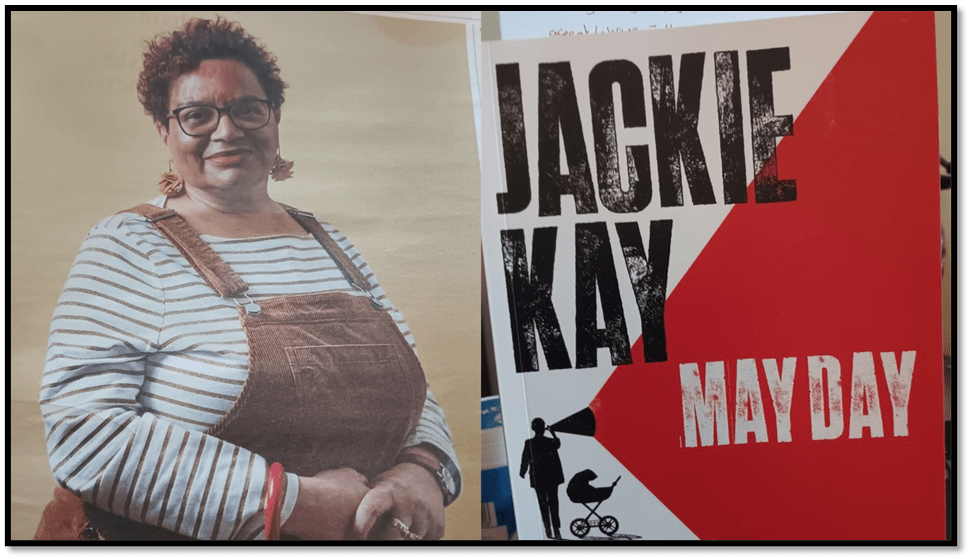

This blog is in sheer joy in having heard Jackie Kay read from her new collection, May Day, at the Hexham Literary Festival in The Queens Hall, Hexham, on 26th April 2024 at 8.15 p.m.

Infer the answer to the prompt from this blog! However, this blog started as a preparation to see Jackie Kay at Hexham but now I have seen her I feel re-directed. Of course she signed my book and I relished the reading at the event. The event was, as is becoming more common, oddly over-controlled from the stage but Jackie did not seem part of that planning, openly wondering why organisers saw fit to abandon Q & A. But as always Jackie radiated warmth, even to her host Claire Malcolm, who very much was the focus of control here. Jackie Kay I have seen read many times before, of course, to my delight. It is always a highly pleasurable experience for she is a charismatic reader of her poetry and that of others. But above all Jackie Kay shines as a person and that matters to her poetry which takes her own life and celebrates the happenstance of life events as if they were miracles. Her life is an extraordinary one however and the events have a resonance in the history of others, but not others usually celebrated in poetry: the lives of leaders of the political working class in Scotland, if not only there, for her parents Helen and Jack Kay had access to the networks of those standing against the status quo of neoliberal capitalism and state oppression, and their surprising meeting points, across many countries.

I should give up reading poetry reviews though. In The Scotsman, Stuart Kelly says that he finds ‘poetry by some stretch the most difficult form of writing to review’, insisting that he may make demands of poems that they don’t always fulfil. Unsurprisingly for Kelly, a prig at the best of times, he wonders if he sets his standards too high especially because his ‘particular preference is for work which is, in his words, ‘askance, oblique and – dread word – difficult’. The two poets, one of whom is Kay, must await sentence as he further outlines his demands. They are that a poem be not only be available to read, but that it can be re-read in oder to gain more than from the first reading. Poems should not be ‘instant hits or oysters to be gulped whole and unthinkingly’. A good poem then, for him, is subject to his expectation that its poet demand effort from the reader by demanding it of their writing, or as he puts it: ‘I expect to put as much effort into reading a poem as the author hopefully put into writing it’. And, unusually for him, Kelly does not find Kay wanting by this yardstick (for finding deficit is his usual mode) praising a poem I rather overlooked Flag Up Scotland, Jamaica and speaking of effects of language use in its first stanza as ‘so subtle as to be almost unnoticed, but the full stops carry force’. [1]

However, if Kelly never really raises negatives about Kay’s poetry in this volume, others do, using criteria somewhat like Kelly’s. Rishi Dastidar in The Guardian rather shames the poet for not working as hard to respect his intelligence about language beyond musicality and local Glasgow colour:

While her language at times could work harder to dodge cliché (a “gunmetal grey” river “stretching away under a lead sky”), Kay’s impeccable musicality is a delight, as is her Glasgow: a backdrop to hymns of secular solidarity, “a place of welcome / to the citizens of the world”.[2]

The poem he refers to is Clyde, in this stanza:

The river was gunmetal grey,

Stretching away under a lead sky.

