What makes you nervous? This a daily prompt blog that I am basing on visiting what would once have been classed as a vampiric B-movie, Abigail.

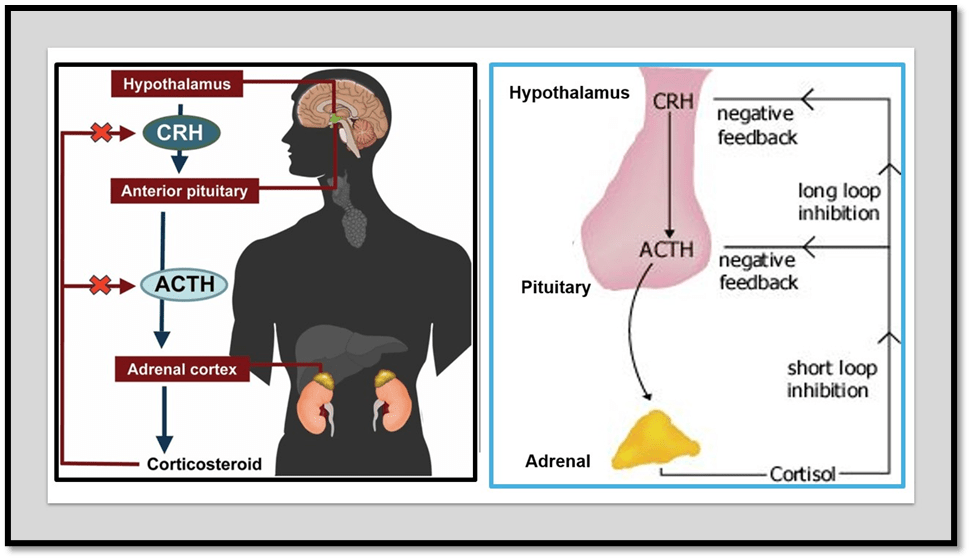

What does it mean to be nervous? Wikipedia defines the most usual form as another name for anxiety. We use it far too widely – no doubt of it – but one distinction we perhaps ought to make is between ‘nervous’ and being afraid. Fear eats the soul as they say. When we are afraid the alternative strategies of freeze, fight or flight are alone all that is left to us – every response one might make is consumed by the threat to oneself, of being under danger of some kind of damage or perhaps even extinction. The soul is consumed alive because all that is left to motivate us are the basic and unconscious motives of the Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA) axis. Fight, freeze or flight is in a sense all there is of us in fear. There is nothing left to make a person let alone a soul. Even the hopeful negative loops in the HPA charts below stop working in trauma – deep trauma.

Of course ‘being nervous’ or ‘feeling nervous’ (which must translate into an imagined feeling that one is sensing the operation of your nervous system directly as if its operations carried sensations themselves rather than stimulating them in other biological systems). Yes! The hypothalamus is probably receiving alerts when we say we feel nervous, but we are also translating the messages that are the content of those alerts in various ways. After all, the process of an excited hopeful nervousness biologically is exactly the same as one of fear and even of that of sexual stimulation. The ‘higher’ brain systems can calm those contents so the alert may stop, interpret them as unreal and unthreatening (or unhopeful), or as neither (or either) of these things. It can interpret them away sometimes unless, of course, they are tied to other deeper associations, even to some initial and buried trauma (even childhood trauma).

In these cases there is extreme danger for the person feeling fear, a kind of locked-in feeling difficult for messages from the outside world to penetrate, once the often still buried trauma (whose content is insufficiently known and appraised by the person who once experienced it as something to defend against). Child abuse in particular is difficult in this regard, for the terrors returned to were ones where the body and psyche (aspects I believe anyway of the same thing) both were far too undefended for the onslaught of the traumatic event at the time of happened.

But we all get ‘nerves’. In many ways, we often deliberately stimulate the effects of it, even unto fear. Aristotle felt tragic drama stimulated it, but that it was nevertheless a good thing because we underwent catharsis. A few words from the Wikipedia definition help here:

Catharsis is from the Ancient Greek word κάθαρσις, katharsis, meaning “purification” or “cleansing”.

