The most important invention in your lifetime is…

The term invention has an interesting etymology, for the idea of merely ‘coming upon’ or even ‘discovering’ (taking a cover from something previously hidden under that cover) is a relatively passive idea compared to the concept of ‘creation’, although in practice it involves activity of an equal size if not of type. So the difference between the two terms, which is important to the way I want to answer this question, does not lie there. Both terms imply a process by person or persons, or an agency, or combined set of agentic forces, which makes something by a combination of elements not before successfully tried. However, the ‘creator’ passes something over to their ‘creation’ a quality of continuing being of which the creators themselves are not in total control – or have not totally intended or determined.

In contrast, invention has no truly ‘creative’ or autogenetic force to transfer to its invented object. Invention is then nearer to what we might call ingenuity rather than creativity. And creativity looks and feels different, therefore, from mere invention. It is Frankenstein’s monster before the latter acquired the ability to motivate itself. This is a process better illustrated in a novel by Alasdair Gray’s Poor Things (see my series of blogs accessible at this link) than in Mary Shelley or the films that popularised her ‘creation/invention’ (decide for yourself.

Even a true work of art, in order to be true, has this quality of semi-independence of its maker in the thing of its making. If that had not been the case how would or could director Yorgos Lanthimos have made such a beautifully different film, itself a creation, of Alasdair Gray’s novel before mentioned. Of course, both invention and creation usually require the use of raw materials. For, although the idea of creation from nothing is talked about in myths of divine origin of the world, it is a practice usually reserved for and definitive of the divine. For, to repeat myself, all creation must imply the making, not only of something that has not existed before, but a thing that has its own, at least semi-independent, being. Such ontologies require the thing made to have a life capable of developing after its creation without prescription, or at least with a degree of the non-prescribed. There is nothing, even in Artificial Intelligence (AI), that matches that requirement except in an illusory appearance of making such a match.

The requirement may even be matched in the smallest of ways that are nor merely illusory but the created thing will have the capacity to co-create by its own will and agency its own meaning (semi-) autonomously of its creator or the creator’s intentions for that creation. Invention is just of a thing that hasn’t existed in this form before but not of a thing capable of autonomously developing things with at least a minimally effective degree of self-consciousness and agency. Created things have the ability to generate their own independent motivation, although science fiction is a genre based on that fantasy being possible in the invented. Such genres feed from our wildest fears of the runaway power over human life of Artificial Intelligence (AI) or of genetic engineering.

There has been pressure in some of our our cultures of late postmodernism to break down any distinction between the invented and the created. In some postmodernist schools of thought distinctions between humans, animals, and machines are false distinctions, for all of those constructions of thought are in its framework of thinking constructions or inventions and primarily the stuff of ideology not ontology. Yet, I don’t think this particular postmodern route is a useful paradigm for thinking of what I would call creation, though some elements of it are helpful in defining ‘invention’. Indeed the best definition I know of invention online after a search is that of the Encyclopedia Britannica: “Invention (is) the act of bringing ideas or objects together in a novel way to create something that did not exist before”. It is a definition that implies an agency of construction just as the term ‘creation’ implies a ‘creator’ (if we choose to use this word to describe a thing. But these agencies, inventors in this case, are, in the same source of definition, merely ‘persons who brings ideas or objects together in a novel way to create an invention, something that did not exist before’.

We should beware the tautology here between these two definitions perhaps but let us not do so, for the only agency of invention here, in this useful definition of ‘inventor’, is a ‘person’ (a human being). To extend the range of possible agents to include a divinity, or transcendental force, seems to me an obvious absurdity for such forces cannot be conceived as mere pragmatists. And though animals or machines might so act, in the later case be programmed so to act by human persons, we can go further for, in practice, these ‘persons’ are further reducible to certain categories of person. Wikipedia even gives a whole section of its web-page on the concept to what it calls a ‘gender-gap’ in invention, that argues that, even where women are struggled against the structural disadvantages of sexism in capitalist society – in terms of access to intellectual and other forms of capital, they are less likely to be thus recognised in this personal role:

