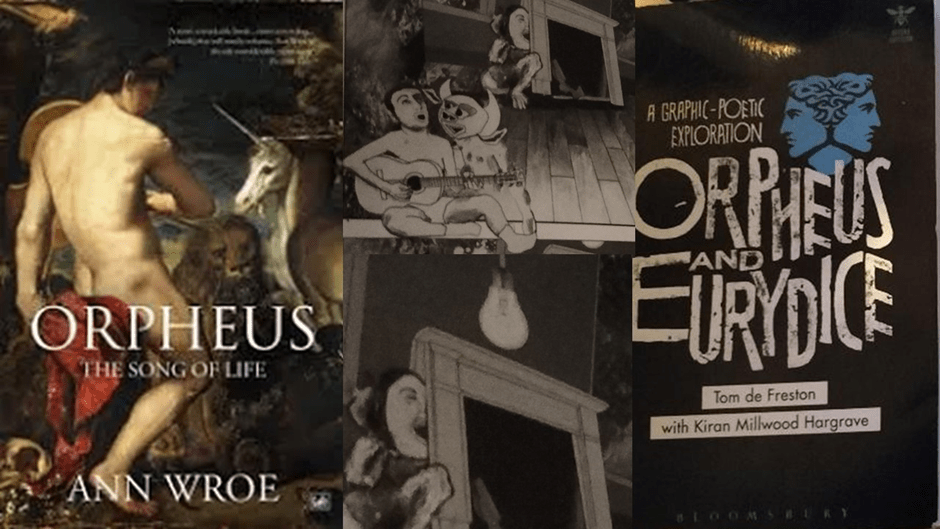

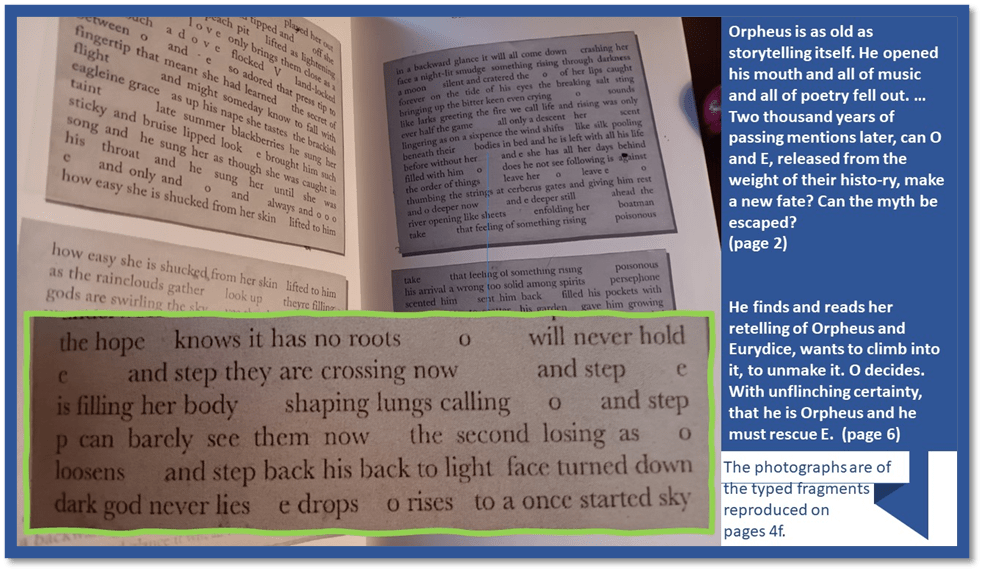

‘Orpheus is as old as storytelling itself. He opened his mouth and all of music and all of poetry fell out. … Two thousand years of passing mentions later, can O and E, released from the weight of their histo-ry, make a new fate? Can the myth be escaped?’[1] So starts Tom de Freston with Kiran Millwood Hargrave’s 2017 multi-media retelling of the story, based upon their own mutual biographies. This blog explores Tom de Freston with Kiran Millwood Hargrave’s 2017 book Orpheus and Eurydice: A Graphic-Poetic Exploration London & New York, Bloomsbury Academic and its debt to Anne Wroe (2011) Orpheus: The Song of Life in the Kindle ed.

Once you have Orpheus in your life, he keeps on making ghostly appearances, the validity of which is sometimes questionable. Recently, I found references to him in Rapture’s Road, a new volume of poems by Seán Hewitt and compared him as a cultural icon to the life and lyric autobiography of Lou Reed ( connect to those blogs at the links on their names). And debating his presence is where I intend to start here before I look at the way in which a work describing itself as A Graphic-Poetic Exploration makes part of his story problematic in that it is not JUST his story but that of an active force in life, art and other narratives, Eurydice (or E) who, as Sarvat Hasain says has before being given only the role of she who ‘waits outside her story’, totally passive to Orpheus’ (or O’s) actions.[2]

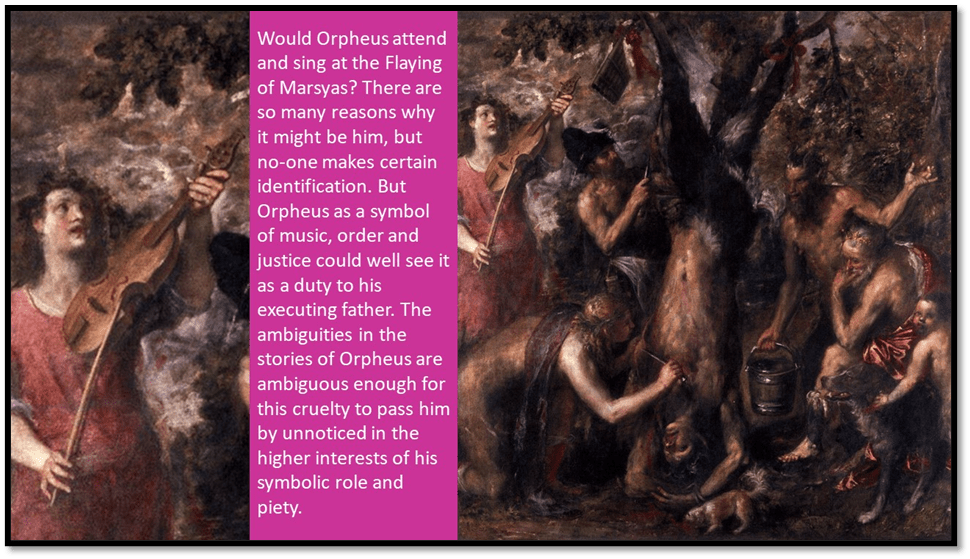

One artwork that I think relevant is one that so absorbs me, we have a largeish reproduction in our living room (much to my husband’s horror). It is Titian’s The Flaying of Marsyas, a painting of torture in the supposed name and glory of artistic excellence.

