What job would you do for free?

Friend, I do thee no wrong.

Matthew, 20: 14

Didst not thou agree with me for a penny?

Take that thine is, and go thy way.

I will give unto this last even as unto thee.

‘The eleventh hour labourers’, etching by Jan Luyken based on the Parable of the Workers in the Vineyard (Matthew 20) By Phillip Medhurst – Photo by Harry Kossuth, FAL, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7550696

When Ruskin wrote Unto This Last, based on a parable of the just distribution on the remuneration of labour, he felt that he had developed a non-materialist theory of socialism that effectively insisted that there was no binary in the theory of value. Value is, in fact, he asserted the recognition and the time and work / labour consumed in making or collecting, and making it available to others the thing made. The true cost of the thing made is the amount of life it consumed in that full sense of making. And that value matters because value is, in fact, Ruskin says, not only the cost of so much life expended but conversely, of course, the degree of proximity of death accumulated in a person. Work and time both are valued in terms of how much organic life and death they embody and dissipate.

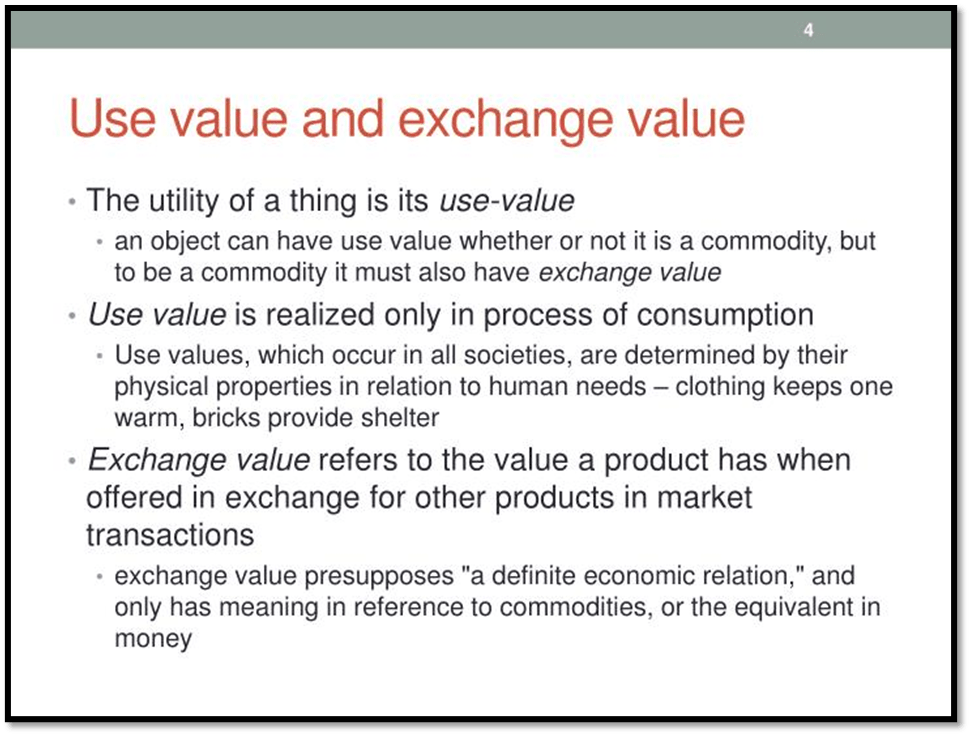

In Marx, the value of material thing was divided by its use value and exchange value. It was the relationship between these things that determined for him the distortions of capitalism. Exchange value can be distorted by manipulations of demand for it like advertising. Hence, a commodity is not necessarily valued for and in itself but in its crested aura of desire, built upon association with other things wanted by people. The usual choice of the image of the desired are things offered people power, status, and/or pleasure, but in fact gives access to none of the things with which they have been fancifully associated. Of course, there is a fine line between giving information about why a thing has use-value and merely massaging its exchange value in the interest of surplus value or profit.

It is not that Marx did not value individual lives in the analysis of the classes engineered by systems of value creation and its regulation. That’s so whether they be relations of unequal ownership that drive feudal organisation of land management in the interest of the current landowners, or the mechanisms of capitalism to drive the production of surplus value to be appropriated by capitalists and their allies. But, his early views about alienated labour were dropped in the rigorous science of his book Capital, according to Louis Althusser, and interest in the sapping of individual lives in things of no use-value to them by the appropriation of their surplus value by capital was turned into an economic maxim rather than an appreciation of what the work and time of each person was truly worth.

