the monstrous ideology of growth that diminishes the only thing we need more of: continuing diversity of LIFE!

Whatever else you do, READ Cairn!

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] Sarah Crown (2012) ‘Interview: Kathleen Jamie: a life in writing: ‘When we step outside and look up, we’re not little cogs in the capitalist machine. It’s the simplest act of resistance and renewal’ in The Guardian (Fri 6 Apr 2012 22.55 BST) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2012/apr/06/kathleen-jamie-life-in-writing

[2] Patrick Barkham (2019) ‘Interview: Kathleen Jamie: ‘Nature writing has been colonised by white men’ in The Guardian online (Thu 17 Oct 2019 11.00 BST) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/oct/17/kathleen-jamie-surfacing-interview-nature-writing-colonised-by-white-men (my bolding).

[3] Jamie 2024 op.cit: 78

[4] Ibid: 98, 136

[5] Ibid: 91

[6] Ibid: 100

[7] Ibid: 97

[7] ibid 62

[9] https://isabelarmitage.com/2019/11/18/yorkshire-farmers-set-up-group-to-preserve-endangered-curlew/

[10] Ibid: 112

[11] Ibid: 106f.

[12] Ibid: 109

[13] Ibid: 48f.

[14] ibid: 64f.

[15] ibid: 15 – 17

[16] ibid: 105

[17] Ibid: 25

[18] Ibid 72f.

[19] ibid: 53

[20] ibid: 96

[21] ibid: 19 & 69 respectively

[22] ibid: 14f.

[23] ibid; 77

[24] ibid: 38 & 61 respectively.