In Jack Thorne’s script from The Motive and The Cue, the character named as the film actor Hume Cronyn, the husband of Jessica Tandy, says when he is reminded of the fact that his wife is better known than him, says: ‘Darling, better to touch the stars than never to know them at all’.[1] This blog is a preparation for seeing the National theatre screening of The Motive and the Cue at the Gala cinema on the 21st February 2024.

At first read, I may have missed the statement delivered by the character based on Hume Cronyn and given his name in this play that I use in my title. Even though an elder, Cronyn was not of my era, or at least that part of it that was conscious of film stars and their glamorous lives, which often played off between the fictions they enacted together in films, or before the glare of the press and in some lesser known ways, to those outside the relatively few that knew them in the flesh. Yet the star system in Hollywood was a means in raw times of creating a pantheon of icons representing some kind of greatness or transcendence, few people touched in reality but yearned to know and to identify with. Most of those stars are now nearly forgotten in the present moment by most, who would not have been born in their heyday, and no longer feel like people we aspire to be like even for those who did know them, and this is the case of the ensemble characters of The Motive and The Cue.

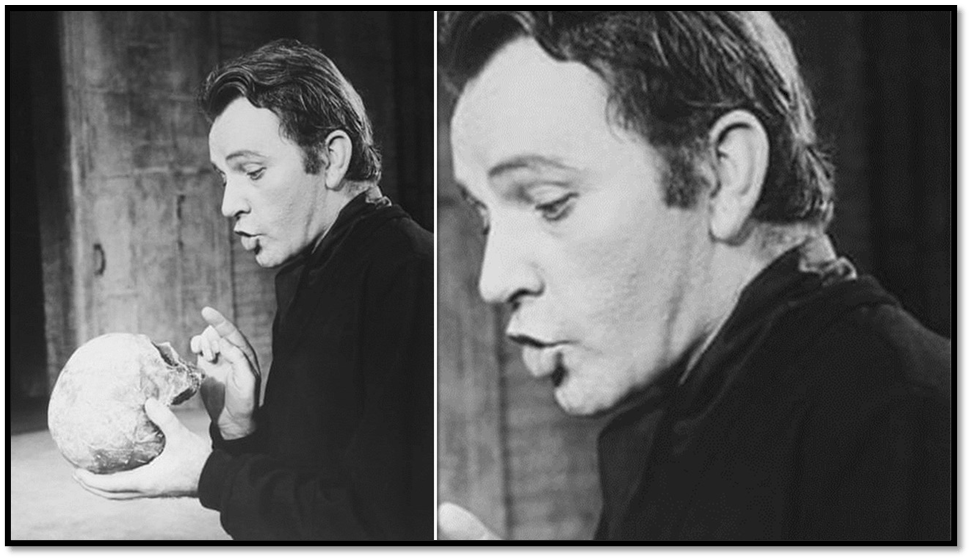

That cast plays another ensemble of actors who are ‘iconic, figures that lots of people have a history with’ as Jack Thorne, the play’s author described them.[2] In this play though modernity probably only at a pinch recognises the enacted characters based on a ‘truth’ of sorts, Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, with a lesser number remembering John Gielgud, for many reasons that we pursue later. How many remember Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy, though they were once a well-known and well-gossiped-about couple, is a moot point. In the play Cronyn’s line in my title is delivered by Cronyn after taunting by other actors of the same penumbra, like Eileen Herlie. Herlie is the actor who is Gertrude in this play’s recreation of rehearsals of Hamlet, although afficionados will know she also played that role in Olivier’s film of Hamlet, a fact that must have rankled with Gielgud. That despised film is discussed between Richard Burton and Gielgud in Tborne’s script. Taylor in the play refers to her however, in lieu of introduction in the Burton-Taylor hotel-room gathering, as ‘you must be the great Eileen Herlie’, with the following ‘playful’ exchanges:

HERLIE: Enchanted

CRONYN: Not sure ‘great’ is the correct adjective.

HERLIE: Fine words from Mister Jessica Tandy.