Ruskin is thought of as a spiritual writer, but his Unto This Last is actually an attempt to see cost in terms of the wear on the body, embodied energies and embodied capacity to sustain life and suffering death only at a time dictated by systems of the body and meeting its needs and support for meeting those needs.

There is in Ruskin nothing that is done for free, even waiting upon events. It all costs a certain amount of life used and death accumulated. Energy expended in the work of hand or brain is notionally an additional wearin away of life and its passage into the shadow of death. However, not to do things for ‘free’ is equated nearly entirely in developed capitalism, with receiving a monetary equivalence to that value. And, hence, the absurdity of asking about which job one is prepared to do for free. Perhaps, the question means to ask which job would you accept in return a non-montary equivalent of value, in terms perhaps of self-satisfaction or as permission to.make a clearly validated statement of the value you attach to the thing or person(s) for whom you do the job.

The issue of caring for the needs of another is a case in point. Caring for someone with dementia, for instance, often proves to have devastating consequences to the carer because at some point, the reward for the cost in life and spirit to one is so intangible it appears as worth nothing or less. The person cared for may not remember you and may, even abuse you as part of that nonrecognition. You may seek reward in abstracted duty to the idea of an unquestioning loyalty to a marriage or other partnership, but these require imaginative of every possible flexibility in the caring relationship if we are not to be guided by a rigidity of abstract demand that increases risk to one’s life being livable at all, sometimes beyond bearing to well-being and sometimes unto death for the carer.

Yet people who provide care and support for others unsaid are often forced into such work without recompense, a break or even recognition of their time and labour because dependent life is considered a burden on public care systems. a private matter. To labour and spend time with love for another, whether physically, intellectually, emotionally, or all three integrated ( the latter most usual) still costs us. Many carers lose their life in the process of caring or soon after, feeling no chance of regaining what life they feel lost to them in the interim, some with feelings of bitterness of unfairness ( the ‘why me’ moments). And the bitterness costs even when care is as truly selfless as humans can make it seem. But seem is the word.

We work without return of compensatory value of goods both abstract (as thoughts of belonging or feelings of love) and material because that is the condition of living. Religions sometimes see it as the cost of some Original Sin by people that are not ourselves. Whatever, it feels cruel, even done for one’s own benefit. When it is for others, then feelings get complicated.

Working for free, though, in an economic system involves working to produce that which others appropriate regardless as a consequence of their power over you is a different matter. In feudalism, such appropriation was done by a parasitic church and local and national governance by landowners. In capitalism, the appropriation is of surplus value that accrues as profit and as unearned. Do we really value what these supposed superiors do for us, which they claim is to offer us stability and sometimes a good-enough subsistence, while they believe it ‘ sustainable’ [that is, while it still feeds and clothes them in excess].

Socialism is about balance and is thought impossible except in highly over-disciplined forms involving necessary dictatorships that sometimes never wither away, as in Russia or China. And I suppose that is because the principle it asserts is that goods are distributed to each, according to their need, and are resourced by each, according to their relative capacity. Both both need and capacity are considered hard to estimate, and we doubt self-evaluations of them as being potentially unfair, based on our belief that people are selfish as both spenders and workers. In the past, socialised systems have been dependent on huge bureaucratic systems, using inflexible criteria of measurement of those qualities that have been used to measure both.

There are no systems, then, wherein time and labour is needed from us that is in excess of what we need for our own purposes alone. Some of the recompense can not but be in the value we attribute and enjoy in each other’s well-being communally, and hence to the maintenance of others. But that is not an argument against the struggle for socialism. It is a clarion call to recognise that we need each other, and the need of some is non-negotiably greater than our own, just as the capacity to labour for it is less. We have to forget whether or not we will work for nothing and re-evaluate what things have value for us beyond the limits of self. I think I do resent the cost of maintaining the belief that self-interest alone is the best means of maintaining personal freedoms, and, producing and distributing goods and services. But I do understand that change will be resisted by those who benefit from the status quo, which I suppose includes me because I worked in jobs attached to involuntary private pension funds.

Do I have answers? No! Do I think there are no answers? Also, no! I depend on the capacity of those who aim at justice and have the cognitive and emotional resources, combined with strong human values, to find these answers. What is clear is that it will involve love of life and its continua across time and space that is impersonal. Such love needs cognitions, feelings, and actions able to represent it. What is clear is that present systems of accounting for our what we will or will not do for others need something other than a paradigm framed by self-interest. So, of course, we have to say. I will do whatever is in my capacity where it meets a need that otherwise endangers life. If that is for nothing, then maybe I have no value system at all.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx