Write a letter to your 100-year-old self.

Dear illusion,

I do not (indeed I can not) know the entity to whom I am writing. You are an idea in my head evoked by some request to imagine you. As I read colleagues attempting the same task, they seem confident that the person they imagine is on a continuum between themselves, now tapping their keyboards, and a person they will become; an imagined senior self. Some acknowledge that the person may never exist, at least in a physical and animated body.

But I think I do not know you, not because you may be nothing by then that is more than ash and dust, and even then indistinguishable from other coarse materials of the earth into to which that body is mixed. I think I do not know you because I don’t believe that ‘self’ truly has other than an illusory permanence or even continuity. Whether you exist in an intelligible form has long been debated by minds greater than mine, starting with a pre-Platonic analogy based on the fact that ‘I cannot step in the same river twice’. Heraclitus’ phrase as quoted by Plato can be posed in terms too of whether the second step in the river is actually a step taken by the same person for every thing in his view metamorphoses in its flow and fluid dance onward in and through time, including selves, not only running water in a riverbed.

In psychological terms, I think I am with those who think everything we call ‘self,’ whether as a ‘ bundle’ of attributes as with Hume, or a core identity or ‘soul’, as with the wishful and spiritualised thinking of others, passes eventually piecemeal if not by some cataclysmic event necessarily like severe brain damage. They are dubbed ‘non-self’ thinkers.

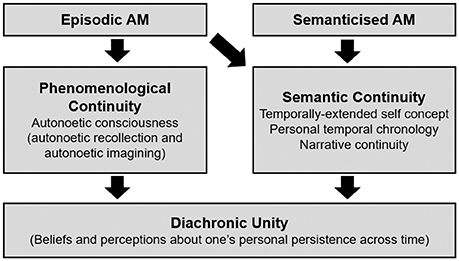

Psychological continuity

In psychology, personal continuity, also called personal persistence or self-continuity, is the uninterrupted connection concerning a particular person of their private life and personality. Personal continuity is the union affecting the facets arising from personality in order to avoid discontinuities from one moment of time to another time.

The debate is summarised in Wikipedia in a coherent enough form:

Wider philosophical distinctions in self-persistence or self-continuity.

In briefer terms, you in your august and venerable age are not a facet of my ‘personal persistence’. I have no uninterrupted connection with you. Indeed, I may have no connection with you at all, as much as this conflicts with the constructions of symbolic logic that we call common sense. To commune with you is like a communion with art: for like art, you in all your illusion of charisma can guide me to something otherwise unthinkable in my present bounded consciousness of existence. It won’t necessarily be a transcendental super-reality or dark sur-reality to which you lead me.

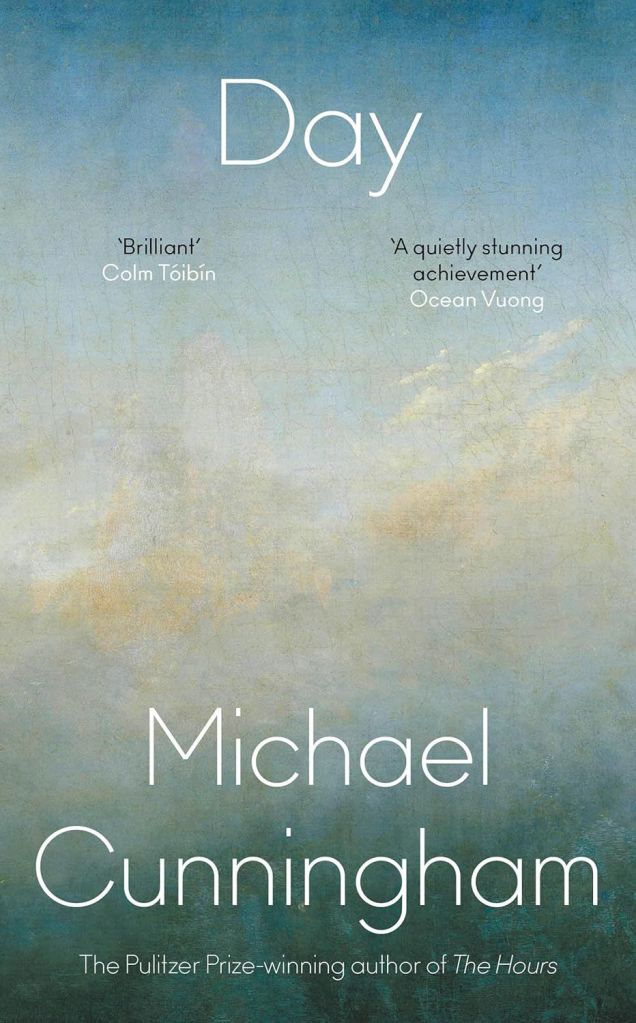

It is rather a moment where what we call creation/preservation and destruction are no longer fearsome. Michael Cunningham has recently put thoughts like that into the head of his character Isabel, locked during a COVID lockdown into a cell of loveless marriage with her husband Dan, who truly only loves her brother, Robbie, as does she (a blog to come later). Here, she communes with Brahms’ Requiem as if with time itself: past, present, and future.

She is free to conceive a celebration of mortality itself, death as a beginning as well as an end, the cracking open of a glory that defies description but, when it reveals itself, may not be the cherubim and seraphim of the official glory Isabel was asked to aspire to as a girl, the painted clouds and winged child on the walls of our Lady of Fatima. This is glory of another sort, a depthless luminous darkness or the wheel of a galaxy or a fire that cleanses as it burns everything away.

Michael Cunningham ‘Day ‘(2024) page 154.

So I think of a 100 year-old person defined by their relationship to others in their grasp of time, such as it is then to them, which may or may not contain a memorial trace of me at 69, and /or me also at 29, or 6 and 9, each of those persons looking to a future it cannot know, and which contingency may cut short.

I think of those thousands of children in Gaza who did not know they would not reach 20, sacrificed to an idea of national identity of which their consciousness is being in part formed by others, by both a loving community as they saw it but wrested from them by violence and the violent aggression of others set violently against that community. Such are the extreme contingencies of imaginable life.

If death or dementia are included in these contingencies, mortality is just one contingent fact amongst others. If there is hope, it has to lie in the possibility that in those thirty years or so, there will be beginnings of something better than the possibilities so prominent now. Those include the insane pursuit of growth that will kill the planet and create only mass extinction. They include also a self-serving belief that self – interest is a good enough guide for a powerful few who mainly control events in their destiny whilst the others wait on the excrement the few enjoy to trickle down on them.

So in your imagined place and time, O my centarian, reflect the West Wind in Shelley’s imagination; preserver and destroyer both, at home with both the contingencies of life and of death, what needs to pass away and what last because it sustains continuing life for more than one poor sickly life-form or its sickly species. But one that must hold the life of innocents sacred as no-one in British political life does in Great Britain now, holding those lives equivalent to fewer killed earlier by the ‘other side’, or to the meaning of revenge.

With love

Steven xxxx

One thought on “O, my centarian, I would like you to be a model of a better self than I am.”