And when the ship slipped into the Clyde,

Grown men cried.[3]

Yet does the poem really need to work hard to colour the effect it wants with technical surprises and unexpected choices of colour metaphor. ‘Gunmetal’ is precise in the context of the production of armaments, and the reflection of metal on metal prepares us for the couplet that follows that moves from looking at riverscape to imagining the launch of ships that once went on in its dockyards, linking labour to the machinery of war and transportation. In fact I think the words are chosen well (possibly the result of hard work such as Kelly requires). The rivet and nails bond forcibly together (both are implements mentioned in the first stanza) two distinct ideas, and perhaps another, for the stanza recalls the monochrome photographs known so well to the families of Glaswegian dockyard workers, of launches variously of floating gunpower or the boats that will carry Scottish emigrants to new lands (another idea that emerges through the poems handling of the docks as a ‘place of memory’) where all reflection from within the photograph outwards towards us is in variegated grey.

I think grown men still cry at such memories, though the direct holders of them are themselves now grieved themselves.

I am sure that hard work goes into this poetry (if that matters) and more so is hard work repaid if put in by the reader in increasing treasure of emotional nuance. The problem for many critics is that Jackie Kay’s poetry does have immediacy and even the feel of poetry we contacted early in our life – the lyrics and rhyme of verse for children – whilst concealing treasures for readers whose honest work might be more like that of a whole beautiful democracy of labour than the starry talk of elites. Take Rishi Dastidar again who has produced political poetry but that of the alienated and isolated dependent on the crumbs from the table of the status quo (see my blog on his Saffron Jack at this link). He says in praise of these poems:

Kay’s eighth collection weighs the loss of her parents against a celebration of collective power and the joy of protest marches, themes most successfully intertwined in the title poem: “What can I say but flame the alarm / before our world goes up in shame.” [4]

He is right. The idea of the strength of a collective force of the people is a strong theme of the poems but its relationship to personal elegy for her parents is not weighed against that theme in another pan of our metaphoric weighing scales. Far from it, for the elegy for Helen and John Kay is not to be divorced from their introduction of the young Jackie to a politics of collectivities rather than mere individual protest (Twitter-wise one might say) against injustice. For what is mourned in Helen and John is that they showed that love of each other as individuals, families, local communities of place or mutual interest or identity, nations and a collective global ‘world’ are interconnected, perhaps inseparable. This kind of socialism is not that of modernity, but its roots are still there. The whole point of Jackie Kay’s style is to invite everyone to the table – the ‘hail clanjamfrie (whole crowd of them –’ in an act of politicised humanity, under an umbrella of interests that do not divide us from each other.

