What is your favorite restaurant?

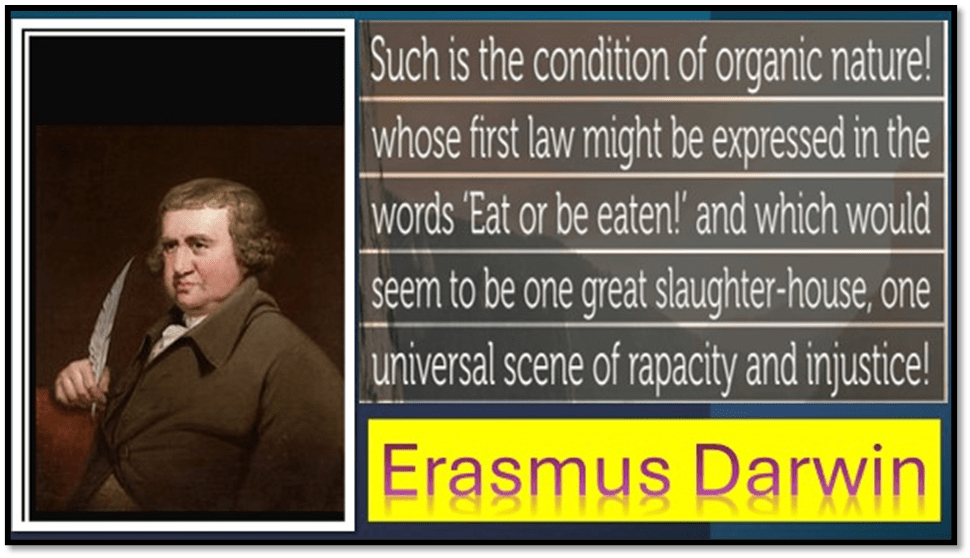

The Duke still exists on Duke Street, as does Davy Byrne’s eatery, but I do not know if The Duke in which we know Joyce dined regularly was also the ‘Burton restaurant’ referred to Episode 8 of James Joyce’s Ulysses. That episode is usually known as the Laestrygonians, since it paralleled the episode in Homer’s The Odyssey, where Ulysses is beset by cannibal giants of that name who murder many in his crew. It is a place where if you aren’t eating, you may get eaten. That analogy is what fires the description of my favourite restaurant in literature, with its version of a statement of Erasmus Darwin, the pan-intellectually curious father of the more famous Charles Darwin, of 1800.

That statement in the collage above is mirrored in Silas Wegg’s version of the meaning of competitive capitalism in Dickens’ Our Mutual Friend: ‘Scrunch or be scrunched’. In Ulysses, Joyce echoes the phrase in Leopold Bloom’s racing consciousness as he leaves ‘Burton’s’:

He backed towards the door. Get a light snack in Davy Byrne’s. Stopgap. Keep me going. Had a good breakfast.

—Roast and mashed here.

—Pint of stout.

Every fellow for his own, tooth and nail. Gulp. Grub. Gulp. Gobstuff.

He came out into clearer air and turned back towards Grafton street. Eat or be eaten. Kill! Kill!

