Book into Film: Alasdair Gray’s (1992) Poor Things: Episodes from the Early Life of Archibald McCandless M.D., Scottish Public Health Officer Edited by Alasdair Gray and Poor Things, a film directed by Yorgos Lanthimos with screenplay by Tony McNamara (The Favourite). A series of reflections on seeing the film on 15th January 2024 at the Odeon, Durham.

This is blog number 3 in a series of 3 on Poor Things:

Number 3 of 3. Book into film: Truth, lies and ‘Poor Things’

For No. I in this series: Book into film: Setting ‘Poor Things’ (use the link)

For No. 2 in this series: Book into film: Queering ‘Poor Things’ (use the link)

The final blog of this series looks at how both ethical and academic concerns about truth-telling and evidence-based accounts and the distinction made in the telling of stories, and especially histories, between what is factual and what fictional in that telling. In a common-sense view of history, the two concerns may seem to be one, for it is assumed that both understanding and actions based on that understanding requires that the thing understood is true and demonstrably based in established fact. Yet historians continue to debate various forms of relative truth in their subject, where what is considered factual might vary according to the interests involved in each of several different accounts or on frameworks or paradigms through which the truth is filtered from the foundational truths, considered unprovable and not requiring such proof, to other belief-systems or acceptable myths. Certainly, the way agents in history act is unlikely to be understood without allowance for some basis of those actions in things we feel uncomfortable asking everyone to agree to be facts, such as the biological basis of abstract differences between people like intelligence, beauty and even issues like class or sex/gender, where the facts that establish such categories remain contentious even sometimes in knowing the domain in which they are finally to be judged as knowable.

In art, a further distinction is sometimes used between what is artifice and what is natural, that involves even greater differences of emphasis on notions of the nature of creation and the created in the frameworks for understanding what is ‘natural’.

All of these concerns lie on the surface of texts that record multiple stories from multiple points of view like Alasdair Gray’s Poor Things. After all, it concerns itself with the cusp between science, as an attempt to know things like anatomy, and technologies through which such knowledge is used to make or create things, such as ‘the queer rabbits’ mentioned in blog 2 where McCandless urges these things were more of ‘art than nature’. This concern runs through various chapters in which the term ‘making’ is use in different ways – in determining for instance how someone is made to be the way they are, as in the chapter 1 ‘Making Me’ about how McCandless is made a gentleman from the raw material of ‘farm workers’ or Chapter 2 ‘Making Godwin Baxter’ about the cutting out of the disabled scientist by his abusive knighted ‘progenitor’, Sir Colin. In both cases making is about how these men are created from the raw materials of a boy. It becomes more complex, if related ideologically and symbolically, in Chapter 5, ‘Making of Bella’, where the raw materials are initially inanimate. Both senses of making are used frequently of Bella and the agencies of her being such as in chapter 14 with the sub-title of ‘Making a conscience’ or Chapter 12, ‘Making a Maniac’ where Duncan Wedderburn is ‘made’ mad. At some other times, the word is used loosely as in the manner of Wedderburn ‘making’ Bella, by which is understood, making her ‘a woman’ by having sex evaluated entirely by their sex/gender and genital difference.

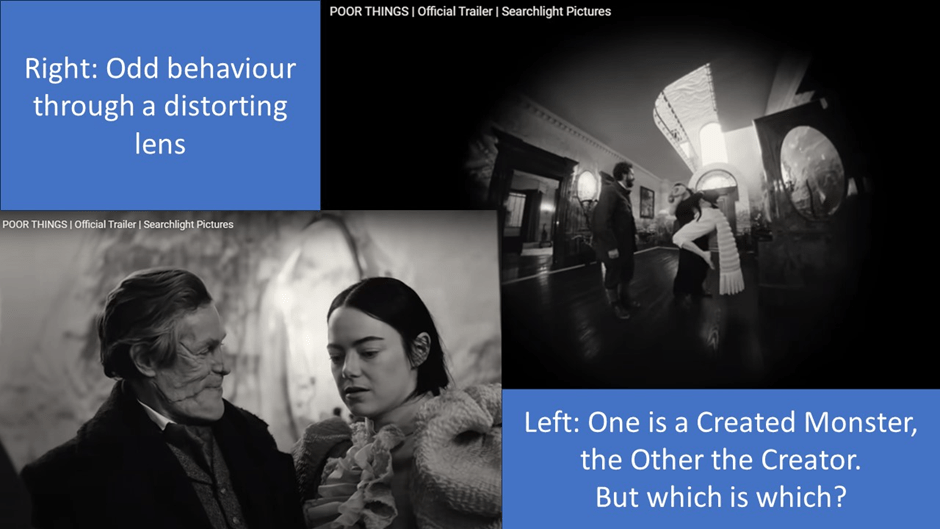

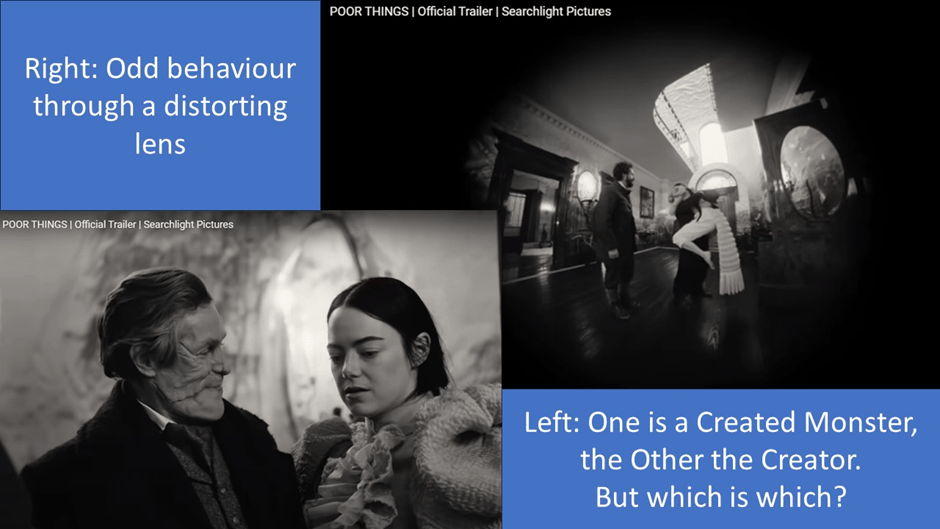

We only need to ask the question, ‘how is Bella made’ to realise the answers are legion and imply agencies of fact and faction, art and nature, and, of course, truth and lies. This is more he case if we take into account the processes of storytelling itself which must create a character in the retelling, reproduction or enactment. It is a matter for storytelling that involves however many agencies that is require by an art form, whether it be an oral story, privately written account, major publication or film. The making of monsters is such a trope of film that Lanthimos in Poor Things film can refer back to this trope merely by the setting, properties, costume and ‘make-up’ of certain scenarios:

Hence, both artworks that are the book and film of Poor Things have an important contribution to make to that conversation, and both, like Bella, must be ‘made’ with reference to any number of variations on differing elements of fact and fiction (any film star for instance is of necessity BOTH), nature and art and, of course, at some level truth and lies.

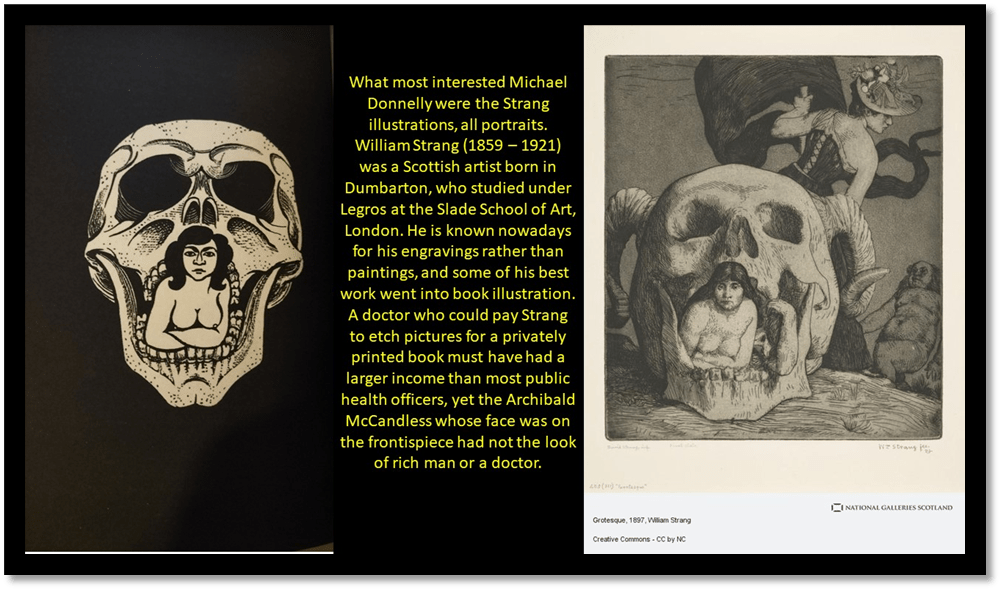

This is fascinating in both works but let us start with a small detail from Alasdair Gray’s book, from the spurious introduction which Rodge Glass, Gray’s biographer, says bluntly : ‘His introduction was a lie: …’.[1] For I think we must be less blunt than Glass is with these questions. It deals too with Gray’s visual art in Poor Things which Liliane Louvel calls its ‘iconotext which imparts the text with its own iconorhythm’.[2] Unlike Louvel, who appears not to believe the fact of William Strang’s existence, seeing him as ‘one of Alasdair Gray’s aliases’, chosen, she later hints, because of the pun available on his name, which she records as ‘William Strang(e)’. In fact, the facts, as Gray gives them, are the same as those in the National Gallery of Scotland’s record and I think we would be advised that far from just punning Gray evoked Strang in part to place himself, with serious as well as comic intent, in relation to the history of Scottish art. Let me start with a collage:

Referring to the icon on the left of the collage above, which appears as the mock frontispiece and endpiece of the fictional McCandless’s fictional account, is described by Gray as a ‘grotesque design … by Strang’, which Louvel apparently re-describes as one of ‘Strang’s allegedly original illustrations’. But Louvel is too blunt here, like Glass above. For it has to be remembered that Gray, even in alias as ‘editor’ is not saying these ARE Strang’s illustrations, for he has told us that that manuscript containing them was lost, they must therefore be Gray’s reproductions from memory or other source within the fiction elaborated here. Moreover in referring to a ‘grotesque design’, Gray can be thought to be referring not to the printed form but an original design of an icon of a skull with a woman appearing our of its mouth. And, such a design exists, the National Gallery of Scotland’s print is above on the right, and it titled ‘Grotesque’. Gray then can be considered not to have diverged from fact in his fiction in relation to Strang, although he does so much more obviously in the portrait illustrations supposedly by Strang, in which many games are played, including the labelling of a drawing of the aristocratic artist, and model of Proust’s Charlus, Montesquieu as if it were a likeness of Charcot.

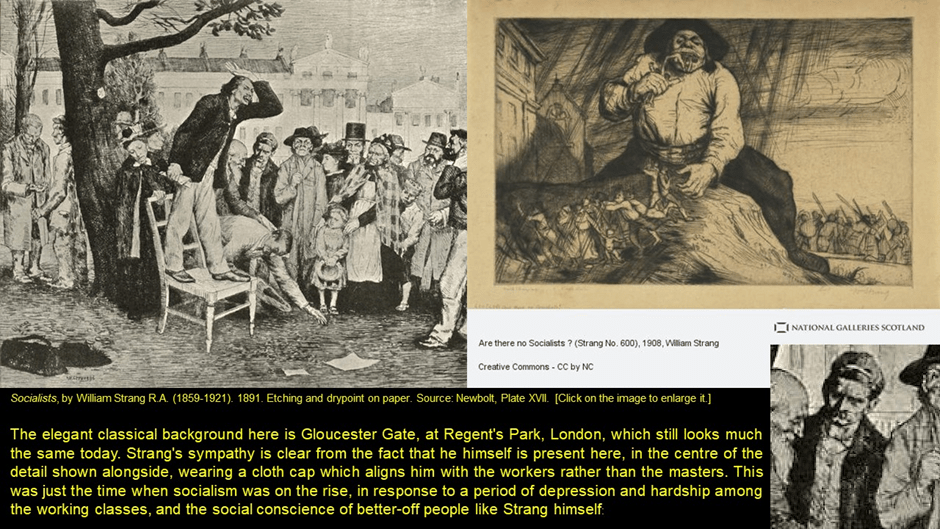

The more refined reading I want to establish here is that Gray is not merely lying but insisting that art reconfigures what is supposed to be nature, fact and truth differently, in a manner in which fiction plays a part and that this is true of life too. In blog I cited Bella’s thoughts about the word ‘ugly’, in which she says, using irony against the fact that she has taken her view of the world mainly from Punch: ‘The Socialists are ugliest, very dirty and hairy with weak chins, and seem to spend their time grumbling to other people at street corners’.[3]It is a small point, but I wonder if such a passage recalls to Gray one of Strang’s most famous prints, the 1891 Socialists, which deals with a similar scene in which Strang inserts himself as if in empathy, as the Arts and Crafts Movement he was part of generally was, with the working-men who listen to the Socialist speaker, rather than the rich, with which he was, in class terms, more properly aligned. Evoking Strang is even more appropriate for a book dealing with ‘poor things’ including poor people in the light of Strang’s 1908 print Are There No Socialists? Which shows an iconic bourgeois dining off the poor, who have had recourse to food riots. Decide for yourself:

This quibble with Louvel, whose essay is extremely intelligent overall, matters to me because I think we need to see Gray addressing the issue of lies and the unnatural in art in a highly nuanced way despite the broad humour, for what the status quo recognises as the truth, nature or fact is usually a highly ideological version of those concepts that works against the marginalised and unrepresented including women, children, animals, people labelled as ‘disabled’ or ‘insane’, wage or sex prostitutes, or queer, all of which are represented positively and with understanding of their ‘making’ as social monsters by a warped patriarchal and capitalist society. Gray does stuff by play with fiction-making, Lanthimos’ film much more implicitly by the use of styles of alienated film-making including cinematography and performance in his acting group.

One of the fictions underlaying this book, as I have said before for different reasons, is that it is a set of edited papers (edited by Alasdair Gray) originally compiled by a man named Archibald McCandless M.D., which he leaves for his wife after his death and which tells of his long courtship of his wife (as he sees it). In Blog 2 we have already seen his wife sees the point of the story as quite other – it is about his repressed love for her former beloved rescuer, Godwin Baxter mediated through her in a three-way relationship. The whole novel ends with a set of ‘Notes Critical and Historical’ that also lack true historical authority and must be distrusted, such that they too weave fiction into some indisputable facts, as occurs above with William Strang.

Amongst much that is untrustworthy in this book, the illustrations of place are true representations of places in Glasgow and London as they were at the supposed time of the story and come from trustworthy sources, though Louvel rather diminishes them as ‘a hotchpotch of images’ from sources biased to finding images that are ‘popular and cheap’.[4] The reproductions in the book had, it seems to be recreated because of the loss of the original but it appears Gray maintains their authenticity as Strang’s ‘design’, as I said above, however he meant that word ‘design’ to be interpreted. In 2010, whilst acknowledging Strang’s original print of ‘a woman leaning out over the jaw of a huge skull’, Grotesque, he goes on to say: ‘As I frontispiece of this novel I drew Morag (Gray’s wife) in the same position’.[5]

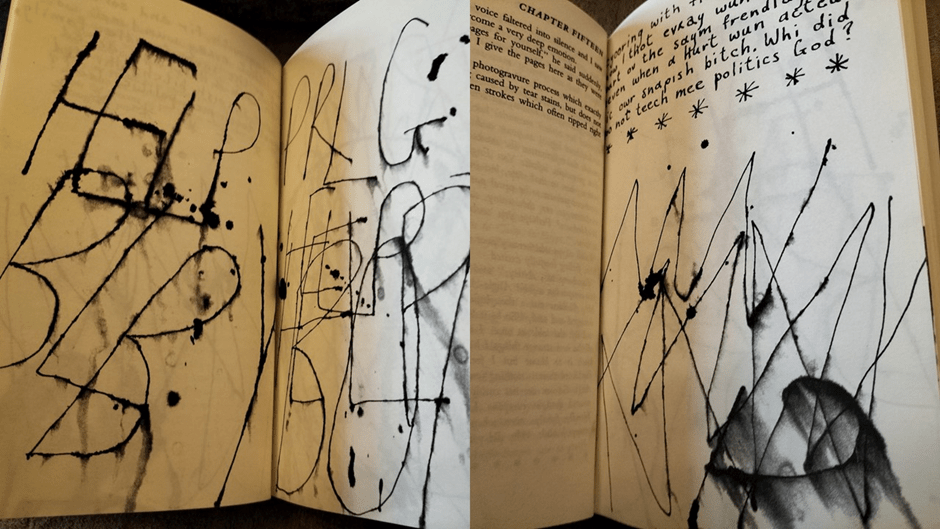

Some apparently reproduced material would of course have to be remade for they were of the supposed making of the fictional Bella, especially where she regresses from relative articulacy in language and calligraphy to the apparent disorder of the yet unformed communicator on paper. Here are examples in a collage:[6]

Such pages, strictly speaking, cannot be read and this is why Baxter does not, as usual merely read out Bella’s text to Archibald, silently correcting, or interpreting, her spelling and other errors consequent of her developmental age, but just offers them to be read by Archibald. Archibald in turn offers them for reading but in printed form, using ‘photogravure process’. This process, Archibald says, ‘reproduces the blearing caused by tear stains, but does not show the pressure of pen strokes which often ripped right through the paper’. The point is in all this that we can only ever ‘read’, and hence know, through ways mediated, filtered and the ‘edited’ by others. And in those mediations how truths might be tissued with lies, nature distorted (for are what looks like runs in the ink really ‘tear stains’) by artifice, or fiction interpenetrated the facts, if there were not actually fiction in the first place. The underlying issue is that the original situation we are reading about is endlessly layered over by representations and translations of representations in different media. In the end the issue is the same as with ‘truth, nature, and fact’: they lie under layers of that which is not them, such that they are a collage with ‘lies, artifice, and fiction’, even without considering where myth enters into the picture. Hence, the problem with the McCandless ‘original’ text and the ‘truth’ it recounts – they are endlessly recessive, and made up of fragments. In fact as Louvel says that is why the main ‘monster’ of the text of ‘Poor things’ is the text itself, wherein the joins between the fragments become apparent.

When Gray in the introduction tells us of his rift with Michael Donnely, the rift may be a fiction but Donnelly and their original friendship is not as I showed in Blog 1.The rift is based on Gray’s supposed, but actually fictional ‘trust’ in the authenticity of the McCandless document. Donnelly, Grays says, need more evidence to support the factual nature of the document, which Gray refused to search for. Donnelly is presented as distrustful of imaginative or poetic truths, as historians oft are. In contrast Gray in ‘editorial persona’ affirms his edition is a ‘tissue of facts’.[7]

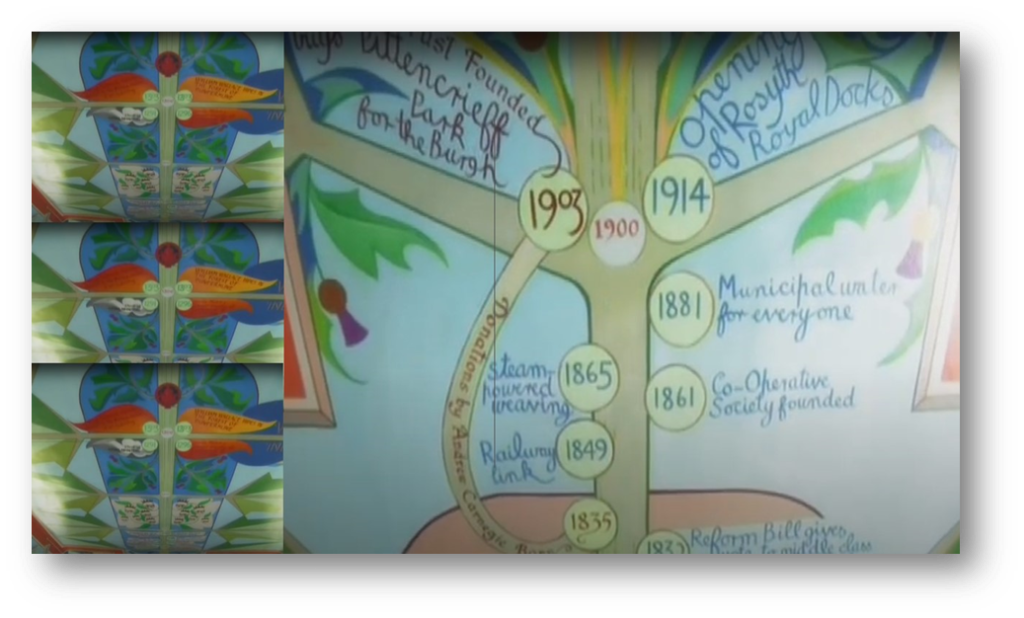

‘Tissue of facts’ is an interesting term since only lies are usually named as being the layered contents of a tissue, for the word tissue is thought by some (but without certainty) to refer to the complicated interweaving of fabrications. The existence of Michael Donnelly though, is just one of the facts that interweaves with fictions. Gray says that he has ‘written enough fiction to know history when I read it’ whilst Donnely says that he had ‘written enough history to recognize fiction’. Gray determines to therefore ‘become a historian’.[8] Of course both argue from each end of a false binary. Donnelly, in ‘fact’, had not a ‘soured’ relationship with Gray and was (with Elspeth King who had with him ran Dunfermline’s The People’s Palace Museum) been responsible for overseeing the great ceiling painting in The Long Gallery’ called The Thistle of Dunfermline’s History at the Abbot’s House Local History Museum (see the collage below for a taste of the interwoven truth), whose whole meaning was how myth, metaphor and fiction (a ‘thistle’ like that in Hugh MacDiarmid’s great poem) interpenetrate all Scottish history. Donnelly was a supporter of this view.

