This is an intriguingly worded question: “What book could you read over and over again?” It’s worth noting that no-one wants to ask about the book you do ‘read over and over again’, just about one of which you could do so and presumably do not do so. In the end it is a question EITHER about what make a book re-readable or what in the reader themselves makes them want to ‘read’ the same book many times. And at the bottom of this lies a more basic question: ‘what is ‘reading’?

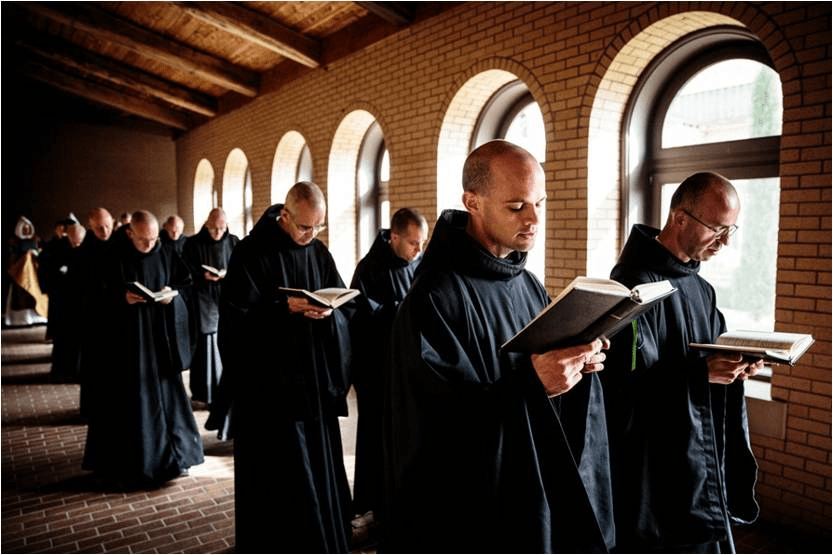

Some books are designated for re-reading. These are often holy texts, such as The Bible or the Quran. But even they are not free of speculation of how and why they should be read. Indeed this idea may be at the base of the very name of the Quran according to Wikipedia:

The word qur’ān appears about 70 times in the Quran itself, assuming various meanings. It is a verbal noun (maṣdar) of the Arabic verb qara’a (قرأ) meaning ‘he read’ or ‘he recited’. The Syriac equivalent is qeryānā (ܩܪܝܢܐ), which refers to ‘scripture reading’ or ‘lesson’. While some Western scholars consider the word to be derived from the Syriac, the majority of Muslim authorities hold the origin of the word is qara’a itself. Regardless, it had become an Arabic term by Muhammad’s lifetime. An important meaning of the word is the ‘act of reciting’, as reflected in an early Quranic passage: “It is for Us to collect it and to recite it (qur’ānahu).”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quran#Etymology_and_meaning

The cusp between the idea of ‘reading’ and ‘reciting’ is vital here, Recitation does not imply a questioning of a text but a repeating of an assumed sameness in the thing recited. Reading has other kinds of potential – ideas that what is received in one reading of a book may different for another reader of the apparently same book, or the same reader at a different time, in a different place or under different experiential circumstances. All of the latter is implicit in the fact that we use the phrase: “my reading of this text is ….”. It is assumed that people read differently for very different reasons. Sometimes, we think of people who read ‘better’ or more accurately than others: that some readers get nearer to some true or intended meaning. Sometimes we think the reasons for different readings lie in a text’s openness to diversity and the potential of a book to mean ‘different things’ at the same time. Sometimes we think of a text as being layered with meanings – cognate, but sometimes contradictory, ones as in Edmund’s Spenser’s allegories or ones shaped by interactions at a deeper less conscious level, stemming from the depth psychology of reader and the text’s own inescapable ambiguities.

The recited text may as well be the chanted or sung text, were the meaning is in the repetition of a basic truth of spiritual being, the text deeply read may be many things in each reading or between ts various readings. The Bible and the Quran are thought of being meant to be read many times, but not necessarily (although sometimes this is the case – hence the need to guard in text-based religions against apostasy and heresy) differently as a result of each reading. In secular terms this is repeated when people read a book again or again to recontact the beauty or unchanging truth of a book in meaning, style or reassuring familiarity.

But we know that writers read all the time and have to do this in order to write. They read not just written or printed words but people or events. In reading, they do not just just listen to these primary sources of their own writing but interpret them, use them as means of answering questions that they continually ask of life. Today I came across a review of a novel not out yet by a writer I read whenever he writes again Sunjeev Sahota (for a review on his last novel The China Room see my blog at this link). His next novel is set in Chesterfield and isn’t out yet. It is called The Spoiled Heart.

