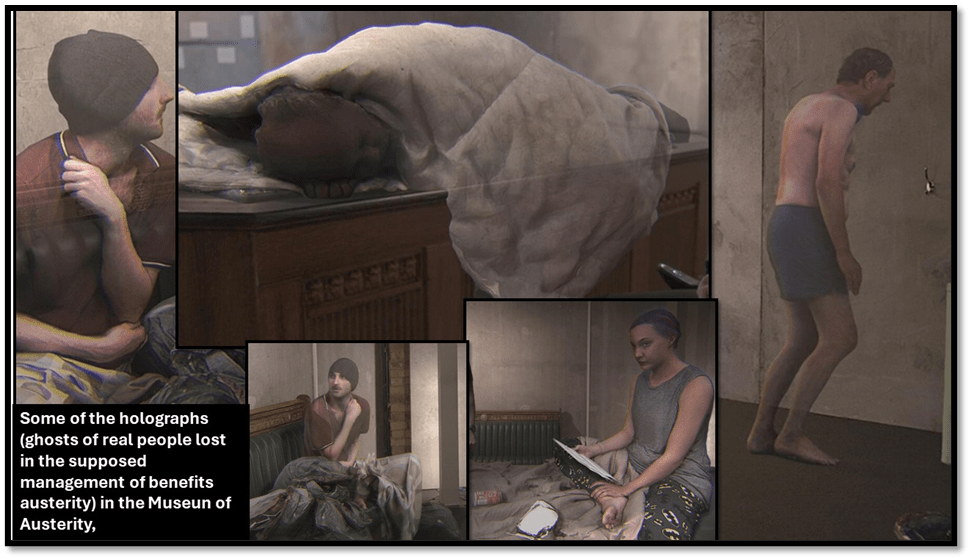

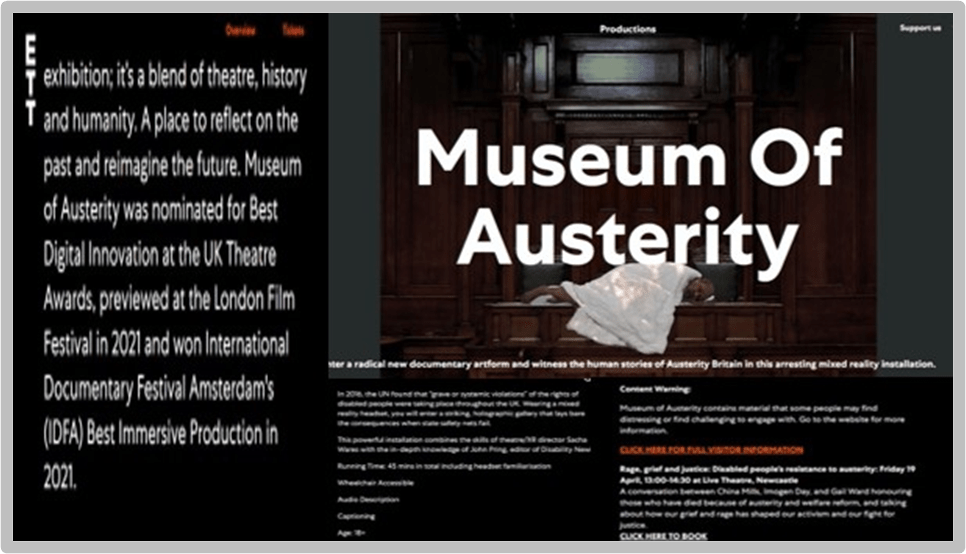

Yesterday I visited with my husband Geoff, the Live Theatre at Newcastle, to see a show that has received multiple awards for its contribution to the art and functionality of different modes of social art – documentary, immersive theatre and digitally innovative theatre. Audiences don digital headsets and then enter a room of unadorned stands – these room spaces vary according to the setting, as my internet sourced pictures show. They are deceptive those pictures, by the way, for only wearing the headset do you see the static three-dimensional holograms on the different stands (some holograms merely stand against a wall or lie on the floor, one older male hologram lying in the filth he died in, on the street still carrying the bag of goods given to him by Lidl in their bag, with a loyal dog by his side). Without the headsets, you can’t see these figures, though. However, because the sets are bifocal, you do see the real rooms that are their archival place of the figures’ virtual being for the moment. You do not hear their stories without the headset either; it is told not by them (for they are dead and that respect due is paid to them, not to appropriate their personal stories) but by surviving relatives.

