Describe a decision you made in the past that helped you learn or grow.

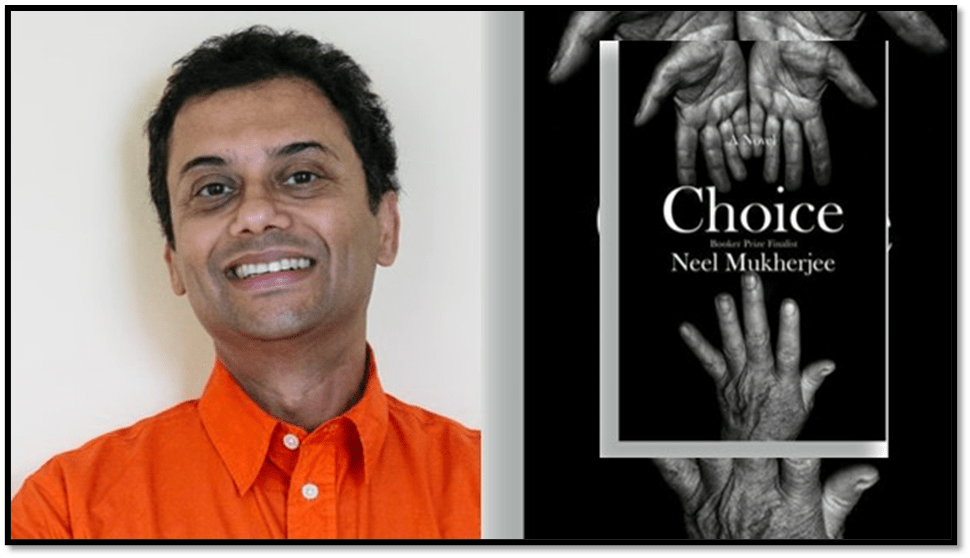

Neel Mukherjee’s opening story in his novel ‘Choice’ has helped me realise that, if to develop as people is to value the uncertain ethics of all decisions and choices, it must be our decision not to become a gay male couple pioneering adoptive parenthood & that this helped us grow together.

First, I want to make a plea that you don’t misunderstand my title statement, for my husband Geoff and me have been together a long time, had and have a lot of love to share in a chosen family had we chosen one. We would, I think, have made good parents dedicated to any children who we chose and who chose to stay known as our extended family through their adulthood. The decision not to adopt was long in the making, with many reversals and turns in it, but was eventually not to do so. I will summarise my personal thoughts on this at the end of the body of this blog, which is of necessity a blog about Neel Mukerjhee’s novel Choice. This is because this novel has prompted me to think about the issues again in a way I found disturbing, as only rather complex, great, and nuanced art can do.

Choice is a novel about the scope for making all kinds of choices and decisions that are and remain ethically defensible and yet Neel Mukherjee decides to focus in one part of his first story on the strategic and ethical meanings that influence two queer male parents to choose to parent children and implicitly to prioritise their children’s needs over other issues in their relationship. I found the treatment of this topic uncomfortable and felt I needed to explore why. This blog then, though at the end being about why Geoff and I made our decision as it was, relates to Neel Mukherjee (2024) Choice London, Atlantic Books, and must range wider than that issue.

However, this is not a review of Mukherjee’s novel Choice, which has seemed to puzzle and trouble the critics of it I read in very different ways. Instead, I aim in this blog just to look at the first story in the collection which charts a crucial moment in the breakdown of a queer male relationship. The story has a primary relationship to other stories in the novel: the second being a manuscript of a story in a collection of stories assessed for publication by one of those men, Ayush, who is a publishing editor responsible mainly but not only for commissioning stories that speak from the perspective of cultural diversity. The third is a story related to a conversation Ayush holds with a colleague of his partner, Luke (like Luke an academic economist) about means of addressing poverty in rural Indian Hindu communities by providing livestock that must be cared for (a cow and therefore not available to the Hindu couple as meat). But those contingent links between the stories do not make for clear deeper links that render their relationship in the first story any more intelligible, especially its cruel resolution in relation to the disposition of the fate of an elderly pet dog owned by the coup, Spencer.

The decentring in this story is replicated within the first one in particular b radical shifts in the consciousness through which the story gets told and we might suspect therefore that the fragmentation of a point of view of the world is important in Choice. It opens for instance with Ayush watching a film, of which more later with his children, ‘their eyes unblinking’. He ‘caanot know’, we are told (as a reflex of Ayush’s own consciousness, ‘if what they are seeing through their eyes is the same as that which he is witnessing through his’.[1] We will return to the shifts in perspectives between differing eyes in this novel. It is important in relation to its ethical take on issues and its art – indeed they may be one and the same thing by virtue of this motif.

