Part 2 of a two-part blog about Andrew Scott’s achievement in enacting all the multiple personae of Vanya, as aspects of the solitary and solipsistic self, perhaps (or perhaps not). (Part 1 was about preparing myself for the novelties of the Simon Stephens’ text).

Part 2 of this two-part blog about Andrew Scott’s achievement in enacting all the multiple personae of Vanya. In this part 2, I discuss seeing Andrew Scott perform all the roles of this play, as it was intended one actor would, in the streamed version of Simon Stephens (2023) Vanya, at the Durham Gala Theatre at 7 p.m. on Thursday 22 February 2024 (the first national streaming). For Part 1 use this link.

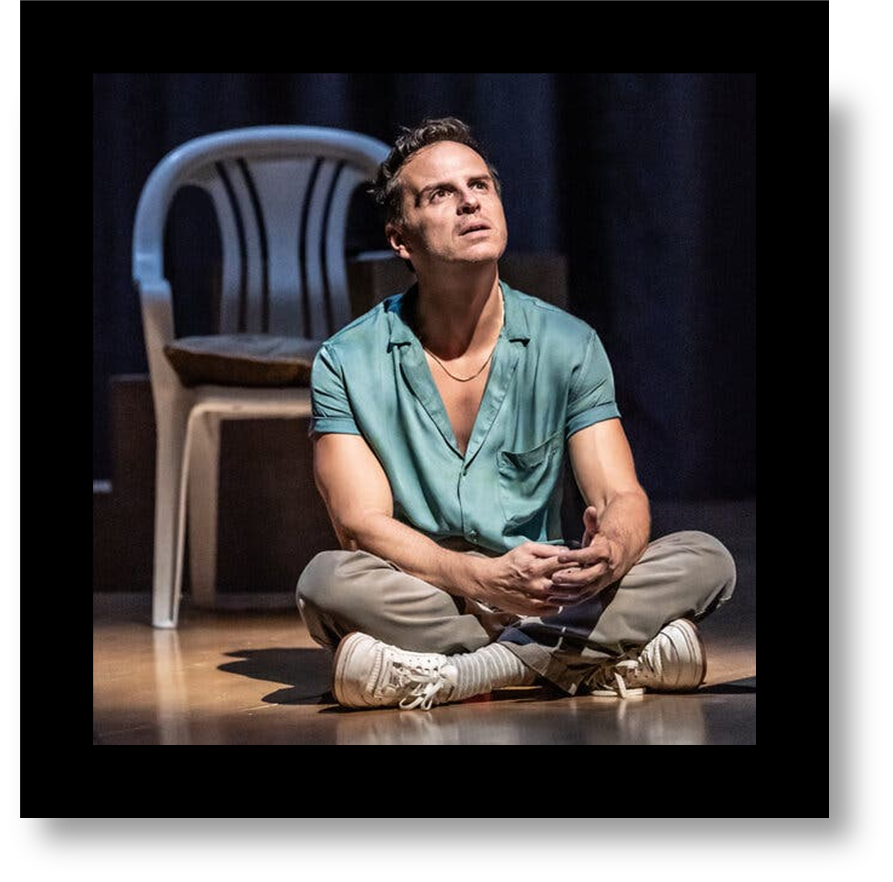

I said I would do a Part Two on this blog and I will but it’s difficult to do justice to what Andrew Scott adds to this play and its themes. This was a stunning evening of a production ideally suited to streaming with its access to close-ups of an actor who acts through every varied moving part of his body, and who cries real tears as Sonia in her final soliloquy as she hugs the leg of the broken Vanya, a comedian and impostor filmmaker manqué himself but now so deflated such that he seems terribly right being represented at the play’s ending as an empty plastic chair at whose foot ‘Sonia’ sits, at one point stroking her arm as if it was (I swear I saw it) her beloved uncle’s leg; the only thing left of her mother apart from the ghost tunes visibly played on a piano.

Of course I read the reviews, and they are a mixed bunch, though they review the stage production seen at The Duke of Yorks Theatre but not in the detail of the streamed version. One feature of some of these reviews is the desire to prove the critic greater than the ‘showman’ to whom Scott gets reduced. Some see only the clowning – gross, fine and funny as it is in, for instance, Michael, the doctor, for instance, as he opens the door of the fridge to ‘cool his ardour’ (and reduce his visible erection – not that we see it) after his one last near-sexual consummation with Helena, against and involving a door – acted so perfectly as if two near naked bodies were contained in Scott’s one flexible repertoire of flesh, bone and muscle, active at each of those muscles in each part of his body. Strangely one of the worst offenders is Houman Barekat in The New York Times, who misses the finesse I try to capture above but which I saw without doubt. He sees in the performance only Scott ‘channeling the tongue-in-cheek demeanor of a clown or pantomime artist’ with that fine scene of mutual seduction reduced in his Barekat mind to ‘the strange, and somewhat dissatisfying, spectacle of a man flirting with himself’. If anything is unedifying it is the USA trying to be more elitist European in its judgements than the ‘old world’ itself. But it is the more so than when it pulls out jokes against queer actors for making his ‘female characters occasionally come off a bit campy’.

But Barekat’s aim runs through other reviewer, many Europeans. The aim is to see the classics of European theatre, like Chekhov’s fine plays, as too large and too monumental for modish, camp and showy actors , too big for their ballet shoes. Obviously Barekat has offended my community and I try to take poor revenge above but it is laughable to see the posturing of critics before idols from the European canon, that are not understood but frozen in the aspic of ‘traditional’ ways of seeing and reading them. It produces judgements like these:

There is, moreover, an emotionally shallow quality to Scott’s onstage presence, a certain glassy inscrutability that suggests he’s a little too steeped in wry self-awareness to comfortably inhabit any other mode, ….

To the shallow all is shallow, except the authorised judgements of time, which must be referenced by Barekat in order to suggest that he sees so much more, and more deeply, in Chekhov of ‘the play’s moral complexity and emotional resonance’ than any theatre geek could do:

The end product is what counts, and in this instance, the play is not well served; if anything, its pathos is diluted. Constraint for its own sake is self-indulgence, and there’s a fine line between a conceit and a mere gimmick.[1]

Surprisingly enough a better critic, Afrika Akbar in The Guardian, peddles much the same view though but with more nuanced, appreciative and delicate balance with regard to what Scott and the production does achieve, saying: ‘ … this really is the Andrew Scott show. Chekhov comes second’. She picks up similar triumphs in Scott as I mention above, including the:

… carefully controlled, thrillingly virtuoso physical performances. He exits as one character and enters as another, excelling in the plate-juggling feat of playing two or more characters in conversation. Where the romances might so easily have felt off-kilter, they reel us in, even though the sex scenes that follow push us back out with the sheer oddness of Scott’s solo enactments.[2]

But there is more than ‘oddness’ here and much more ‘queerness’: there is a sense that the body is really a flexible thing that can be retrained and re-sculpted to shape-shift itself across false binaries like sex/gender, fiction and fact, auto-eroticism and the alterity of mutual embodiment, fact and fiction, truth and lies. And, we can’t escape the main point of the review : that fine actors are lesser than the great plays they choose to see adapted. She doesn’t see camp, more a kind of British light comedy of the ‘saucy’ type, but more cleverly enacted with fine use of theatricality with stage properties:

Each character is given symbolic tics and changes of voice: Helena is a posh woman who twiddles her necklace. Vanya is a rakish type who lopes around in sunglasses. Michael is little short of the “hot doctor” who speaks in occasional double entendres. “You wanted to see my maps?” he says suggestively to Helena in a scene in which he reveals his passion for the environment – and for her.

It is all very entertaining, with lots of sharp comedy (Stephens’ script has some great one-liners) but it renders characters flimsy or broad. Some rise above this such as Sonia, whose pain of unrequited love is played with a smiling vulnerability that is moving.[3]

Well, yes. The doctor is ’carry-on’ leery, but I found that a satisfying thing for it strikes through his Russian model’s real passion for a socio-ecological politics that is more distinctly Chekhov’s than in the other production I look at in Part 1. And what was conveyed was the importance of seeing through the sex/gender rigidities that have frozen in people like Helena and Michael (Yelena and Astrov in Chekhov). And I felt pleased that I knew that the Stanislavski production (subliminally praised as everything and all Chekhov can be) was considered rather heavy-handed by Chekhov (I discuss this briefly in Part 1), who would have preferred more ‘lightness’. And lightness, as I predicted, Scott gives it, in order to point out, all the more, the tragedy perceived as a triumph of noble illusion over reality by Sonia (and he does Sonia so well) or the ‘way of the world’ as seen by the fag-laden Maureen, still bearing the wisdom of a peasant class in Ireland now gone but still insightful of the arrogance of the powerful they have to serve.

