Have your even seen ‘old Durham Town’? Not till Ben Myers showed it to me again! The role of art in turning places into spaces in which the imagined can dwell.

Geoff and I are just on our way to see Poor Things, an exceedingly well-received film in the newspapers based on one of my favourite novels of Alasdair Gray. To prepare myself to confront what they have made of my hero, I started re-reading the novel and it is as fine and as innovative a thing to me now as it was when I read it first, soon after it came out. I remembered my delight especially with the scenes in Glasgow around the River Kelvin, a venue I love though imagined at the ugly height of the Industrial Revolution, to which Gray took the filmmaker when the film was mooted well before Gray’s death.

Just before I came out for the cinema visit, at the Odeon at Durham a BBC article on line became available, from which I append below the captioned photograph and an extract, enough to show that, the film entirely ignores Glasgow meetings for film sets and mid-European venues.

A decade later, with a screenplay by Tony McNamara, the film began shooting on a set in Hungary, the Glasgow locations replaced with futuristic versions of Paris, Lisbon and London.

It has led to a frenzied debate on social media about whether the loss of the location has lessened the film.

Pauline McLean (2023), BBC Scotland arts correspondent, available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-glasgow-west-67957694

My immediate reaction is shock, for it seems to me that Glasgow is essential as a place in socioeconomic and political theory for this novel, with The People’s Palace setting too implicated in that theme too, to the novel’s metamorphosis from its origin in the Frankenstein story, an origin definitively mid- European in most of its settings, and to which this film seems to return his story. Gray draws attention to the difference in the classes and locales of his version. Bella is, of course, to some extent Mary Shelley, her maker (for she is the ‘monster’), is based on Mary’s father, William Godwin, and named Godwin Bysshe Baxter in the novel, Bysshe for Mary’s husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley, of course.

How will I forgive the film. Read my blog tomorrow to see. But as I re-read the novel I think about how Gray grasped Scottish landscapes and cityscapes in his novels, from Lanark onwards, and I wonder if it matters that the film is cavalier about ‘place’. I have a few times in blogs speculated on the difference between places whose names and ‘sights’ we know and the imaginative and imaginary spaces that artists turn them into, as Van Gogh with Arles, Dickens with London or Stevenson with Edinburgh.’ You can connect with these speculations through this link if you wish but they aren’t necessary.

In Gray, Glasgow is a landscaped and civic reality. It merges with the political discourse of the novel as well as the landscapes do, all elements of Gray’s world throughout his life and art. Glasgow is the focus of an imagination rare in that regard, that dissects and revivifies a city torn between discourses’ like those of Adam Smith and Malthus, both important in the novel, and a focal point of socialist politics both in its people and intellectuals. No-one could have written it like Gray so that Glasgow becomes a space for the aesthetic but also socio-economic and political imaginations of its potential for recreation. So it matters to me that Glasgow has been cut out. But now I am at the cinema and I will see and report back.

But the real reason I wanted to use these previewing thoughts has nothing to do with the film but a lot to do with how we see local places when we visit them. Durham is the city of the County I live in. I visit each Sunday and often on other days. I attend events at the cinema, the Gala Theatre and Durham Cathedral. My husband and I walk our dog Daisy around the loop of the river. But though I visit it often, do I see it. Does it come alive to me imaginatively as Glasgow does to Alasdair Gray. I have to admit that it has only done so recently.

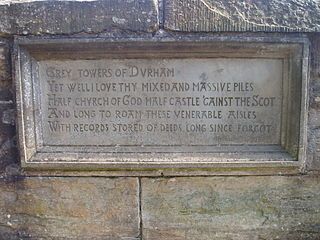

Durham needs to be a space that imaginative literature transforms - and it needs to be art that is somewhat more imaginative than a detective series on TV or the detective genre that seems to have emerged locally recently in decent popular novels by local novelists, for these exist. It also needs to be less backward-looking than the great Turner paintings (backward looking even in the nineteenth century). I was aware of course of Sir Walter Scott’s literary encomium that is engraved on Prebends Bridge, but neither those lines (see below) nor the whole repertoire of his poetry really rises to the level of art, although his Waverley novels definitively do.

