Write about your first name: its meaning, significance, etymology, etc.

An unlikely avatar: Steven Universe, a character by Rebecca Sugar

This is a blog I have resisted because all of the common stories of my name’s origin seem rather strained versions of a thing that is rather common and unremarkable, if ubiquitous. And then there was the problem with its spelling, for a child has to learn the mystery of why the ‘ph’ sound in Stephen might translate by some process into the ‘v’ of Steven. From what seemed to be the beginning of my consciousness of having a name that was distinct and claimed to represent my consciousness and labelled my body, I remember being told at primary school that ‘Steven’ was a ‘lazy’ spelling of Stephen. Did that matter? What follows is my speculation about this question.

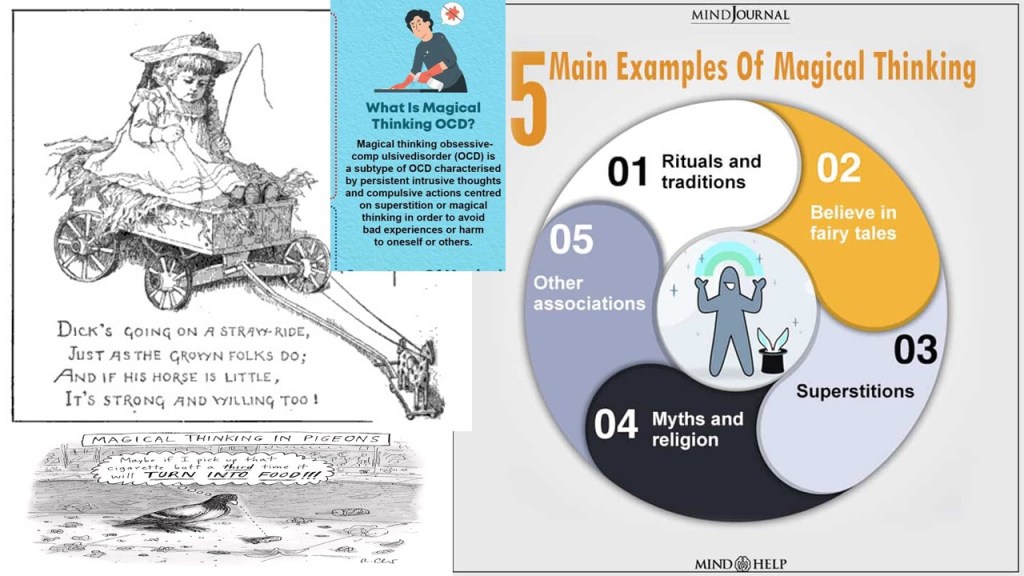

Very young people, I think, weave magic into their names because ‘magical thinking’, as Piaget called it, remains a base tool, not yet relegated to dreams and unsupportable belief-systems alone. It takes time for an infant consciousness to accept that their name, rather than being as inalienably theirs as their bodies, descended on them from a random authority given to parents culturally. Magical thinking probably rejects for some time the view that a name was just projected onto them and hangs on to a felt need that their ‘name’ represents some meaning and significance inherent in their own lives that must, by the evidence of that very need, be something that arises from within the body to eventually possess it and propel it into an outward career in the world.

Hence, this is probably why it troubled me that my name was ‘lazy’. It wasn’t a great help asking my mum and dad, for they joked that, as it was an ‘American’ spelling, it’s gifting to me had to do with the influx of US soldiers after the war.The suppressed idea that I was in fact the son of such a soldier didn’t pass me by as quickly as an adult joke is intended to pass, as ‘only a joke’, for children do ruminate. If the version of my name was either lazy or indicated that this was a family to which I did not belong, neither alternative seemed then to feel positively affirmative. All I remember is the rumination: vague, shadowy and unsure of its status in any significant way as information about me.