CRONYN: Darling, better to touch the stars than never to know them at all –

HERLIE: I know you love me, Cronyn.[3]

Taylor interrupts this banter with a ‘you must be –‘, to Linda Marsh. The entire context is of a semi-comic reference between ‘stars’ who reference each other’s relative ‘known-ness’ (in their own right rather than as spouse or partner of someone) which edges on what used to be called ‘bitchy’ of both men and women. Hence Cronyn’s remark is sour. It reminds Herlie that though he is attached by intimate touch to Tandy, a far greater ‘star’ than he, he is at least someone who truly ‘knows’ her unlike Herlie. All very acid bravura hiding beneath ‘wit’ but entirely conscious of the game Taylor is playing – reminding bit actors that are nobodies compared to her and Burton by most measures. But, be that as it may it introduces an important theme of the play, which asks: ‘What is to know greatness, or better to TOUCH it, for ‘touching the stars’ is also a cliché for aspiring to something transcendent. And, in the end, this is the justification of this play. But for those thought of being the untouchable ‘great’ being touched as a person in the flesh is also a kind of aspiration, that tries to exclude the fact that touch (especially sexualised touch) is used as a means of knowing someone, one otherwise would not. But of this, more later.

But so much for introduction. Anyone who reads these blogs for my own learning will know I prefer to read and think about a play before I attend it. The best method for me to both read and think about a drama is to write – and the blogs really are always an aid to my reflections on the plays I am to see before I see them, and after. I am not sure whether this is the best means of enjoying theatre but I think it may be the only one now that works for me, particularly where the story of a play like this one, based on a famous Broadway production of Hamlet in 1964, directed by John Gielgud and starring Richard Burton already holds few surprises as a STORY.

Reading it does prompt some wondering why this seemed an appropriate and significant story to Sam Mendes and Caro Newling for them to transform it into theatrical art, with Mendes in production. Roslyn Sulcas of The New York Times heard from Newling that the ‘motive’ for the play’s creation were thoughts about ‘why theater (sic.) mattered, and what went into making great performances’.[4] Hence when the pair instructed Jack Thorne about the script they wanted the idea of both an ensemble of actors mainly known for more modern media appearance, and one actor amongst them dubbed an unquestionable ‘star’ of the then cinema should ‘crawl into a hair shirt’ as Gielgud describes the come-down theatre must have been for his star playing Hamlet and the company, forced into what seems to them tiny and insignificant roles.[5] .

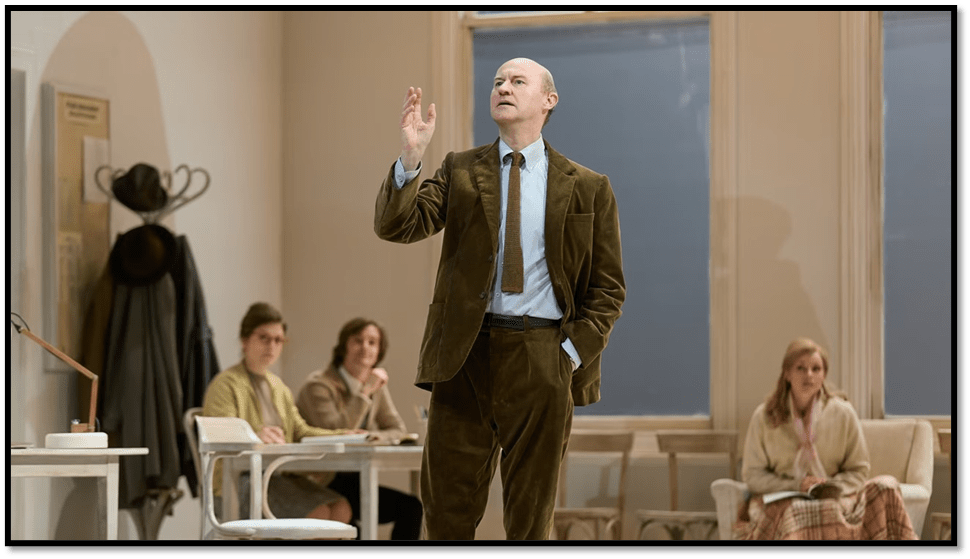

Of course, when The Motive and the Cue was acted in Great Britain where the reputation of Great Britons was at stake, the press could be sniffy. Of course Time Out was enthusiastic, but the reviewer certainly does not see the piece, as reading the play and Jack Thorne about his play suggests to me, as intended for an ensemble in a carefully staged and directed setting – and hence not as theatre as such. Leonie Cooper says:

Though it boasts a cast of 16, The Motive and The Cue is a two-hander writ large, with multi-hyphenate folk singer and screen star Johnny Flynn taking on Burton’s charismatic, boozy bluster and Mark Gatiss launching himself into a condescending but sensitive Gielgud. Under the direction of Sam Mendes, both are sensational.

The representation of this play as focused on two central actors belies the interest of many other interactions and sub-stories in it; all taking both motive and cue from a wish to ‘touch greatness’. That phrase is given to the character, William Redfield, who says:

I thought this was an opportunity to be in something that lives for all time. That’s all I want. To touch that. That greatness.[6]

The statement recalls the wordplay on touching ‘stars’ I spoke of in my introduction. Redfield was based on a real actor of that name who really did originally think his cast role in this Hamlet, as he says earlier in the play, as Guildernstein, was beneath him, but who later wrote enthusiastic letters about the production that, once rediscovered by Mendes, became, or so Sulcas tells us, one of the key cues of the play’s themes. Touching greatness and what that phrase means is very much the base theme of this play, and I entitle this blog with words from another strand of its nuanced appearance. Moreover Jack Thorne himself, writing in The Guardian, makes it clear that his, and Mendes’, intention was to create an ensemble of characters, whose known-ness varies but was once great, as well as the two central ones:

Figures that are iconic, figures that lots of people have a history with, either in person or in passion’.

How do you do justice to these incredible figures? How do you feel able to do justice to them? Particularly in a single evening. These are questions I’ve really struggled with.[7]

Cooper also suggests that the play represents a kind of impersonation of the two canonical acting personalities she see as the ‘stars’ in this play and as the characters they play in an era where the ‘star’ system really mattered to film studios. She says nothing however about the buried but ambivalent homophobia of the interaction of the two, which seems to me central. I can only assert this as a reflection from my own reading because I see this point made, unfortunately, nowhere else. Cooper’s review moreover rather belies its opening gambit that: ‘A play about rehearsals for a play, Jack Thorne’s The Motive and The Cue was already deeply meta, but this transfer to the West End doubles down on such self-referential swagger’.[8] Cooper misses a trick even in this isolated reference to the theme, for the play is anyway about the directed rehearsals of a play that is meant to be enacted as if it were a late-stage pre-dress rehearsal of Hamlet in which the director Gielgud’s says that Act One Scene 9 is of ‘one of my favourite scene, and frankly, one of my greatest nightmares’ because it is about both how to act and how to speak great words: ‘welcome to the Player King and Player Queen’. How much more ‘meta’ can you get? It is a scene in which Hamlet himself is directing the rehearsal of a play, but not a word about these ‘meta’ themes that define great speech, action, performance and ‘direction’ get taken up by Cooper or other critics, of those I read. In my reading of the play, Elizabeth Taylor come across as a great and buried directorial presence, who knows about ‘motive’ enough to animate a theatrical cue, especially a cue in Richard Burton’s buried private life.