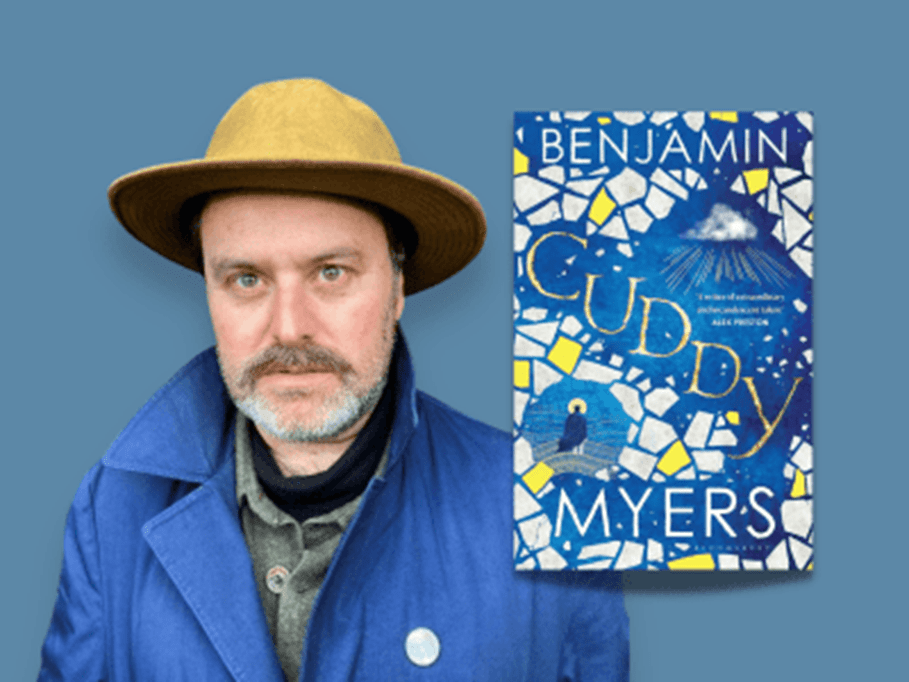

It took Ben Myer’s novel Cuddy (2023) – see my blog at this link – to do this to Durham for me for the first time and unite within it a space for imaginative narrative, poetry and vision. I won’t repeat what I say in the blog but I will insist it is not only to do with the history and integrated mythologies of St. Cuthbert ( the Cuddy of the title) or indeed just with the Cathedral, but also with the way in which Myers makes its people live and metamorphose in history and the lies and fiction that sometimes displace history for political purposes.

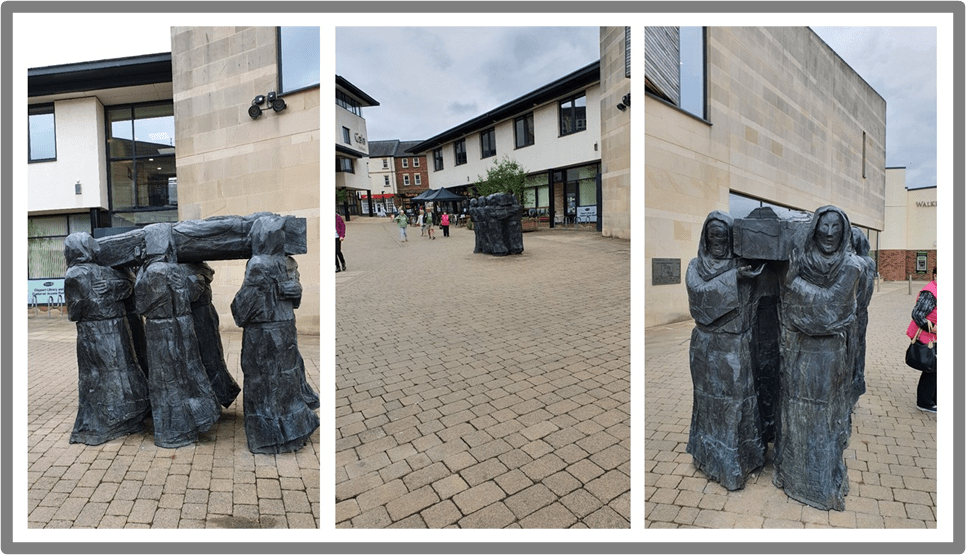

Take the group statue dedicated to St. Cuthbert’s monks, those carrying his corpse to a resting place that started off unknown until ‘revealed’ as the home required. It was then though just a small hill in the embrace of the Wear. Myers makes his modern-day characters see that group-statue, in the square outside the Gala Theatre. And, in a novel where this group of carved figures live, imagined as they might have been in Cuthbert’s company, or reimagined and seen as ghosts by various people through the intervening history of the place, makes it live, in every sense of that word, for me, in a much broader space; where myth, imagination and perception merge, in a way I had not thought possible before of my adopted home city.

Maybe we become habituated to some spaces so they can be nothing more than places, labelled by a name, Durham, and by stock narratives of their everyday meaning to you. Geoff and I often go to the Gala Theatre but on the night we went to a dramatised reading of parts of Cuddy by actors, including Toby Jones, it made seeing those statues of the group of monks in the square afterwards seemed a different experience. This was not just because of the wonderful reading, for it came entirely from the early medieval story told in the novel, often in inspired verse: it was also because I remembered the modern day characters in the novel also visiting the group statue and breaking through during that visit the normal tourist narratives that explain its presence. One of the characters tells the other the stock stories behind the piece, as students oft do, only for him to understand them differently – being not a student – and with an addition of personalised fictions.

Now Myers does often transform places he knows, such as those in the Calder Valley in which he now lives, in The Gallows Pole, for instance.But Durham was his birthplace and in this novel, he does with exactly the skill that Gray does with Lanarkshire and Glasgow (and as Scott does too for The Heart of Midlothian).

Hence, when I came out of the cinema, though my head was buzzing with these and other questions about how the film Poor Things transforms for good or ill, or into just a different experience, the novel of the same name, I lingered outside the cinema. Some views of Durham in the evening are inescapably, if possibly sentimentally, romantic. Yet Myers changes them. The central mound housing wild garlic plants becomes a place monks had either or both sex and romance amongst them. That makes them real.

Such pieces of the city might seem easy pickings for writers (they appear in the detective novels) but what of the view I took when I turned my back on that latter view, and took a view that just might be any modern city, in which a river runs through it (to cite the blog at this link).

But Myers novel lives in that homogenised city too and, in transforming it in story, he also merges issues of how such cityscapes arose from socio-economic and political history and their mythologies, including the devastating destruction of values that was Blatcherism, but mainly Thatcherism.

So that’s my reflection for tonight. There are places in the little county of County Durham I may never have visited but I wanted to answer this question by showing that visiting may be so superficial – you might see no more than a well-illustrated guidebook might tell you of them without visiting. For a place to become an imaginative space, every city needs sons like Ben Myers (though of course daughters or non-binary people would do the job too).

All my love

Steven xxxxx

4 thoughts on “Have your even seen ‘old Durham Town’: Not till Ben Myers showed it to me again! The role of art in turning places into spaces in which the imagined can dwell.”