The stories don’t get triggered in the headset until you are near almost to touching the spectral figures and the stories resume where they left off, if you turn away to another figure or for emotional relief, when you get close to them again. After 35 minutes, I am told the images fade to be replaced by the real names in commemoration of these real people now dead. However, no one in the set of people I entered the third floor studio with lasted the full 35 minutes, so harrowing the stories. So appealing for empathy and warmth, too, are the still and ghost-like figures, who at times seemed they would be cold to the touch. The stories end where they end with the circumstances of their death, if you get to their end.

I often reflect back on my period as a social worker in different specialisms starting with Older People (well before I was, as I am now, one myself), Primary Care Mental Health, Severe and Enduring Mental Health, Learning Disability and Physical Disability and a Worker with Carers (and finally a Teacher of Social Work). Those labels were then and are now nonsense – neglecting the interaction between all the labels attributed to persons and the differences that each person presents as a ‘problem’ or ‘problems’ to Social Services and the Health System in various of its over departmentalised appearances.

Issues like Mental Health in particular interact with all other issues, often tied together by responses to myriad forms of stigma that reflect upon each other and the pressure not only of the ill-fortune that brings people to need services from the state but the pressures on mental health the state itself exerts. And it does so most, in my experience and from various testimony (think of Ken Loach’s I, Daniel Blake) through systems of the state that the populace are entrained to believe over-generous and competent but in fact austere in policy and practice.

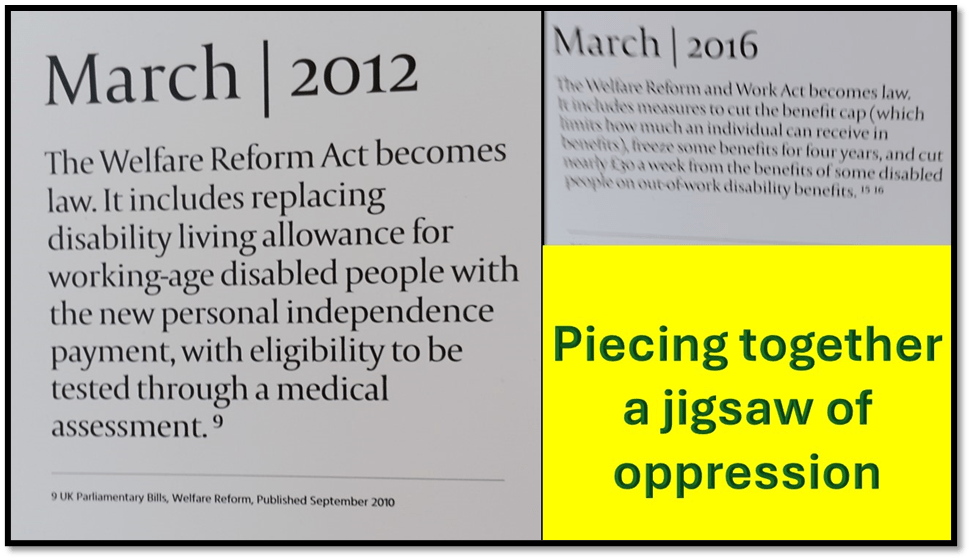

The particular period in the history of the social ‘care’, David Cameron talked of as the period of necessary Austerity (where a few experienced the very opposite of Austerity and the many were encouraged to be smug in their minimal earnings). Austerity always meant austerity for the few defenceless to the system, despite its leaning to the meanings it had under the post-war Labour Government.

This exhibition made me feel again my years as a social worker – especially the moments of hopeless sadness for people in need the state made it impossible to help, and trained in their expected role of fatalism, such that the person in need of help co-operated in making helplessness a fait accompli. Some of these people died at their own hands and /or starvation, following the receipt of penalties from the benefits system and health, housing and social care failure, others as a result of harmful self-medication by alcohol and yet more neglect in the community.

When I was a social worker, the biggest lesson I learned and tried to teach was ‘Take Responsibility’: not a lesson directed, as itvtoo often is, at the person so depleted of resources and what we call capital of all kinds, including social and emotional capital, but at the worker who can only mentor people to responsibility in the long-term and then only when all those resources are beginning at least to be marshalled for these people. In terms of the prompt question of this blog, all of the times ‘when (I) didn’t take action but wish (I) had‘ were about failures in myself to take enough responsibility, or for not insisting on that in student social workers and team colleagues.

