Describe something you learned in high school.

Remember, of course, when you read this that I started ‘High School’ [not a phrase used in the UK then much] in 1966 and at a Northern semi-rural UK grammar school where conventions and ideological rigidity passed themselves off as the nature of things.

But the idea of becoming an actor set in deep in that rigid place alongside the rigidities, and sometimes, as I want to show, contradicting them. Now, when I look back, the desire to act someone else seems much more to do with what Rupert Thomson calls a ‘dream of leaving’. In school, I felt that just being the role demanded (‘be a man, my son’) of me a more onerous form of performance than to pretend and even more to become, at least in the allowable interstices of the rigidities of that world, any object I pretended to be and which allowed me to be my own subject of internal exploration and external experimentation.

Yet conventions put up resistance. They still do. I learned that male roles were enacted even by cis male people who did not see the world as performance at all then; that young guys (guys never indicated girls then) around me made up the role of the ‘man’ they tried to be before they enacted it, played a script cognitively embedded, and modelled by admired figures in fiction and film or worked up from ‘real’ men in their lives, or just passed down in social ideologies. You try hard, for instance, to learn how to play ‘hard‘ as a man before you enact it successfully Only then can you forget all the practising and think of harness as an innate quality you always had. I never got there.

There is not much authentically ‘hard’ in me, except a character I make up for usage sometimes, circumstance demanding. But I want to linger on that phrase ‘make up’. Of course, I use it to talk of the invention of a persona or role, but as I got involved in theatre, I learned more and more, on top of understandings that had been there a long time already, that the meaning of dressing up and manipulation of appearance through cosmetic makeup was part of the process of becoming, at least in theatre.

But I never, quite then, and still now to be honest, got over a taboo against men using cosmetic makeup in real life on their faces, when it is very common these days in young men whatever their sex, gender or sexuality self-identification. Though happy to make up for a role, offstage makeup remains a no, no for me. Even using moisturiser is a no, no. This shows I learned that not using makeup is also a kind of makeup and one I tried hard to master: a kind of subjection of the skin to hardening processes of exposure to environmental influences,natural and otherwise, to things that make any face, of whatever sex/ gender, rugged and less flexible, more soft to touch, appearance or exposure to labelling.

I think I still bear that duplicity in and to truth. I am writing about Rupert Thomson’s latest novel How to Make a Bomb, and I think it is replete with such questions about every role in our lives. This is particularly so in the novel for cis men, and more so cis heterosexual men as appear in large in the novel, of how to make up / invent and be the man you wish to be or are told by ideology and model you want to be. That will get explored in my blog on the book.