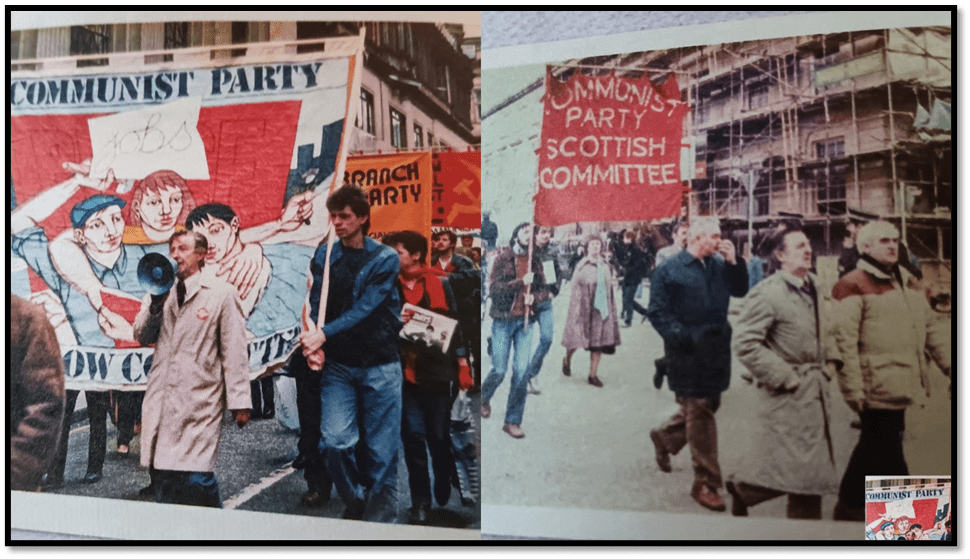

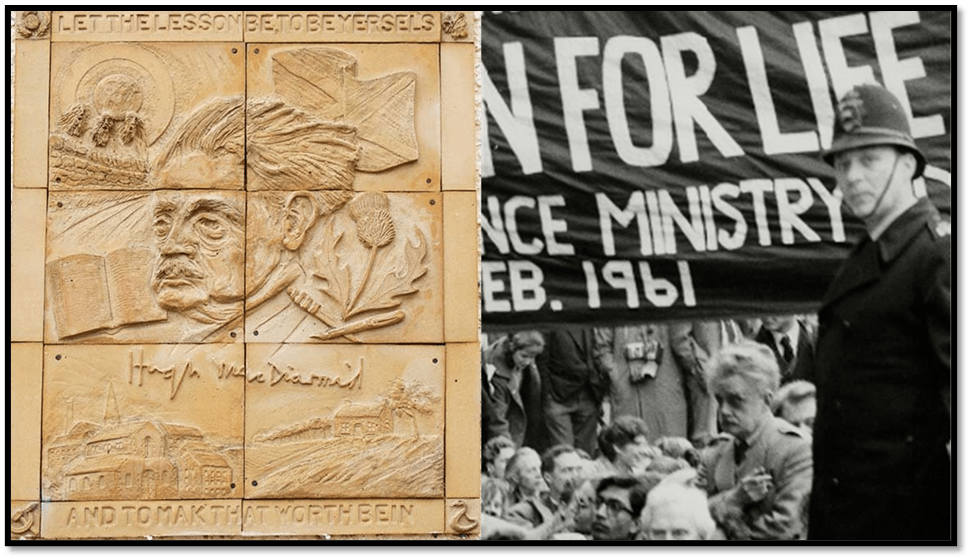

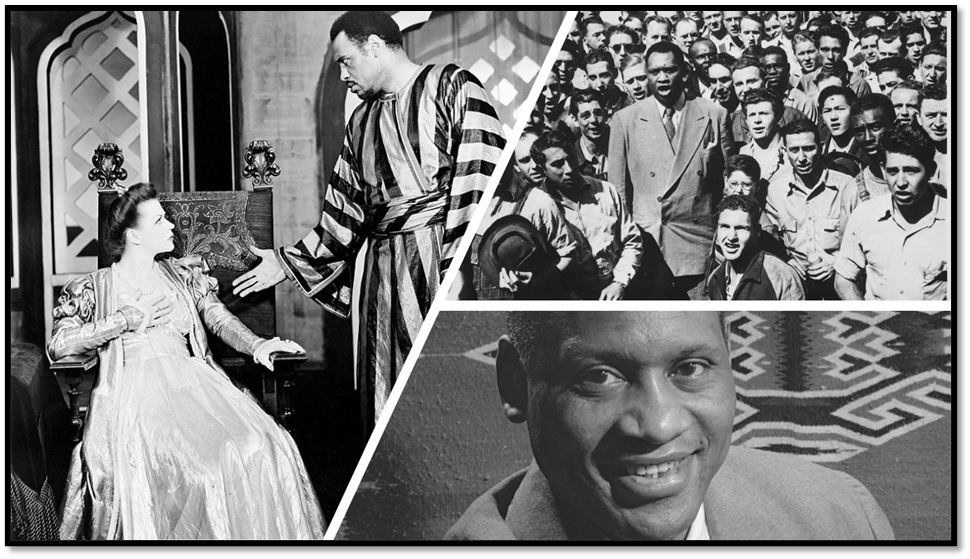

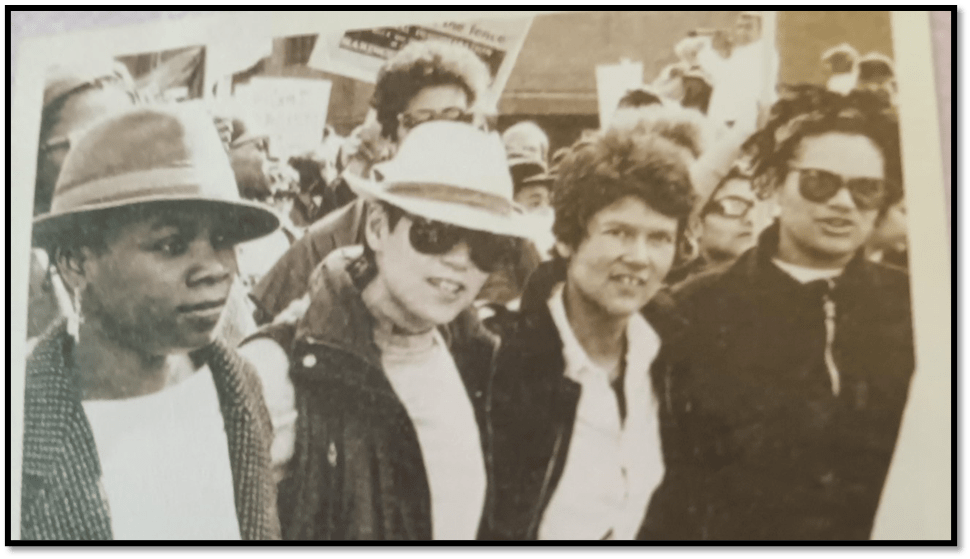

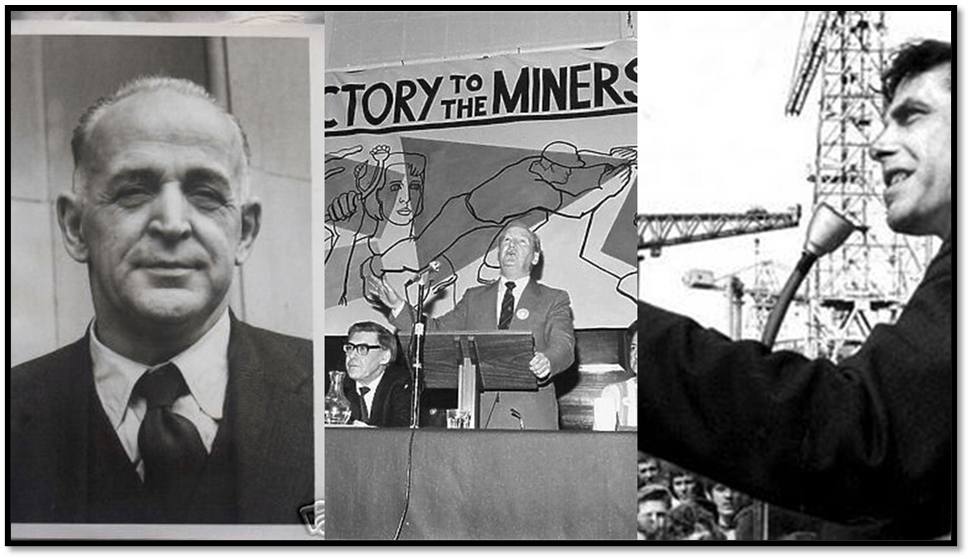

Such collectives gather together the differences in people, such that leaders and people join together in one march – and these, in the poem mean known and forgotten Socialist and union leaders, global Communist activists in numerous cause (from Rosa Parkes to Rosa Luxembourg) and allied artists and people in the provision of culture (as isolates like Peggy Seeger and perhaps Nina Simone) or in collective institutions of culture (like Harry Belafonte and, of course, Paul Robeson, for who the whole collection seems a bow of memory. And then there are the political party workers – passionate people rather than apparatchiks – including the poet Hugh MacDiarmid who pushed the pram of Jackie’s elder brother on a protest march) but also cultured people in the resistance movement to the status quo within both political parties and trade unions, like Gordon McLennan (still the Leader of the CPGB when I was in it), Jimmie Reid, Abe Moffat, and various nameless marchers in protest. Some of the names of the latter must be memorised because they died from the brutality of state weapon use whilst in peaceful protest like Nahel M. All this is to be mourned with the passing of Helen and John Kay, by being turned into collective action in order to ‘shatter this mosaic of sorrow’ against which we protest.[5]

There is no room here for precious literary elites, the last bastion even of a politics of protest entirely locked within the anomie of modernity. Jackie Kay’s first experience of poetry might have been:

My brand-new mum carrying wee me.

My brother in a pram pushed by Hugh MacDiarmid,

Black beret on, bead eyes, lined face,

But greet and in yer tears

Ye’ll droon the hale clanjamfie![6]

In this poem of her sixtieth year, the elderly face of MacDiarmid (lined like his poems) is remembered as a friend of the family ad their links to the causes of peace and equality at the same moment as one of MacDiarmid’s most wonderful poems is quoted, The Bonnie Broukit Bairn.

