How do significant life events or the passage of time influence your perspective on life?

I feel I need to get this prompt out of the way, for it poses as a question whilst being, in my view, at least, nothing of the sort. However, I do not say that believing that there are no other takes on the question and do not imply any disrespect to those who think and believe it worthy of serious answers. The love of diversity is consistent with my theme below. However, with the question itself, two things concern me.

- First, I feel that the notion that, just because I am ostensibly one person, I only have ONE perspective on life bears too many assumptions about the nature of personal identity, namely, to name but two: that first personal identify is unitary thing in itself, and that life can be summarised by one’s own limited view of it however many internal or external perspectives that view of life takes into account.

- The second concern is is that the judgement of whether a life event is significant or not is itself a variant between different groups and peoples across continua of space and time and differences of culture and/or conscious or unconscious ideology, as well as between individuals.

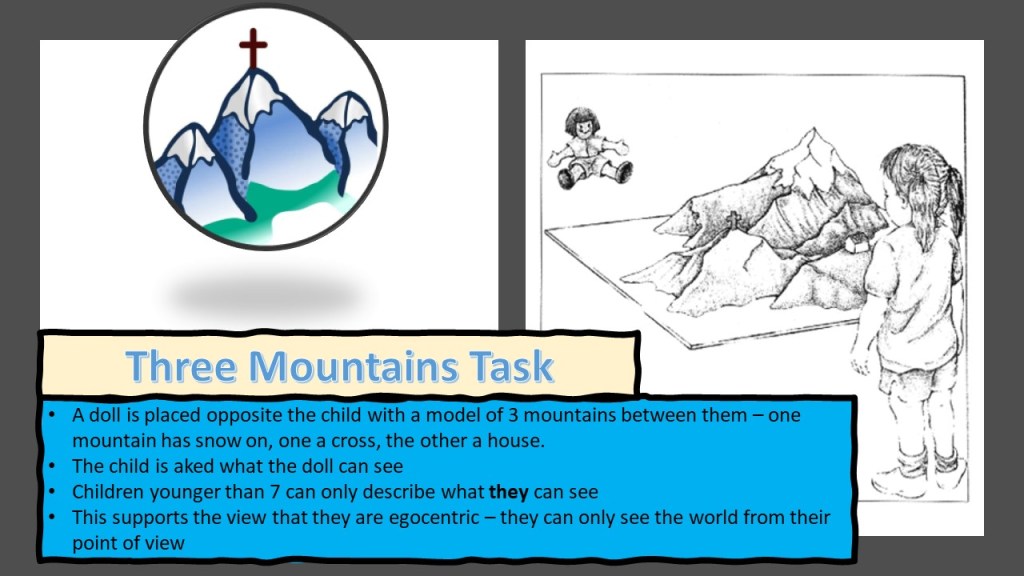

The notion that personal identity aligns with unity of perspective is, in fact, well established as a cognitive limitation of that kind of childlike magical thinking called egocentrism by Piaget’s translators. Piaget established his view of that ‘limitation’ using the famous three mountain task, where he asked children to describe the view of model containing 3 mountains that their doll had which was positioned opposite them as in the illustration below (there are of course many variations of this condition and this is a grossly oversimplified explanation). He argues, from the evidence of this task, and others, that egocentrism is normative for children under 7 years of age.

Of course the child is only describing a physical perspective in this task (though it has some ecological validity for these children were Swiss and used to surveying configurations of mountains. Physical vision can be thought to be apparently free of other determinants of what is seen like either sensation (other than sight) and emotion. But this test is often described as a test of empathy, implying a correspondence between cognitive egocentrism and emotional selfishness that it cannot support, though you might see the temptation to do so. But it should be enough to make us doubt whether our view of the world after age 7, and some would say before finding flaws in the experiment, ever consists of one point of view only, for the child eventually begins to imagine the perspective of others, questioning the primacy of their own perspective as sole evidence of what the world looks, and feels like to either the senses of touch or emotion. Hence, I think we have to conclude that. even in a simple physical sense, there is no unitary perspective on life that sums up any participant in it, at least when possessed of operational cognition (in Piaget’s terms), but rather a range of variant stances determined by one’s physical and imaginative situation at each moment of life.

