If you could un-invent something, what would it be?

Un-invention is, like invention, a means of realising through thought and work some solution or respite, pragmatic, and perhaps temporary, though it may be, to ones currently unmet desires or the dread of anticipated fears. We un-invent in order to pretend something never existed: the ending of some relationships (and not just in divorces, is like that. Suddenly what we thought was an answer to our desires, or a bulwark against our fears, no longer is so. For many that involves not only the need to change or kill that relationship in the future but to undermine its right to have existence in the past.

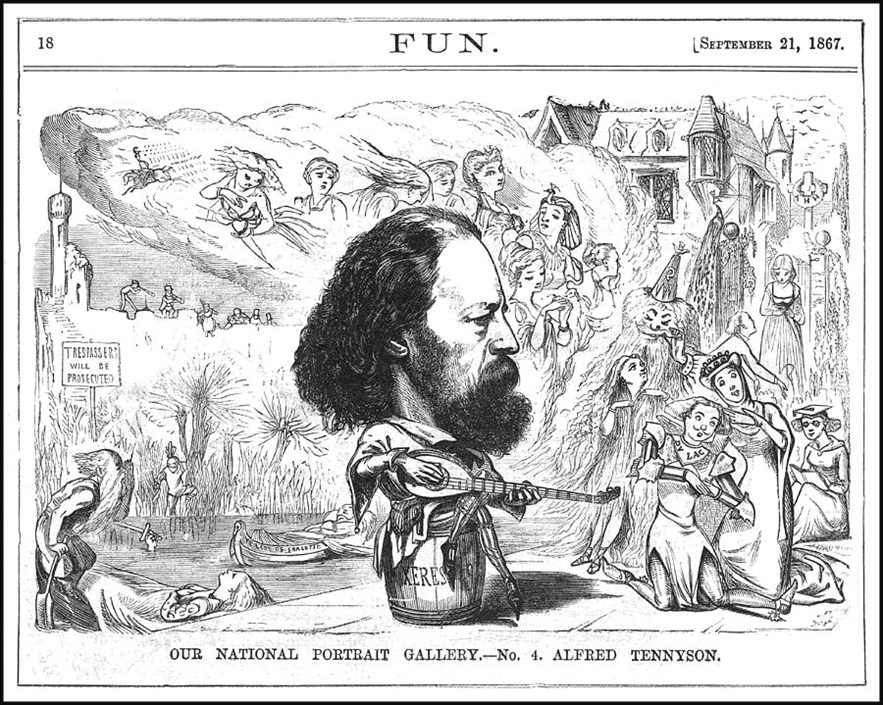

Tennyson is always there want you want him, to express life at the level of one’s desires and fears

Be near me when my light is low,

When the blood creeps, and the nerves prick

And tingle; and the heart is sick,

And all the wheels of Being slow.Be near me when the sensuous frame

Is rack’d with pangs that conquer trust;

And Time, a maniac scattering dust,

And Life, a Fury slinging flame.Be near me when my faith is dry,

And men the flies of latter spring,

That lay their eggs, and sting and sing

And weave their petty cells and die.Be near me when I fade away,

Alfred Tennyson Lyric 50, ‘In Memoria’ at: https://victorianweb.org/authors/tennyson/im/50.html

To point the term of human strife,

And on the low dark verge of life

The twilight of eternal day.

This poem is perhaps the greatest example of a desire for proximity or presence that barely needs giving identity, except that it must be some compensation for the failure of the promise one once felt to be present in life. At such times all we have of life is the insistent record on the senses of its near absence. It is sensation and feeling that is viscerally so strong, over a duration and intensity of sensation that feels unbearable, that only the most extreme of metaphors will do to tell how the passage of time and the signs of life tell on the consciousness that is reluctant to engage them. The body is so sick and every mechanism of life running so slow that the otherwise wanted attentions of men are like insects that you abhor and come too late, to impregnate only the flesh dying off slowly around you with their ‘eggs’. Abstract categories to describe human experience like Time and Life, are of monstrous and insane figures, with no real embodied reality – only frenetic action that aims to speed one’s destruction as it slows your resistance to their vague attack. I am not sure ‘eternal day’ is yet to come, for this seems an evening twilight not a dawn half-light, and something eternal ought not to have such cusps of beginning and ending. And the real victim of such processes is, Tennyson make quite clear, the capacity of human beings to ‘trust: and perhaps the lack of trust is to each other, oneself, some view of guiding Providence for the whole of your group or a combination of all of these.

