The Three Fates: Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos, 1558-59. After Giulio Romano. Artist Giorgio Ghisi. (Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images) Available at: https://historydaily.org/three-fates-greek-mythology

This is a deceptive prompt question. It pretends to be about whether the respondents believes in the ‘existence’ of ‘fate/destiny’, in the same way one might ask whether one BELIEVES in GOD, GOOD or EVIL. These question are called in metaphysics ‘ontological’ questions – questions about whether a thing exists or not. In most cases, it will be answered by bloggers as if it were not a matter of ontology but of epistemology, another branch of metaphysics, dealing with questions about what and how we can KNOW about a thing we believe to exist: in which unsupported or foundational belief may be considered either the only basis of ‘knowing’ such a fact, or a large part of it.

Medieval philosophers could suppose ‘proofs’ of the existence of God, such as those of Duns Scotus. These tend not to invoked, amongst serious thinkers (people who believe in the power of rational thought) after the eighteenth century and belief becomes a standard of assertion of belief in that Being’s existence in its own right. And much the same might be said of Fate, often thought to be the means by which the divine operates and shows itself in the world – predetermining what will come to pass in either the ‘macro’ sense (in say predictions of the Apocalypse) or in a ‘micro’ sense, in pre-determining the course of an individual’s life, regardless of that individual’s attempt to use its own agency to influence the achievement of desired outcomes. These debates fade behind other questions, of the predetermination of personal events or causation of those events by ‘free will’ alone (or a combination of the predetermined and the willed) as the reason driving the unfolding of one’s life. Milton exercised himself with these questions all of his life:

Stephen M. Fallon ‘”To Act or not”: Milton’s Conception of Divine Freedom’ in ‘Journal of the History of Ideas’ [Vol. 49, No. 3 (Jul. – Sep. 1988), pp. 425-449 (25 pages). Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/2709486 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/2709486).

They are messily explained to Adam in Milton’s Paradise Lost by the Archangel but God gives his own explanation later.

I tried to explain the Archangelic version in that earlier blog, citing Book III of Paradise Lost :

…in which God predicts that man will be tempted and will (as is his FATE, the word presupposes) to temptation Fall:

… : so will fall

He and his faithless progeny : whose fault?

Whose but his own ?

Paradise Lost, Book 3 lls. 95ff.

God says these words to his son, without yet revealing the consequences of their narrative to the son’s future role on the cross, that though Man is bound to ‘fall’, that fall is Man’s ‘fault’ (including in that fault both the present human beings in Paradise, Adam and Eve, and ‘their progeny – even those yet unborn) and Man’s ‘fault’ alone.

https://livesteven.com/2021/06/12/so-will-fall-whose-fault-paradise-lost-book-3-1-whence-queer-poetry-reflecting-on-andrew-mcmillan-2021-pandemonium-forgive-misunderstandings-and-any-gaucheness-andre/