Varied perspective is manifest, for instance, in the problem of finding coherence between a number of different stories in a single unit, whether labelled merely a collection of stories or narrative master framework (such as Choice may be). This idea is the focus of a meta-discussion about connecting up the themes of stories between Ayush and the author he is currently working with, the reclusive and secretive, M.N. Opie, about whom we learn little more than this name. Abhrajyoti Chakraborty in The Observer thinks this important, citing this exchange as summarised by Chakraborty:

Opie wonders if the common reader really cares about the order of the stories in the manuscript: “Can one leave the different strands that constitute a story or a novel seemingly unknit and hope – trust– readers to bring them together into meaning?” Ayush would rather the subtext was clearly spelt out. “Why not knit them for the reader?” He types, but then deletes the question.[2]

Yet the critics are agreed on the focal importance of ethical and moral decision-making in this book. Tanjil Rashid sees the book, prompted he says by a statement of Mukerjhee’s, as a verbal and written version of a medieval triptych:

In the middle ages, morality would be transmitted in images. Churchgoers would commonly find above the altar a panel of three paintings relating a biblical parable or commandment. Such altarpieces could be found in Buddhist shrines, too, which might be adorned with three scenes from the path of enlightenment. … / Choice has been termed a triptych by its author and, like its visual forebears, the novel needles our moral impulses. The issues in question, from climate change to global poverty, are modern, but the novel’s interest in sin and virtue is redolent of the triptych’s medieval preoccupations. /…/ …At home with neoliberal Luke and at the offices of his multinational, Ayush encounters an outlook defined by “the centrality of money, its foundationalness”, which crushes the humane values he reveres as a scholar and publisher. Ayush’s interior monologue is compelling, especially the satirical vignettes from a publishing industry mired in “white mediocrity”./ But there’s no straightforward side-taking in Choice. ...[3]

This is all true of the book I think both as a characterisation of the obscured ethical intent of the first story and its ethical dubiety. Johnathan Lee, no poor novelist himself, in The New York Times, feels Choice is as much about whether there is any foundation in human beings for choice or independent decision-making:

Neel Mukherjee’s “Choice” is a novel full of characters deciding how much truth to tell. As in “The Lives of Others,” the author’s 2014 Booker Prize-shortlisted novel, we are confronted with subtle, powerful narratives within narratives exploring the gap between wealth and poverty, myopia and activism, fact and fiction. But here these themes deepen into an exploration of free will.[4]

I wonder though how such exploration can yield, as Lee later insists it does, something ‘uplifting’ out of this novel. For me it is a novel that traps you in its dilemmas, mainly about the agency of time in individual lives (animal or human), out of which there can be no uplift other than stoicism and a degree of hope. And, of course, I need to return by the end to the treatment of queer male adoption, with which I started.

However, at this point, I think I need to say something about Spencer. He is one of the two main animal consciousnesses whose view of events are involved in these stories – the other is a cow called Gauri in the third story but the consciousness of other animals – ones dying or in extreme pain included – are also invoked. Mukherjee is a very allusive novelist to be sure but one allusion that concerns Spencer not only intrigued but blind-sided me in my noticing of it, as if I had caught out the author in his use of influence only to be shown he was doing this entirely consciously.

Whilst on a trip to Epping forest, Ayush, Luke, the two adopted children Masha and Sasha, and Spencer of course, Ayush begins to intuit Spencer’s thinking from past observed experience, particularly in relation to the ‘protective stance’ Spencer has with regard to the children. However, two paragraphs later the entire point of view of the novel becomes to be seen through the consciousness of Spencer alone, for whom ‘The world is a whole map of smells’. Spencer names humans ‘Uprights’ and discerns that Luke is the ‘leader of his pack’.[5] When I read that I thought of that section in Part 6, Chapter 12 of Anna Karenina (a novel mentioned in the story) when the story is momentarily seen from the dog Laska’s, consciousness, rather than the novel’s hero-of-sorts, Levin, who is following on after her.