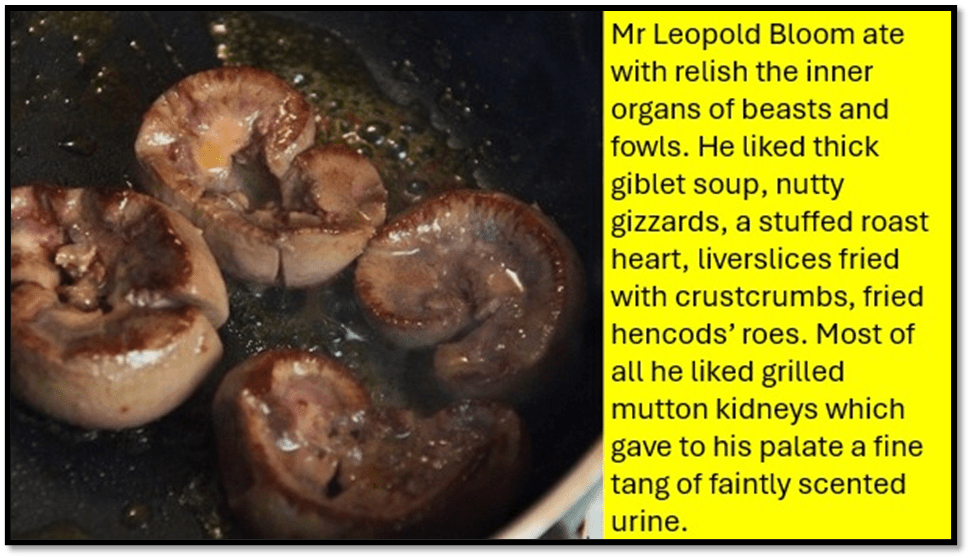

Eating is not necessarily a selfish thing, but let’s continue in the light of that quotations emphasis on selfish competition as if it was and address communal eating later. Certainly eating is sensed first as an experience of individual intake via the embodied senses and mechanisms involved in both tasting and eating (such as the organs involved in humans processing food – plant or animal – from the lips, mouths, tongues, teeth to the .visceral internal organs of food processing during consumption down to excretion of waste consumption also involves. Kidneys are important organs in the book, where the urine they expel becomes an excitement in their consumption. In fact, the ‘good breakfast’ Bloom thinks about above would have included lambs’ kidneys had he not burned them and had to throw them to the cat (in Episode 4):

Yet as he turns into Burton’s restaurant, thoughts of sexual appetite fading from his mind that had arisen there from the scent of fragrant ladies on the street, all he can think of is the violence meted out to the tissue of animal and vegetable by eating, the flavour in his nose (for smell and taste use the same mechanisms) of seeing men eating and, in the Laestrygonians analogy with Homer so important to the text’s structure and imagery, men being eaten by huge voracious unthinking angry and hungry giant cannibals.

The Burton is almost certainly The Duke in my view but who in the hospitality trade would advertise this fact if you own a famous eatery in a major European city, given this famous passage, starting:

His heart astir he pushed in the door of the Burton restaurant. Stink gripped his trembling breath: pungent meatjuice, slush of greens. See the animals feed.

Men, men, men.

So my favourite restaurant is this one, even though it be a literary one based on that real place, like so many real Dublin places visited by Bloom on his day of Odyssean wandering, before return to less faithful Penelope, Molly Bloom, who consumes men too.

It is a favourite restaurant, as long as I do not have to eat at the place as Joyce describes it in his character Leopold’s consciousness of it, because restaurants are too often sanitised of their relation to bodily labour and the collection of tissue that mean that tissue’s death. And with that, we forget the visceral in eating, its violence as a process, and the relation of the internal gain of nutrition alongside the excremental evacuation of its ‘waste’. How glossed over are those processes in the advertising of restaurants, although I note that some answers to this question have contrasted the plushness of some restaurant interiors with the disgusting state of uncared-for toilets, where the waste excretion implicated somewhere along the line in food consumption becomes most evident. But in Burton’s, those processes are too visible to Bloom, as in his sight of a man challenged by even the first stages of processing his food intake:

A man spitting back on his plate: halfmasticated gristle: gums: no teeth to chewchewchew it. Chump chop from the grill. Bolting to get it over. Sad booser’s eyes. Bitten off more than he can chew. Am I like that? See ourselves as others see us. Hungry man is an angry man. Working tooth and jaw. Don’t! O! A bone! That last pagan king of Ireland Cormac in the schoolpoem choked himself at Sletty southward of the Boyne. Wonder what he was eating. Something galoptious. Saint Patrick converted him to Christianity. Couldn’t swallow it all however.