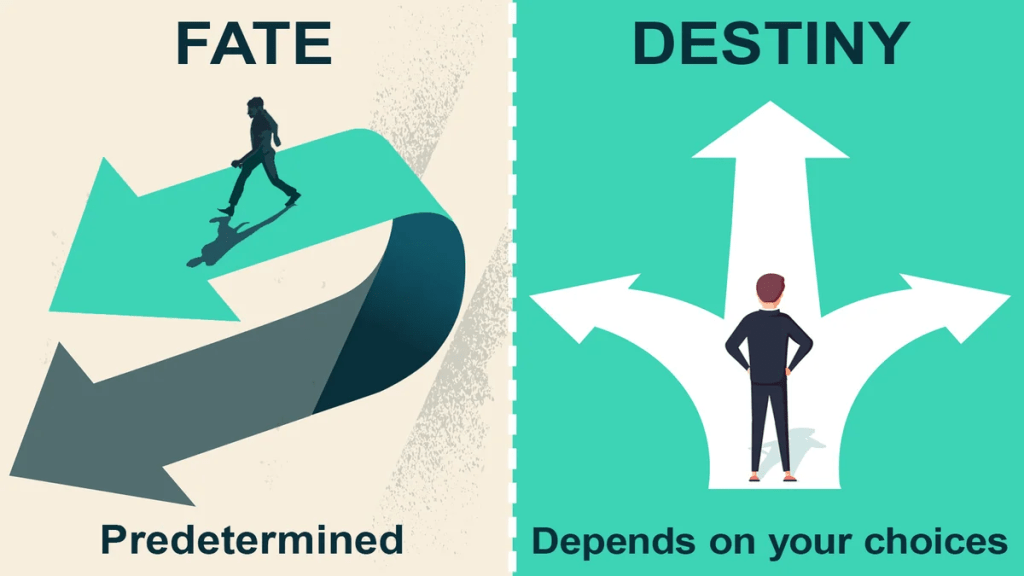

Thus enters into the debate, roughly from the Protestant intellectual revolution of the fifteenth to seventeenth-century but in a more generalised in the late eighteenth century onwards, a distinction between the two words lumped together in our prompt as ‘fate/destiny’. In this thinking, now very prominent (try an internet search), ‘fate’ is different from ‘destiny’. Both predict an outcome but whilst ‘fate’ stresses predetermination, destiny allows a modicum of ‘free will’ that ensures that the FORM our destiny takes depends on the agency of the person’s effective choices. Here is a way of showing that difference graphically – often stated on the internet as if it were a canonical truth, especially by institutions who see their role as that of a counsellor:

Available at: https://www.yourdictionary.com/articles/fate-vs-destiny-meaning-use

So if we split the prompt apart using this distinction between the two names of its subject, fate/destiny, it invites us to debate whether we believe that each individual person or group (maybe a nation as suggested by the Make America Great Again movement [MAGA]) can choose between EITHER parallel (or diverging) destinies OR must follow a path already set out. If this path is not predetermined by God, it could be by the ‘laws of nature’ (a very old-fashioned concept now) or resultant from the consequences of past failure, such as a religious ‘fall’ or even overuse of fossil fuels.

And most bloggers I suppose, for we are all children of our times, will answer this question in terms of how they see themselves in the conundrum. Am I passively fated or destined by external forces (ranging from God to social systems or elements of it – like family experience) or have I made choices that have allowed me to escape or transcend those fated elements by force of my own personal, political, spiritual or even belief-in-self-led choices. We are in the realm of ideas about risk-taking here – wherein people identify themselves with the risks they faced or otherwise – autobiographies about recovery from ‘mental illness’ or ‘addiction’ fit into this paradigm perfectly.

‘I took control’, ‘I realised that you have to believe in yourself’ are all sayings oft heard where the question has turned from one about belief in ‘fate/destiny’ to belief in one’s personal power to overcome adverse circumstances – made by self, others or both together – that make the individual responsible for themselves in effect. The favourite quote is from the motivational analyst, Michael J. Meade, a quotation put in an appropriately sombre but calm background as below: ‘Destiny is purpose seen from the other end of life’.

It is a quotation that solves nothing, though it may in context – I can’t bring myself to read Meade in the original. If ‘destiny is purpose’ that is a phrase that merely repeats what we have looked at before – you enter life with a destiny that will be shaped, whatever the fated elements, by whether you have self-determined your ‘purpose’ or not, and if so, in what direction your purpose tends.

But it does not say quite that. Purpose is not causative in this phrase, though it appears so. We are talking about ‘purpose’ solely as a retrospective interpretation of earlier choices: ‘purpose seen from the other end of life’. That implies that the ‘purpose’ need not have been ‘seen’ when it was applied initially in your life, but will be when you interpret HOW you got from that place to this at the ‘other end of life’. That last phrase is notably ambiguous.

All individuated life has in fact one end – death – though our path to it and its duration is host to influence and choice (but usually choice enabled by an individual’s personal ‘share’ of resources) but this quotation doesn’t necessarily talk about death. Anyway, the idea of purposing one’s death is usually seen as taboo, or, at least, an exotic idea. Rather, it employs the notion of ‘end’ that already means having a ‘purpose’ or ‘goal’: an ‘end that drives one – a teleology). ‘In my beginning is my end’ is a phrase oft quoted that plays with every sense of both words, but it also suggests that purpose is a creation of narrative – that force of story-telling that casts lives into ordered sequences as Aristotle defined them: ‘a beginning, a middle, and an end’.

And if our destiny is merely that retrospective interpretation of what we become, the stories of destiny we actually get to hear will always be those of persons who believe their life to be a success or major achievement. Do we hear of the failures, except in some of the under-rated dramatic monologues of Robert Browning? In Andrea del Sarto, the artist narrator tells of an achievement less than he had wanted because of his passivity and lack of felt control over his world, and his wife, ‘Lucrezia’, who is ever on the lookout for more virile men, as lucre seems to do to men more impoverished than they feel themselves to deserve.