The line I cite in my title kept singing through my head as I read Labatut’s novel. And this may not be just because of the novel’s title which refers to the first thinking machine to make claims of a potential for demonstrating general intelligence – intelligence applied across a range of areas of interaction with another or others, or a problem requiring solution, rather than confined to excellence in one field of activity. My belief is that this lyric sings through my head because the novel too is about the desire for humans to trust their own humanity and to resist fears of its total demise: ‘the pangs that conquer trust’ in Tennyson’s words.

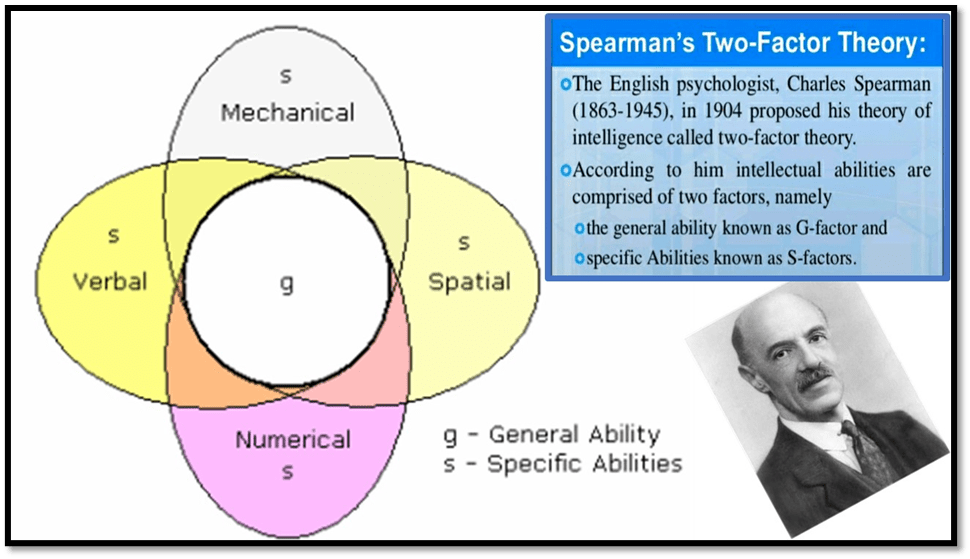

The concept of general intelligence was devised in the first bloom of the desire to make rankings of ‘intelligence’ a meaningful way of explain individual differences between people across the ‘whole’ range of tasks imagined by psychologists to whom these differences mattered – often psychologists serving divisive hierarchical models of education or access to employment or to right of entry to a country. Indeed as late as 2020 Jason Richwine was appointed to a high post in immigration control in the USA on the strength of public beliefs, first that immigration was a drain on ‘native’ US resources and that, if it happen at all, it should happen only on the basis of relative IQ, with only high scores allowing potential entry. This is disturbing, particularly in the light of some attempts online to exonerate the tests of immigrants on Ellis Island for feeble-mindedness that the intelligence engineers did not wish to bred into US populations, lover average nation ‘general intelligence’ (read a quick summary of debates here).

Artificial Intelligence is a wide-ranging concept and some uses of it apply only to the building of algorithms that can run with the intention of increasing the speed, efficacy and efficiency, in the performance of a SPECIFIC task. Of course, if those asks require decision-making, then we need algorithms that measure against each the# different criteria for those decisions, and this usually involves some work across multiple specific areas of measures for those criteria. There is something like then ‘general intelligence’ required in some decisions, but it is not clear that this is absolutely necessary.

But let’s consider what the consequences would be if we were to decide who we can allow access to our nation, employment in an enterprise, or educational opportunity we identify our own interests with, by virtue of an assessment of a g-factor, like IQ. One consequence is the strengthening of an assumption that variable capacity of measuring trust in others general intelligence, across a range of factors, exists for only that assumption would justify a search for a program that will instantiate those decisions of trust at their highest level. The corollary of such a ‘machine’ (let’s use this inaccurate term) being recognised to exist is that it proves the variability of human qualities over hierarchical layers of trustworthy decision-making about human trustworthiness.

In effect, the dream of an achieved AI that assumes AI’s greater capacity of ‘general intelligence’ should frighten us because it reduces the meaning of our humanity to something that is not shared equally, and which allows for distinctions of what is the best of humanity on a scale down to the very worst sub-division of humanity. If that is the case then lower ranges on such a scale are, under pressure of competition for resources, seen as less eligible for those resources than upper divisions – they are perceptible as a kind of lower humanity. This expressed as an unresolved fear and desire about human social perfectibility is apparent in HG. Wells The Time Machine and the picture of a society divided between Eloi and Morlocks, wherein Well’s ‘scientific socialism’ seems to have the potential to Fascism, though this is not the only reading of the story.

These are the feelings I had whilst reading Labatut’s extraordinary novel The MANIAC, wherein MANIAC is the name of the candidate for AI supercomputer status used by the person who is the focus of the central parts of the collaged stories in this novel, John von Neumann.

Labatut’s novel, though it is a fictionalised reading of the life of von Neumann, from many narrative perspectives (friends, family, colleagues and rivals, both academic and those working with him in the technologies derived from them) also includes reference to giants in the real history of science like Alan Turing, Albert Einstein, and, of course, Oppenheimer with whom he worked at Los Alamos. And yet the novel is also a set of stories of novel ideas as well as ‘inventions’ (machines and their encoded operating systems and algorithms). But at base, and why it excites me as a novel, it is about grand metaphysical abstractions as they impinge on human imagination, even reflexively in being about how unknowable analogues of human imagination as a mode of thought, feeling and sensation is created in and in the aura of the visible and invisible stuff that is AI.

It ends by showing how impenetrable remains the victory of Alpha-Go in a series of five separate games of Go with the world’s acknowledged expert in the game so far, Lee Sedol, bur begins with the case of the ‘pure’ mathematician, Paul Ehrenfest, that genius whose depression became one of the bases (another was the threat of Hitler to intellectual Jews and the mentally unstable) turned murder of his own son with Downs syndrome before committing suicide. In both cases reason and madness play upon the cusp of the imaginative interpretation of actions. The origins of Paul’s ‘death wish’ is the fascinating driver of the novel thereafter, and in a novel that features the supercomputer system MANIAC (the acronym of the Mathematical Analyzer, Numerical Integrator and Computer) any readers eyes prick up when they read of his sense of wasted life and ambitions which accompanies Paul’s dread of the new mathematical physics of von Neumann that he called, the ‘mathematical plague that erases all powers of the imagination’.[1] This sense of defeat of everything he valued in a notion of creative humanity is equated by Labatut as a ‘death wish’ embodied too in his lover, Nelly and their common drive in the ‘rediscovery of the irrational’ that they thought be the ‘the driving force behind all vanguard movements … suffused with a Faustian boundless energy, a haste, a tragic gall in which everything was permitted’. It is a force that just a little later will be described as ‘his mania’.[2]

Yet contemporaries too saw him as a kind of Faust, implicit in the invention he wanted the end of – even spoofed him in that role in a semi-jokey ‘skit’ of the Faust story, in which he was Faust (not cited by Labatut though Faust is).

I have–alas–learned Valence Chemistry,

Theory of Groups, and the Electric Field,

And Transformation Theory as revealed

by Sophus Lie in eighteen-ninety-three.

Yet here I stand, for all my lore,

No wiser than I was before.[3]

Lee Sedol, in defeat by AlphaGo, the son of sons of MANIAC, does not become manic, although the classic symptoms of bipolar depression never seem far off from being described, but he is not beaten by AI but ‘crushed’ by it: “With the debut of AI, I’ve realized that … Even if I become the best that the world has ever known, there is an entity that cannot be defeated”.[4] Ehrenfest has no empathy with AI, he is near as we get, though Einstein too calls it in the novel a ‘dark unconscious force’, to a wish for its destruction before it leads on the Apocalypses that it at the edge of its corollary theorem of game theory, Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD). He calls the elements that become AI, ;a profoundly inhuman form of intelligence that was completely indifferent to mankind’s deepest needs’.[5]

In the middle of these different kinds of mania and depression, lies János Lajos Neumann, who if the novel likes to slyly Paul Ehrenfest as Faust, presents him, later to be John ) or Johnny) von Neuman in order to both democratise AND ‘aristocratise his ordinary Hungarian name in the Germanic “von”’ his name for his own reasons. He becomes the embodiment of his own ideas and those he steals from others ad is definitively this ur-Faust novel’s Mephistopheles, or even Lucifer himself. As a boy he is described by a schoolfriend who moves through the whole story, Eugene Wigner, as ‘alien’, ‘something completely Other’, and even ‘luciferin’ (an elegant term from descriptive physics with a useful association).[6] His younger brother remembers his attachment to machines as if János would be something he could ‘ride atop, like a Mongol conqueror at the head of his horde’.[7]