—Roast beef and cabbage.

—One stew.

Smells of men. Spat-on sawdust, sweetish warmish cigarettesmoke, reek of plug, spilt beer, men’s beery piss, the stale of ferment.

His gorge rose.

Couldn’t eat a morsel here. ….

Gums, teeth, and more abstract processes like hunger and appetite, and their opposites: the nausea associated with gut responses leading to vomiting. How like are those latter processes Bloom, and Joyce, show us to those of ‘anger’ and ‘disgust’ that go alongside their super-expression in the fear of cannibalism, of what it might be like to consume the flesh of a human animal instead of a non-human animal or the dying fibre of vegetable tissue. We sense Goya here of Saturn devouring his sons lest they grow up to depose him, as inevitably they must:. After all, a ‘hungry man is an angry man’.

Excretion of food begins early in the process of eating it: as we ingest we also breathe out air stuffed with particles of food that others smell and thus, in a small way, ingest too, spit on a sawdust floor (no longer the practice of patrons of The Duke I understand just as I believe the floor covering of The Duke is no longer sawdust) must carry the ingested back out thee too. And Bloom senses in the atmosphere of Burton’s too the beginnings of decay or rot involved in digestion, and of the piss evacuated afterwards. When your gorge rises you may be nauseous, disgusted (even by an idea) or violently angry . What Bloom sees, he also smells and tastes and the processes involved are both pysical and psychological, az is Ulysses’ disgust at the habits of cannibal Laestrogonians in Homer.

When leaving Burton’s, Bloom ‘gazed round the stooled and tabled eaters’. Disgust sets in and perhaps some anger at his possible likeness to these men, as he also feels himself, perhaps involuntarily, ‘tightening the wings of his nose’.’ Hungry men are angry men’. It is as if what he see in these others includes the reflux of their internal selves and the contents of their prior intake, psychological and visceral into the communal air. It is a human fear of the deepest kind is ‘projectile vomiting’, seen as a symptom that blends the physical and psychological – the body and the contents of its thoughts and feeling, seen in babies as a rejection and projection out of its body of what its parents thought were the love and support (and possibly belief-systems and identities) being stuffed into it.