Our living room. The sculptural pieces are reproductions of an attendant ritual kouros, Apollo bust, a satyr (reproduction from the BM – is it Marsyas?) and John Milton bathed in lamplight.

There is no authority in saying that the figure in detail on the left of the collage below is of Orpheus; about that Titian himself was silent, as far as we know. An authority on the painting’s iconography, Edith Wyss, leaves discussion of the possibility to a scholarly footnote of her DryasDust, but fascinating, study of the origins of its iconography, which I will quote, once you have seen the visual evidence in the painting as shown in the collage:

Of that near-androgynous ‘musician’ on the left (which is all that Wyss cautiously names him) all we can definitely say is that he plays on the lira da braccio (often the substitute for the Greek lyre in Renaissance versions of the ancient and mythical music-maker) and sings so artfully and intensely that he clearly sees the barbarity of the actions of the painting as justified, if with a certain sadness in his expression of it, by art and natural order. That justification is also how quite unambiguously and without sadness (so hopelessly ‘modern’ an emotion we are told) Wyss reads the painting scorning modern sensibility – typical art historian – about medieval torture methods in the process. Wyss does say (in her footnote) that Jürgen Rapp in the 1980s:

… identified the musician as Orpheus and illuminated his significance by the Neoplatonic Orphic mysticism. As son of Apollo and protype of the inspired poet/musician, as founder of the ancient mysteries, and as mythical first teacher of the sacred Pythagorean proportions, Orpheus could have been an apt choice for Titian’s lira player. I believe, however, that Titian’s prime concern was to find an embodiment of the power of harmony. … If the artist was indeed thinking of the musician in mythological terms, Orpheus would have been a suitable choice, His wreath of vine leaves, which is difficult to see, points to the double nature of the highest ecstasy, Apollonian as well as Bacchic.[3]

After we have shaken the dust off that reading, we will find something substantial in its ponderous musings, not least the need to evoke two traditions behind Orpheus, that of the gods Apollo and Bacchus / Dionysus respectively, for as we move on in this blog we will find it important to invoke Nietzsche’s references to the fundamental tension between creativity and destruction in these traditions, in Greek drama of course but perhaps also in life. But for the moment, let’s just rest on the fact that Orpheus can be invoked in contexts where his presence is disputed, doubted or merely (as in Wyss’s case, less than certain. He is changed in the versions – made as it were contemporary to the retelling. We will see this in Tom de Freston’s work also. One example of the anachronisms that reinterpret Orpheus in Titian would be, for instance the substitution of a Greek lyre for its Italian Renaissance equivalent. Compare it to the Greek lyre we see in the third century BCE krater below, showing Orpheus in Greek attire but living among the Thracians, the supposed place of his birth).

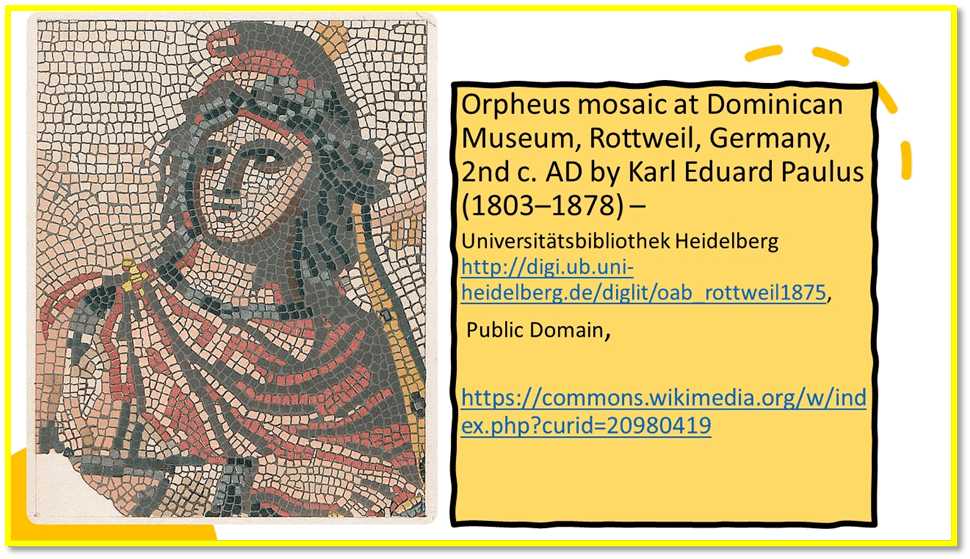

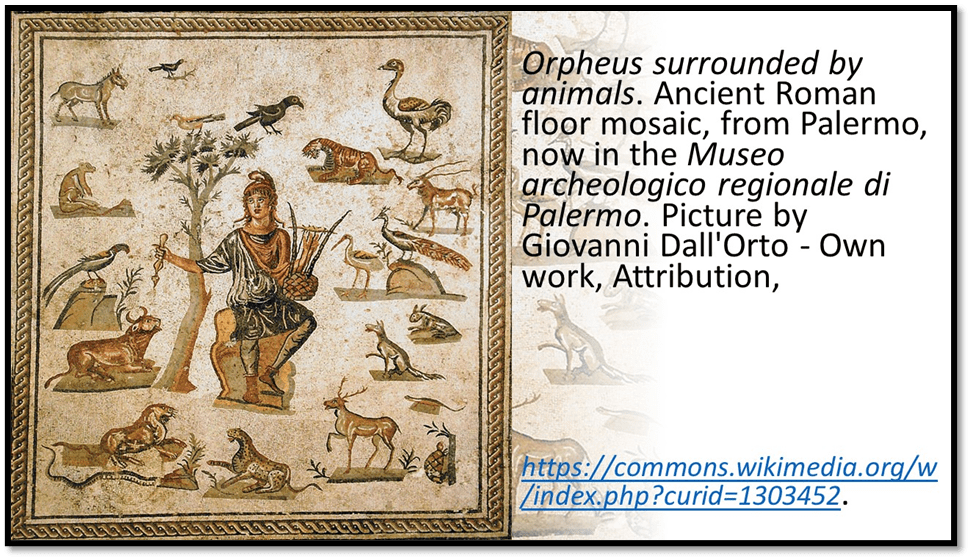

That man is guarded on that krater from petition from a man with a scythe in his hand. He will continue to assume his right of special treatment and power up to the time of the Roman Empire and beyond when that Empire transformed to a Christian Holy Roman Empire in the Byzantine East (speaking Greek mainly) on the one hand and fragmentation in the West on the other hand as a result of being under the attack of Northern European and Slavic forces. We see him in splendour in a mosaic from Germany below too from the a picture in mosaic from the second century AD. It is a lovely mosaic wherein Orpheus engages his audience with his adorable eyes rather than by just his music alone.