Hugh MacDiarmid

Mars is braw in crammasy,

Venus in a green silk goun,

The auld mune shak’s her gowden feathers,

Their starry talk’s a wheen o’ blethers,

Nane for thee a thochtie sparin’

Earth, thou bonnie broukit bairn!

– But greet, an’ in your tears ye’ll drown

The haill clanjamfrie!

It is a poem of the nature of Robbie Burns To A Louse, laughing at those who think themselves better than the rest of the clan because of their colourful get-up, and imagery (the sort Rishi sadly wants of Jackie) who never think, not as much as ‘a thochtie sparin’’, of those less provided for than is their own self-interest – in this case the bairn that is the ‘Earth’ vulnerable to war, and, in other Kay poems, to climate change and species extinction. Children learn early with the Kays not to cry in sorrow but to protest, and art works with him in equality not from high above them. That is not to say that personal sorrow is not a feature of May Day: after May Day is a Labour celebration day as well as of spring, and in whichever communal but it also a distress call from a vessel that is sinking and isolated from help, as in the poem MayDay:

Now, I’m declaring an emergency.

….

Not pan-pan, not SOS,

Not m’aidez or venez m’aidez

But MAYDAY MAYDAY MAYDAY[7]

There is more of that personal grief in the beautiful Grief as Protest, which strains to connect the isolated loss to the communal consolation in lament and elegy but sometimes fails. Stuart Kelly lauds Kay as a poet of elegy:

It is the elegies that are most impressive here. Elegy perfectly suits Kay’s skills. They must be transparent and yet lingering, they must be affecting without being mawkish or obviously sentimental. The best of these utterly cut to the quick. All I can really say is yes, that is exactly what it feels like: “I cannot / shift the feeling that someone / has been close; some unseen / has touched my hair as I nearly dreamed / as I nearly went, as I nearly fell off.” “All of that was for all of this, / and now you’re on your tod”. Sometimes there are strange synchronicities. Tod, meaning alone in Kay, meaning, as in Strachan’s concrete poem, a fox, meaning, in German, death.[8]

This is finely noticed but not a comment on any ONE of the lyrics cited as unique poems with different meanings within themselves. For instance take the one using this analogy, of ‘tod’ as both ‘death’ (in German) and ‘alone’. To my mind in reading, when Jackie Kay weeps she weeps for her parents as their now child alone but also for what they represented to herself AND others. And that latter meaning, of the communal protest at what seeks to limit humanity (which death does and must at some level, need not leave one alone for long. Elegy is a social and ritual form. At the event Jackie spoke of creating gatherings as a secular equivalent of the religious congregation or assembly. There is social ritual and joy in the kind of protest organised by either Helen or John Kay.

The joy of the latter is perhaps less in evidence in politics these days, but it is not dead. Dastidar is wrong about his weighing scales, setting personal grief and protest, against each other, precisely because of the achievement of a poem like Grief as Protest. For it, a bit like In Memoriam but with more wholesome political beliefs behind it, abandons private grief after paying its necessary dues for it is a necessary stage for Jackie, for a return to ritual mass protest metaphors and uses the many not to ‘reassemble loss’ but to limit it to the fact of mortality alone NOT oppressive human systems:

The wee beliefs still gather

On the street corner, at George Square, or under the Hielanmann’s Umbrella …

As if, in that company and in those numbers.

You might reassemble your loss for tomorrow.[9]

Hielanmann’s Umbrella is a real place in Glasgow (a glass fronted bridge – see below), where assembling protest marchers might meet but Kay is a poet of modern mass protest too and umbrellas are rife in modern political discourse, to indicate alliances (as in the LGBTQIA+ movement) or the coloured umbrellas used against police guns to emphasise peace against war (umbrellas not guns) in modern protest – or the wholly yellow ones used in Hong Kong. Grief as Protest is a better poem than In Memoriam for it holds private grief up against a genuine public standard of democratic protest not an illusion of public well-being that excludes the masses as in Tennyson.