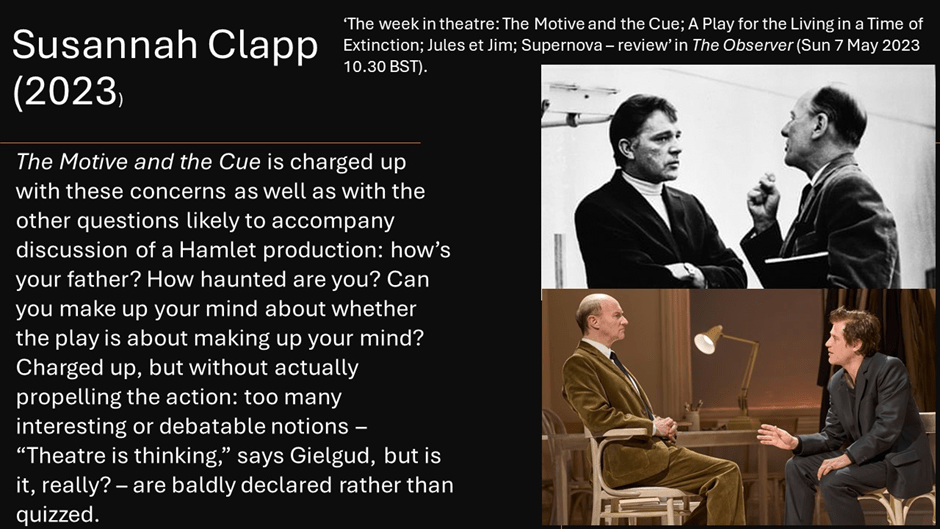

But first for the really bad news, and views, from the British critics. Here is The Guardian’s Arifa Akbar, who on this very theme of the ‘meta’ in the play as described by Cooper says:

But even with its cinematic elements, this is a rather self-regarding homage to theatre. “Together we share the responsibility of what theatre can be,” says Burton. “Theatre is thinking,” says Gielgud, and these observations sound close to mawkish cliches on the mythology and magic of the stage.[9]

To call words clichéd is a cruel thing for a critic to do to a writer, though it is true that Thorne allows his characters themselves to play with cliché, as the phrase ‘touching the stars’ no doubt is. The point is that the ‘mythology and magic’ of the stage is already to some a phrase that is a cliché and is often approximated in ways whose proximity to ‘magic’ is anyway pure pretence at most. But theatrical people still try to find such magic and some succeed.

The point is – how and to what degree theatre achieves magic in a meaningful way. Akbar uses the play’s own words rather wantonly to illustrate her point (a perfect model of bitchiness). The first cited one is from the beginning of the play where its entire context, as spoken by Burton is ironic. He uses cliché, that is, on purpose, propounding a dream in which I think we have to believe (but let’s see how Johnny Flynn plays it) that he believes but which he defends himself with over-the-top statement and humour:

We are stripping back the stage, so he can show your worth. …/ Such an approach takes sympathy and faith. That is, we will make a new Hamlet for our time, held on our shoulders. Together, we share the responsibility for what theatre Can be ; ….[10]

It is meant to be all defensive irony, that will depend on how well Flynn can capture the ambiguity of a real desire and a malignant doubt of its reality. Meanwhile, Akbar feels only in it a poor dramatist’s ‘mawkish cliché’, but is that fair – how else do you represent that cliché can be a driver to action if the belief underlying words is complicated. Sympathy and faith do matter after all, it is how we get at them. The second quotation is by Gielgud at the near-end of the play and we know Mark Gatiss will do justice to something that is more than cliché. He, for the first time (directed by Taylor) realises that there are real depths of discovery possible in the interaction of actor, character, and audience:

That relationship between the audience and the stage – that moment of conversation – theatre is thinking – pure thought – collective imagination yes, but also just – I don’t think there is any other art form in the world where minds meet so beautifully. One thousand people sat together, in communion with what’s in front of them.[11]

Call me ‘mawkish’ but that, well delivered (in all its search for words to refresh cliché into perception of the dynamic beauty of ritual communion) feels like a strong lyrical force of words to me. And if played well (that we need to see) the dynamic of this change in tone of the play from the one speech at the beginning to the otherness the end (given Akbar still feels they are indistinguishable) does illustrate the ‘magic and mythology of the stage’. For Akbar is not alone in her doubts about it all. See Susannah Clapp, for instance, from The Observer in my collage below:

The point is in the acting then. All I can say is – let’s see. But one thing stands out in Akbar’s summary that certainly makes me question her view of what acting is. She refers to Tuppence Middleton’s portrayal of Elizabeth Taylor as follows in ways that seem, well, – ‘bitchy’: ‘Middleton plays the part too lightly, rather like a turn in a TV sitcom, emanating none of the smouldering charisma of her real-life counterpart’. Really! What we see we see, but as I go on to say ‘smouldering charisma’ is a very reductive view of the potential of a great female actor. Middleton, in fact chose to believe that Taylor only playacted the smouldering sex queen – asking for a ‘fuck’ from Burton a great stage where she is wearing no knickers in one scene. Thorne thought highly of her, as he informed Sulcas:

Middleton, who plays Taylor, said, “Elisabeth is the voice of reason, one of the wisest characters in the play.”