It is most commonly used today to refer to the purification and purgation of thoughts and emotions by way of expressing them. The desired result is an emotional state of renewal and restoration.

In dramaturgy, the term usually refers to arousing negative emotion in an audience, which then expels it, making them feel happier.[1]

Aristotle in more detail argued (in his Poetics) that tragic drama evoked the emotions a real event of the same nature of the contents of the tragedy (including death, loss, mutilation of body and soul) but being an artificial representation of that real thing could be manipulated to relieve and/or expel those emotions. This manipulation is done by dramatists, actors and directors and the religious rituals of Greek theatre. All of these near rituals purify the body whilst exposing it to a horror that might be handled better when it really occurs in life and not just in the theatre. Some people argue that watching horror films has the same effect, although others imagine that we become so hardened to, and rewarded by, the extremes of terror therein that we lack capacity to react to real terrible events in the world or even permit us to mimic their violence (witness the ideas in social cognitive theories from Albert Bandura onwards).

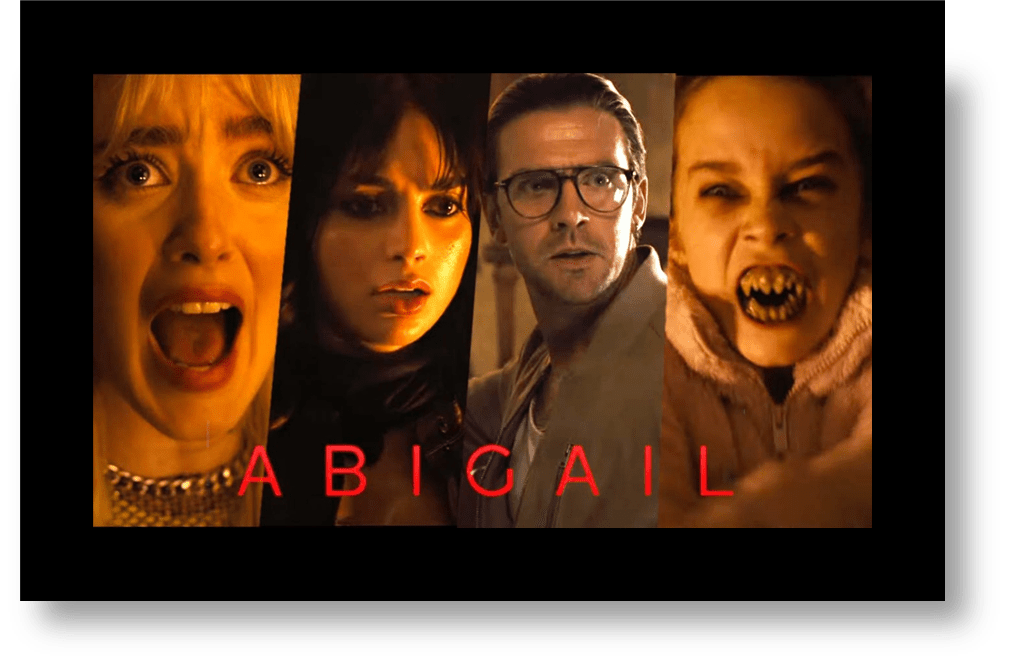

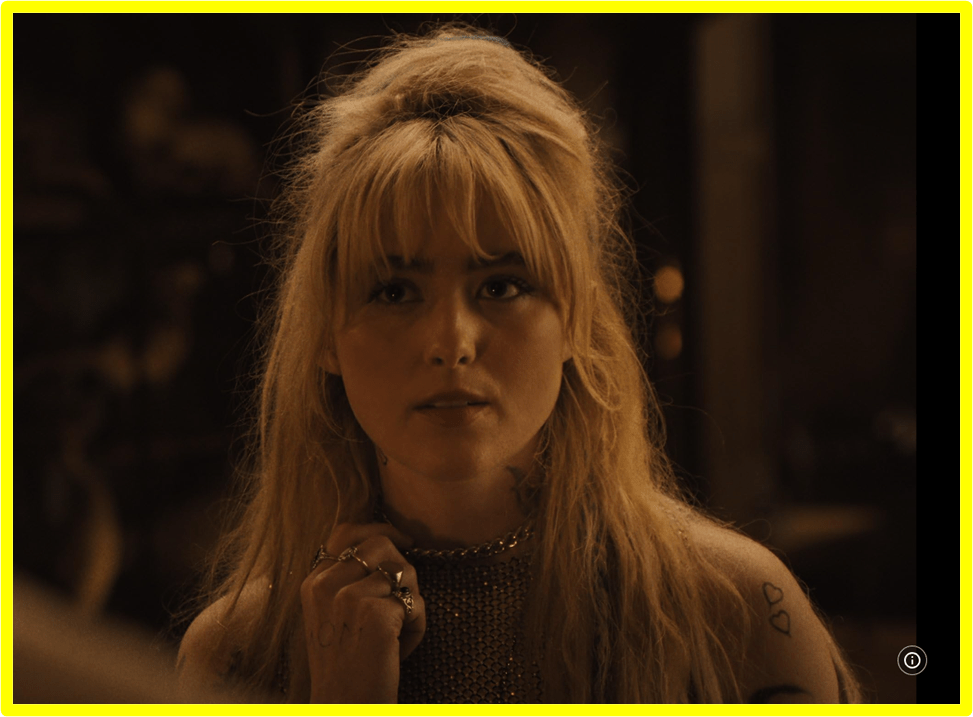

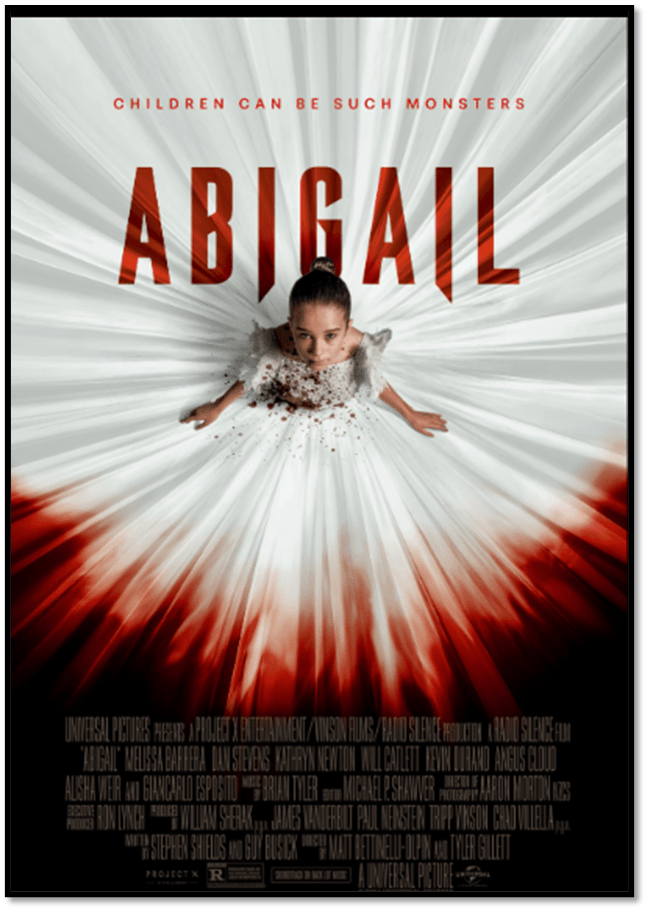

I am going to test that to day by going to see Abigail (2024), a remake of the film Dracula’s Daughter (1936), but ever so much more sophisticated in its technical range of evoking horror. However, if we look at the shots in the film poster above, while the two at each end may be said to be meant to evoke fear (empathetic terror with the screaming woman, reactive to the girl-child vampire with its exaggerated feral features), the two shots in the middle evoke that sense of just-sensed ‘nervousness’ . The symptoms seem to be a slightly exaggerated parting of the lips, a degree of glimmering perspiration and eyes open to a much greater extent than might be the norm when we are merely looking at something and not reacting to it. Yet the symptoms are as much of a necessity for alertness as signals to fear that freezes or causes flight or fight eventually.