Later, I learned, that in fact the spelling variation is based on the difficulty of representing certain consonants in the Greek etymology, and I wonder if this was the first sign of my fascination with the Greek alphabet, for we did not study Greek at Grammar school, though we did Latin that lacked this fascinating picture/ sound difference in its nature as a new language. What Greek I have now comes from using bilingual texts of Greek dramas. But I think that love of the Ancient, and modern, Greek alphabet, attracted me to etymologies and rescued Wikipedia as a source of authority, for it always gives them, after the bashing it got in the academic system in which I once worked at its margins. But Wikipedia is possibly the most democratic access to the use of knowledge in existence, has no paywall and still insists on accuracy by its continually monitoring by its users, even about the ‘trivial’ issue of the etymology of first names. So here it is a bit (at least) of what it says about mine:

The name “Stephen” (and its common variant “Steven”)[1] is derived from Greek Στέφανος (Stéphanos), a first name from the Greek word στέφανος (stéphanos), meaning ‘wreath, crown’ and by extension ‘reward, honor, renown, fame’, from the verb στέφειν (stéphein), ‘to encircle, to wreathe’.[2][3] In Ancient Greece, crowning wreaths (such as laurel wreaths) were given to the winners of contests. Originally, as the verb suggests, the noun had a more general meaning of any “circle”—including a circle of people, a circling wall around a city, and, in its earliest recorded use, the circle of a fight, which is found in the Iliad of Homer.[4]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stephen

Sometimes these prompt questions open up interests I could not have predicted.And here the interest is in the regressive processes of analysis that recreate the evolution of a name. Nothing is clearer in this case than the name derived from a noun of a very basic meaning in early society, a way of labeling a congregation aimed at one central purpose. In each it is a out surrounding something, with the twin features of having a centre on which to focus and a circumference, with an emphasis on the way a relationship between the two is best maintained by a shaping that is rounded not rectangular. Thus a city is surrounded by either a besieging army or its defensive wall, or a fight maintains its interest and duration by taking place within a circumferential audience, serving as witness and barrier.

And because heads are rounded, if not circular headwear, from the ceremonial to the everyday shares this basic concept, a near circle to surround the head. And headwear strains to significance in as far as the person it adorns also must so strain – whether he an athlete receiving laurels for outrunning others in Ancient Olympia, Shakespeare receiving a wreath from a modern king of uncertain status for creating British dram recognised as monumental, or the hubristic commoner elevated as the Emperor Napoleon.

A king must wear a crown, an emperor, or a poet, a wreath of supposedly magical significance. But at base, these symbols are but circular structures to protect the head from the weather or a sword intent on splitting it that has taken on additional meaning. As the Greek word bifurcates into verb and noun, the verb too changes. To circle the head with a protective cover attains the act of wreathing the head of a hero or God with a symbolic material – ok surely, gold or something adorned with symbolic signs.

And maybe , this etymological fancy helps with forenames too. When they were first thought of as Christian names, only in Christian cultures, they tied a mere common human specimen, the son or daughter of someone recorded in their second name or surname, to a individual committed or gifted to God and sometimes from God, as in the notorious Judaeo-Christian case of ‘David’. But saints would do as well as sacred kings or prophets.

