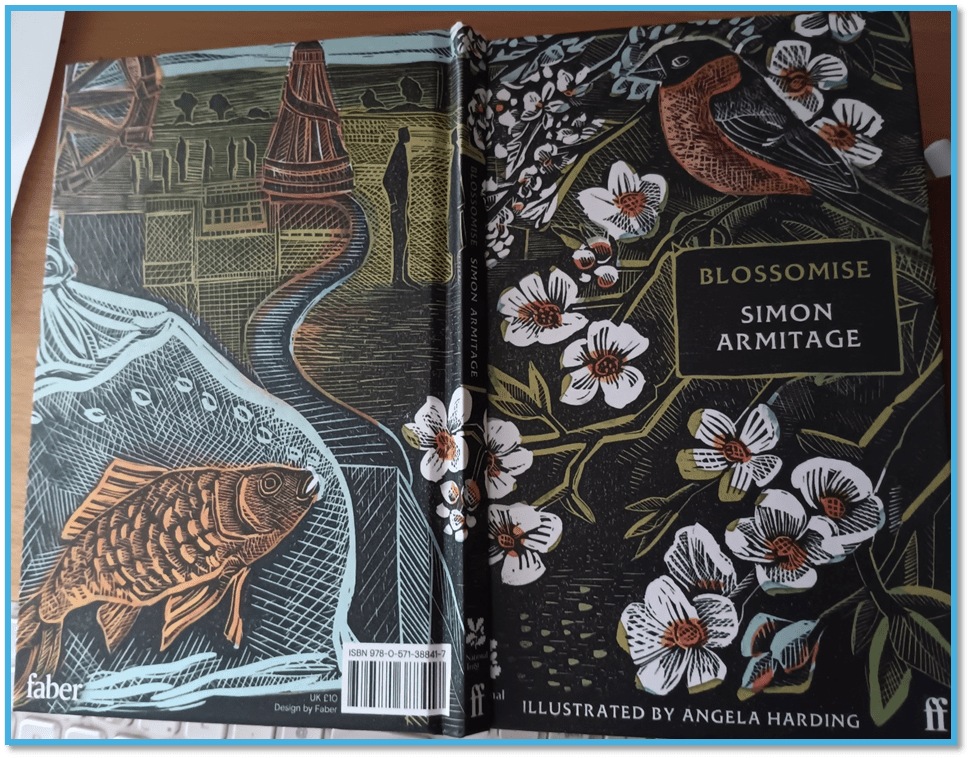

I have no standing in any community I suppose. I am the worst for it. What is it that prompts people to write poetry or to call themselves poets? Is that fervour for community improvement? Simon Armitage’s latest poetry ‘project’ in community politics is published in his 2024 volume Blossomise. I began to be concerned about that word ‘project’, though and I suppose this very question is asking what my ‘project’ is for community. So I will answer very indirectly by showing what Simon Armitage as Poet Laureate seems to be doing. I express my doubts somewhat silently about whether this is the right response.

Is a project that involves the writing of poems defined by the usual prompts to poetry, or what these are stereotypically thought to be? Within these stereotype prompts is ‘nature’ although talk of nature sometimes addresses socio-political and other systems and/or processes, think of Wordsworth for instance or Shelley on a different political register. In this blog, I try to decide if there is such a thing as project-poetry, and why that question matters. Armitage defines the purpose of the Blossomise ‘project’ in part like this: ‘… poetry must speak up for nature when it cannot speak up for itself. These impulses were at the heart of this project; to give definition and dignity to a crucial aspect of the ecosystem, and to give meaning and protection to this yearly extravaganza’.[1]

Since becoming Poet Laureate, Simon Armitage has launched many projects in his name and in that role that have involved many other national institutions, formal and informal. Blossomise is created with the National Trust. Armitage compares its motivation to other projects like tree-planting programmes designed to reintroduce endangered species of tree. The connecting idea he tells us in the introduction to the book Blossomise is that blossom is a sign of the renewal and propagation of natural species of flora. Such ideas have always been linked to socio-political ideas, ones especially contentious when the notion of fertility and reproduction are invoked. In the introduction, Armitage calls for the promotion of blossoming trees in a context where the sites of such trees are in decline. He wants to do so to address the possible consequences of such decline on ‘plants, insects, and animals dependent on them for food, habitat and fertilisation’. That the word ‘fertilisation’ comes at the end of this sentence is no accident. Later, he links the protection of natural environments to display of a process which is linked ideologically to a belief in ‘nature’s capacity for survival and the seasonal processes by which nearly all flora and fauna regenerate or reproduce’.