Historically, women in many regions have been unrecognised for their inventive contributions (except Russia and France[30]), despite being the sole inventor or co-inventor in inventions, including highly notable inventions. Notable examples include Margaret Knight who faced significant challenges in receiving credit for her inventions;[31] Elizabeth Magie who was not credited for her invention of the game of Monopoly;[32] and among other such examples, Chien-Shiung Wu whose male colleagues alone were awarded the Nobel Prize for their joint contributions to physics.[33] Societal prejudice, institutional, educational and often legal patent barriers have both played a role in the gender invention gap. For example, although there could be found female patenters in US patent Office who also are likely to be helpful in their experience, still a patent applications made to the US Patent Office for inventions are less likely to succeed where the applicant have a “feminine” name,[34] and additionally women could lose their independent legal patent rights to their husbands once married.[35] See also the gender gap in patents.

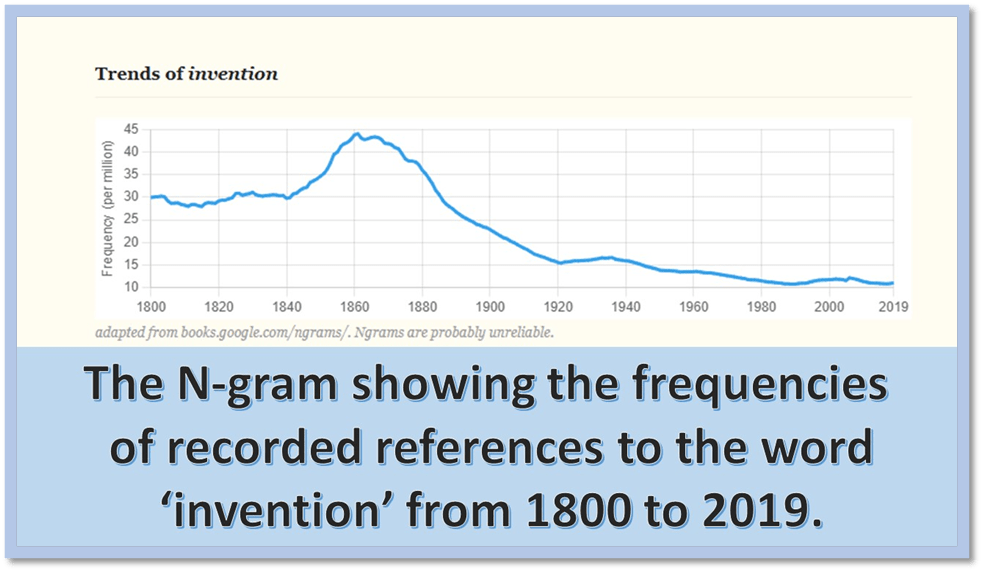

In fact much the same can be said of other marginalised or oppressed groups for inventors are usually persons reducible to to certain categories: white male enabled and pre-resourced bourgeois persons, or people serving without autonomous rights, such as wage slaves or otherwise bonded or contracted people. And this is reflected in the use of the word ‘invention’. Though Google n-grams are notoriously lacking in reliability as a demonstration of statistical truths, they have a working validity for thought experiments, which is what blogs ideally are. Let’s look at a Google n-gram for the work ‘invention’, which appears to show, unreliably of course, that the word reached a maximum peak of use in 1860 or so: in the middle of the nineteenth century, with a peak between 1850 and 1870, and the development of patriarchal industrial capitalism and the free-trade entrepreneurial ideal in British socio-political discourse in common use.

Taken from: https://www.etymonline.com/word/invention

We would indeed put the explanation of this peak down to the ideology of entrepreneurship and its historical alliance with, or sometimes usurpation of – in the type of the French bourgeois revolution, the role of social and political governance led by landowning aristocrats and symbolic figureheads such as kings, generals and priests. The aim of this class or class alliance is to be the leading force in the definition of the social engine. Even that last metaphor for social dynamism is one essentially of that time, the apotheosis of the machine age.