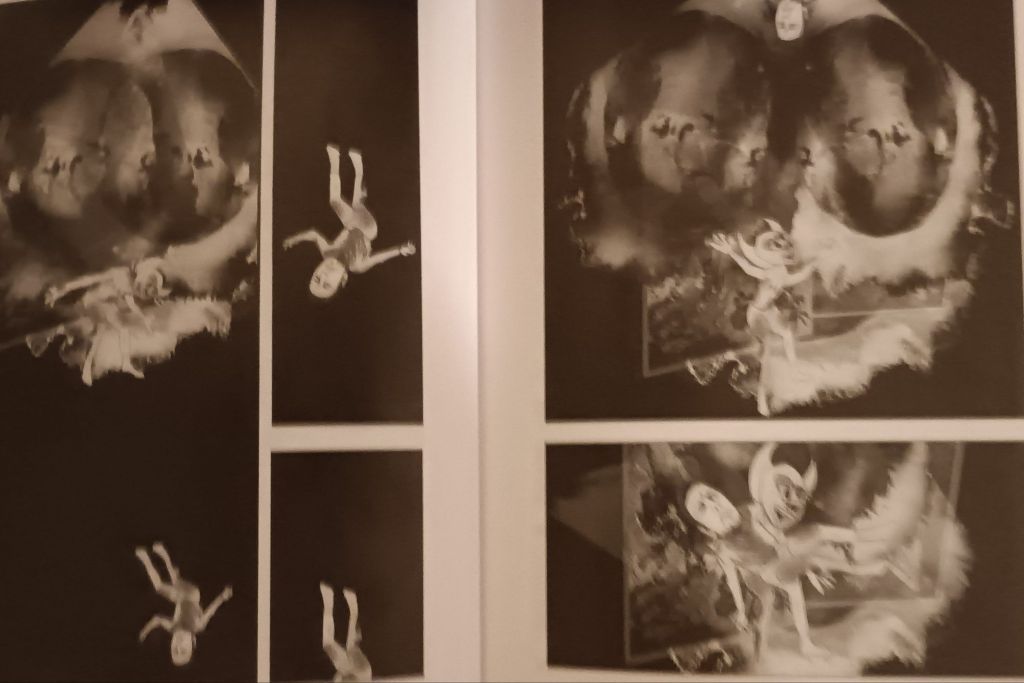

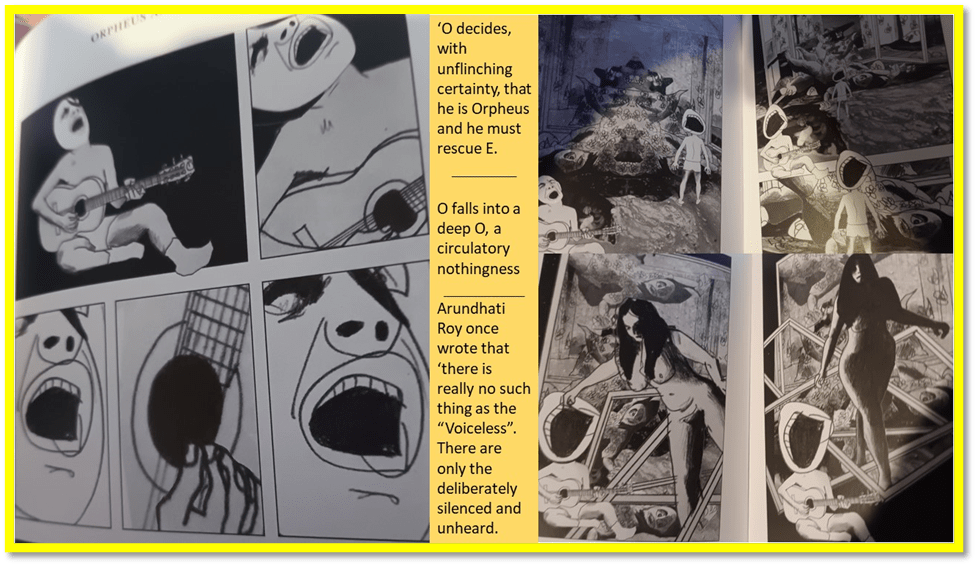

The historical diversion above can help us leave Titian for now in order to return briefly later in this blog to the ambiguous Orpheus (absent/present, male/female, creative/destructive) as the greatness of Titian’s complex artistic vision employs him, if he does, to say something about patriarchally-determined gendered traditions of creativity. For me this latter point matters because I think Tom de Freston finds in his ‘O’ (for Orpheus) character (and an avatar of Tom himself), the very nature of blank uncertainty at his centre as male, husband, and artist. However I say this metaphorically, for the qualities required by those roles can only be at the centre of those things, if that character has a centre on which it rounds, because the ‘O’ that O in fact is may be a black hole without substance, an empty pit or void of hell or a bottomless mouth (empty but for echoes from within, where darker depths have displaced any central certainties): ‘O falls into a deep O, a circulatory nothingness’.[4] There is a moment in the graphic narrative that is a ‘fall’, like that of the rebel angels in Milton.

pages 106f.

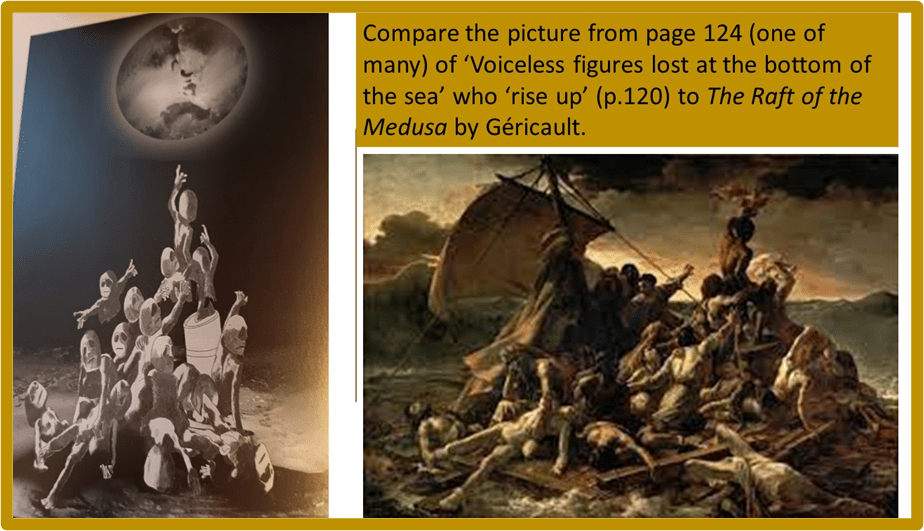

This fall is also prefigured in the mouth of his singing and other potentially deep holes and orifices in the objects of the world, and particularly that mouth (his OWN) that opens up as a ‘voice’ to silence all others. The text has a beautiful prose poem containing this ambiguity in O, opposite Ruth Graham’s potent essay ‘The Voiceless’, on the silencing, negation or obscuring of women’s voices, especially E’s own story of E, overlaid by O’s version: ‘When Orpheus sang the whole sea stopped’. When your primary effect is stopped the dynamism of the world what could be saying of ‘all music and poetry’, if we say of his open O-shaped hole: ‘He opened his mouth and all of music and all of poetry fell out.’ And is fair to turn all history into hist-ory (a story of O)’. [5]