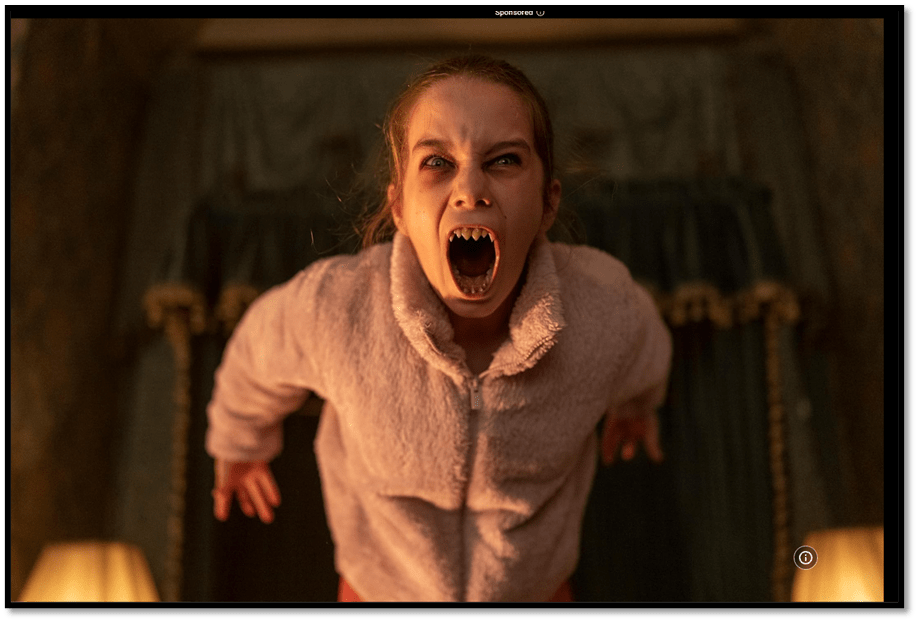

In a sense though, it is the degree by which a horror film evokes ‘nerves’ or nervousness’ that really charts its most important aesthetic effect in modern cinematography. The fear in others is too over-the-top and stereotyped and the stimulus of that fear of too strained a hyper-realism because of the success of digital manipulations. When they don’t fall so far over-the-top to be laughable (for strained and unreal) or disgusting (merely bathing things in over-sticky blood. The eponymous child vampire, Abigail, feels from stills to be possibly of the first kind, though the effects of flight at you, of a face of ambiguous age and dissonant with body features and size and the feral vulpine teeth (a range rather than two prominent fangs).

But the supporting cast, setting themselves up as Abigail’s wet supper, unbeknownst to them, do look as if they can and will allow us to live on our nerves – half excited by their youthful allure and naughtiness – but also nervous of the way that they live in hope of a better life, of some fulfilment, whilst being, as we know – we know what kind of film we have come to – doomed to something less fulfilling, except for the monsters and supernatural forces that will absorb them into itself.

That’s nerves. It is a state where we almost dream both of our ordinariness but dream that ordinariness as a matter of what is attractive to see. We all want to be in a group of beautiful well-dressed people, with a mock-romantic allure of criminality, finding themselves in place that awes them, only for later to find that they cannot settle there, and that perhaps the place will take over you rather than you it. Perhaps you will never emerge from the thing that once gave you hope, but that you became aware of as something potentially not what it seems and eventually terrifies you to fight, fight or freeze (and kills you whichever becomes your fate in the HPA axis lottery).

Meanwhile the monster is no less a monster and no less toothsome and feral but isn’t really the problem.

