What place in the world do you never want to visit? Why?

I would not visit the Tundra in Alaska. I have not Jamie’s grit or the steel-edged beauty of her imagination. But in her I can see a reflection of it. The feelings it raises are complicated. Of course, worthwhile experience always is.

I am just beginning to read, for complicated reasons, Kathleen Jamie’s book, Surfacing, in which she records in one long essay in that book a visit to the Alaskan Tundra. The visit was timely because the permafrost on which a way of Inuit life was built was perishing. Built is the right word for nothing during the reign of the supposedly permanently frozen ground could be buried, even as a foundation for building, under the surface of the ground, thus also hiding it from view. Houses had to be built on stilts, pipes for the evacuation of sewage flows had to be fashioned overground, and waste could not be buried (even large mechanical equipment past use), the way of the West otherwise. And as the frost softened and liquefied the Tundra earth surfaces, the stilts of the houses sunk unevenly, walking became more jumping from tussock to tussock, and a landscape was more truly a waterscape.

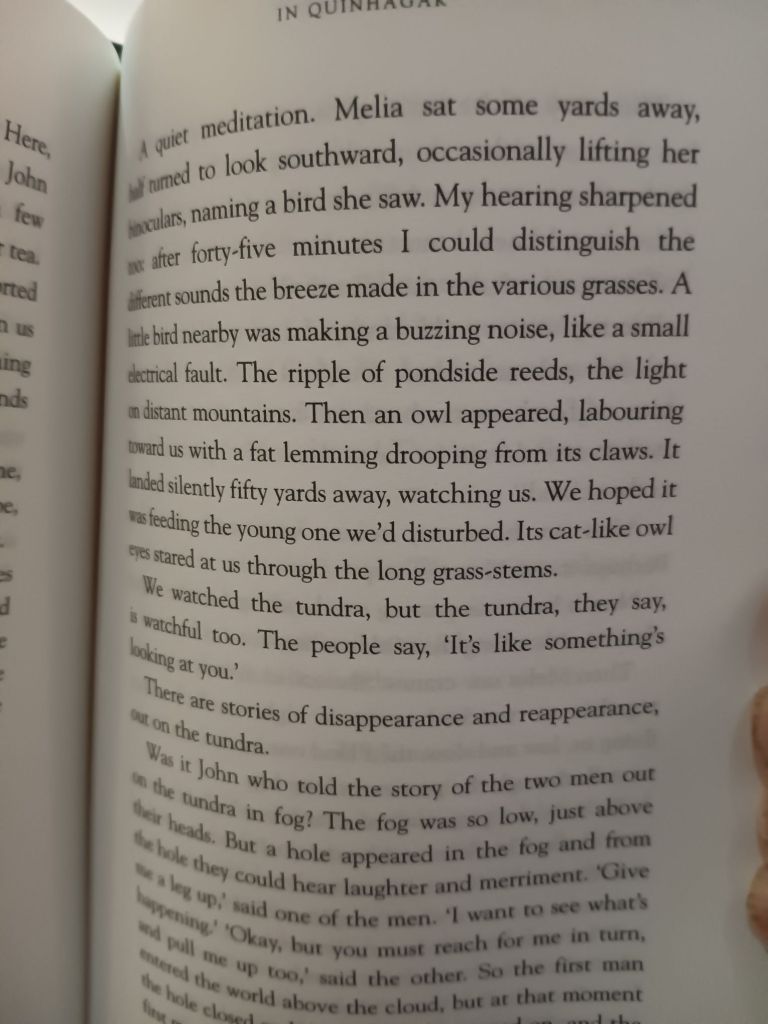

The view to sea and land on either side of Jamie is often reduced (thought that’s the wrong word) to an expanse of light in which seen objects were difficult to name for distance betwen it and the viewer was not easy to estimate. A mobile thing in the distance might be a small woman squatting or a large bear tearing off strips of blubber from the remnants of a stranded seal. In the end, it turns out to be a raven, which, startled, rises to the skies.

Milton imagined Hell as ‘darkness visible’ but Jamie’s descriptions evoke an idea I find more frightening still, ‘ lightness visible’: a state of visually exhausting expansiveness in which objects get lost to the point of irrecoverability. I used to find the poet Vaughan’s line more frightening than reassuring about eternity: ‘They are all gone into a world of light’.

Out of the dirt and mud, which the ground becomes without permanent hard cold to hold it still, dry or stable, comes the excreta of a village with its abandoned social practices related to names from a language lost to modernity and global English. Often, these practices are those of a lost female tradition, a tradition barely recoverable from any image of the feminine used in modernity, whether it be ones that are thought regressive or contemporary and feminist. A woman’s knife and the implements of female power, agency, familial discipline, or violence are awesome things in this writing.

Language is so important to a poet, and its power is to name in its nouns and to build relationships in its syntax. Yet this Inuit people, the Yu’pik, have been taught at schools and by parents looking beyond the privations of their hard past to consider their native language a ‘dirty language’. Nevertheless, the words for common loon and crane are in that language ‘soft and irresisting sounds, like the Tundra in summer, all ‘qs’ and ‘ka’ and ‘ochs’. Perhaps for that reason, these landscapes still remind her of Scotland.

Read the passage above. In Jamie’s prose, landscape, waterscape, and airspace are all inhabited and heard and otherwise sensed, not just seen. What’s more: are we looking at it, or is it looking at us? It’s watchful of the treachery we bring into it. Humanity may come to dig and recover the buried and frozen past, but only after it has destroyed enough to eviscerate its innards and lukewarm them up to a point beyond their ancient chances of survival.

Yet I do not think I could discover in the Alaskan Tundra what Jamie does. I will rely on her awesome authority.

With my love

Steven xxxxxx

One thought on “Kathleen Jamie chose to visit the Alaskan Tundra and help with an archaeological dig. Would I?”