In modern poetry, this recall to ‘nature’ as a reminder of what matters and is significant has a particularly ideological pull that is not solely about green politics. It touches on core beliefs about how lives interconnect across types and species of flora and fauna. It looks for some connection that is in the end translated between different domains, not only of life-forms, but of the metaphysical underpinning of life as a word applied to flowers and animals, including human animals. As the words of a human being to other such animals, it also invokes a particular framework of human psychology (individual and social), in which reproduction is writ large.

It particularly concerns me when an ‘Author’s Note’ sees the outcome of his poetry-project in birthing social rituals: ‘the hope that customs or rituals might develop around’ poems and songs in, for instance: ‘private contemplation, community activities, formal or informal festivities, or even some kind of wassailing ceremony’. The proximity of ritual to psychosocially binding ideologies seems to be invoked here, and when it is invoked, it does not always promise for inclusiveness, especially when linked to ideas of biological reproduction. Shades of The Wicker Man intervene, including its retrograde politics, whether intended or not.

In the end I suspect though, that the prose is weightier and more portentous than the intention, which is to promote certain niche jazz music festivals centred on Armitage’s band, LYR (there is a review of one such earlier project at this link where the connection of art to communal politics was engineered through the evolving art forms that thrived in dying industries and coal-mine communities, whose politics were not as reducible to a notion of what is ‘natural’. Nevertheless project poetry is inalienably problematic ideologically and politically, as easy to tie to the politics of the right as to the left, and nowhere more so that in the theme of ‘natural reproduction’, for perhaps that’s what is meant by ‘blossomising’.

Another issue however in the concept of a project is that it ties the notion of the poet to that of the bourgeois professional, a tendency that Armitage promotes in his prose about poetry – the notion of a poet and songster tied to the development of their craft, as an exclusive definition of the poetic task. This is very much art as tied to the Greek term, τέχνη and the medieval craft guilds, boundaried by acceptance of a learned skill, perfected through apprenticeship to mastery (see my blog on his prose about poetry as profession at this link). Hence, we expect from these poems the kind of concern with craft that has come to define a rather exclusive club of poets. This is, I think, what makes him differ from a truly committed poetry of inclusion such as that of Lemn Sissay, his contemporary. And it raises suspicions too about the nature of some of Armitage’s poetry as representing some exclusively and ritually defined absorption in its craft and technique that sometimes overshadows any concern with the human subject-matter and defines it through an imposed idea of the artist’s eccentric constructions of what he means by community.

Take the ritual aspects of his poem The Spectators, which starts with ‘Super-excited kids’ bringing parents into a social festivity celebratory of the display of Spring blossom that recalls ‘carnival’ in a rather ‘timeless’ fashion, that blends languages and scenes from the popular theatrical and artistic traditions played in interiors and exteriors across history. But there is no necessity that spring traditions can outlast the decay of ‘blossom sites’ (as the super-professional project worker describes his venues for the Blossomise project touring Britain for the National Trust with LYR, he is describing the cyclical onset of winter of winter, as conventional with lyric poetry, but also pointing to a possible and final loss of the meaning of spring renewal when the ‘rust set in’, with the ‘stark bareness of worlds to come’ (a world robbed of trees and an ancient ritual reproductive ideology).[2] Some short haiku poems pull people and reproduction together in an analogy of an old-fashioned communal commerce (‘market day on Plum Street’).[3]