Faust and Mephistopheles

The fictive version of Gábor Szegő actually, unwittingly or not describes Lucifer in opening his account of his friend. Both were Hungarian Jews and both mathematicians, yet to Gábor, Neumann is a ‘little devil, that one, but also an angel to those of us who saw the madness that was coming and fled from Germany before it was too late’.[8] Although he assesses him as ‘incredibly shallow’, he also sees his leadership of a form of mathematical logicas something that fitted itself into a ‘god-shaped hole’, and, indeed Von Neumann will, in the course of the novel, use his work to compare and reinvent the notion of human consciousness in the light of what he sees as an underlying ‘machinery’ of neural connection and, eventually as he dies of cancer, God himself.

The words that von Neumann takes as his own in this quest are those I mentioned in my opening – basic human needs like a ‘trust’ and a ‘faith’ in the potentials of best self, others and perhaps even of Creation and a Creator – God or gods. A progenitor, Hilbert, we are told also like Neumann represented the ‘symptom of the time, a desperate attempt to find security in a world that was running out of control’ and finding it in the ‘sanctity of the queen of natural sciences. What else could we put our trust in?’[9] Is this the same ‘queen’ envisioned by the mystic Hadewijch of Brabant cited in this novel’s starting epigram, who is ‘my soul’s faculty of reason’, whether it be so in fact or in an alchemical chimera. We are very near here to the words of Tennyson I started with:

Be near me when the sensuous frame

Is rack’d with pangs that conquer trust;

And Time, a maniac scattering dust,

And Life, a Fury slinging flame.

And we are near too to the madness of the Gods whose self-destruction, as in Norse myth of Ragnarök, will be as magnificent (if not more so) than creation, as time and life impel their own MUTUALLY ASSURED DESTRUCTION (MAD as that is). And for Neumann, this was the sequel of a mechanism of mathematical logic, and the logic gates of computing, that can and WILL do anything, however irrational except in a paradigm of ‘reason’ where it must be assumed, as in ‘game theory’ as it was then, that participants in games are each ‘based on two sets of interests diametrically opposed’, as reason and imagination as creative forces were becoming through Neumann and others. The genius of DeepMind that becomes Lee Sodol’s true antagonist, the scientist Demis Hassibis, whose goal, as cited in the novel, is “investigating imagination as a process”.[10]