Running into the marsh among the familiar scents of roots, marsh plants, and slime, and the extraneous smell of horse dung, Laska detected at once a smell that pervaded the whole marsh, the scent of that strong-smelling bird that always excited her more than any other. Here and there among the moss and marsh plants this scent was very strong, but it was impossible to determine in which direction it grew stronger or fainter. To find the direction, she had to go farther away from the wind. Not feeling the motion of her legs, Laska bounded with a stiff gallop, so that at each bound she could stop short, to the right, away from the wind that blew from the east before sunrise, and turned facing the wind. Sniffing in the air with dilated nostrils, she felt at once that not their tracks only but they themselves were here before her, and not one, but many. Laska slackened her speed. They were here, but where precisely she could not yet determine. To find the very spot, she began to make a circle, when suddenly her master’s voice drew her off. “Laska! here?” he asked, pointing her to a different direction. She stopped, asking him if she had better not go on doing as she had begun. But he repeated his command in an angry voice, pointing to a spot covered with water, where there could not be anything. She obeyed him, pretending she was looking, so as to please him, went round it, and went back to her former position, and was at once aware of the scent again. Now when he was not hindering her, she knew what to do, and without looking at what was under her feet, and to her vexation stumbling over a high stump into the water, but righting herself with her strong, supple legs, she began making the circle which was to make all clear to her. The scent of them reached her, stronger and stronger, and more and more defined, and all at once it became perfectly clear to her that one of them was here, behind this tuft of reeds, five paces in front of her; she stopped, and her whole body was still and rigid. On her short legs she could see nothing in front of her, but by the scent she knew it was sitting not more than five paces off. She stood still, feeling more and more conscious of it, and enjoying it in anticipation. Her tail was stretched straight and tense, and only wagging at the extreme end. Her mouth was slightly open, her ears raised. One ear had been turned wrong side out as she ran up, and she breathed heavily but warily, and still more warily looked round, but more with her eyes than her head, to her master. He was coming along with the face she knew so well, though the eyes were always terrible to her.[6]

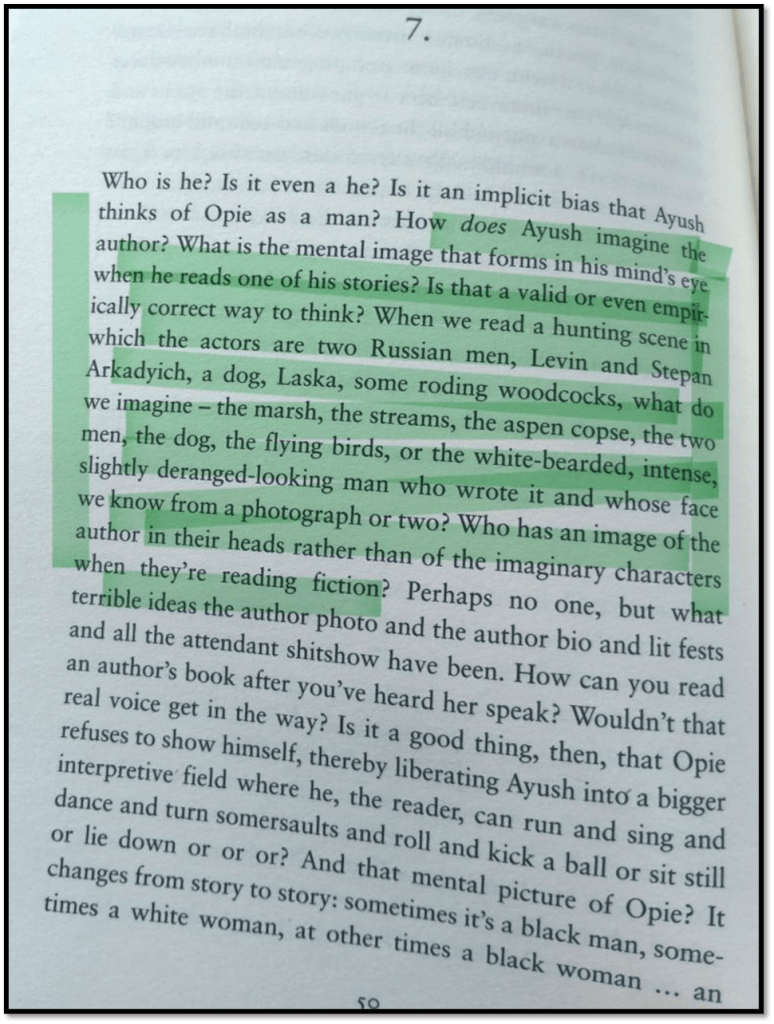

There is a payoff of vanity, in which I have no pride, from sharing a moment like this with a novelist, until, that is, in the very next chapter and page of his novel he undercuts any reader already in the know, that is, by using as an example of how we imagine an author behind their text (for him this is M.N. Opie, using a piece of Anna Karenina as a way into the mind of Tolstoy. It serves in the novel too to make us conscious of the continual de-centering of Ayush’s point of view in the story and of the author, Mukerjhee, despite the constant use of avatars (once Booker long-listed and rather frustrated authors in this and the second story) occur, particularly given that the victim of the story will turn out precisely to be Spencer.

Photograph of page 50

It is a spoiler, I know, but Mukherjee goes to such lengths, I believe, to establish the literary parentage of Spencer to show or indicate the significance of Spencer’s fate. Once Ayush has established his own lack of ethical freedom to make rational choices, he makes an entirely irrational one in its place, to write himself out of the story leaving Spencer as an illustration of the vanity of belief in the virtue of making choices in the light of the dominion of time and a necessary ending. Where does he go to?: ‘outside time’ is all we are told.

Spencer is in dreadful pain from irreversible arthritis. He will, in a short time, die. The children and Luke mourn him, ready to learn how to face mortality in lives by learning from Spencer. Luke is practical like that. We know he will ease the pain of Sasha and Masha, as a good father must learn to do. Not so, yr. He must show Spenser that even in the pain and isolation that must lead to his death,he must make a choice, though the outcome of that choice would be just a more immediate death than seems to lie in wait otherwise. He places Spencer in the middle of a busy dual carriageway road and leaves him there, going himself we know not whence ‘outside time’ though probably not back to partner Luke and his children.

The end of the story involves the abandonment of Spencer to an impossible choice; a limitation to a binary choice involving a disaster, which ever option taken, for Spencer, ending as he must as ‘roadkill’. Nevertheless, Spencer is left with a choice, though a dire one. It is as if Ayush insists on illustrating to us that no being has choice in a world in which you hold no control, like Spencer’s world now, for he can now barely stand and walk and hence doesn’t want to move’ from his ‘cage’ of pain:

Ayush lifts the substantial weight that is Spencer, judges a gap in the traffic, runs across to the median metal strip, and deposits Spencer on that border – whatever way he chooses to cross, his low, arthritic body will be in the full flow of fast-moving traffic. [7]

What Spencer is forced to realise by Ayush, having shown a preference for family life with children, is that you have no control even having chosen that life, for there are no real choices. This is the crux of Ayush’s differences to husband Luke. The latter believes that free choice determines markets, which, in turn, determine lives. Ayush is so sure of the idiocy and damage caused by market forces that he believes that he could never make a choice that would not have bad consequences on someone. He even wants his young children to be aware of this by showing them without preparation and support for their sensitivities, an animal activist film about the cruelty involved in the slaughter of pigs for and by the market for pork.

Of course, as Lee says, it goes deeper than beliefs about choices for Ayush. Many times we are reminded that Ayush fears choice and submits to the ‘only way’ that he thinks things can happen, either that or he acts surreptitiously in gifting the children’s education nest-egg to climate warriors. Even when Luke seeks to comfort Ayush Ayush feels conflicted, unable to decide to accept his husband’s comfort and the conditions of agreement that he fears come with it< Hence: ‘The only way Ayush can stop Luke going on is to lean into him and let himself be enfolded’. [8} I italicise ‘the only way’ here for the phrase characterises Ayush’s sense that he ought to be ‘kicking against the pricks’ but isn’t. he just lets others, like the children he must get ‘ready for school’ determine his life and the use of HIS time for: ‘Nothing is straight forward, least of all time’. He is (and not the beautiful pun on ‘settling’ in relation to war, quarrelling, or finding a home to live in):

…. at war with wherever or in whatever he finds himself, never settling, or settling down, with what is given. Shouldn’t existence be a quarrel with all that could be better but isn’t? but what does it mean to not belong to your own side, … For him, it’s the only way to be and the costs as Lukey would put it, are enormous. [9]

If for Ayush, there is a rule demanding he follow the ‘only way’, one without alternatives, he can see to act, then this inevitably returns to him when he retrospectively revisits the decision he made with Luke, but more Luke’s than his, to choose to have children and choose to prioritise their care and support. Why did Luke insist on children, he thinks – even if it were not for continuity after death, it might be to give a meaning to their relation – Ayush and Luke- together after ‘the end of their consuming romantic and sexual attachment’love and desire ran out’. Even, as a chosen family, Ayush worries that this is adults ‘performing this big experiment on the children’ in a world wherein the children have ‘no choice in the matter. We cannot imagine what damage it might do them’. Unable to properly talk about this Ayush even sees a conspiracy in Luke’s collusion with a world that remains basically heteronormative and racist:

Had Luke planned the whole children thing so that he would have something to hide behind, an excuse, a reason, an armour, all of those together, when love and desire ran out, like they always did? How heterosexual of him, if he had. Or maybe, putting into practice what he knew from his theories of changing preferences, reference points, multiple selves, or whatever they were calling it nowadays and declaring it a great breakthrough in understanding, he had obtained a kind of insurance for one possible, perhaps only, route the future could flow.[10]

This section of the novel touched a nerve for me, for essentially Ayush argues that it is perhaps not ethical for queer people to parent children and that might be still so whilst they still love each other. This is not because they cannot enact the role of a good enough parent but because, when they do, they ape the selfish strategies that he believes heterosexual couples use to overcome the ravages of time, ageing and death, on themselves and to insert a future for themselves in the continuum of time. And suddenly why there are so many clocks, watches, schedules and statistical countdowns in this novel about possible extinctions of species and time becomes clear.

That there us a selfishness in having children is not unknown in ethical thinking. For heterosexual and queer people, there are still choices to make around the use of safely unreproductive or no sex, choosing how much time, or money for paid alternatives, to devote to childcare and support. Parents sometimes know that their children may be brought up to suffer and may blame their birthing, as Adam in Milton’s Paradise Lost, blames God for making him, snd likewise Frankenstein’s monster blames Frankenstein. Ayush has a point that queer parents bequeath even before their death the experience of marginalisation, oppression, victimisation, or lying that is necessitated in homophobic heteronormativity. We see Masha and Sasha experience this in tne novel in crude ways from other children, in subtle ways from institutions, like educational ones and publishers, whilst proclaiming that they value diversity.

I have to say that, all those years ago, in the 1970s and 1980s, this is where Geoff and I were, proud to be gay and proud to be a couple but aware of the dark fringes of threat that went with barely hidden homophobia in all areas, even the Labour Party in which we were involved, a homophobia that considerably delayed Tony Blair’s acceptance of support for further law reform around partnerships and extended educational initiatives in school. We felt unable to subject a child to that oppression in their own schooling, rightly or wrongly, since both of us had experienced it in our own schools, though we had passed as straight then.

And our resistance was I suppose also based on the knowledge that familial descent and continuity is often a choice children who must bear it into future generations must also bear without having consented to do so. Now, when Geoff is 83 (today as it happens – happy birthday darling 🎂) – and I am approaching 70, it is impossible to reverse time to take a chance at that means of personal survival in the memory of future generations and our only chance of a future at all, as Ayush puts it, without quitting the domain of time and narrative altogether, I cannot regret our decisions and choices.

Perhaps I don’t because, though our relationship has undergone tribulation and changed, it has survived all the necessary metamorphoses and is strong. When Death comes for me (I cannot think about that in Geoff), it is possible I will think of my available choices then as Spencer does not having the luxury of just dropping painlessly of the story as Ayush has because he is only a character in a novel.

But leaving children to mourn, regret their long absence from my presence, or just feel guilt at being unburdened of elder care calls and my old guy type bad temper does not solve any existential crisis for me. We bear what we gifted the world if anything and rarely know if it was anything or nothing or worse that was ‘gifted’ or deposited. I think what we have is a sense of being that can bear its own termination and does not lean towards the desire for immortality of any kind. For this all the characters in the whole novel yearn for. Chakraborty takes Mukherjee for task because, as they say:

Choice is undone by its third section – about an indigent family in a border hamlet in West Bengal. … The story is set sometime in the past decade, but Mukherjee reproduces stereotypes of rural poverty – children filling up their bellies with starch water, and learning the alphabet by scrawling letters on the ground with a stick – dating back to colonial-era Bengal. … They never seem to have any idle thoughts; even their laughter is a means to dispel “the cloud of anxiety that is the future”. Sabita keeps losing her temper – at her children, her neighbours, the cow. The kids, too, are no more than their timid, compliant selves. For the first time in the novel, nuance is eschewed for a preachy, threadbare morality. …. Does Mukherjee really think the poor, and those living in the global south, have no inner lives to speak of? [11]