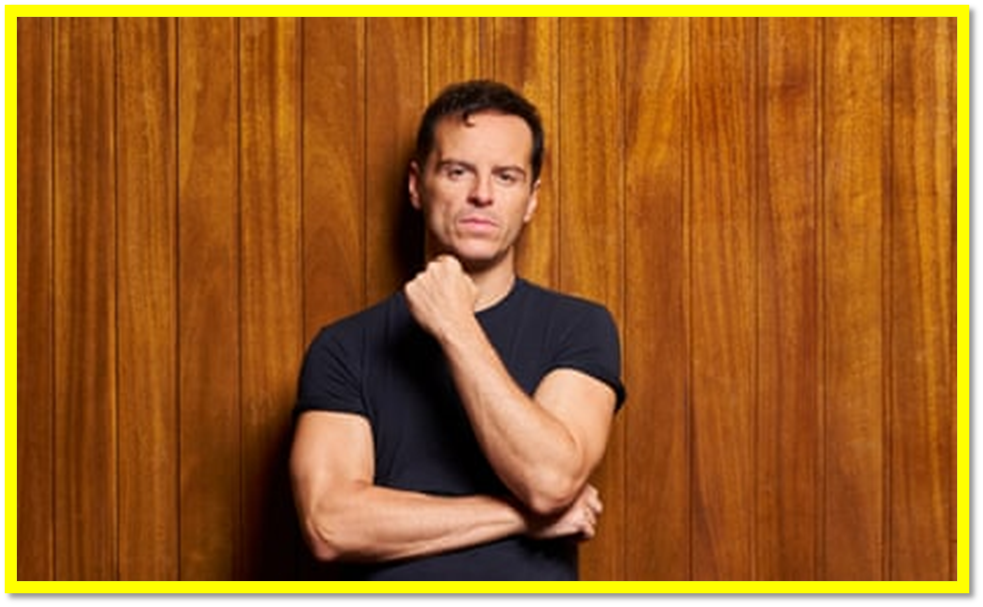

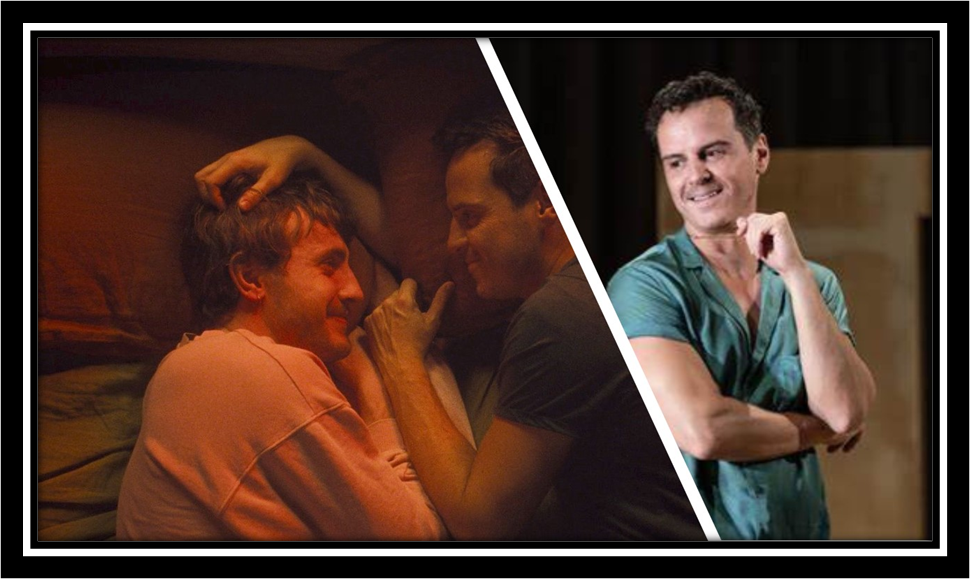

Maureen casts a backward eye on the upper classes and petit bourgeoisie she serves: Andrew Scott. Photograph: Marc Brenner