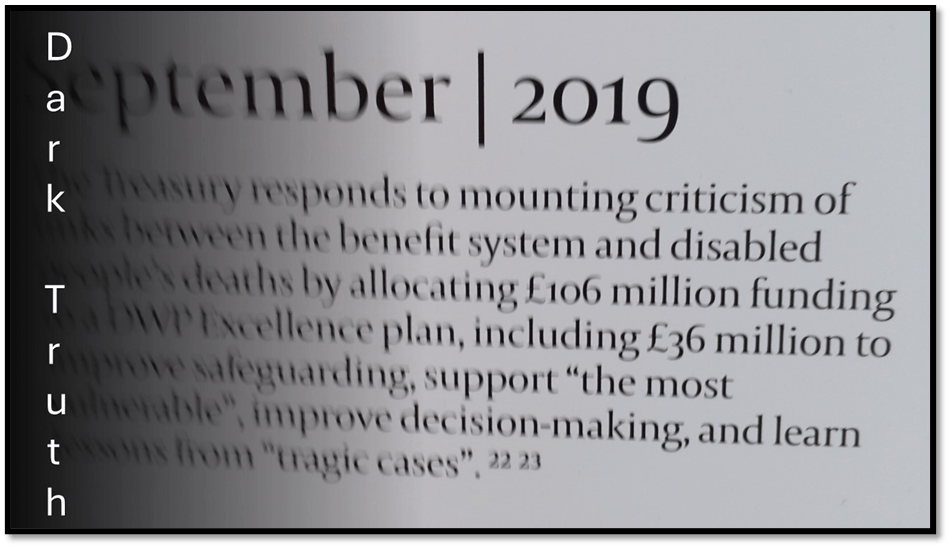

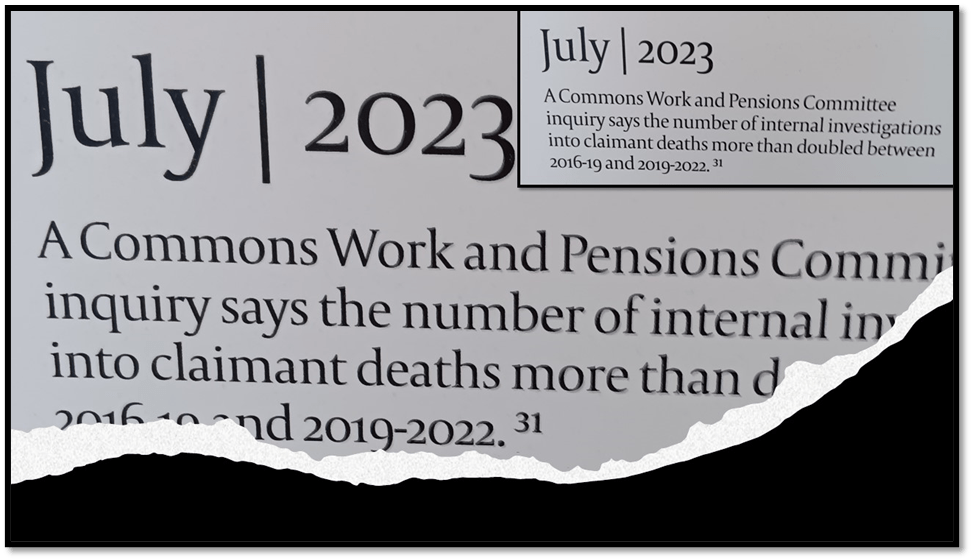

For the very systems that claim to induce responsibility for self in what are often called service users do the opposite. In my experience, they have long done so, but as this exhibition shows too, we have passed through a dark period. This is revealed in the pieces of audio from parliament that pepper and insult the figures and you from parliament: Ian Duncan Smith, Therese Coffey, and Boris Johnson with their empty moralities and even emptier sympathies for ‘tragic cases’. They were, after all, all foreseeable these deaths; caused by the insistence on not seeing the person, only the ‘problem’ they posed to a system inclined to act as a miser of the national conscience, retributive vengeance and a whole load of contradictory other things. There is a timeline telling this story in the foyer to the exhibition.

Those ‘tragic cases’ again. They weren’t few. Every person amongst the holograms – a former nurse, soldier, carer, willing volunteer in social causes, private artist and poet – could have been assisted. They fell in dark times. In the exhibition, some visitors, I was one, seem to want to get near these virtusl people – to unconsciously perhaps make up for the neglect they experienced. The issue is that it is the nature of exhibiting persons as objects of the consequences of policy you cannot do so. However moved I actually felt, and despite some gestures displaying it, I still could not reach the figures. It is heartbreaking to see both hologram and non-hologram as part of the exhibition, as you bypass other close listeners and notice other figures still held in lonely helplessness without a warm-blooded listener.

Moreover, if I look beyond the young man attended by someone in the picture below, we ser a man unattended.. Hearing the story of a man debilitated by physical and then increasing mental disability and imagining his death at home, his body unfound until well decayed is one thing, seeing him seek the support of a wall in lieu of a body is another. Here, he approaches a fridge, which the story tells us had nothing in it when he died. In the Newcastle version, the fridge is not used. The analogy is too near, perhaps. For we are that empty fridge as we stay ‘unacting’, even if only by enacting protest: empty and still uselessly cold.