In a ‘tissue of facts’, then we should expect fiction and fact to commingle, but the point is I think that history is oft such a tissue, where fiction attempts to interpret or re-interpret the facts combined therein, as if independent of their necessary invention. And herein lies an issue in the way this book translates into a film, wherein most violence is done (if you want to see the contrast in that dramatic manner) to the character who creates Bella from the corpse of the suicide Victoria Blessington, Godwin Bysshe Baxter, for Baxter, in the film, is, as Wendy Ide accurately describes him in her review in The Observer, an:

unorthodox genius Dr Godwin Baxter (Willem Dafoe). Called “God” by Bella, Godwin bears grotesque scars on his face and body resulting from his childhood experience as the subject of his father’s deranged scientific curiosity – an experience that failed to stymie his own rather baroque quest for empirical facts.

And that is about it. God is made to stand for the principles of empirical science in the film (an element it takes from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and William Godwin, her father’s, early rationalism. He is shown to entirely control Bella, unlike Baxter in the novel who virtually gives, if sadly, Bella to McCandless and supports her independence by taking her to Europe before she goes there with dissolute Wedderburn. Even the latter elopement he reluctantly supports with money to offer Bella an escape route (though that latter detail IS in the film).

He, in the film stands for the principle in empirical evidence-based and experimental science completely, of the need to control variables not involved in his ‘experiment’, the ‘extraneous variables’. This is why in the film Godwin keeps her locked within his Gothic mansion of many layers and rooms. Once Bella goes to Europe, he gets another ‘subject’, Felicity, to experimentally test alongside his collaborator, Max McCandles . That is not the ‘God’ of Gray. That ‘God’s’ hope is not for the attainment only of valid and reliable experimental results from the observation of Bella’s dependent variable behaviours but the hope that she will freely choose him as her life-companion, romantically, domestically and as asexually offering cuddles without orgasm. This is a more complex ‘God’ than that in the film, and it is he who first introduces Bella to the realities of the divided society in Glasgow because, in her agony in Alexandria, she stated ‘Whi did yoo not teech mee politics God?’.[9]

In the film the issue of truth and lies is endemic in the fantastic settings, wherein fiction ties in with a muddle of anachronistic historical raw materials, in the analysis of the marginalisation of woman in roles that fail to satisfy them or use their talents, and in the insistence that behaviour is more complexly determined than by simplistic accounts posing as ‘truth, nature, and fact’ and involves beliefs (that might otherwise be known as ‘lies, art, or fiction) like the existence of Gods, or even abstract Reason, that act as determinatively as the former elements. One way the film does this is play with tropes from the history of film – Gothic film obviously but not that alone. There are also films of a girl’s development evoked (and subverted), not least Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and its sequel Through the Looking Glass, especially in the range of costumery and make-up.

Make-up is itself an act of belief in the power of appearance that does not stop at disguise. Some believe that how we dress reveals inner truth (Carlyle in Sartor Resartus for example).

Moreover, the film insists that all events can only be made into stories through some filter of narrative technique, such as the fisheye lens used commonly to represent the queerness of events, and/or the tunnel vision of the yet-to-be perceptually mature, or those who fail to see the margins of reality. Appearance itself involves false stories that have complex origins in historically established representations and ideologies. We call some of them stereotypes. The look of a ‘monster’ for instance, is usually regulated by what we have shown in the past to be a monster.