“She completely understood Burton’s obsession with conquering Hamlet, and why it was so difficult for him.,” she added. “It was important to me to show she wasn’t this chaotic, floozy character she is sometimes seen as.”

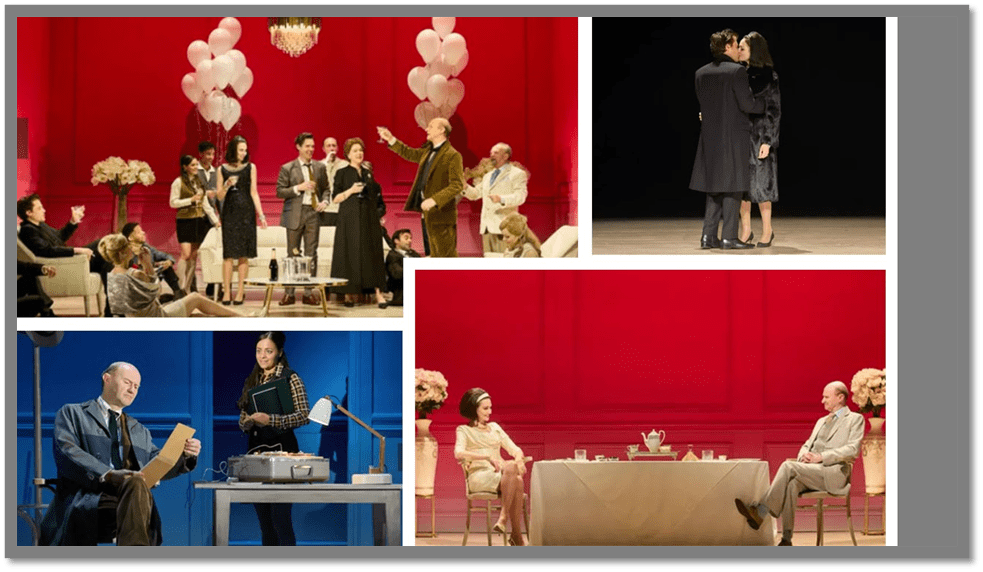

Taylor with Burton at the production

Will I see this in the streamed production? I will not be looking for the ‘chaotic, floozy’ or ‘smouldering charisma’ of a sex-idol as Akbar does, despite herself. From the text, and Thorne’s comments upon it, the lever to the issue is how well the play brings together the elements in which fathers and sons in the play get enacted: those in Hamlet itself, the recounted past lives of Gielgud and Burton with their fathers as told to each other in the play, and in the analogy with paternal authority and direction between young male apprentice and their master that father/son relationships talks about. For Shakespeare this theme (of the ‘Player King’ and his lacklustre son) cements the two plays of Henry IV, hence my excitement at seeing Ian McKellen at 80 capture this in a production I see this month of an amalgam of these plays The Player King, in Manchester (I see it on the 19th just before The Motive and The Cue’s streaming on the 21st).