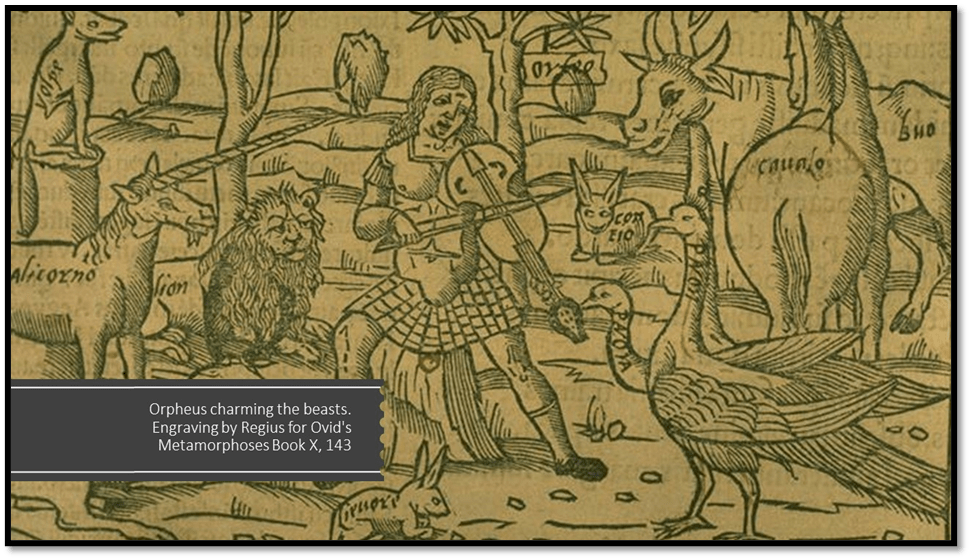

Sometimes O becomes the O of his mouth which is also the hole in his guitar, the twentieth century substitute for a lyre as the lira da braccio for the Orpheus of the Renaissance, of which Titian may have painted one. E, who is also at one allegorical layer, Kiran enacting Eurydice is crushed by the voice of the lover attempting to ‘rescue’ her as patriarchally en-scripted males are wont to do until, feeding the hole as she goes by, she passes away from it unseen, for the mouth has covered O’s eyes and ears totally. As for silencing, this feeds off the traditions of Orpheus as a man who makes all species lose their nature as we and they know it and enact an order of his making, Such as Ovid painted him in words for Augustan Rome. Later medieval and post-medieval illustrators merely made a contemporary avatar of that man who stopped everything but the need to listen to him, and him alone.

Such myths had use for Romans, in Ovid’s time, a supposed golden age restored as Augustus wanted his subjects to believe and to the Roman colonists later, say of Sicily, where the mosaic below, showing a similar and more convincingly stopped scene, except that Orpheus here seems more pragmatic, ensuring peace amongst the warring by controlling the space between them.

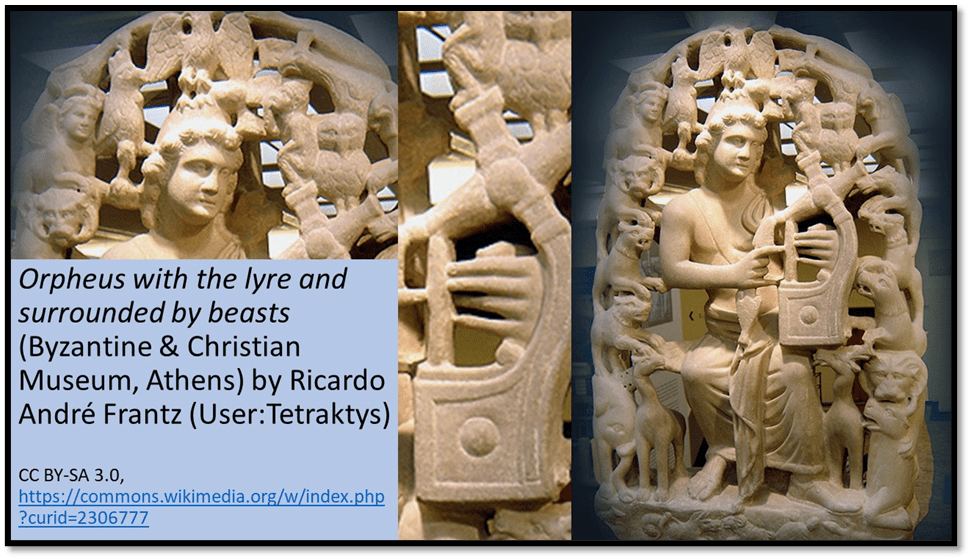

For the Eastern Roman Christian Empire and its church of patriarchs, this image of Orpheus as a man who embodies love and authority that speaks through his voice and divine instrument, as Christ needed the divine instrument of the Byzantine Church and State, could make Orpheus into an avatar of Christ, but one instinct not only with love but a love that is powerful and enforces the pax Romana in the Christian Empire (an enforcement more bloody and conflicted than the word ‘pax’ suggests to most of us. This Orpheus as an allegory of Christ, needed as the Empire veered between commitment to Christianity or regression to apostasy that the bishops faced daily, using ‘pagan’ tools to figure out their own version of Christ, they cemented a socio-political version of Orpheus as strong as that of Augustan Rome.

These political usages of Orpheus almost certainly continued when there was a necessity to validate the idea of great Leadership and central control by rulers where such leadership and control was largely illusory. You can almost see that in The 1854 Gabriel Thomas Orpheus at the Louvre Palace to celebrate the Second French Empire under Napoleon III (a shadow of his forebears), where a rather forlorn and lonely character of Orpheus posed as a classic kouros, with his lyre (now back to neoclassical style – although even a little contrapposto stance seems too much for him) stands as forlorn as he at its use in this rather vapid iconography.