And then there are the numbers for that period, collected only recently in July 2023 which prompted this exhibition, but a surprise to no-one in services, using them or caring or supporting someone who does so.

You can read the DWP letter about Personal Independence Payment (PIP) over a young woman hologram’s shoulder in the Newcastle exhibition, although the young warm-fleshed man in the photograph below cannot at his show, the figurd is too near the wall. There is something strange about circling people as ‘exhibits’, nevertheless, as dead items in a museum, and ones that are more than actual illusions because they refer to distinct people, but not much. This is part of the complication. Is looking enough? Is feeling enough? Not really.

After all, all the law tightening benefits administration and denial was passed in my lifetime. Indeed, it was quite a short time ago relatively and tightened after open debate. What did I do? Should I have done it differently? Of course, I did less than needed, and of course, I should learn better. One mother says of her dead son that she did not blame politicians, for they only do what people wish them to do. There is a truth here in which we are all responsible, even without letting the abysmal ideological nastiness of a ‘Nasty Party’ off the hook.

That carer tells of her son leaving in his flat with his starved body items that were bagged in bin bags by the authorities to give to her. She mentions watercolours painted by him. As I sat by him, I saw one about, as it were, to tumble from the bin-bag. However, because, merely part of a static image, it never will, of course. It was beautiful, the picture I glimpsed, as his mother said it was.

In a photograph of another version of the show (see the picture of it below) I cannot easily see this element so clearly. Neither could the young warm-blooded figure standing over hologram and at greater fudtance from the hologram. You can do this in this show, stand over people, and suddenly realise there is a lack of respect in doing so – though not intended. That is why I sat with him. As I recreate my motion imaginatively, I see those papers again near where I would have been sitting, even in this photograph.

Clearly all this can be hard going, where art touches on social realism so closely but is still art, still a construct. It is so even in a carer’s story told by a Dad just on a plaque outside the exhibition room. There is drama in a father holding up his son’s ashes to declare a present absence caused (yes, caused) by the system calling for that presence to be seen only in a manner it dictates. There is something worse in ATOS representatives caring more for their job than the injustice committed here and not attending an inquest.

Do we identify with the dead, we who are living, in these stories? Do we identify with the disadvantaged, marginalised, and disabled, we the entitled or feeling as such? Certainly, some of the figures, like the woman below, are identifiable as like ourselves or our relatives. What matters is that we identify with the one plaque that appears in the hologram room (not as a hologram and seen in the picture below).

It reads:

There is reliable evidence that the threshold of grave or systematic violations of the rights of persons with disabilities have been met’.

And note these aren’t really people WITH disabilities but people who are continually being further DISABLED, even unto the disability of death, by us – by a system of systematic violation in the name of fairness that we passivdly support by being passive. The system will always blame oddball scapegoats in ATOS, the benefits system, and throughout health and social care and resource provision. That is an illusion. Like it or not, we create the systems of governance that necessitate those people, talking of fairness when we mean a lack of disturbance to the currently entitled.

The hologram below shows a man, collapsed in death in one of the shows. This show was held, clearly, in a venue where civic authority matters. It must have been a powerful reminder of the responsibility of authority, however plushily it seats itself on cushioned leather behind a grand table, having entered through even grander doors to do this sitting in judgement But I am glad this was not the venue in which I saw the exhibition.

Where I saw it, the same hologram was more like the situation below. I also sat near to him, gazing but not daring to touch, not that I could, for the flesh is illusion in reality here, not just in rhetoric. I sat by his , I sat by his feet. And then I sat, feeling humbled, by the feet. I should feel humbled for I could have, surely I could, taken responsibility to help him to stand when he was a living, breathing man, such that he could find the strength to stand autonomously later.

Once reassembled in the foyer, I saw my husband, sweet man, speaking to two young women equally moved but from their conversation engaged in current action against poverty and oppression by state systems. One said how devastated she was to see the show but also said: ‘It should be compulsory to see it’. Truth-tellers do not get a good press and whistle-blowers less so, as I have found to my personal cost many times (loss of job often) but nothing is risk free. Ethics is a prime example of risky thoughts, feelings and actions, and the pursuit of justice, other than in abstract, a dangerous thing. Of course, we must do things differently, but most of all, we must do something.

Please see this exhibition if you can. It is wonderful.

With love

Steven xxxxxx

One thought on “The many times when action matters in social work. Memories whilst Visiting ‘The Museum of Austerity’ at Live Theatre, Quayside, Newcastle on Wednesday 17th 2024”