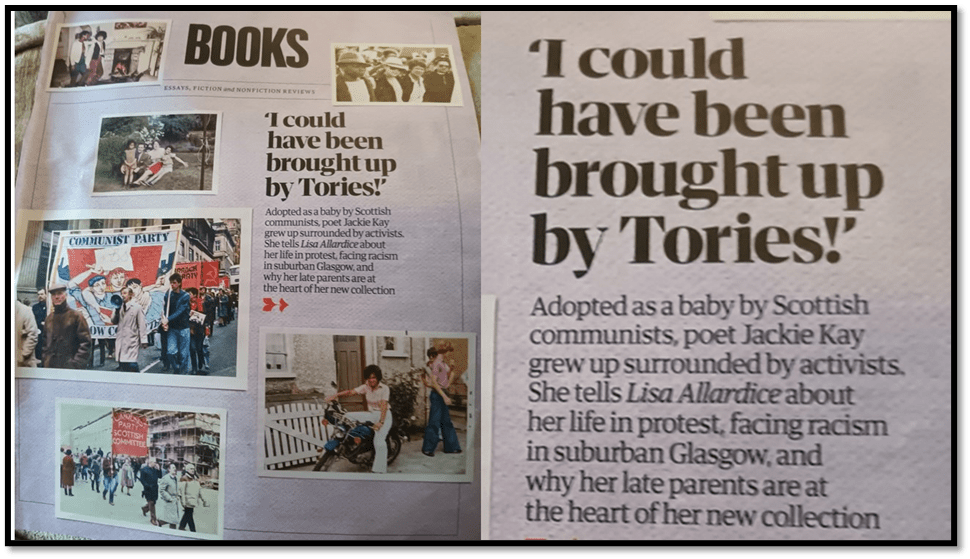

In a wonderful interview with Lisa Allardice in The Guardian, Kay’s political discourse resonates with all of these terms:

The march remains a beacon of hope for Kay – there’s still a faded Black Lives Matter poster in the window. After a period of what she calls “generation apathy”, she is thrilled to see young people politically engaged again. But she doesn’t recognise today’s culture wars in the identity politics of her own youthful engagement in the late 70s and 80s. “This is the age of polarisation. This is the age of division and splits. This is the age of judgment. This is the age of shame,” she says, with the rhetorical flourish of one brought up at the barricades. “I really long for the times when we had genuine debates and people could really disagree, but still be friends.” She sees our current anxiety about language and definitions of race and gender as a reflection of a deeper cultural unease: “When you can’t choose the words comfortably, that shows what else is going on,” she says. “I’d like to get back to umbrella terms, because there’s more space for people not to get wet.”[10]

Her feelings about union of interests (‘umbrellas terms’ in short), what has passed and what remains in radical politics and suspicion of the over-boundaried individual or binary us and them (male and female too) sectional interests all speak out in this passage. Some individuals encompass masses, and often in complex intersectional ways, as in those outstanding poems in the book about Robbie Burns and race, written to celebrate a coming together of discourse about Burns in an entirely un-antagonistic way in a special exhibition at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery:

Douglas Gordon’s Black Burns at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. Photograph: Jessie Maucor/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017, courtesy Studio lost but found, Berlin and Gagosian

The same could be said of Robeson and Belafonte, and, also, of John Kay, Glasgow secretary of the Communist Party and Helen Kay as Scottish secretary of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. The key poem celebrating them and what was passed on to Jackie and then to her own son Matthew is sung in the poem meant to be the key one of the book. Allardice says:

The poem A Life in Protest (the working title of the collection, rejected as “too screechy”) charts 60 years of activism, from the time Kay was a babe in arms – “My brand-new mum carrying wee me” – at the demonstrations against Polaris missiles in Holy Loch in 1961 to the Black Lives Matter marches just a few years ago. She talks proudly of the “Remain” badge her mother wore on her red dressing gown, even when she was housebound. Her dad was such a devoted Guardian reader that Kay put a copy of the paper and a thesaurus in his coffin. “I hadn’t read it yet!” her mum scolded her a few days after the funeral.

The blend of personal and political, of individual, group and mass-political is superb here. I wonder if I still don’t prefer A Life in Protest as a title for the whole volume given the ways that the right have commandeered the idea of May Day and returned it to pre-Christian celebration and Christian versions thereof. It brings under one umbrella the Kays’ joint marches from the past with Jackie’s attendance at LGBTQI+ Pride, Redeem the Night, and Greenham Common feminist marches. It unites these with the list of names of those with a lot to lose for going on those marches, which carry through to other poems also. Paul Robeson in particular with his associations to rivers (the Clyde being co-opted) that ‘Keeps rolling, he just keeps rolling’.[11]

Jackie as a woman on marches amongst her young peers is with us in these poems.