The USA was not to be kept out of the act. The Neoclassical impetus survived a long time in the United States. When it was decided to commemorate the Battle of Baltimore of 1814, a decisive sea-battle against the British imperialists in 1914 (though the project was delayed by the First World War) Charles H. Niehaus (born in 1855 in Cincinnati, Ohio of German immigrant stock so a true son of the States in the naturalising mythologies of the Republic) was commissioned. The monument would bear an inscription to Francis Scott Key, the ‘poet’ of the nationalist hymn, The Star-Spangled Banner. Clearly the heavily-in-demand neoclassical Niehaus was alive to the need for male sinews in his classical mimicry in the interests of figures of heroic patriarchal power. His Orpheus of the Awkward Foot may seem too much – not least the capacious pouch made by his de rigueur fig-leaf - but the strong contrapposto attitude (it in fact creates the ‘Awkward Foot’) goes with an almost careless playing of his lyre from the hip, as it were, as you will see below).

This is the context of historical reception of the Orpheus myth we need to address, for if the myth hails patriarchal heroism in some anachronistic uses, especially where ‘common men’ became Emperors and perhaps even tried to play Gods (as Napoleonic dynasty made clear but more particularly in the USA), it is clear that Orpheus id a figure worthy of some negatively critical interest rather than of laudation. Pablo de Orellano, a student of wars in history says that the story of Orpheus and Eurydice as retold by Tom de Freston with Kiran Millwood Hargrave, known as OE, ‘lays bare the problematic assumptions behind the story of the common man becoming a romantic hero’.[6]

Thus far we can see why this necessary – but why do this in terms of the story of Eurydice, which plays only a small and late part (in its development of the myth. Thus far the association of Orpheus in the nineteenth and twentieth century with nationalist and imperialist aspiration in the picture story I have briefly indicated would illustrate the fact that myths of greatness arising from the mass of common men to validate an ideology of patriarchal rule is already illustrated. However the quotation from Pablo de Orellano I gave above, does not stop where I stopped it. He goes on to say of ‘the problematic assumptions behind the story of the common man becoming a romantic hero’ that: the result in OE is ‘nothing short of a philosophical slap in the face of gendered identities’.[7] This takes us back in history I think to the historical reception of the mythologies of Orpheus again through the ‘multiplicity of variants bleeding into one another’, for each version signals ‘a further shedding and rend in past certainties’, in Stephen C. Kenyon-Owen’s words.[8]

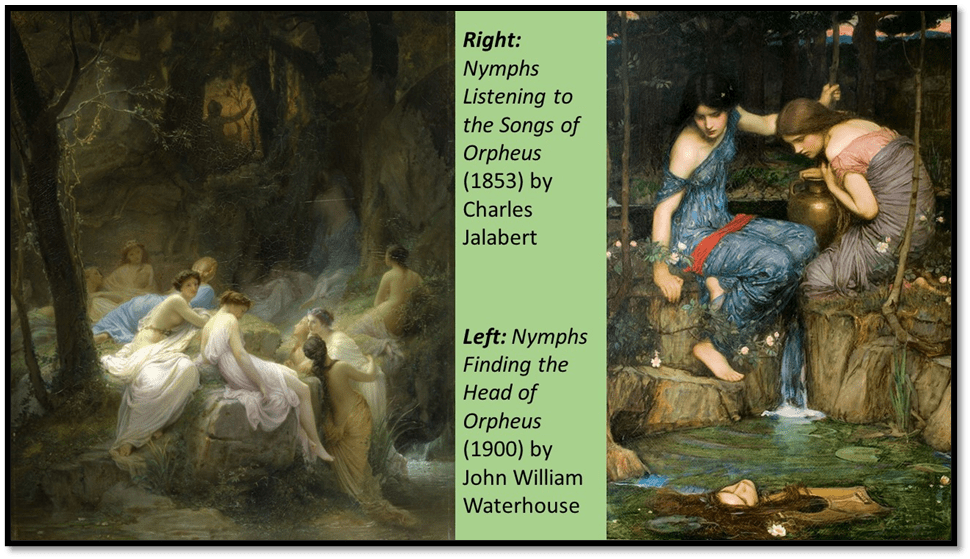

We need to return to the Second Empire where we saw Gabriel Thomas making a rather frail imitation of the male masculine ideal for the huffery-puffery that was the man Napoleon III. If it is difficult for a sculptor or painter to realise ideal masculinity now, as did not seem a problem for the early painters of the early Revolution and even of the First Empire like Jacques-Louis David, I think I would suggest that this is because male ideals were being used primarily to sell a myth to women that silenced their own aspirations to power, except for giants like the early feminists, who were unreachable with soft soap, such as romanticised versions of classicism were purveying. Charles Jalabert, also in the Second Empire, turns Orpheus into a shadowy icon in the background (barely seeable but for the arm of a shadow cast on the wall of an interiorly lit cave in the background. The arm is stretched to the top of a lyre. What the painting asks us to do is to imagine hearing the hidden voice and play of this secreted man which can be heard, if at all, only vicariously through an enchanted (literally) group of Second Empire ladies dressed as Nymphs (dryads which is the role in which Eurydice started in Greece and naiads) of the painted foreground of forest and river respectively. Of course not all these nymphs are fully clad; some have turned their full frontal nudity prudishly for only the mythical-barely-seen-but-felt presence of the singer to see, were he to peer from his ‘O-shaped’ cave mouth.