The significance of a life event is particularly difficult to assess outside of the frameworks used for that judgement by a person. Theses judgements will not even be decided by circumstantial variation of history, geography, culture or perceived category of identity, like sex/gender/sexuality, nationality, age, class, status or perceived adequacy to an external standard of ability or intelligence.For instance, the rituals of the Simbari people, of Papua New Guinea, as studied by Gilbert Herdt one gave significance to the act of fellatio between males that cross with the significance attributed to events in male lives like ‘coming-of-age’. Yet these significances have changed across time according to Herdt’s later work and may, anyway describe norms that are not universal. The whole scenario makes it impossible to adjudge persons by even categories of sex/gender/sexuality except as these categories are defined by interactions of individual internal as well as external circumstances. Here is the summary first paragraph of the Wikipedia page on these people.

The Simbari people (also known as the Simbari Anga,[1] called Sambia by Herdt[2]) are a mountain-dwelling, hunting and horticultural tribal people who inhabit the fringes of the Eastern Highlands Province of Papua New Guinea, and are extensively described by the American anthropologist Gilbert Herdt.[3][4] The Sambia – a pseudonym created by Herdt himself – are known by cultural anthropologists for their acts of “ritualised homosexuality” and semen ingestion practices with pubescent boys. In his studies of the Simbari, Herdt describes the people in light of their sexual culture and how their practices shape the masculinity of adolescent Simbari boys.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simbari_people

young Simbari males

Hence for both of the reasons above, I could NOT say how either the ‘passage of time’ or life-events that attain significance in some way to me change my ‘perspective on life’. No doubt when I find an event important it does change something in how I sense the world, comprehend what I sens and feel emotionally about those things bu the changes or changes cannot be the same for each event and the importance I attribute to it. It may just add another perspective on life to my current repertoire rather than creating an entirely new perspective that supplants the old one. It may causes changes that do not endure because they relate to an event whose significance changes. Even if the criterion tested is the ‘passage of time’ there are variations in the kind of time we are talking about – is it just physical and /or mental ageing we are confronting or changes in value systems, such as those which have made fellatio less central to Simbari males in the twenty-first century, or those which re-evaluate attitudes to the relative import of collaborative or individual effort, which have changed so massively in my own life-time, wherein the phrase became current: ‘There is no I in team’.

In many ways I think there is an accumulation of perspectives on life that confuses as one ages, and is often used to excuse shifts of political position that yearn to be seen as ‘natural’ to aging rather than consequences of giving way to self-interest as the most major determination of that position. For me, the truth is, that I am continually surprised by self, other and group interactions together in life, where ideas, feelings and sensations in myself I thought dead revive without warning to be tested for their durability and qualitative strength in their second coming. I don’t think I could, for that reason too, answer this question as it seems to want to be answered. I think the issue is that, for many, stability is over-rated and hence perceived, for that reason of trying to ‘fit in’ with others, over-ready to be perceived where in fact it does not exist at all. I think I may have addressed my beliefs on this in speaking about Naguib Mahfouz’s great novel, Heart of the Night. In Mahfouz there is a coming together of a belief that here is no certainty other than uncertainty in life, a view he took from French existential, and of the importance of not making too distinct a separation between judgements of human statements as either truth or lies, though thankfully NOT in the gross manner of Donald Trump for whom those categories are just inverted for rhetorical purposes. In that blog (available at this link), I quote the main character, Jaafar:

“There is no ‘truth and fiction’, but different kinds of truth that vary depending on the phases of life and the quality of the system that helps us become aware of them. Legends are truths like the truth of nature, mathematics, and history. Each has its spiritual system. …”(Mahfouz op.cit.: 12f)

As I start reading this, I alert myself to label the speaker as a relativist, believing in no absolute truth but only one fitted to the means of explaining and exploring it as in Western Modernist thought, but I think that would not be a correct view of what we have here. Jaafar is not interested in the sum of relative truths, however discordant and fragmented, as Virginia Woolf, T. S. Eliot and James Joyce are in respective modernist works, but in the truths that are visited upon those ‘predisposed to believe ‘ in them by the djinns in which they are being asked to believe. Such truths are not available for all or for all time, because djinns do not stay with anyone Jaafar says for whom their ‘legend’ has been accomplished and is now complete. They disappear at the ‘end of the time of the legend’ and their subject forgets them. If they see them again, if at all, it is only as incarnated in ‘new images of human beings’ where they ‘commit serious evil and cause great harm’ (ibid:15).