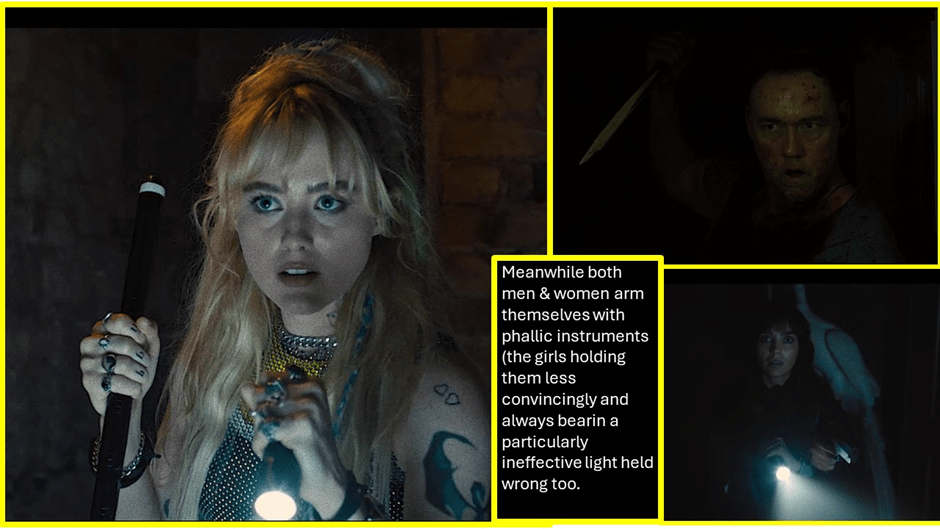

Indeed looking at the picture above I wonder how many parents sometimes see their daughters like that, even as a relief from having just to LOVE them without nuance. But, after all I am trying to argue that is nervousness the horror film exalts. Look at these moments, the monster probably let lose when our charismatic ordinaries (so much as we see ourselves) set off on a search of that they fear, with the regulation phallic instruments for men and women (baton, knife or gun) and, for women always an ineffective torch they don’t seem to know how to hold.

But by now ‘nerves’ are beginning to create wider eyes and even more parted lips. There are moments before that where I merely show my nerves by playing rather aimlessly with my necklace.

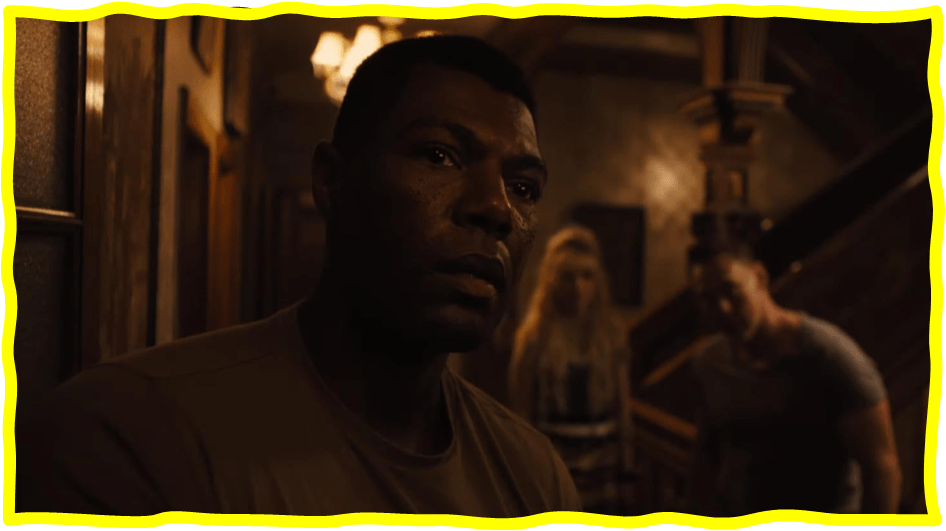

Nerves sometimes are a kind of question we ask the world about how familiar we actually are with it, even more obviously with this man, who seems to think everything he believes about himself to be slipping away. And that is , after all, what really makes us, ‘nervous’.

It is a state of anomie and alienation. Even if we are in a group, the members of it seem to blur behind us, as they do as a result of the sharp focus on the one male actor alone here, pushing the group into the obscure fuzz of the surroundings as I prepare for all I am to possibly fragment and fall apart, unless I (but I aim to) ‘hold it together’. That is yet something else being nervous asks!