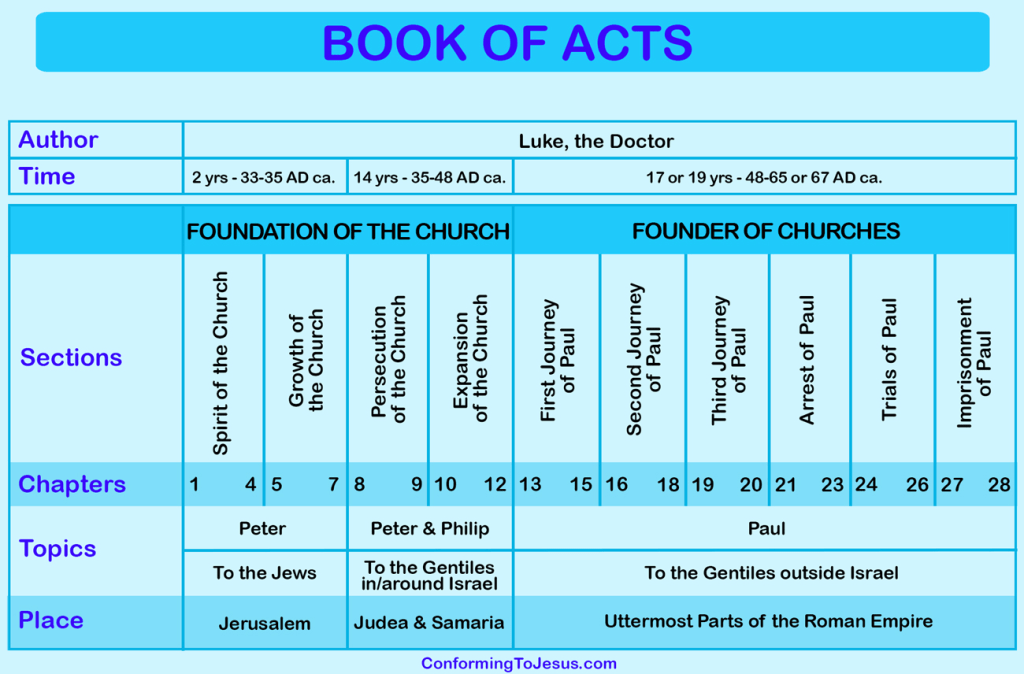

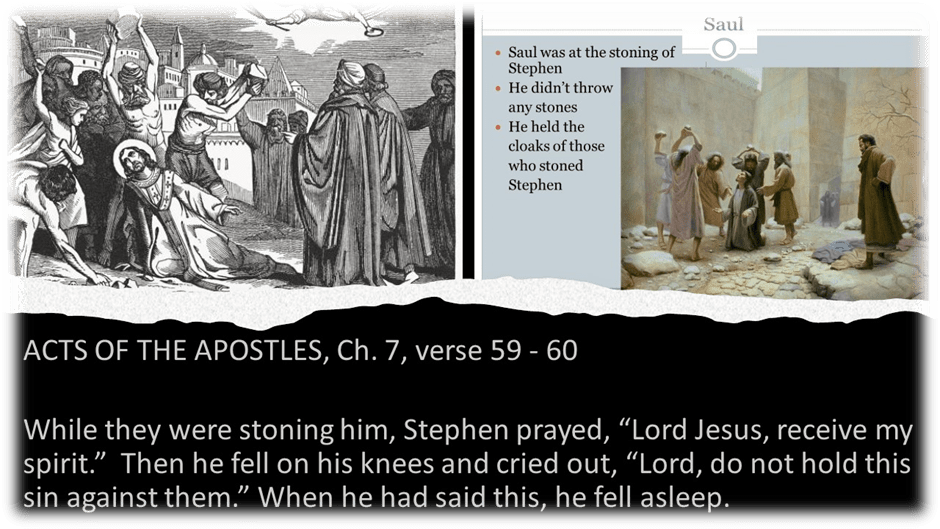

So enter Stephanos, another Greek, whose story is told only in Chapter 6 of The Acts of the Apostles in The New Testament. The story their has a singular purpose it seems,; to establish how well he embraced death by stoning. It’s not even easy to see why he derived death in the eyes either of the non- Hellenes or orthodox Jews. All we are told of his qualities on his selection of a seven-man Christian leadership is that he is “a man full of faith and of the Holy Spirit”, which feels tantamount to saying he hadn’t a single thought he could truly call his own (Acts, 6, 6).