And I want to make it clear that reading,reflective or reflexive thinking and feeling, and, writing (which ought to include as an activity both the former categories) are as important, if not more so, than the ‘passage of time’ or ‘significant events in life’ for they are the active agents of any possible change that matters, otherwise a railway sleeper (or other passive and outdating object, would have more to say of endurance and change in the experience of things in the world than any other being, regardless of consciousness or life. If consciousness and life aren’t used, one might as well be, after all, a railway sleeper. Even beauty of form or concept can’t substitute for those absences, for neither are enduring (or durable) ideas – whatever the aesthetes say.

And of one thing I think there are many witnesses: For a starter: Heraclitus, the Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher, Edmund Spenser (courtier to Elizabeth I and Irish colonist, and, Schopenhauer.

The Greek philosopher Heraclitus is credited with the idea that the only constant in life is change. Only fragments of his writings remain, one in which he says:

Everything changes and nothing remains still; and you cannot step twice into the same stream.

Heraclitus’ quote is perhaps best known through its interpretation in the dialogue “Cratylus” by Plato.

Socrates: Heraclitus, I believe, says that all things pass and nothing stays, and comparing existing things to the flow of a river, he says you could not step twice into the same river. (Plato Cratylus 402)

MarciLadd (blogger): available at: https://community.canvaslms.com/t5/The-Product-Blog/The-Only-Constant-Is-Change/ba-p/499288#:~:text=The%20Greek%20philosopher%20Heraclitus%20is,twice%20into%20the%20same%20stream.

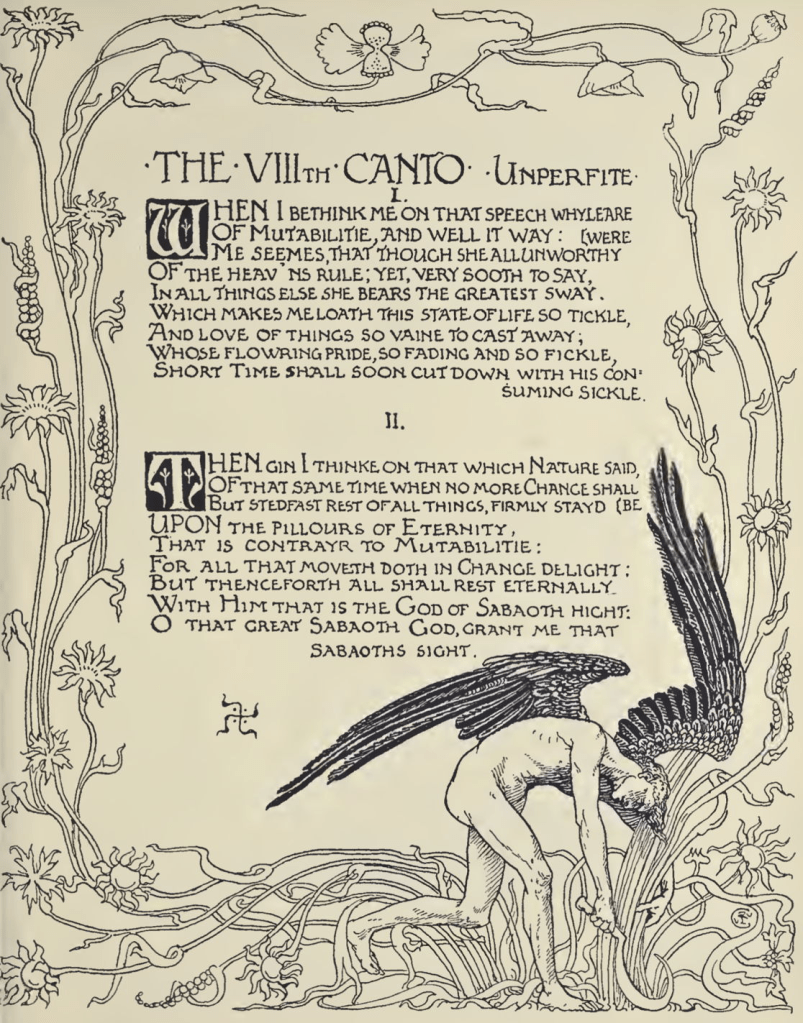

Edmund Spenser ‘The Faerie Queene’ Book VII: ‘The Cantos of Mutabilitie’

All my love

Steven xxxxx