However, Jackie is also there as the mother of Matthew Kay, (M.K.). She knows the nicknames of his flatmates and knows that their support for umbrella terms causes as ‘trans-affirming bros’, ‘queer-affirming’ and ‘loving diversity’ as well as Black Lives Matter.[12] The idea of chosen association and connection through and by keeping distance are so beautifully spoken and nuanced in these poems they should be compulsory reading for parents who cling. But Banquet for the Boys is a great poem because it celebrates associations, friendships and remembers forgotten names or names only known in certain circles. That makes for some great lists of forgotten socialist activists in some poems that have real rhythm as you read over them. But don’t JUST read over them. Look them up:

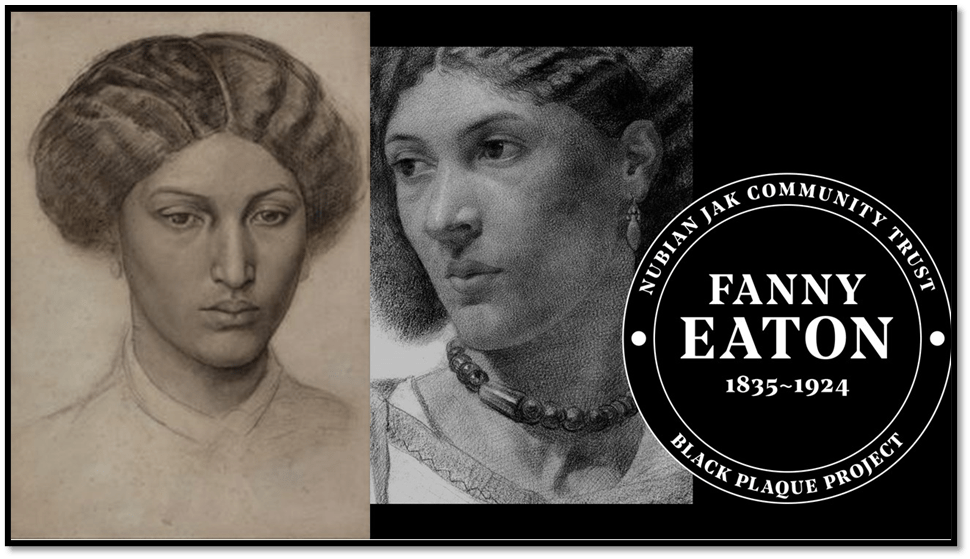

Home or hame are important cognate concepts in these poems and family matters, but it is wider than we think, even when these words aren’t used – in the wonderful poem on Fanny Eaton as a woman who lives ‘here’, whether we notice her or not, the fate of black people and black women in particular even when feted by Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhoods.

I wonder if Kelly and Dastidar like Kay’s rhymes. My favourite is that used to describe what the harbour of the Clyde ‘holds’:

The harbour porpoise,

The sense of purpose,

The dawning of a new day.[13]

Lewis Carroll played with near homophone ‘purpose / porpoise’ but not with the political purpose of Kay trying to make May Day a ‘new day’. Kay believes in political purpose. It bridges the isolated life of working artists with a communalism of shared belief. Now a feature of Salford University, Kay has celebrated the holdings of he artist Albert Adams, held in quantity in Salford’s archives.

But this is no jobsworth work for her as her podcast on the university site shows. Adams matters she thinks because he thinks like a poet, linking past suffering to present protest and future liberatory purpose.

And what I love in these poems are the games she plays with words like ‘drew’ that can be political as in the following, where the ‘lines’ created on Adam’s oppressed face match those etched in his drawings, especially the 1956 Self-Portrait, the lines drawn between people and peoples by apartheid and the lines of a poem. This is meta-critical heaven, subtler it seems than the full stops Kelly notices elsewhere:

The lines of South Africa

Etched on your face – whey drew

A line at you, whey crossed a line.

How you drew and drew and drew

Resistance in the lines of protest.

Since not ‘screechy’ at all, I would have called this book ‘lines of protest’. But even more beautiful meta-critical reference comes with the play in this book, full of complaint about the ecological damage of modern wasteful capitalism and inequality, on the word ‘air’. It is an important word in poetry, especially for a Burns lover, for he kept the seventeenth century meanings of it as a musical song alive a long time. They are anyway a strongly Scottish verse tradition honoured by MacDiarmid too. I will give one example from the opening of the varied trilogically structured poem Farewell 2020 about COVID and the link of epidemics to the loss of a safe natural environment, as well as the fact that air quality improved during lockdown.. See how we move from air to breathe, to the air breathed out (perhaps by someone sick) to air to sing or chant.

This air has heather and malt on its breath

As it sighs, puffed out after a year of death,

…

And this air has been no able to sing

The old familiar airs, or fitba chants, or hymns;

Or blend its griefs in masses for the dead;

…[14]

And there, by the way is another excellent title in a poem that links ritual singing in football chants with those in funerals or folksongs and all without a mention of the political folklore airs of Peggy Seeger, that comes elsewhere, for she too befriended the Kay family.