I haven’t read it, but today came across this description (with citations) of a moment when the protagonist, a writer recontacts his ‘homies’ in Chesterfield:

“[We] would shake hands homie-style, as we always do, honouring with irony the provincial boys we once were, and would forever be,” he writes. “[Olak would] introduce me [to friends], and I’d chart them recalibrating their idea of me. There would be wariness, perhaps because I was an interloper in the group, unknown to them: brown, educated, a writer.” Nayan is full of sneering: “All you do is slag us from your writer’s throne.”

People may think friends who are writers read their supposed familiar ‘homies’ in ways that critique them negatively, ‘slag us from your writer’s throne’, failing to honour the group of which the writer was, and remains at a deeper layer of his personality or memory, merely one: ‘the provincial boys we once were, and would forever be’. But if his readers think that of how they are treated when they become the subjects of his writing, there is no doubt that the writer too feels ‘read’ in the interaction, such that, as he is read he can ‘chart them recalibrating their idea of me’. These readers use writerly techniques in their articulation of the past and present being – the ‘irony’ about them, that is written in them and ‘honours’ them, is as much by a self-reflection of them as the writer’s reflection on them. Nevertheless it is HIS ironic take on them they fear. They do not see that the writer feels great circumspection about being read and recalibrated by them.

Writers inevitably produce, without needing to write autobiographically, from and of themselves. When their writing is read, we read them as much as about their subject-matter. They are vulnerable to our eyes and the values that lie behind them and which produce readings of them, they do not always want in the open, or feel ambivalent enough to want to show without telling. Modern readers re-read an author in ways that may feel like the knife of Apollo applied to the skin of Marsyas, peeling off a layer – or several layers – without regard to the writer’s pain. Rereading is a forensic examination the more potentially harmful in living authors.

Image on right from: https://wellcomeimages.org/indexplus/obf_images/bb/10/6caaa6769ccede93bac736c7967c.jpgGallery: https://wellcomeimages.org/indexplus/image/L0020561.htmlWellcome Collection gallery (2018-03-23): https://wellcomecollection.org/works/zdr4ph8y CC-BY-4.0, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35994774

Shakespeare has long been an écorché model (but we apply our scalpels now to unheeding and dead flesh). Holy texts protect themselves from such treatment by refining sometimes how and where they are read and in which languages. Protestantism, in bringing the Bible into the home and study has hence a lot to answer for. Prior to that holy text demanded liturgical not critical attention, and had approved readers appointed for their transmission as text or oral passage, who decide what is in the text (canonical to it) and how, even physically, it may be read – in religions demanding for instance an imposed chanted rhythm in the text that MAY be alien to its written language.

Universities tried to do the same with literary text. In Oxford, only authors who were dead and assured a place in the canon (from authors of past generations only) were once allowed to be read, and the way they were read was policed by values not the writer’s own in many cases. This assured some were reread and others were not. But the chosen authors were often stiffened up with authorised readings too often, others edited in ways akin to bowdlerization or even censorship (the old Clarendon texts of Spenser’s The Faerie Queene were even bowdlerised to miss out the references to ‘lily paps’). It is a practice that is more subtle now and perhaps disappearing as universities fail to hold status as authorities. For them, it was once easy to say what SHOULD be re-read over and over again. The canon determined it, and they, in turn, determined the canon. It was a contended area but not contended enough. F.R. Leavis even created a parody version of it. There were only four novelists in his The Great Tradition, and even whole sections of their novels were considered below the standard (the Jewish parts of George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda, for instance). Milton was without value except for an empty sonorous music in Leavis’ Revaluation. Tennyson had less claim than Milton. But what remained demanded re-reading, even Scrutiny, which is the name of the journal the Leavisites invented to do the dirty.

There are many, many novels and poems and plays I want to re-read. I have been meaning to do so with some for literally YEARS, but I remain curious about writing and the new things done with it. If Sunjeev Sahota has another novel due, I have to read it. Sometimes, I have to reread too in order to rethink how I relate to a book. I always reread plays I go to see. The results startle me, Books change with my interests, but I think what I see in a re-reading has always been there (see the blog on the Henry IV plays, for instance, at this link). Re-reading even books like Midnight Cowboy revealed new things that were partly in me. But sometimes what is IN YOU is the only way of accessing what otherwise gets unnoticed in someone’s writing.

There is I think very little that excludes a text for re-reading, although some writing is so lazy it bores me. I have always thought that of people who are venerated like Stephen King and J K Rowling (about the latter of whom A.S. Byatt was just correct), though the former is not a hateful person like the latter.

With all my love

Steven xxxxxxx