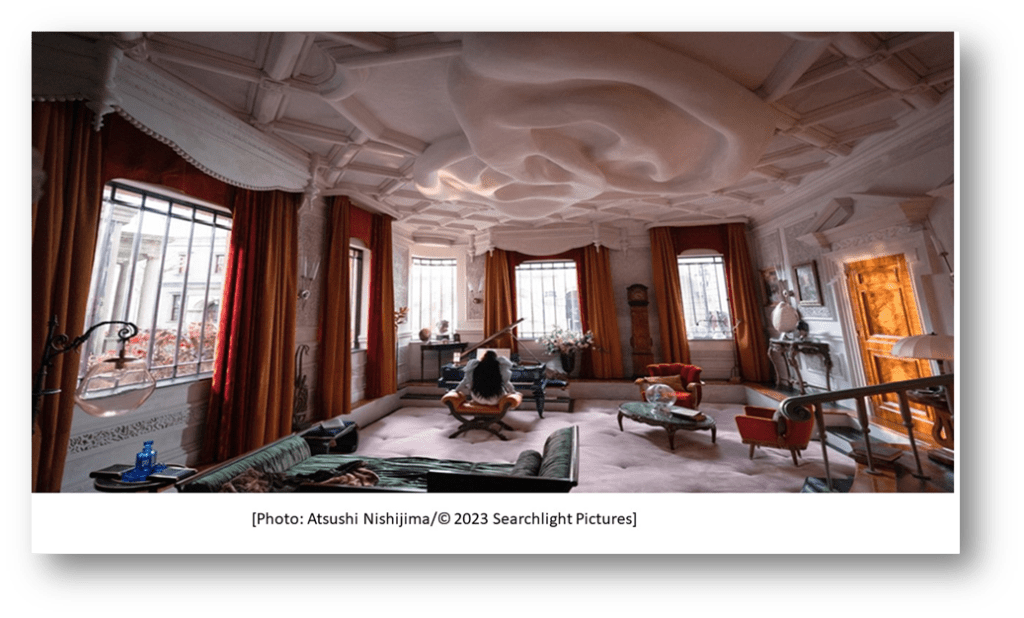

Even stills from a film contain stories that are a mix what we factually see with performative behaviours there represented but reduced to stasis that become expectations based on lies, fictions and artifice – thus the fact that McCandles sees Bella at play in a huge room is a locus of stories that will begin to tell themselves in a viewer’s mind even before the story is told in the form into which the script says it must fall. Look at the still below. I think Bella there, sitting at a piano, at the focal point of our gaze but not fully seen in detail, is subject to the viewer’s expectations of such a young woman’s likely future in short and long-term.