Maybe it is the reticence of the Bible after the death of Christ that we don’t hear either the substance of the ‘great wonders and signs among the people’ (Acts, 6, 8) that he perpetrated other than talk big to people with whom he disagreed. Even these disputants had to resort to lying to make Stephen look like a significant threat: “they secretly instigated men, who said, “We have heard him speak blasphemous words against Moses and God, ” and lots of other unlikely fictions (Acts 6, 11f.). And thence to the nub of the story. Men surround Stephen (in a circle perhaps) once they have thrust him out of the city and stone him, wondering why, perhaps, as they do so, he seems to think and declare they are doing him a favour and leading him all the quicker to the glory of Paradise. Saul, a Jewish functionary then but later to become Saint Paul, was present at Stephen’s stoning.

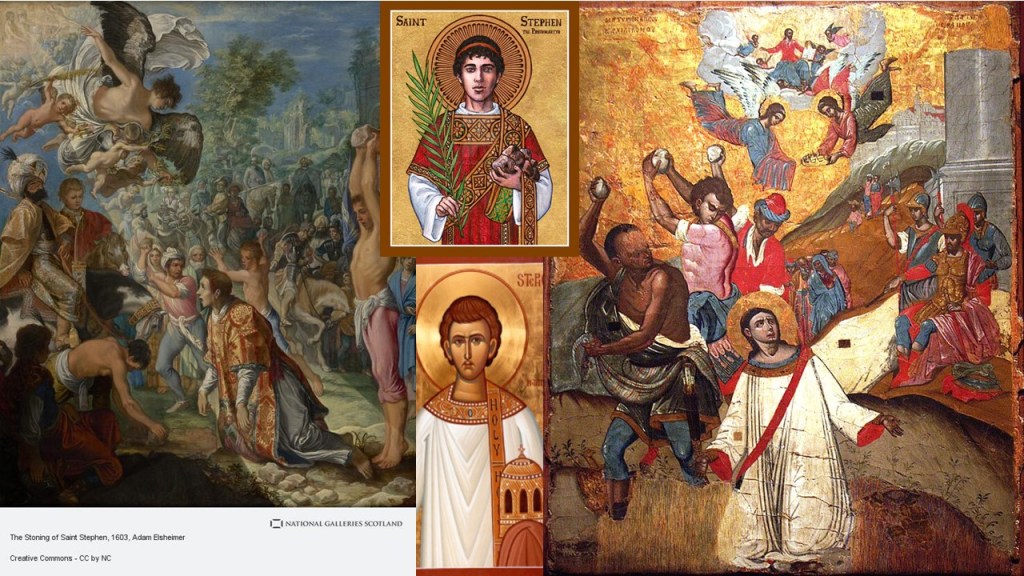

If nothing became Stephen in his life more than how he left it, then we have I think to then go on to see how the meaning of that act of, as it were, choosing death rather than submit to enemies was elaborated. And then comes the issue. Stephen is venerated as the first Christian martyr, the protomartyr. That status in death was elaborated in art by the iconography that is associated with him. Here is the basic description of it in Wikipedia.

Artistic representations often show Stephen with a crown symbolising martyrdom, three stones, martyr’s palm frond, censer, and often holding a miniature church building. Stephen is often shown as a young, beardless man with a tonsure, wearing a deacon’s vestments.

The meanings are clear. Death in defence of the Church or something that could be elaborated as such is a sufficient cause of glory. Hence, Stephen is dressed in a lowly clerical order and as a man not yet mature enough For significant Acts other than death in his life, and bearing not a means of increasing his own value but the representational virtue of the Church as an institution, in that huge scale model of it he carries around. But something is intriguing here. A martyr, especially the very first, wins a ‘crown’ or ‘wreath’. Suddenly etymologists everywhere grow alert. Was Stephen the name of this man or do saints, like pope’s on their enthronement, get to choose their names to which in stories of their early and pre-canonical life they will be referred to?

After all a version of this exists in the transformation of the Jewish Saul becoming Paul in the archetypal story of why Christian names replaced forenames within the Christian tradition. Is Stephen really only the circular band of ethereal material he is thought to wear in Heaven, a simple ‘circle’ round his head that strains to eternal and weighty significance as a ‘martyr’s crown’ gifted by God playing the role of an early Emperor or King, giving gifts to his loyalist followers.