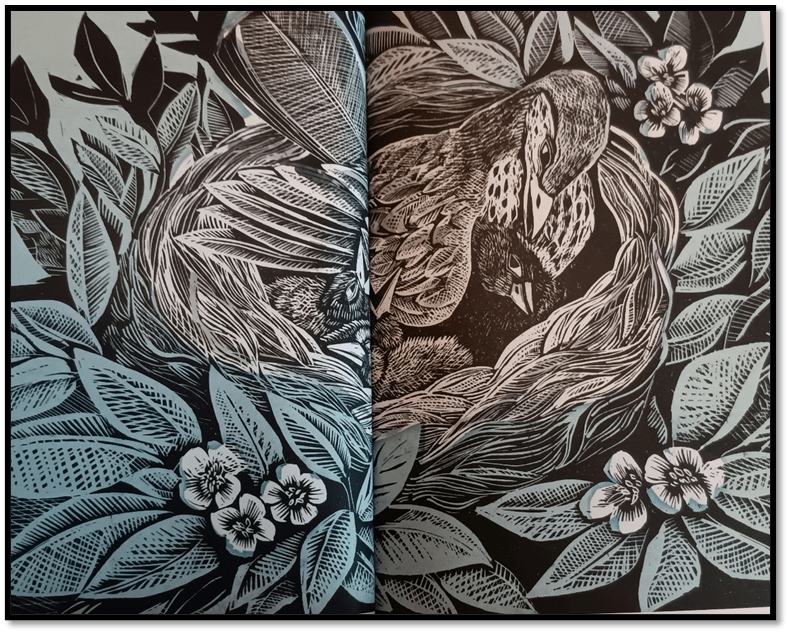

Some of the woodcuts illustrations too seem to celebrate a rather oldie-worldie sentimental view of loving reproduction that valorise family in a false manner, as in this of mother duck and ducklings nesting over blossom.

Folk Song speaks of human fairs that take up space and displace natural profusion and colour so that the latter take on the ‘unfolsky’ image of poverty, the mean-spiritedness of a world without charity and colourlessness:

The woods beyond were sparse and spare,

the branches empty-handed, bare,

no glint of blossom anywhere.

Against this is the promise of profuse reproduction if e let trees breathe in space: ‘as blossom blossomed everywhere / and everywhere and everywhere’.[4] In Fluffy Dice revenge is taken on a working-class man taking on ‘James Hunt’ pretensions (hence the fluffy dice in his care) and the cherry stone he spits out at Tunnel End at Marsden (see below) becomes a tree around which his car is wrapped and which turn him and his cabriolet to ‘compost’. In fact we do not know if he dies but the thought is almost a hope regarding ‘Hunt the Shunt’.[5]

The eastern end of the Standege Canal Tunnel and Tunnel End Cottages, Marsden, West Yorkshire. For more information see the Wikipedia article By Chris Wood, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1539388

Even my favourite poem Plum Tree Among the Skyscrapers has a level of political allegory I rather dislike with a lone urban plum—tree personified as a ‘down-and-out’ lady on the margins of bourgeois society ‘dwarfed by money / and fancy talk’, who dresses to attract with scent, powder and lip-gloss. It’s all rather a tawdry Mistress Quickly like celebration of sexual women ‘fizzing / with light and colour’ and ‘here to stay’. A clearer demonstration of that the status quo is okay could not be found. But it is an accomplished witty (in the seventeenth-century sense) poem: ‘plum in the middle’. The middle way is here to stay it seems.[6]

Poems alone can save us, for the blossom on project-poem tours will have , as in the poem Profusion: ‘budded and bloomed, …./ in July again / in December, …’.[7] The point is that poetry restores cyclical regenerative time not the blank serial leading up to decay alone, as a poem like The Seasons insists.[8] It naturalises the professional ecologist who only audits hedgerows so his ‘wild thoughts’ take over in The Plymouth Pear.[9] My least favourite, though it’s clever and witty poem, is Blossom: CV, playing games with the idea of professions and their diverse commitments to blossom again, that ought to have included poets. Instead it includes: a pavement artist, fruit farmer, measures of the weather, mountaineer, magician, a ballet dancer, a dictionary and the ‘homeless’:

Rootless and homeless, Blossom

rode and drifted

on thermal currents

as the climate-shifted.[10]

Of course Blossom personified is made rootless by climate change but the overall message is that all could be well with the world. Blossom is resilient, like the plum tree among skyscrapers. There is something of the worst aspects of Pippa Passes by Robert Browning here, though I suspect that was not intended for Armitage is a liberal and a climate activist poet in a limited way. Yet I do feel that the jaunty sway of these poems means ‘God’s in His Heaven / All’s right with the World’. This cast of characters in Armitage’s world is in the end a cosy and stereotyped one, dreamed up in a Yorkshire armchair.

Maybe we have had enough of ‘project-poetry’. Let’s get back to commitment and the engaged. I’m with Lemn Sissay and the democracy and modernity of poetry. My Community has to be at least notionally inclusive

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Simon Armitage with Angela Harding (illustrator) (2024: viii) Blossomise London, Faber & Faber with The National Trust. vii.ff..

[2] Ibid: 5

[3] Ibid: 7

[4] Ibid: 20f.

[5] Ibis: 33 – 35

[6] Ibid: 25 – 27.

[7] Ibid: 40f,

[8] Ibid: 50f.

[9] ibid: 46f.

[10] Ibid: 10f.