Chekhov, knew, I guess but I don’t know (who does?), that you needed more ‘lightness’ than Konstantin Stanislavski’s ‘method’ offered. Hence, I am still pleased with my Part 1 collage (see below). Moreover, the only really good reviews that I read got that point about tragi-comedy: like Andrzej Lukowski in Time Out, who says of that very astute opening dialogue between Maureen and Michael, all within Scott’s body: ‘the scene is not hammed up by the production: it simply feels like two people having an intimate conversation’. I so agree. That is ‘lightness’.

Lukowski is right about Scott as Ivan (Vanya) too: ‘assuming the role of the never-quite-grew-up title character, and pulls out a little red plastic box that makes silly electronic noises’. It is his own childlikeness that breaks Vanya but not Sonia, for she can entertain adult delusions without a psychotic version of impostor syndrome.

In role as Ivan (note the plastic noise-box) with part of the fine set (see end of this blog for comment).

I am with Lukowski too here, in these summaries of the actor: ‘not a man hammily flexing between roles but something more profound and complicated, a headlong odyssey into the devastating emotions at the play’s heart’. And even more with him in this about the value in understanding much more what Chekhov might have desired from Stanislavski

As Vanya faces up to losing the estate he sacrificed everything for and Michael confronts the solemn Helena with his feelings for her, it feels much more intense than the average ‘Vanya’, like human emotion almost freed from narrative and shredded down to its purest, basest level.[4]

And, if that were not sufficient authority (it is for me) read the ultra-perceptive Sarah Hemmings in The Financial Times. She is a critic who truly understands how theatre works, taking into account the fact that Scott plays not only all the characters but also the function of a director, engaging the audience by manipulating how the play uses set, properties and lighting, through the fiction of his directorial role, leaving Sam Yates, the true director, unrevealed. And she grasps that all the characters can sometimes lose the boundaries between each other- for what they enact is the vast comedy of embodied humanity, including even the ghost of Sonia’s dead mother Anna, trying to find meaning in what is absurd and meaningless, and cruel:

The characters seem to exist in a kind of limbo, haunting the stage and reliving a memory. It’s as if Scott, by wandering on to the stage, flicking on the lights, firing up the kettle and slipping into the first scene, has summoned up that sultry late summer when a moment of crisis brought them all face to face with themselves. His intimate delivery, together with the easy contemporaneity of Simon Stephens’ adaptation and the makeshift style of Sam Yates’s production, draws us in. We’re working, with Scott, to people this stage with characters, to eavesdrop on their thoughts and invest in them the regrets of our own lives. It’s an approach that celebrates the complicity between writer, actor and audience in creating theatre and that dials up the empathy at the heart of Chekhov’s work.

Now, that is what I call exceptional theatrical and literary criticism, that ends with earned panache about the rightness of not always knowing WHO is speaking out of all the dramatis personae: ‘we see how much they have in common: how much we all have in common. Tremendous’.

And sometimes we need to laud excellence. Excellence boiled down to a single seeming act – about two hours but must have seemed so different to Scott, where one never bores and where emotion is continually reshaped by selective release and inhibition and, yes, sometimes belly-laughs. This is surely genius. Just how much meaning can good acting put into Michael’s hopeless protestations in ‘Act Three’ of being a recovered user of alcohol, in a still alcoholic drawl: ‘There. I’m done. I’m sober. Look. I’ve sobered up. I will stay like this until I die’. Indeed he will – hopelessly locked in unknowing self-multiplicity – like us all perhaps!.