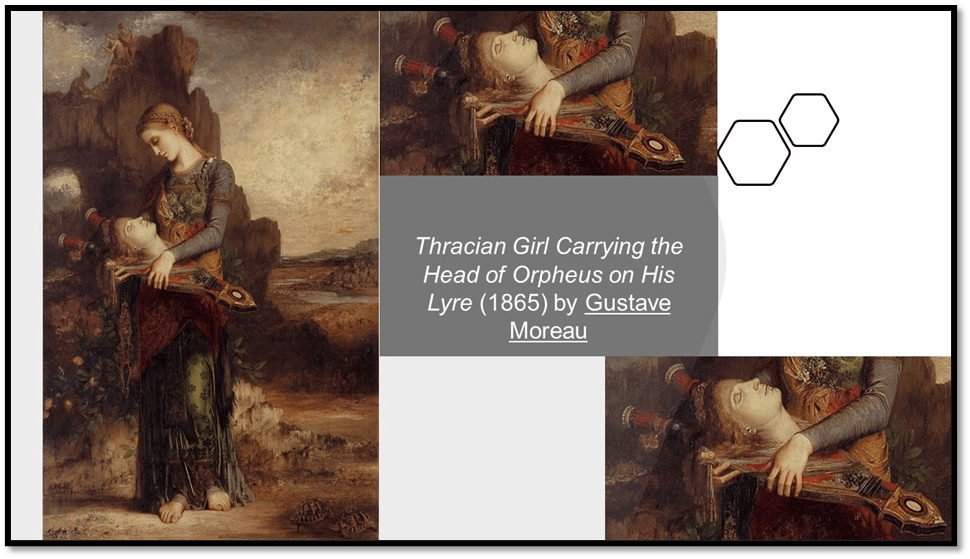

In England, bohemians of the later century had caught up, though the naiads are considerably more fleshly than Jalabert’s in John William Waterhouse’s Nymphs Finding the Head of Orpheus. They are still rendered as listeners primarily for the find the head because, even severed from the manly body it once occupied, it still sings, like a severed mouth (or ‘O’) than a whole head. And in both cases the hero is not depicted or seen for it is the ‘male gaze’ itself, seeking satisfaction from the drawn flesh of women reduced to passive acceptance of its power. However, this may reflect the nature of these particular artists passive to the zeitgeist that was then culturally hegemonic. In painters of greater substance, the gaze the sexual-political zeitgeist, even when present, is interactive between male and female, even at the level of looking at a picture, as in Gustave Moreau’s Thracian Girl Carrying the Head of Orpheus on his Lyre (1865) – see below. It is the woman who bears the burden of the tradition here and, as far as xenophobic Ancient Greeks were concerned, a barbarian woman – a Thracian, a woman from the land of Orpheus’ purported birth.

The pushback from a situated feminine perspective, which is what I – at least – see in Moreau, can only be understood as a contribution to a very fluid situation in which sex/gender ideologies were shifting, as we indeed know them to be in the Europe of the period. Such tensions persist but are raging even in the twenty-first century. Hence Pablo de Orellana’s view that OE is ‘nothing short of a philosophical slap in the face of gendered identities’. [9] O very much wants to be the romantic hero of OE. His role, as we have seen, is the self-appointed one to ‘rescue’ E, just as Tom de Freston suggests, since the book is ‘a dialogue of lovers’ that,[10] in the wake of the loss of a baby by his wife, Kiran Millward Hargrave, he felt he should ‘rescue’ her and her work, including ‘her retelling of Orpheus and Eurydice’.[11]

I have already indicated above how O uses his ‘O-shaped’ hole, from which projects his commandeering voice, to fragment and silence Kiran and E as much as attempt to collaborate with her. His story (or ‘hist-ory) keeps taking over, with his artistic and other preoccupations to the foreground. Indeed it is not easy to locate E’s textual or graphic contributions. These are in the form of hand-written lyrics on paper that are photographed such as the beautiful and paradoxical recall of the Styx (the river and Goddess of Oblivion in the Greek Underworld): ‘all of us drinking / to forget – ‘.[12] The story otherwise by her I believe is told on photographic reproductions of fragments of typed text that appears from page 3 to 5 inclusive may be imagined to be her original ‘retelling’ which O aims to rescue, which tells of a secreted bond between p and o (Pluto and Orpheus) as he disobeys Pluto’s one command (deliberately perhaps in order to lose E again and raise his own stock as sole lone ranger of the masculine-only virtues he thinks he represents:

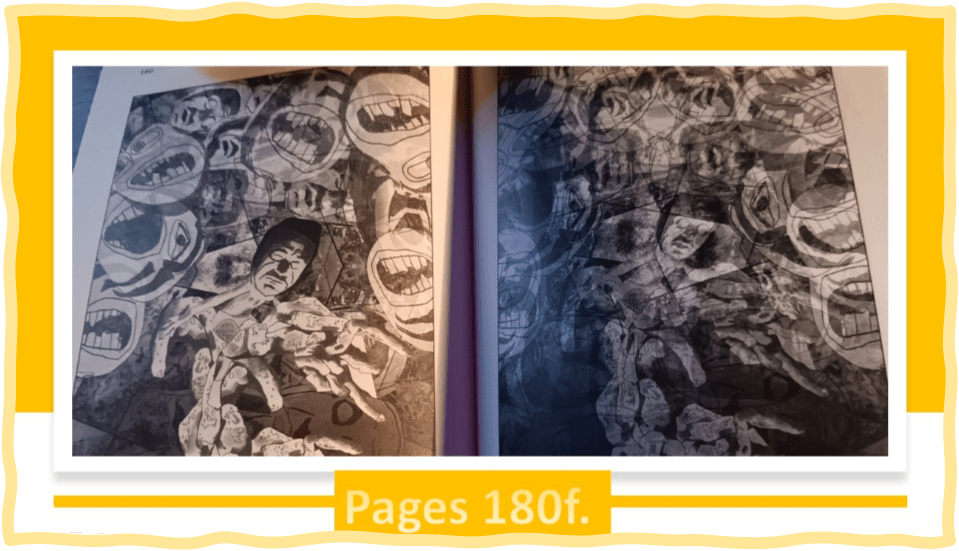

O has many models but all are of the romantic hero and often the Romantic poet-hero. He is Dante visiting the Inferno with Virgil, a source for the Orpheus stories after all, but in the form of his own body double with the head of Picasso’s cartoon versions of the Minotaur monster or Beast (in which Picasso himself showed up his own sexually predatory nature). He recalls even the bulb from Guernica in some frames of the story (see below for instance). He is Milton’s Satan with a crew of rebel angels falling and Faust with Mephistopheles (again the Minotaur) and prefigures his book The Wreck by being the entire cast of males on the painting (but not in reality – there were women there that Géricault removed) in The Raft of The Medusa (see my blog on this at this link).

And, of course O’s is also the story of the modernist artist, Tom de Freston among historical peers, as told many times by modernists Rilke and Anouilh as well as the postmodernist one of Cocteau (again many times) and all the material he acknowledges from Anne Wroe’s Orpheus: The Song of Life. These romantic heroes are queered ones – but more importantly they are narcissists and the queered only sometimes requires narcissism either on a range from its negative to its positive forms (I say that because the wondrous Matt Colquhoun (see my blog) has made me revalue the negatives implied with narcissism, even male narcissism). See the story on the pages below:

Pages 88f.