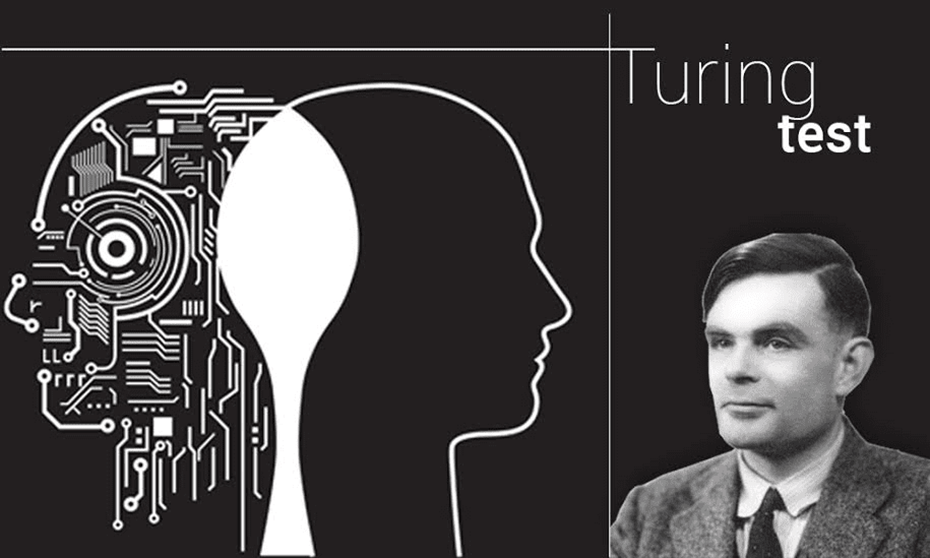

In this novel there is a kind ghost who, though often compared to Neumann in it, by Hassibis for instance, as his 1950s progenitors, is not the maniac that others are – Alan Turing. For Turing still looks, as others in this book discuss him at least, for an AI that is totally reconcilable to humanity, a human child capable of ‘not only error and of deviation from their original programming, but also of random and even nonsensical behaviour’.[11] The problem of the novel is that this exactly describes the triumphant AlphaGo which defeats Sedol. The only difference is that AlphaGo completes tasks in a SPECIFIC domain that of the games of chess and Go, it has not yet found its way to become GENERAL INTELLIGENCE (based on binary assumptions of a right and wrong, good and evil totally in opposition to each other), the dream of the 1950s in America and of game-theory in particular.

Yet we need,as the novel demonstrates, to return to the examples of the maniacal energy of the 1050s AI inventors and their belief in a foundational general intelligence,. Examples are the stories of Moritz Cantor’s work achievement as described by Henri Poincaré: “un beau cas pathologique’ (a beautiful case of madness), or the assessment made about Kurt Gödel, that his ‘particular form of paranoia was not just the cause of his downfall, but also lay at the root of his incredible mathematical achievements’.[12] Neumann is described by Szegő with the full rhetoric reserved for stereotypes of insanity in his representation here: ‘Cackling maniacally’ in a restaurant with Szegő. He is described with the word that describes system of realized mathematical logic: MANIAC.[13] And I will insist that what requires uninventing, is not a machine or code but a view that ought really to have already passed away in scientific psychology; that of an AI of ‘general’ not ‘specific’ and task-based intelligence. In one of the brief inter-chapter notes this is called Neumann’s ‘second goal’, which was ‘to create a new kind of life’.[14]

The first goal is described in the preceding inter-chapter note, not by a character but the authorial narrator: ‘to destroy life as we know it’. This accusation makes Neumann the twentieth-century’s Dr. Frankenstein, as understood by Mary Shelley in the nineteenth century. Although first descriptive of Nils Aall Barricelli, this aspect of their collaborative work seems based, rhetorically at least, on a set of almost shamanic ideas associated with the character representing Barricelli, who speaks of invention in computation as the creation of life from fragments : ‘the birth of something new. … that sudden glimpse of the future’ but something ‘not bestowed on me by the gods.’

It was given by that new deity, the one we worship before with bowed heads and look down upon with glazed eyes: my pythoness was a computer. And deserving of my faith indeed’.[15]

Yet in this fictional account, Neumann becomes increasingly the true Dr. Frankenstein, a scientist who becomes incapable of deserving human trust, even Barricelli’s. He works in the laboratory at the ‘middle of the night’ with his collaborator on something that in Barricelli’s imagined words are still ‘ephemeral creatures’ of imagination but ‘locked in solid memory, trapped within the confines of materials so utterly coarse and counter to their nature that to think of it curdles my blood’.[16] This is the stuff of horror writing and those ‘coarse materials’ remind one of the bits of once embodied beings brought to science for revival from their graves. Though it is Baricelli that says this in the novel, the latter becomes entranced and pushed into the background by Neumann’s diabolism, his ability to have ‘snaked into my lab without notice’ (like Milton’s Lucifer) and Barricelli has to become ‘as quiet as a dormouse’.[17]

It is strange that simile, for the Julian Bigelow character in the novel has already told us that Barricelli had a ‘little rodent face’ and that eventually: ‘Nobody took him seriously’, after the rift with Neumann.[18] Moreover in an earlier contribution Bigelow recounts a story of MANAC’s predecessor, ENIAC, into which ‘a mouse crawled .. once’ and, after chewing wires ‘was burned to a crisp’.

We rescued the machine but never managed to get rid of the stench.

It always smelled of charred meat,

Singed hair, and burned whiskers.