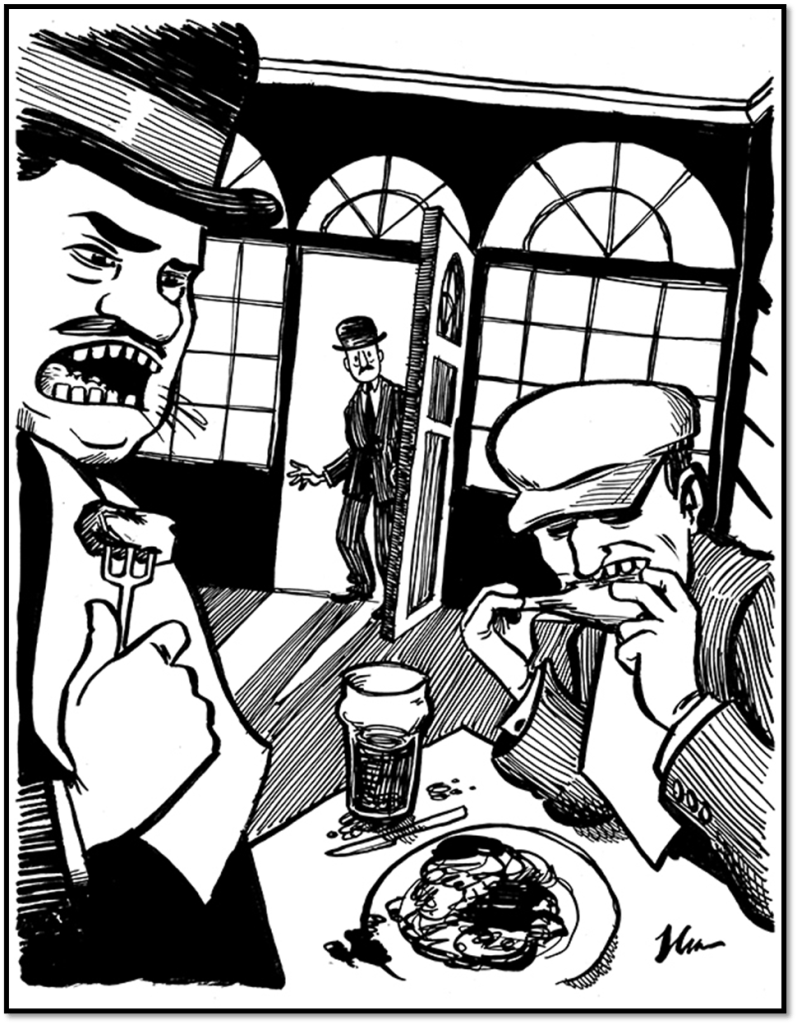

Stephen Crowe’s giclée print illustration of Lestrygonians for a de Selby Press edition of Ulysses, date unknown. Source: invisibledot.storenvy.com Available: http://m.joyceproject.com/notes/080000lestrygonians.html

After all, in restaurants there is, underneath the civilized diner, in all of us perhaps that ‘fellow ramming a knifeful of cabbage down as if his life depended on it’. Okay, the higher the class distinctions, embodied in the actions of social etiquette, the more we target such appearances in ourselves and modify them. We aim less to ‘ram’ food in, as regulate it and our appetite with a more ritual use of feeding implements and ‘manners’. The less also under those latter conditions, will we take our meat, and: ‘Tear it limb from limb. Second nature to him’.

We do not talk with our mouthful, unlike another ‘chap’ Bloom notices: ‘telling him something with his mouth full. Sympathetic listener. Table talk. I munched hum un thu Unchster Bunk un Munchday. Ha? Did you, faith?’. The joke is that mangled words are masticated like food so much that they come back out as words eaten away in the process of their expulsion. Bloom concludes: ‘Out. I hate dirty eaters’. But what makes eating dirty or clean: is it also ritual as Mary Douglas has long told us in Purity and Danger.

Hence, as he leaves Burtons, Blooms thought turn to Communion in the Catholic Mass – to the ritual drinking from the same cup and off the same plate in Communion, muching the body and blood of Christ, but what else:

After you with our incorporated drinkingcup. Like sir Philip Crampton’s fountain. Rub off the microbes with your handkerchief. Next chap rubs on a new batch with his. Father O’Flynn would make hares of them all. Have rows all the same.

Communal eating is another kind of communion, where instead of hosting with food, we host with conversation. Bllom’s thought confounds that, too, with the dangers of too many people earing out of the same communal bowl:

Hate people all round you. City Arms hotel table d’hôte she called it. Soup, joint and sweet. Never know whose thoughts you’re chewing. Then who’d wash up all the plates and forks? Might be all feeding on tabloids that time. Teeth getting worse and worse.

Food is disgusting and watching other people eat and thinking of them doing the same to you is even more so, Bloom thinks. This is so even if the provender is vegetarian because it stinks of the common earth, but so much worse is the pain we ingest of the slaughtered animal:

Pain to the animal too. Pluck and draw fowl. Wretched brutes there at the cattlemarket waiting for the poleaxe to split their skulls open. Moo. Poor trembling calves. Meh. Staggering bob. Bubble and squeak. Butchers’ buckets wobbly lights.

So my favourite restaurant is in fact the place where you get a Naked Lunch, that is a lunch undressed of the clutter of social rituals that clean up and then exoticise the eating and drinking process in an attempt to raise it above the animal appetites in frills and flounces

As ‘The Duke, Dublin’ sees itself now

Come with me to Burton’s. It’s an experience.

With love

Steven xxxxxx