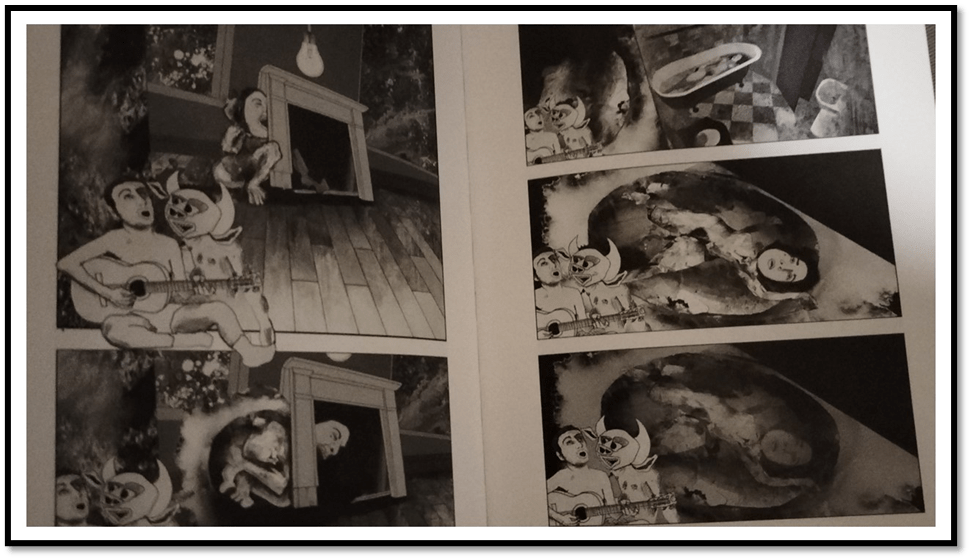

Here O / Tom has ears only for his double the Minotaur / Monster, though E / Kiran, always in the background is always disappearing through domestic holes like that Regency fireplace – her body being absorbed from its side. Or the hole absorbing her is her bath, in which she might die. Meanwhile the doubled-O still enchants its own monster, listening only to itself not the screams of the E figure, who eventually appears to have drowned unknown in a bath turning from a rounded rectangle to almost an oblong circular figure. How unlikely it is that he can hear E or read her as if he understood. In the Underworld ’E watches on, threading her memories out into kites in the hope O will pay attention and see one’. [13] Instead he ‘sings another story’ in which he relates to E only though ‘a puppet he made to conjure E’, and, of course, ‘failed’.[14] Of course, we have to remember that ‘O can’t hear, he is just one big O-shaped scream prodded by sight’.[15] It takes up to section XV of his story for this to happen: @For the first time, O listens, waits and hears a voice in the wind’. It is the first time he hears E effectively and then to little learning achievement, for he depends on his double-self (soon to become a kaleidoscopic set of reflections) not E.

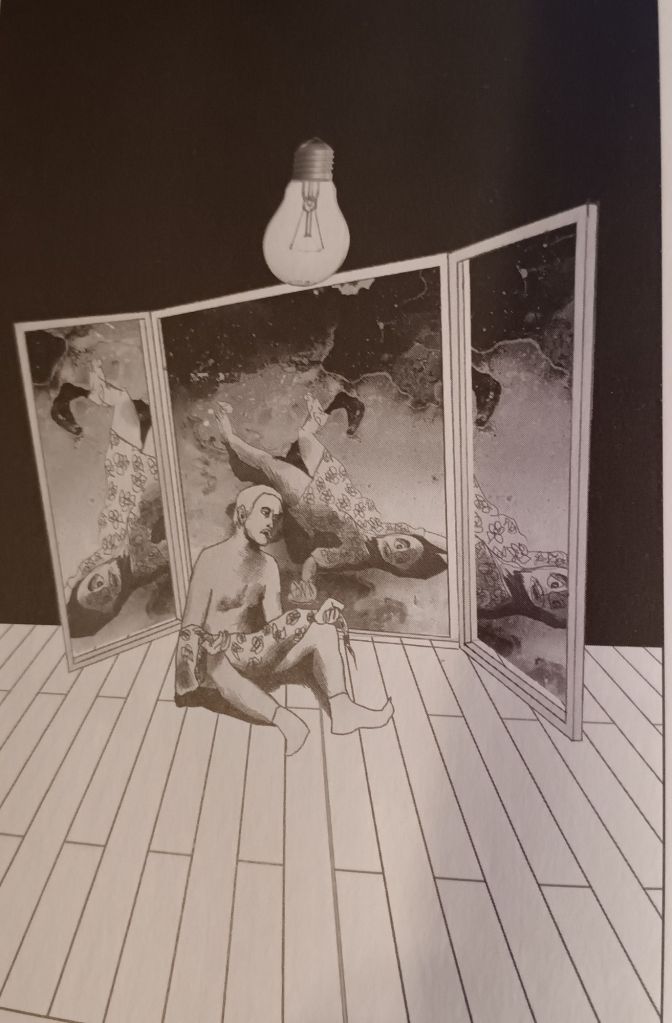

Anne Wroe in her contribution to OE says that O’s quest is fulfilled in ways that other contributors to the volume make us doubt. She says the E represents a lost wisdom that matters because, like any kind of tree (she is a dryad remember) she was rooted and once pulled out of the ground by O she is still rooted, but now singly in Death alone, and the wisdom that things pass.[18] She is, in her own words the knowledge that ‘the wreck already had roots’.[19] The book ends with O still alive watering a tree in memory f E in its text, but in its graphics it ends with E’s dead body tripled in the triptych artwork in his dark cellar studio which formed his portal to the Underworld as the picture of a wreck. He sits in front of these reproductions of her with only the dress she is wearing in his pictures next to his flesh (though he wears socks). His flesh though beyond the sock tops is drawn with more solidity than at any other point in the book (see below).