So much for that actor-man who also enacts a kind of self-direction of his inner personae. But he ONLY enacts it: for there is much more to see of the real evidence of others involved as Scott knows too well, as a consummate ensemble performer. The direction MUST have been superlative by Yates. And what of the set, for I have spoken a bit about the inventive properties (my favourites being Ivan’s plastic sound box and Sonia’s tea-towel: “she’s so …”, says Helena speaking of Sonia so wickedly, whilst rubbing her hands mockingly in the same tea-towel. True to form Barekat in The New York Times is sniffy about the set too:

The set, designed by Rosanna Vize, is carefully calibrated to evoke nothing in particular: A laminate desk; a fiberboard door frame; a generic, possibly midcentury, kitchenette. Scott’s attire is likewise neutral (sic.).[5]

Mastery of the art of damning with reductive description, Barekat misses the point here again. The rather makeshift nature of the set is part and parcel of how the play is reduced to its essentials – focal points of living and surviving (the kitchenette where food is a fine bit-player even in Chekhov’s text) and portals through which character roles disappear, metamorphose, meet, get mirrored or sometimes make love or show it in support (as Sonia with her uncle – the sole remnant of the flesh of her mother). Akbar is much more intelligent, aware of how theatre works and of true post-Stanislavskian traditions (in Jerzy Grotowski and so on):

Vize’s set design exposes its workings, with plywood boxes and props scattered around the stage. The back curtain is drawn to reveal a mirror reflecting us, the audience, back at ourselves. This becomes meaningful in a production that requires us to actively build this ostensible rehearsal space into an imaginary world.

In the end, we don’t read Chekhov at all if we keep reproducing the nineteenth century naturalism of the Stanislavski ‘method’ in acting and mise-en-scene. As I said in Part 1, Chekhov himself felt those productions ‘heavy’ (in every sense).

Relationship with audience is essential to modernity of any production today and even the production of Conor McPherson’s version of Uncle Vanya used monologues addressed to the audience in a quite unnaturalistic, in terms of theatre convention, manner. The Stephens adaptation plays games with its audience over the updating of its context to a class of filmmakers rather than the philosophical, literary critical and performance classes in the original text – and deliberately chooses recherché filmmakers for Ivan to identify with (Bresson, Ozu) rather than Uncle Vanya’s well known ones (Schopenhauer and Dostoevsky). The aim is to show the artifice in the lives represented (lives busy always anyway representing something other than itself – so much that what itself actually IS goes unsaid).

And indeed, Chekhov MEANT to satirise certain over-dogmatic traditions in literary theatre in Uncle Vanya anyway allowing Vanya to say to Serebryakov:

All those essays of yours that I struggled to get through, thinking I was stupid because I couldn’t make head nor tail of them, I realise now you’ve been having us on!’

Or in filmic terms as Ivan says to Alexander in Stephens version: ‘My God how I hate your fucking films. … You call yourself an artist? You wouldn’t know art if it shat in your face’.

Paring down to the basics of ‘poor theatre’ is true theatre. Don’t put up with continual stale repetition. There is no need. And if master-class in what embodied enacting was required, why go further than Andrew Scott.

Do see it! – and then see All Of Us Strangers again (for my blog on later see this link).

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Houman Barekat (2023) ‘Review: Andrew Scott Plays Every Part in ‘Vanya.’ Why?’ in The New York Times (Sept. 22, 2023). Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/22/theater/vanya-andrew-scott.html

[2] Arifa Akbar ‘Vanya review – Andrew Scott excels in one-man Chekhov’ in The Guardian (Fri 22 Sep 2023 10.23 BST Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2023/sep/22/vanya-review-duke-of-yorks-theatre-london

[3] Arifa Akbar (2023) ‘Vanya review – Andrew Scott excels in one-man Chekhov’ in The Guardian (Fri 22 Sep 2023 10.23 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2023/sep/22/vanya-review-duke-of-yorks-theatre-london

[4] Andrzej Lukowski (2023) ‘Review’ in Time Out (Friday 22 September 2023 online) Available at: https://www.timeout.com/london/theatre/uncle-vanya-20-review

[5] Barekat, op.cit.

good analysis. I loved the streaming of Vanya. Andrew Scott brought so much passion and emotion to each role. How he does this and remains sane, I do not know.

LikeLike

So agree. There is a such a strong ability to dissolve the real into the imagined in him. True of him in ‘Present laughter’ production too, but certainly of All of Us Strangers — but who knew Paul Mescal cou;d do it too.

LikeLike