In the twentieth century, the role of destiny is taken over by ideological constructions of the self-made man (and it’s always a man). In the 1950s, the ideology was expressed as a ‘dream’ but used as a tool to sort the valid man from the invalid one. Its best expression is in Arthur Miller’s The Death of A Salesman. Willy Lomax is invalidated by failing to live up to the ‘the American Dream’ and fails as a salesman, a husband, and father, much like Browning’s failed types. DESTINY has become the FATE of the unremarkable and forgotten majority, the many not the few with names and boastful stories to tell, like that of Othello, who thought he had overcome his beginning.

For T. S. Eliot, narratives can’t even restore human destiny even retrospectively because ultimately, though events may seem to lead to a desired end, the things that they produce themselves lose their meaning in the longer duration: ‘in succession’:

In my beginning is my end. In succession

Houses rise and fall, crumble, are extended,

Are removed, destroyed, restored, or in their place

Is an open field, or a factory, or a by-pass.

Old stone to new building, old timber to new fires,

Old fires to ashes, and ashes to the earth

Which is already flesh, fur and faeces,

Bone of man and beast, cornstalk and leaf.

Houses live and die: there is a time for building

And a time for living and for generation

And a time for the wind to break the loosened pane

And to shake the wainscot where the field-mouse trots

And to shake the tattered arras woven with a silent motto.In my beginning is my end. Now the light falls

T. S. Eliot ‘East Coker’ from ‘The Four Quartets’. See: https://genius.com/Ts-eliot-four-quartets-east-coker-annotated

Across the open field, leaving the deep lane

Shuttered with branches, dark in the afternoon,

Where you lean against a bank while a van passes,

And the deep lane insists on the direction

Into the village, in the electric heat

Hypnotised. In a warm haze the sultry light

Is absorbed, not refracted, by grey stone.

The dahlias sleep in the empty silence.

Wait for the early owl.

Eliot was a great fan of cyclical narratives – hence his religion and his view that humanity only had illusions of achievement rather than real achievement, given the nature of successive time. There is an irony that he took the words for the first line of East Coker, quoted above, or so he said, ‘In my end is my beginning’ (and then inverted them) from those fabled to be those of Mary Queen of Scots at her execution, for if her death can be tortured into meaning the beginning of a Stuart destiny in Great Britain, it could equally predict the Stuart prompting of the Civil War and eventually the end of absolute monarchy.

If destiny is just a story, and Eliot thinks it is, the story of the set of stories told in Ecclesiastes in The Old Testament about there being a ‘time for everything’ can only be true in the short term. In the end we have to go back to the beginning of that drear book of wisdom to realise that, in the duration of eternity, we all have to agree that ‘All is vanity’, including the stories we tell to cheer ourselves up about our own significance to others. The main intellectual aim of Ecclesiastes is to establish from the outset that all is indeed human vanity in the eyes of both God and the wise. And that vanity includes the sense of the historic significance of nations and would-be Empires.

However, if I try to address the question prompt as asked, I suppose I would have to say that both fate and destiny are NOT things associated with my ability to ‘believe’ in them. They are instead aspects of the degree of control I have over telling my own story in a way that illustrates them and my desire to tell such stories. People who believe themselves to have failed rarely tell public stories, preferring an auditor more likely to cheer them up. Those people anyway have, as more than likely, accepted criteria for success and failure that are ideological reflection of their society and culture’s core beliefs. Those criteria at this moment, a perfect monument to Blatcherism, are those of competitive self-interest within the ideology of capitalism.

My preference is to accept that survival alone guides success, but by this, I mean not personal survival but an attempt to maintain a set of values beyond the vanities of individuals or self-styled leaders of social opinion. My preference leads of course, to a world of ideals (unpopular things in this pragmatic world). In fact those ideals I would want to maintain are often nuanced enough to yet find evidence of themselves still in social structures and interactions, like those of everyday work and the exercise of power, that are antagonistic, in the final analysis, to those values, as our ‘recent’ POST OFFICE scandal revealed – for it is NOT an isolated incident, just one of the very few where brave representatives of MANY fought back against the institutional FEW designated managers and directors. And our only hope is to DENY the right of a mean and vicious social ideology (that benefits the few, not the many) to be that which has the right and agency to give a final analysis of the conundrum I have spoken about above.

Well, that’s what I think …

With all my love 💓

Steven xxxxx