Poor Baricelli

You may by now see clearly that I have long despised that principle of knowledge called positivism that pretends to be the sole acceptable framework of ‘scientific’ thinking based on the notion of the empirical alone – which equates to modelling truths in experiments or created manifestations of the operation to be demonstrated (like computer models). The key principles of these – and they are those required to make ‘general intelligence’ work as a measure of one kind of human worth – are those of statistically reliable and valid prediction, and the conditions of CONTROL, under which alone, those predictions can be borne out. How near to Neumann, in the novel at the least, this is. We can cite this statement, supposedly of his wife Klára Dan, who in describing his attempt to build a model of weather prediction, evokes his faith in computer modelling of phenomena (see the quotation in my collage on Neumann too above):

His optimism that we could accurately predict the weather was entirely based on the capabilities provided by computers such as his MANIAC: “All processes that are stable we shall predict. All processes that are unstable we shall control, …”.[19]

The same confidence speaks too in another quotation chosen to fit between chapters, which look like this photograph of pages 176 – 177:

This is such a rich book. I loved it despite myself for it is truly science fiction rather science fantasy, as in H.G. Wells and others. But the point of this blog ostensibly is to say whether one can uninvent AI, or more strictly, a conception of AI that equates it with the concept of ‘general intelligence’ that early theorists, including eugenicists, believe to be fundamental to discrimination (positive or negative) between the thinking of variable species and within single species (such as humans). These value judgements are the most dangerous ways in which this view manifests itself. It is how it was used in Ellis Island in early USA immigration, and may yet be again in the UK and USA if we fail to abandon the most rabid form of Toryism now ruling over us in the UK and attempting to trump its way back in the USA. It relies on a view of naturally validated hierarchies between and within species that ignore environmental factors, even in some interaction with biology. It is the view underlying, this apparently innocent speculation of the character based on Eugene Wigner:

I have often wondered about the consciousness of animals, how it must be more shadowy than ours, more dreamlike and fleeting, small thoughts like half-burned candles, their outlines never fully formed. And perhaps that is also the case for many of us who strain to think with clarity. I have known a great many intelligent people in my life. … But none of them had a mind as quick and acute as Janos von Neumann. …/ Only he was fully awake.[20]

That is beautiful writing of Labatut’s in his debut novel that is originally written in English (surely a Booker contender) but it is chilling when you think about its meaning, for its described gradations of intelligence oft become the basis of decisions that regress to eugenics in one form of unnatural selection or another. It is at the root of TERF and sociobiological thinking, and Labatut is clearly anticipating the later work of Wigner, summarised thus in Wikipedia, which tries to see the mind as little more than a highly determined algorithm that varies in ways that are not controllable other than by exclusion of the unworthy. And what is unworthy are minds ‘more shadowy than ours’, which in various cultures at the time was assumed to be the racially ‘inferior’, women, the insane and ‘feebleminded’:

Near the end of his life, Wigner’s thoughts turned more philosophical. In 1960, he published a now classic article on the philosophy of mathematics and of physics, which has become his best-known work outside technical mathematics and physics, “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences“.[52] He argued that biology and cognition could be the origin of physical concepts, as we humans perceive them, and that the happy coincidence that mathematics and physics were so well matched, seemed to be “unreasonable” and hard to explain.[21]

Now, I have to admit, that though I have loved writing this, I feel too tired to check it yet for errors and poor writing (examples of which are probably legion) and which may, anyway appeal to very few. But I think Labatut has a mission to make us see that we ignore the ideological reflections of certain ways of conducting science at our peril. So many of his characters, based on history and close research thereinto, are Jewish and the Götterdämmerung of the Holocaust hangs over this novel, as a period where such signals that science was sending out were ignored in terms of their failures of a test of humanity. Turing’s version of such a test alone shows how naïve very great minds can be. He became one of the victims of such innocent naivety as a queer man, for he saw the forces against him as human rather than ideological (and literally monster-making) and therefore could only see a future in taking his own life.

Well, the choice is yours. Either judge this as a response to Bloganuary or read the book. Personally I am going to get Labatut’s first book (in translation) on my Kindle.

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Benjamín Labatut (2023: 10) ‘The MANIAC’, London, The Pushkin Press.

[2] Ibid: 13, 15 & 21 respectively

[3] Cited by the American Institute of Physics’ Society of Physics Students in a review of a biography of Ehrenfest in Winter 2013 available at: https://www.spsnational.org/the-sps-observer/winter/2013/struggles-paul-ehrenfest

[4] Labatut 2023 op.cit: 350

[5] Ibid: 22

[6] Ibid: 49 & 47 respectively

[7] Ibid: 62

[8] Ibid: 84

[9] Ibid: 76

[10] Ibid: 292

[11] Ibid: 191

[12] Ibid: 79 & 100 respectively.

[13] Ibid: 89

[14] Ibid: 173

[15] Ibid: 197

[16] Ibid: 196

[17] Ibid: 200

[18] Ibid: 181

[19] Ibid: 213

[20] Ibid: 54