Ibid p. 226

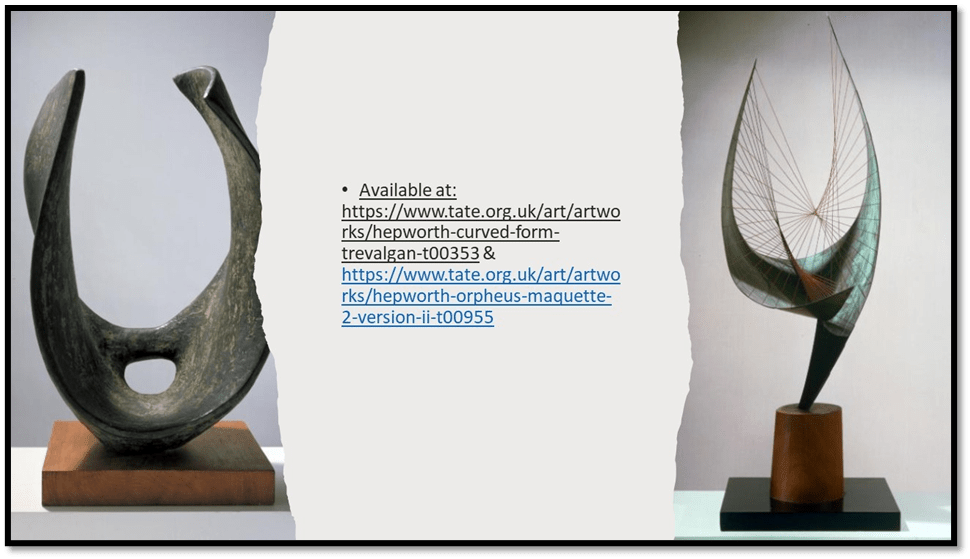

What are we waiting for? For him to dress as E and to deny the binary otherwise explored – his ‘double-self’ Minotaur having now disappeared. I sometimes think an androgyny drives the beautiful artworks with an Orpheus connection by the wonderful Barbara Hepworth (see the pictured works below and my blog at this link), and these are truly beautiful. And, to return to Titian, these works do not use an androgynous ideal, in the same way Titian does, if Titian does use Orpheus in The Flaying of Marsyas, to justify the cruelty of world order and to relish the male competitiveness it sadly plays and sings sad songs to. I think Barbara Hepworth is here in United Nations mode in every domain of politics.

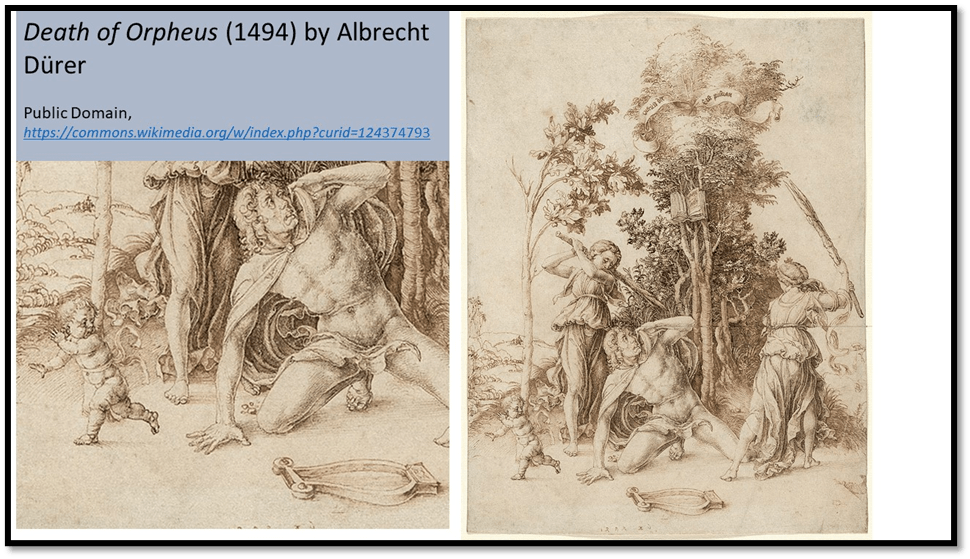

Other artists have explored the Death of Orpheus, but not Tom de Freston. Perhaps that is because the myths of the death of Orpheus are so sexually-politically ambiguous. In his maturity, Orpheus has withdrawn from life to a mountain top and is here hacked to death and torn into pieces and body parts by Bacchae – women maddened by the wine of Dionysus and possession by the God himself, as we see in the fine decorated silverware below.

Albrecht Durer in a 1494 drawing rather obscenely queers the idea by having the women less Bacchic than angry at a man, who having forsaken women after the death of Eurydice and turned to ‘pederasty’ (see the young child fleeing him as the Thracian women beat him. The legend on the tree is in described below (source at link):

… the banner hung in the tree reads: Orfeus der erst puseran (“Orpheus, the first sodomite”). The word puseran(t) derives from the Italian buggerone, which in its turn derives from Latin bulgarus from which come also the terms bugger in English and bougre in French. Though the drawing could be taken as a Northern European reaction to sodomy, it is actually based on an original, now lost, by the Italian master Andrea Mantegna.

For me this rather horrible image is Durer being a Northern boor, relishing his supposed difference from the sodomites of Florence and Rome (including the aptly named Sodoma). Other and later artists have resurrected the heroic image of Orpheus and the representation of what is best in humanity – art, poetry, beauty – to show in pictures of his death the threat to these values, as in the painting below by Antonio García Vega. As his Wikipedia entry says, these works ‘took a darker turn’ wherein García Vega describes ‘himself as “filled with rage and sadness”, creating art to fight against “dehumanization” and to express ideas such as oppression and loneliness. This painting haunts, wherein now Orpheus is already the victim, perhaps of rape and certainly of overwriting his youth, of its near neighbour’s capitalist imperialism.

It is difficult to find a copy of OE, but it is a work wronged if ignored, full of beauty and so innovative. And it is needed. Too many men are still wrecked by toxic masculinities of which the ‘rescue’ of women, which is as much from their own autonomy as relationships with bad me – though the latter matters too, is one now too much a favoured hiding place of patriarchy.

With love

Steven xxxxx

[1] Tom de Freston with Kiran Millwood Hargrave (2017: 2) Orpheus and Eurydice: A Graphic-Poetic Exploration London & New York, Bloomsbury Academic

[2] Sarvat Hasain In Essay ‘6: The One Who Waits’ in Tom de Freston with Kiran Millwood Hargrave (2017: 130) Orpheus and Eurydice: A Graphic-Poetic Exploration London & New York, Bloomsbury Academic

[3] Edyth Wyss (1996: 167 – footnote 17) The myth of Apollo and Marsyas in the Art of the Italian Renaissance: An Inquiry into the Meaning of Images Cranbury, NJ; London; Port Credit Mississauga, Ontario, Associated University Presses.

[4] Tom de Freston 2017 op.cit: 104

[5] ibid: 2.

[6] Pablo de Orellano In Essay ‘9: An O-Shaped Hero’ in Tom de Freston op.cit: 203

[7] ibid: 203

[8] Stephen C. Kenyon-Owen in Essay ‘1 (pages 23f.): A silent O’ in ibid: 23.

[9] ibid: 203

[10] Ibid: xii

[11] Ibid: 6

[12] Ibid: 25

[13] Ibid: 95

[14] Ibid: 114

[15] Ibid: 65

[16] Dan Holloway in Essay ‘7: Monster’ in ibid: 147

[17] Zata Banks in Essay ‘5: The original Mirrorball’ in ibid: 94 (whole piece is 93f.)

[18] Anne Wroe in essay: 8: Eurydice’ in ibid: 187f.

[19] Ibid: 228

One thought on “‘Orpheus is as old as storytelling itself. He opened his mouth and all of music and all of poetry fell out.’ This blog explores Tom de Freston with Kiran Millwood Hargrave’s 2017 book ‘Orpheus and Eurydice: A Graphic-Poetic Exploration’.”