When Taylor tells Gielgud of the fact that Burton has only ever pretended to like his Welsh miner-father merely because it causes him embarrassment when people see how a lack of fatherly direction has potentially harmed him (his biological father, a miner and an alcoholic, fostered him with his brother), suddenly finds a motive in Hamlet that will cue a great performance from Burton. Thorne’s Gielgud even finds connections with his own family drama. These connections become a real source of that relationship of Hamlet‘s dying player-father, Old Hamlet, a man too weak to rule in his own right except as a ‘Ghost’ and succeeding son, Young Hamlet. It gives Burton a ‘Hamlet’ of his own to play. And in his one moment of giving true ‘direction’ to Burton, Gielgud tells him to play Hamlet in a way that introjects into that character as he plays it and the drama enacted fro it the complexities of his relationship to his own Welsh father, as a man who largely fails his son but gives to that son the task of reparation, or if not reparation, then total destruction for later renewal. Is Clapp right then that none of this deep motivation at all will ‘propel the action’ of the play we see. Are the appropriate cues going to be, as she saw them delivered as ‘baldly declared rather than quizzed’? All this is to see.

In the USA, a better critic, Roslyn Sulcas, believes the author, actors and directors achieved this melding, ending her review quoting them about the moulding of ‘meta’ thoughts about acting and the theatre as ritual, the role in theatre direction of fatherly authority and responsibility to sons, and the importance of the Elizabeth Taylor character and how Tuppence Middleton chooses to play it.

Much of the play is concerned with how to play Hamlet: The breakthrough moment for Burton happens when he can connect his painful past to the character’s motivations. “This is what actors have to do when they strip themselves down to play a role,” Thorne said.

…

“It’s about fathers and sons, classicism and modernity, the clash of these forces,” Thorne said. “But I hope it’s also about why we do what we do, what it feels like and what it costs.”[12]

My own feeling seems not taken up by the reviews however except in passing, surprisingly by Akbar, who says:

Gielgud admits to his envy of Burton and shows his insecurity as a director. We see the fear his homosexuality brings in an era when it was criminalised; a hotel room conversation with a sex worker carries great, subtle power. While Gielgud’s inner complications are slowly but searingly explored, much of what surrounds him feels emotionally sterile.

Using this as a stick to beat the play, production and other actors does not interest me, as much as it does Akbar. For there is vicious used of the homophobia surrounding the aging and increasingly ignored Gielgud, revere only by the great like Derek Jarman, who saw the Prospero father-figure in him in his The Tempest just as Peter Greenaway saw a TV – Dante in Gielgud.

When Burton meets him for the beginning of the production, Thorne shows him full of vigorous envy too of a man who knew more of greatness, I think Burton must have felt, than he hitherto had ever known, with his hammy Mark Anthony behind him. He use homophobic reaction to Gielgud at this introduction: ‘Here is a theatrical gentleman in possession of a conviction. And that conviction is the Actor, …’.[13]

For what everyone in the room would have known, and those of us who value queer history should know, is that Burton is being at his bitchy worst here. He allows the pun to ride, The ‘conviction’ he refers to was Gielgud’s very public one for cottaging. Here is an account of ‘the scandal that almost ended the career of Sir John Gielgud’.

In the autumn of 1953 the newly knighted actor was at the height of his fame and about to direct himself in a prestigious West End production when he was arrested in a public lavatory in Chelsea. Gielgud was charged with ‘persistently importuning men for immoral purposes’, a crime that transgressed the social taboos of the era and threatened to ruin him.

When the actor appeared in the dock, the name on the charge sheet was ‘John Smith’, but a journalist recognised the star of stage and screen, who pleaded guilty and was fined £10. His conviction caused a sensation. The new play, Plague Over England, will suggest that the high-profile case helped to bring the country nearer to making homosexuality legal. It was decriminalised in 1967, freeing millions from the fear of conviction and public disgrace.[14]

Alas, poor Gielgud, I knew him, Horatio.