And these people have (namely ‘white male enabled and pre-resourced bourgeois persons, or people serving without autonomous rights, such as wage slaves or otherwise bonded or contracted people’ as I phrased it above) a vested interest in seeing ‘invention’ as the concept of greatest interest to ‘humanity’ as they defined that last concept, with a basis in individualistic white male values of self-interest as the primal force of innovating growing economies and self-orientated cultures and measurable evaluations. Men, in as much as they formed in patriarchal models, have an interest in confusing creation with invention I would dare to go on to say. Creativity has too much alterity in it (an interest in ‘otherness’ and the interests of the other as well as the self) since it creates new semi-independent agencies rather than slave-systems under the ultimate control of inventors. The very nurture of the created does not guarantee payback, as is obvious in the (dialectical) praxis of child-care.

And the mid- nineteenth-century peak in the use of the language of invention has another corollary, often studied best in the context of the ‘bourgeois revolution’ in France – that of the rise of the ideology of ownership of the ‘made’ as well as ‘the unmade’ (land and resources) in the ideology of patent and copyright for creative ‘genius’ across all realms (technological or ‘creative’) of human activity. I addressed this in a brief response to a question about the nature of copyright law as a revolutionary principle in France on a course I once studied. See at this link my response to that question and the document, from 1793 in France, I was responding to. It is clear even there that I believe the case for a reconfiguration of our notion of the truly creative, as liberatory rather than reactionary, is still going on at deep structural levels of contemporary socio-economic and political life:

This belief in property rights as inalienable rights will become the trademark of bourgeois revolution. It institutes itself on a belief in unequal distribution of talents, founded on the example of ‘genius’. Genius is never equally distributed – if it were it could not be recognised as such and there would be no reason to separate our feelings about the fate of Corneille’s children from those of the children of every (wo) man. And if our belief that intellectual property is the ‘most incontestable’ can only be a step away from a New-Right’s (the neoliberal) justification that property itself is not the source of inequality but rather the natural and diversity of the qualities of its holders.

Extract from:https://livesteven.com/2021/03/02/copyright-law-and-genius-in-france-1793-a843-ex-4-3-1-written-2017-reproduced-from-ou-blog/

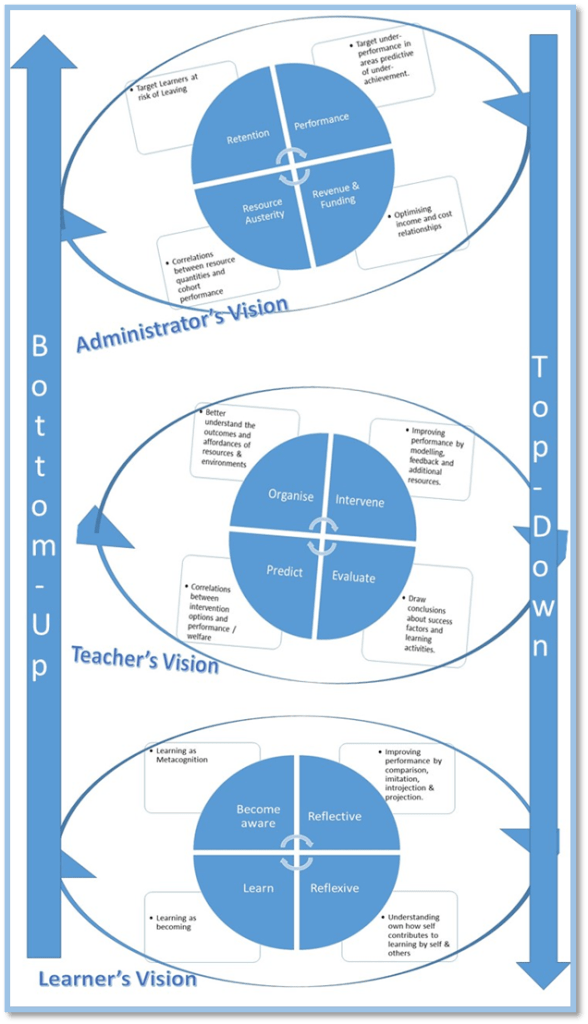

Nevertheless I am surprised by the decline of the use of the word ‘invention’ as the n-gram shows it into the twenty-first century and the age of the ‘digital revolution’. I have not checked but I suspect most answers on this question have plumped for ideas that are positive or negative about that ‘revolution’. But the digital revolution itself and the tendency to police words rather than things for their negative function may be responsible for this. For digital technology is a prima-facie case of invention rather than creation, yet some interests have attempted to represent it as ‘creative potential’ rather than a commodifiable invention and inventive process, enabling further invention. It has lauded itself as the secret of creative teaching (indeed having successfully completed a MA in Open and Distance Education at the Open University I probably bought into that idea myself - see this blog and the one referenced for the diagram below as evidence against me – although as always for me it is eccentric in its manner of argument).