But let’s see how Abigail stands as a test case for my thinking. I will mount this blog. Geoff and I see the film at 3.15 p.m. at Durham in Odeon (what come out of a horror film in the dark – no chance!). What I don’t expect is catharsis – purgation, cleansing, religious grace following from purgatory or morally stoic enlightenment?

IMDb describe the plot thus:

After a group of criminals kidnap the ballerina daughter of a powerful underworld figure, they retreat to an isolated mansion, unaware that they’re locked inside with no normal little girl.

I will sum up my afterviews below under the title:

So what was the film actually like?

My expectations of this film above turned out to be incredibly wrong, for this is a film of genre-mix and subversion of expectations based on norms

It isn’t that this isn’t a film ready to use stereotypes of both horror and mystery genres, for it plays with the notion niot only of being a remake of Dracula’s Daughter (1936) but of an Agatha Christine’s thriller, And There Was One, a copy of which has a spoof role in the plot. The Dracula’s Daughter issues are minimal, the vampire father being a rather weak afterthought, although there is an eeriness to Abigail’s line that ‘This is the room in which my father made me’, that seems to feel lie a recall of parental abuse, together with a whole range of patriarchal references in the pictures and art of the deserted manor. Neertheless there are hilarious moments where the vampire-killing modes of the old genre are mocked in beautiful visual jokes, as below:

Of course, there are too parts of the plot when the women signify only a deficit as effective carriers of necessary aggression in order to survive as a human being – which is what I suggest about the stills I saw where young women are seen holding the torch or phallic weapon (gun, baton, stake) ineffectively, but the film works best when you see it as continually turning cycles around the notion of sex / gender / age / vulnerability stereotypes. The criminal gang is led by men but women come out on top. The plot is about exploiting the vulnerability and fear of a young girl until we find that she is not the victim of that plot but its instigating protagonist. Much of the fun comes of the inversion of tropes where women are subjected to fearsome stalking to the reverse.

And Abigail works too because of its fine use of the Swan lake motif, a blending of White and Black Swan in Abigail herself as both Beauty and the inbuilt Beast, Virgin and rapacious appetitive Whore in order to subvert these categories. There is I think a rather clever irony in the film poster legend that reads ‘Children Can Be Such Monsters‘, for the interplay of adult and child interests, the play of the supposed strong and weak partners in age-difference relationships are continually being evoked, overturned and reversed

The terror element is nevertheless openly played for subtle laughs (laughs that almost create a Brechtian alienation (or distancing) effect), though gory enough. What remains is the play on nerves – on the run up to imagined catastrophe and reversals of fortune. And much is made of how the responsibilities of women need seeing in the round as with men rather than being focused on the care of offspring. On the whole women alone are the instruments of revenge for abused children, even when they colluded in the original abuse, but men are just plain awful.

My hunch about a charismatic group threatened by a monster turned out wrong, for there is nothing about the mock gore and terror of the vampire threat as bad as the threat each of the group poses to each other. This is a very anomic group of betrayers and double-dealers whom Abigail is perhaps serving right for past perfidy as she seems to say to them. That is particularly so when we realise that though Abigail thought she had set up this trap as a vampire’s feed-fest, finds it was actually set up by the man she thought served her in order to usurp both her and her gangster-vampire father. And sometimes men are seen as vulnerable to female threat, even rape, as Dan Steven here and ultimately:

Of course, it is all a lot of silliness, but the sex-gender reversals raise it well above the intellectual nullity of the usual run of Gothic-horror-mystery into a film worth seeing, enjoying and even think about more than I do here. As a genre it works by making you nervous and making you realise that what most of all makes you nervous is when things go neither your way, and even then not in the usual manner of going the way of someone else. It is a intrigue of nerves this film. Most of all I think when you realise that the monsters in it have more of what matters in them of reflexive interest in real human achievement and ethics than the humans.

I loved it in a way. I certainly did not feel the afternoon wasted. Neither did Geoff.

So, now ending here, I need to return with much love

Steven xxxxx