For me Gielgud is a hero, and Thorne allows him a freely given ‘cuddle’ from a young male sex-worker in this play to show the community in some of its polyamorous complexity where not only sex or references to it matter. Yet Gielgud is truly exposed by Burton. Not that this group would have cared about the existence of a gay conviction, what mattered is that it made Gielgud the more easily a figure of fun rather than authority for them. Yet Cronyn and Redfield still believe in him, so does Herlie despite her experience with Olivier as Hamlet and Director. The issue is that we too often see Gielgud refused the resurrection of ‘his Hamlet’ (especially by Burton who wants to possess his ‘own’ Hamlet) as ‘Old Hamlet’, the part he takes in this production: the ‘Ghost’. If the theatre is a ‘empathy hole’ to catch bears, Gielgud has been caught and robbed of both respect, empathy and faith in his direction-giving.[15] Where everyone talks of a ‘stripped theatre’ before costumes, plenty of other scenes play with nakedness or conditions near that; actors are even compared to ‘strippers’ when Burton belittles theatre in front of Gielgud. People flippantly evoke sex as metaphor, even Gielgud at the beginning, who says to his cast: ‘ You were expecting small talk. Yes. It is nice to flirt a little before we get entirely into bed’.[16] What Gielgud gets in the scene with the rent boy, McHaffie is not sex for he loves ‘another’, his life-partner, but kindness and empathy, a cuddle of full-on touch, which is some kind of true greatness. He cries as McHaffie folds him in: ‘Not self-pity you understand, merely gratitude for your kindness’.[17]

Depends on the whole ensembles acting & their ‘direction’

I agree with Cooper in a way. This is such a meta-play (a play about a play about a play’), that it will stand on the quality of the direction and ensemble acting we see in the streaming. I yearn then to report back later. And much of that skill and grace will be about the acting and reacting to the bits of the Shakespeare play within the play. The stage directions twice refer to an actor ‘becoming the Prince’: once when Gielgud recreates his speech to the Player-King at the end of Act One, Scene 9, and then when Burton wordlessly ‘becomes a Prince’ in the stage directions at the very end of the play.[18] But most of all in will be in that transcendent speech about becoming Hamlet or not, rather than merely killing of the actor-father Gielgud had become for him, for his perfidy to ideal Burton had long imagined: ‘To be or not to be’. [19]

See you after the streaming. Personally I am hoping to ‘touch the stars’ and see and feel greatness.

All my love Steven

xxxxxx

[1] Jack Thorne (2023a:19) The Motive and The Cue London, Nick Hern Books.

[2] Jack Thorne (2023b) ‘The Motive and the Cue depicts John Gielgud’s struggle to direct Richard Burton in Hamlet on Broadway. Its writer describes the task of putting his words into such celebrated mouths’ in The Guardian (Fri 7 Apr 2023 14.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2023/apr/07/jack-thorne-richard-burton-john-gielgud-motive-cue

[3] Jack Thorne 2023a, op.cit: 19

[4] Roslyn Sulcas (2023) ‘What Makes a Great Performance? Backstage Drama, That’s What’ In The New York Times (June 2, 2023) Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/02/theater/the-motive-and-the-cue-national-theater.html

[5] Jack Thorne 2023a, op.cit: 91

[6] Ibid: 86

[7] Jack Thorne (2023b) op.cit.

[8] Leonie Cooper (2023) ‘Johnny Flynn and Mark Gatiss are sensational in the National Theatre’s transferring Richard Burton drama’ in Time Out (Wednesday 20 December 2023) Available in: https://www.timeout.com/london/theatre/the-motive-and-the-cue-review-1

[9] Arifa Akbar (2023) ‘The Motive and the Cue review – Gielgud and Burton battle it out’ in The Guardian (Wed 3 May 2023 09.42 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2023/may/03/the-motive-and-the-cue-review-gatiss-gielgud-mendes-national-theatre-london

[10] Jack Thorne 2023a: 15

[11] Ibid: 91

[12] Roslyn Sulcas op.cit.

[13] Jack Thorne 2023a: 14

[14] Vanessa Thorpe (2008) ‘Curtain rises on Gielgud’s gay scandal’ in The Observer (Sun 10 Feb 2008 00.20 GMT) Available at https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2008/feb/10/theatre.gayrights

[15] Jack Thorne 2023a: 49

[16] Ibid: 11

[17] Ibid: 81

[18] Ibid: 64 & 104 respectively.

[19] See ibid: 82 & 92 respectively.

4 thoughts on “This blog is a preparation for seeing the National theatre screening of ‘The Motive and the Cue’ at the Gala cinema, Durham, on the 21st February 2024.”