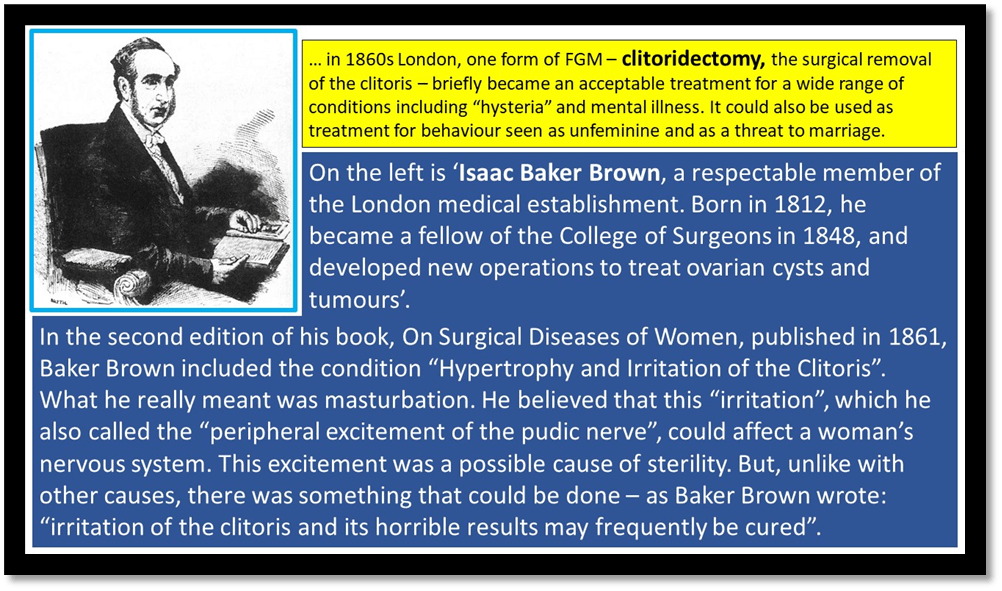

Whether fanciful or not I see the complex interweaving of those fantasies about young women in the convoluted ceiling under which she sits where strands and threads intermingle. The only way Bella can confront expectations of observer’s is to disrupt them by performance on life-skills that is awry: dropping food she hates from her mouth in public as a child would, picking up innuendo about fellatio thereafter and running with it and then because a baby annoys her, going to slap it. All very subversive! Yet in the distorted view of her in the huge piano-room, all we see is a cultured young woman submerged in a world of art who need not work, or sell anything (though as she knows marriage is the soonest route to having one’s body sold to the highest bidder, who will make you, or re-make you (surgically if necessary) fit into their story, as Blessington attempts to do by drugging her in preparation for a clitoridectomy (an act of Female Genital Mutilation – FGM) against her will, Such intrusions into women’s control over the stories they were allowed to enter was common in the nineteenth for ‘over-sexed’ women, though the judgement of being ‘over-sexed’ was not those but those of a male authority, usually a husband and collusive doctor.[10]

And the facts about the story of women in the nineteenth-century are still there to see. For the windows are barred. A life of wealth may still be a life in prison.

Text from: Helen King (2018) ‘The rise and fall of FGM in Victorian London’ in “The Conversation” (online [Published: March 12, 2015 2.14pm GMT •Updated: October 29, 2018 11.20am GMT] Available at: https://theconversation.com/the-rise-and-fall-of-fgm-in-victorian-london-38327

One shouldn’t finish however, without due praise to Emma Stone, for she is the meaning of the performative performed. Her every action is about how behaviour is moulded from a raw material wherein the learning of posture and stability also becomes the learning for a woman of much more about the pre-scripted role of women in patriarchal capitalism. It gives the only energy left to the remnants of Gray’s plot concerning Socialism to the film. It is a socialism adopted through feminism though, whereas in the novel socialism, feminism and the defence of the marginalised are a package where no strand seeks to dominate. Gray’s world though is not the one we now live in. But forget Barbie; this film will take you into a radical fantasy much more appealing and coherent than Barbie – and perhaps next move onto the novel. See the film if you hesitate with the novel, but don’t hesitate to see the film, even if you prefer the novel. For the film offers delight Gray could not himself have imagined. Though true Gray fans find the film harder to watch than others. Personally,, I wish I had re-read it AFTER seeing the film not before.

With love

Steven xxxxx

[1] Rodge Glass (2008: 222) Alasdair Gray: A Secretary’s Biography London, Bloomsbury Publishing.

[2] Liliane Louvel (2014: 187) Itching Etchings: Fooling the Eye or an Anatomy of Gray’s Optical Illusions and Intermedial apparatus’ in Camille Manfredi (Ed.) Alasdair Gray: Ink for Worlds Basingstoke & New York, Palgrave Macmillan 181 – 203.The terms iconotext and iconorhythm are Louvel’s own and appear to mean respectively, a written text with inset graphics and the patterns of recurrences between graphics and writing within such a text

[3]Alasdair Gray (1992:127) Poor Things: Episodes from the Early Life of Archibald McCandless M.D., Scottish Public Health Officer London, Bloomsbury Publishing.

[4] Liliane Louvel op.cit: 187

[5] Alasdair Gray (2010: 242) A Life In Pictures Edinburgh, Canongate Books

[6] Alasdair Gray 1992 op.cit: 146f. & 144f. respectively in collage

[7] Ibid: XIV

[8] Ibid: XIII

[9] Ibid: 145, translated ibid: 143 ‘Why did you not teach me politics, God?’.

[10] Helen King (2018) ‘The rise and fall of FGM in Victorian London’ in The Conversation (online [Published: March 12, 2015 2.14pm GMT •Updated: October 29, 2018 11.20am GMT] Available at: https://theconversation.com/the-rise-and-fall-of-fgm-in-victorian-london-38327

Great review! I’m definitely looking to see this one soon. I was such a fan of Emma Stone whom I consider to be a terrific actress. She had seldom ever disappointed me in movies. Loved her Oscar-winning turn in “La La Land”. Here’s why:

LikeLike

Insightful analysis of the book. I haven’t read it but am definitely looking forward to seeing the film adaptation soon. I’m a big fan of Emma Stone who has proven an extraordinary actress. To cite an example, I adored her Oscar-winning performance in “La La Land”. Here’s why I loved that movie:

https://huilahimovie.reviews/2017/01/01/la-la-land-2016-movie-review/

LikeLike

Great book review once again. I recently had a chance to see this film finally and absolutely loved it. A brilliant adaptation of the beloved book. Emma Stone was extraordinary. Here’s why I loved it:

LikeLike