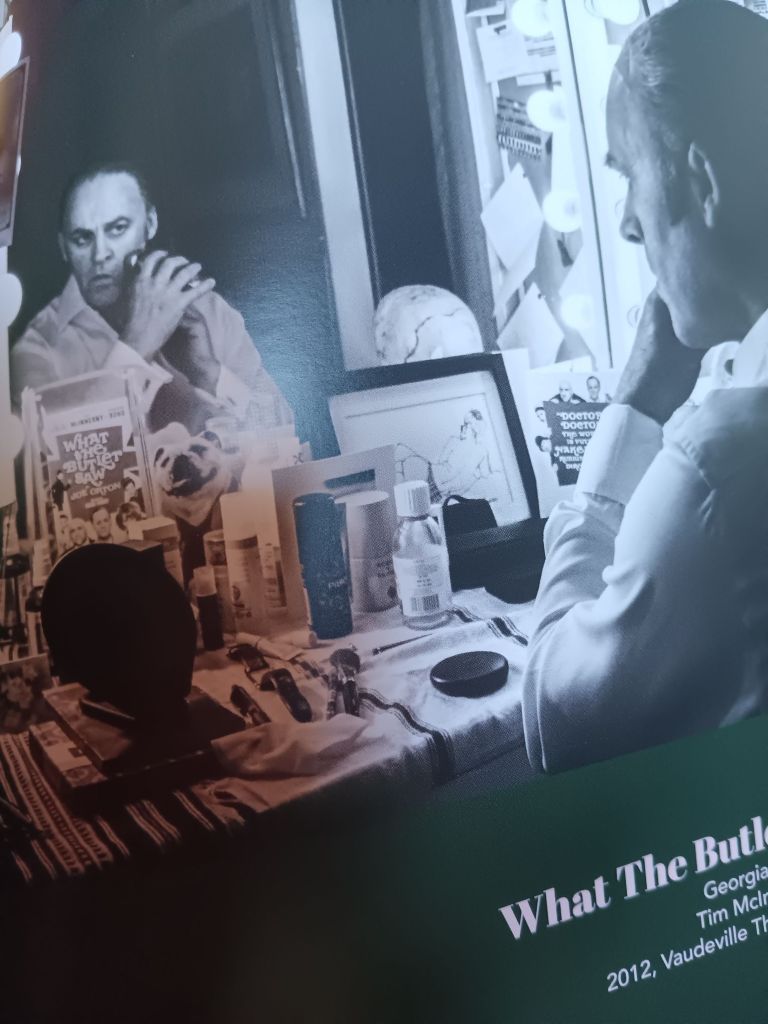

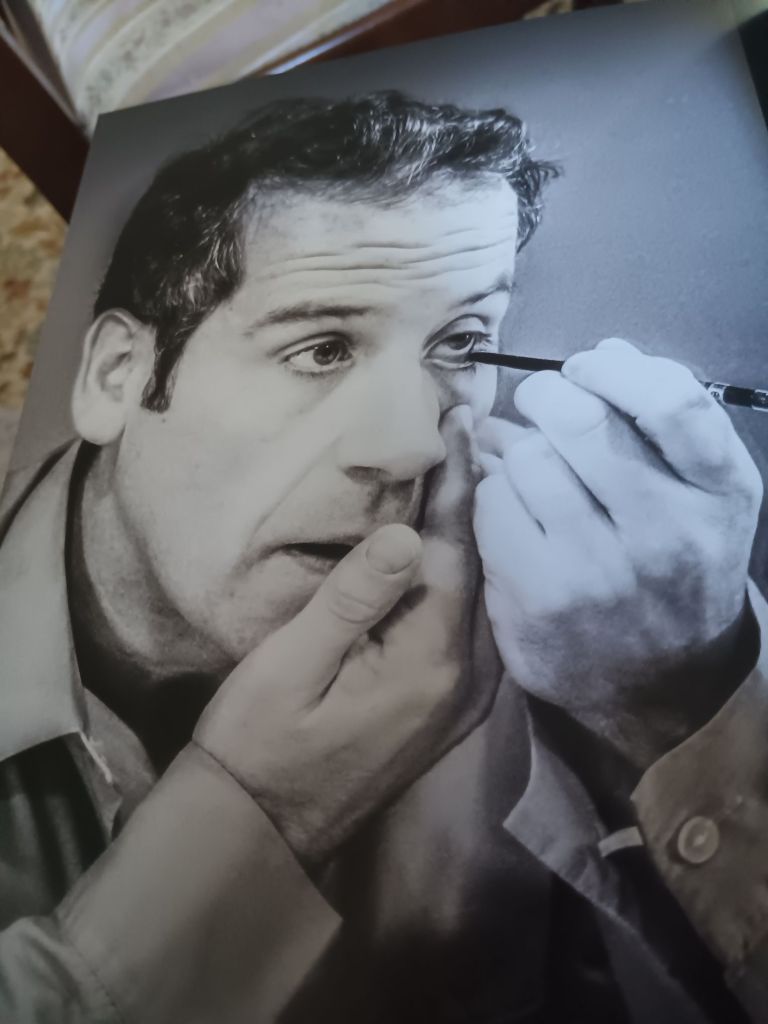

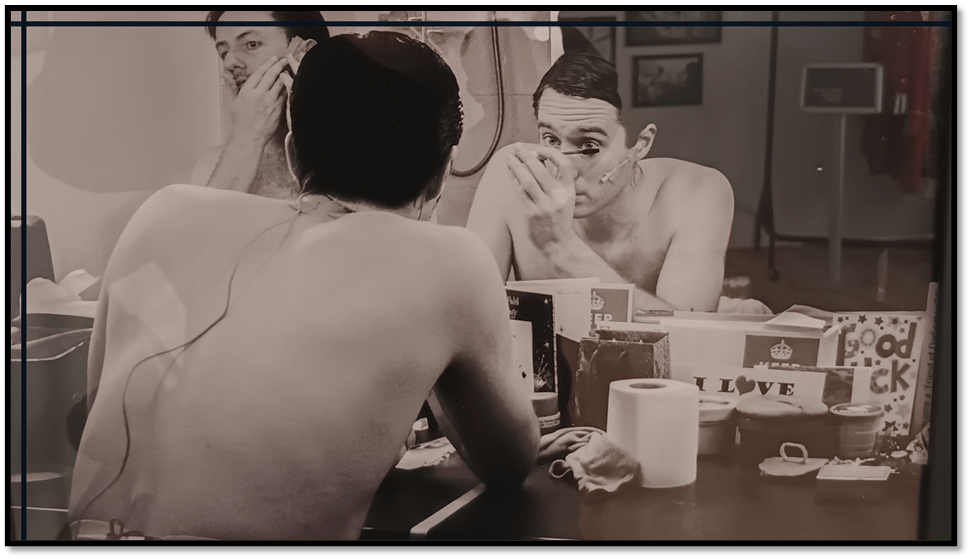

However, my signed copy of Sophie Teesdale’ lovely book Dressing Room No. 1 arrived recently (see my blog on the exhibition based on the book at this link). These thoughts that stem from high school were prompted towards the evidence of revival constitited by this blog by wonderful scenes of two men making up to play roles on Joe Orton’s What The Butler Saw.

Nothing in these photographs show Tim McInnery and Jason Thorpe respectively attempting to feminise their appearance for their stage roles – masculine roles as they are- but even when Tim holds an electric razor for shaving of a type usually used only by men, the appurtenances of conscious makeup: a large lit mirror, mechanisms of make- up application, manual.manipulation of face confuse the sex/ gender roles portrayed, at least in this backstage liminal space.

But they show no more than I knew in high school. Men make up their faces, whether they use makeup, even moisturiser, or not. Performance never stops. Liminality of sex/gender occurs elsewhere than backstage or in dressing rooms, where clothes play a part too. There is more choice here than we think and a vast deal more than J K Rowling pretends to think (thinking not being her forte), if we allow ideological inflexibility based on an O-level grasp of what we call biological sex to relax.

But note. I still need to read, let alone blog on, Judith Butler’s new book: they the master of the theory of social performance.

With love

Steven xxxxxx