The thing is that , like Lemn Sissay, who revealed to her in public that he once hated her for the rarity of a successful and beautiful adoption parentage unlike his own, and that of countless others (Jenni Fagan for instance). I too sometimes wish she wasn’t so happy in recognising the dark side of our world, its politics and their reflex on individual lives. Unlike mine, her politics are a long way from austere. She sees politics as a great party and as a result she is likely to invite more ‘joiny inners’ (her term) to join the party and the protest than I ever would do -although not so Lemn Sissay I think, another party animal now (see my blog at this link). The well-known artists and the less well-known political activists join in with them all in an ‘air’. It is quite seriously beautiful.

Where great John Maclean came home from the Clyde,

Paul, with his compaňeros side by side.

Shoulder to shoulder with the miners, weavers,

the joiny inners, ghosts of comrades in the May air.[15]

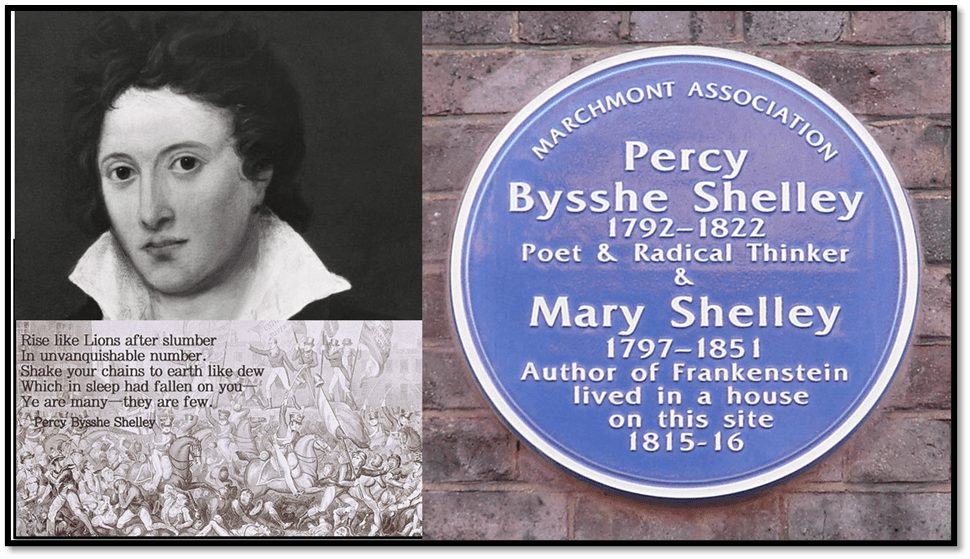

But look at the photograph above and by all means read this volume as a celebration of the ongoing generations of a fine family, where the biological and chosen are a forgotten binary as they should be, but see it too as a tremendous boost for a new politics that links to older popular traditions that are not even intended to be recalled by Old or New Labour Parties. Those latter are still the possession of the few, a stepping stone only to the dream of Shelley:

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Stuart Kelly (2024) ‘Book reviews: Dwams by Shane Strachan and May Day by Jackie Kay’ in The Scotsman (no precise date) Available at: https://www.msn.com/en-gb/news/other/book-reviews-dwams-by-shane-strachan-and-may-day-by-jackie-kay/ar-BB1lIVU5

[2] Rishi Dastidar (2024) ‘The best recent poetry – review roundup’ in The Guardian (Fri 5 Apr 2024 12.00 BST) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/apr/05/the-best-recent-poetry-review-roundup

[3] Jackie Kay (2024: 8) May Day London, Picador Poetry.

[4] Dastidar op. cit.

[5] Ibid: 30 (from The Pablo Picasso Estate)

[6] Available at: https://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/poem/bonnie-broukit-bairn/

[7] Kay op.cit: 59

[8] Stuart Kelly op.cit.

[9] Kay op.cit: 67.

[10] Lisa Allardice (2024) ‘Interview: Poet Jackie Kay: ‘I could have been brought up by Tories!’ in The Guardian (Sat 13 Apr 2024 09.00 BST) 43ff. Available online too: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/apr/13/poet-jackie-kay-i-could-have-been-brought-up-by-tories

[11] Kay op.cit: 7

[12] Ibid: 65 (in A Banquet for the Boys)

[13] Ibid: 9

[14] Ibid: 12

[15] Ibid: 24 (from When Paul Robeson Came Back to Glasgow)