Blog source still available on 07/02/2024 at: https://learn1.open.ac.uk/mod/oublog/viewpost.php?post=177412

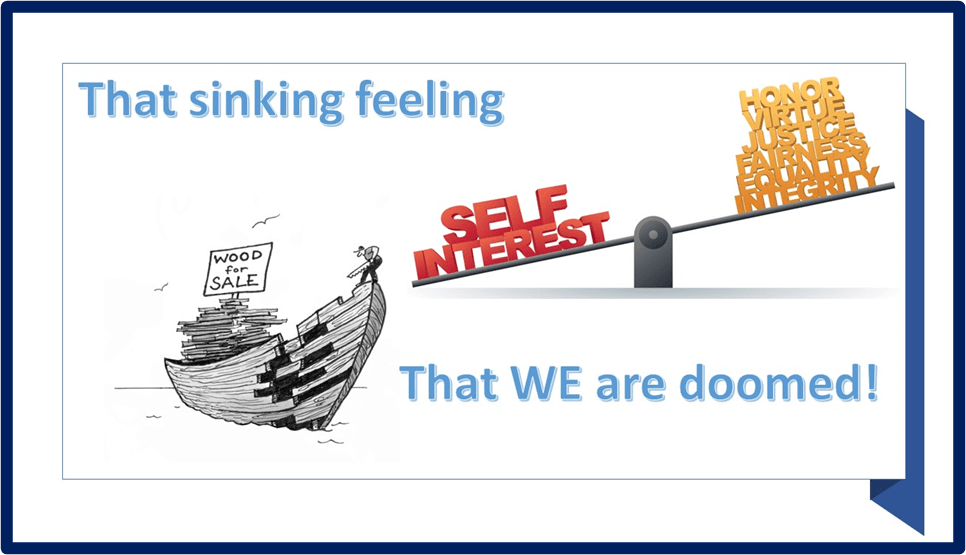

Whether In my experimental models above, produced in a learning exercise, or in more authoritative sources on the digital revolution in teaching / learning, there can be automatic passage of autonomy in fact in the digital revolution or the ‘invention’ of ever more complexly networked methods of personal computing, such as those that mark the advance of mobile (or ‘cell’) phones, and remote technologies, or in invented models for its use as a teaching tool. For these inventions have the unfair distributions of ownership and control built into their conception from invention to usage and are controlled ultimately by power bases motivated by self-interest and maintenance of the structural status-quo. Even the attempts to make the latter processes subject to the control of governments, even ‘democratic’ governments, will not ensure the technology will feed marginalised people, and species – for animals too are implicated, as generously as they nourish the self-interest of the few.

Only a reconfiguration of the socio-economic and political structures invention serves can achieve a fair use of those inventions for the interest of the many and ‘Others’ and the entitled few. Above i pointed out, as Wikipedia, does that the idea of ‘invention is inevitably locked into notions of copyright and patent law, that has even reduced the arts to a degree of necessary commodification and the furtherance of oppressive practice. And in that reconfiguration, the role of the ‘creative’ needs a fairer place in systems of education as well as governance and the curation of diverse bodies and minds. In fact I don’t think we have much time. For the various issues named ‘environmental issues’, ‘species-extinction prevention’, global climate pattern concerns and so on are really ONE issue – the dangers that the primacy of invention over creativity have placed us in.

With love

Steve

One thought on “Try this for ‘significant invention’! LOL. The decay of the idea of ‘invention’ and making space in the cosmos for the creative life-forces may be all that matters.”