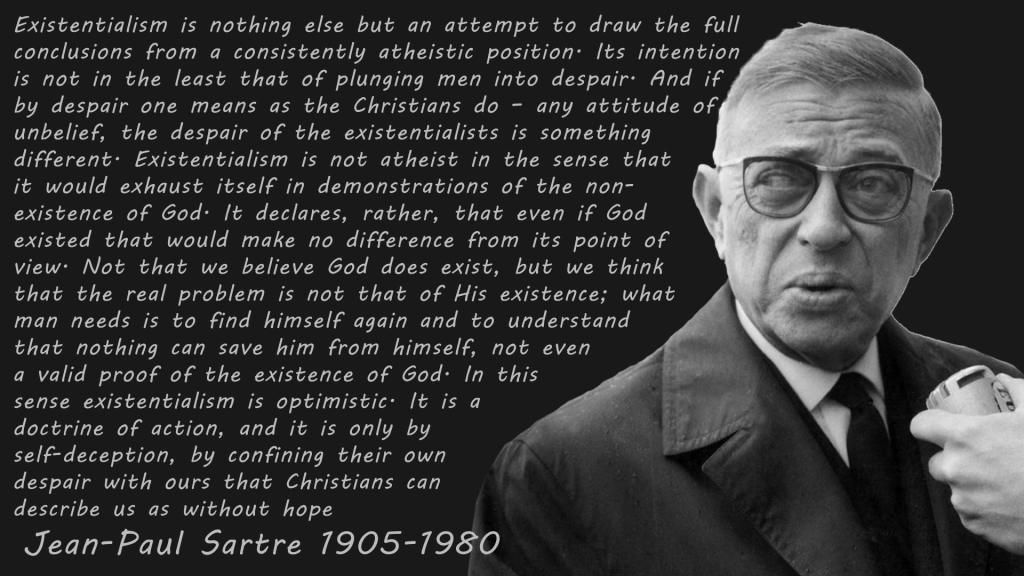

So starts a story of parents bestowing names on their children whose original meaning is eventually forgotten. And in this happenstance, I think I trace my birth and christening in a society that no longer truly venerated the reason such names were apparently needed. For mythologies of individual greatness – whether ornamental as in crowns or wreaths – or as a memorial to a significant act, such as Stephen’s joyful acceptance of his stoning to death and the personal.pain that involved, are examples of the magical thinking that belief systems like religion or sorcery impose on a life that is felt otherwise to be, as the Existentialists thought they discovered, a Nothingness’, or better, in Sartre’s term in French , ‘le néant ‘ (Not-being’, void).

And this reminds us that children do not lose magical thinking, they store it mentally. Jung thought they did so in Archetypes that had validity in themselves independent of the socio-psycho-cultural circumstances that were the probable sources of the immediate meaning contingent to it, as Freud, a much wiser mam though that is rarely admitted, showed us. Would non-elitist cultures really values fabricated circles you put on your head or wreathe great minds with them in the statuary or painted images of their bodies: even ‘commoners’ like Shakespeare, or functionaries like Chaucer (in the insulting form ‘Dan Chaucer’ the Sir Edmund Spenser liked to name his great predecessor as).

And as this revolved in my head, a synapse burst surprised me for ‘circles’, the possible humble origin of all Stevens and Stephens are actually the very stuff of magical thinking, suggested by this paragraph on circle symbolism:

The circle signifies many sacred and spiritual concepts, including unity, infinity, wholeness, the universe, divinity, balance, stability and perfection, among others. Such concepts have been conveyed in cultures worldwide through the use of symbols, for example, a compass, a halo, … rainbow, mandalas, rose windows and so forth.[10] Magic circles are part of some traditions of Western esotericism.