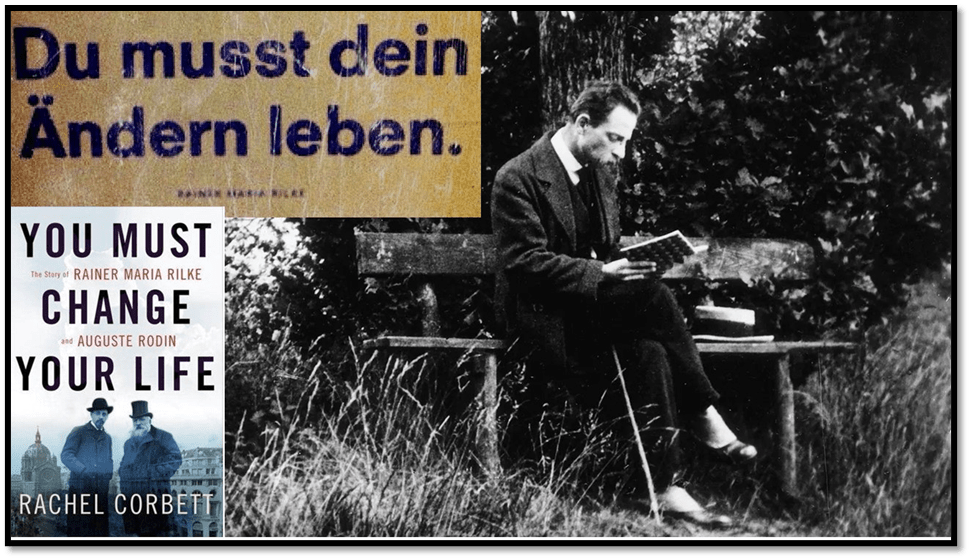

I disagree. This family does not display its its inner life as do Emily and Ayush, both acclimatised over-educated Western academics rather than merely educated persons, with a surplus of guilt about the way of the world and continually requoting Rodin’s advice to Rilke, according to Rilke, that ‘You must change your LIfe’. [12] They can not afford to display inner lives or even spend time nurturing them, so insistently demanding are the lower bands of Maslow’s hierarchy. In a sense, the cow that comes into their lives is the inner life they must sacrifice, to the meat .market in the Muslim area over the river.

Even the quotation from Mukherjee that Chakraborty gives is an index that their lives are hoist on a petard of a similar existential.nature, if physically a much harder one. In dispelling “the cloud of anxiety that is their future”, they tread the same boards as Ayush and Emily in earlier stories, and in so doing try to find how best to use and not waste time and what it gives to us now, let alone which it deceptively promises later.

So there we go, my blog is finished. I may have indicated rather covertly how I think both Geoff and I grew from the decision not to adopt. It was a challenge to find meaning otherwise. In the end, I believe that even people with children have to do that, or face instead making both their own and their children’s lives a continuum of anxiety and moral burden, possibly in relieved exhaustion from guilt at feeling release from burden at the end.

With love

Steven xxxxxx

[1] Neel Mukherjee (2024: 4) Choice London, Atlantic Books

[2] Abhrajyoti Chakraborty ‘Choice by Neel Mukherjee review – twisty tales of morals’ in The Observer online (Mon 22 Apr 2024 09.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/apr/22/choice-by-neel-mukherjee-review-twisty-tales-of-morals

[3] Tanjil Rashid (2024) ‘Choice by Neel Mukherjee review – parables for our times’ in The Guardian online (Thu 28 Mar 2024 07.30 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/mar/28/choice-by-neel-mukherjee-review-parables-for-our-times

[4] Jonathan Lee (2024) ‘In This Heartbreaker, Hard Choices Come With Hidden Costs’ in The New York Times (April 2, 2024) Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/02/books/review/choice-neel-mukherjee.html

[5] Mukherjee op.cit: 47- 49.

[6] Leo Tolstoy Anna Karenina Part 6, Chapter 12. Available at: https://www.owleyes.org/text/anna-karenina/read/part-six-chapter-12#root-16

[7] Mukherjee op.cit: 113

[8] ibid: 29

[9] ibid: 32

[10] ibid: 106 – 110

[11] Abhrajyoti Chakraborty ‘op.cit.

[12] This phrase is in all the stories with versions too like the publisher’s advice: ‘Revise and Resubmit’. For example Mukherjee op,cit: 23f., 34, 113