This kind of generalised symbolism appealed to the revival of interest in the literally creative powers of imagination, as Europe emerged from the Age of Reason, which had after all plenty of its own divergences from what is reasonable, and circles are important in Romantic art in all its forms, as suggesting the ethereal and sublime, and possibly the problematic – for creative thinkers become a problem, the archetype being Goethe’s version of Faust.But the real synapse burst was of lines from Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Kubla Khan that connect not only to circles but the etymological link of the name ‘Steven’ (as a verb) to acts of wreathing and weaving intricate circles. The lyric voice in Kubla Khan becomes obsessed with the idea that to see things that are not there, to imagine, is akin to the dangers associated with magic, or, at the least, will be seen as such by those not so ‘blessed’ (or ‘cursed’) with a desire for an ‘otherworld’ – a ‘pleasure dome’ or earthy paradise’ – that it is normal to give up on as magical thinking disappears into what is called adult maturity and the willingness to see such dreams as either unavailable or chimerical. As the lyric voice realises his lyric is inadequate in comparison with those that match his vision of perfection of sensate pleasure that the songs sung there invoke:

Could I revive within me

Her symphony and song,

To such a deep delight ’twould win me,

That with music loud and long,

I would build that dome in air,

That sunny dome! those caves of ice!

And all who heard should see them there,

And all should cry, Beware! Beware!

His flashing eyes, his floating hair!

Weave a circle round him thrice,

And close your eyes with holy dread,

For he on honey-dew hath fed,

And drunk the milk of Paradise.

And the lost voice of this dreamer wonders if the price of such a vision of perfection might be alienation from the world. For the man claiming a special nature (one not based in worth validated as it had always been by privileges of birth in person or patronage of those capable of serving your need for the imagined, and his magical self-elevation to the air will be met by fear of his ‘flashing eyes, his floating hair’. And what will they do. They will: ‘Weave a circle round him thrice’ and refuse to look at him, for he looks tainted with the queerly special, with that magic that is hard to substantiate but definitively looks mad , whether it be magic, talent or insanity, anyway something very separate from the norm, something deeply ‘queer’. ‘Weave a circle reminds one of the etymology of Stephen and the cost to Saint Stephen of his name (a martyr’s crown): ‘that is a first name from the Greek word στέφανος (stéphanos), meaning ‘wreath, crown’ and by extension ‘reward, honor, renown, fame’, from the verb στέφειν (stéphein), ‘to encircle, to wreathe’.[2][3] In Ancient Greece, crowning wreaths (such as laurel wreaths) were given to the winners of contests’. Earlier of course it just meant ‘circle’ and nothing more, but as poets take on airs and elevation that is simultaneously spiritual and embodied (so Coleridge at least thinks in the most magical thinking of which he was capable, stuffed as he was with the theories of Ancient Neo-Platonism and their circles – even the ouroboros (snake with its tail in its mouth which he, and Shelley later, saw as the symbol of the creative imagination)the woven circle is the weaving of significance around a central thing that may in itself and without that process have any meaning at all – like Saint Stephen with a church in which no-one believes any longer.

So what to conclude – that Samuel Coleridge might rather have been called ‘Steven’? No! But that the search for meaning in one’s first name is at a means of trying to make special what is entirely circumstantial in its meanings, even if it takes looking over the whole Longue durée of its genesis and uses during it to find that out. And the name Steven is the archetype of this, for its meaning is fairly humble until it is elaborated into metaphor and special models of its use (like Saint Stephen).

I rest my case.

With all love

Steven xxxxxx

As usual, thought provoking and interesting, ensuring that I further check things that it had never entered my head previously to consider. Thank you for this. As a Karen I have seen my name change from being the most boringly common (I was named when it seems every third girl child was given the name Karen, with at least three of them always being in the same class as me at school) to it transforming into an all encompassing term of abuse indicating a particularly loathed stereotype.

LikeLike

All love to you Kes,

LikeLike