Once we normalise play and rid ourselves of ‘Bunbury’, then at last play loses its integrity in order to be just playing Earnest (not fun): Queer play in Christopher Marlowe, Michelangelo & Oscar Wilde

I am intrigued by this question and have always been interested as a student of literature, history. art and psychology in the function of play. But there’s the rub, I suppose. Once, you admit that play has a ‘function’, you begin to abstract it from itself as a thing that must justify its role in the political, social and economic world> it can no longer be long defended in simple terms, and proven just by the pleasure it offers. Hence, for my take on this question I will reflect on the nature of play and pleasure in artworks. This allows me to effectively resist defining my own self-defined moments of ‘play’ or ‘playtime’, except as a reader or observer / participant in art. I have to face the fact that I do not find the term ‘play’ to be one that could ever describe me or my actions these days, except in highly qualified and conditional ways, to describe for instance various experimental articulations or actions that I do not wish to commit to, or appear, at least, to commit to (such as when we say to excuse a faux pas to others that I only said it ‘in play’ after all).

Only entitled cultures play for their own sake and these are cultures that are the least democratic and conscious of no social obligation, other than one they feign, for play is not, whatever anyone says, cost-free. These entitled cultures are those ridiculed by Attic Drama in fifth and fourth century BCE, aristocratic cultures that need have no regard for matters of state beyond a reflection of their desire: in Athens they were sometimes cultures supposed to be those of a less earnest Thebes than of Athens, whether they appear in tragedy or comedy: the Sphinx, after all, in Oedipus is a colossal game-player with her child-like riddles, as are Dionysus, the Furies and Medea, both requiring to be tamed before they become Athenians proper. In Aristophanes‘ play The Frogs (Βάτραχοι) Dionysus, usually a lord-god of misrule, must become earnest about art and its socio-politics (he opens in it as a buffoon and joker), especially that of tragedy, by seeing it at its best when its purpose is clear – the redemption of Athens. For even Athens feared the wantonness of aristocrats who were still playing at life, such as Alcibiades (whom some see as the true target of this play) in his self-serving military adventures – the argument is summarised in the Wikipedia entry). And Aristophanes knew the need for a mercantile trading class.

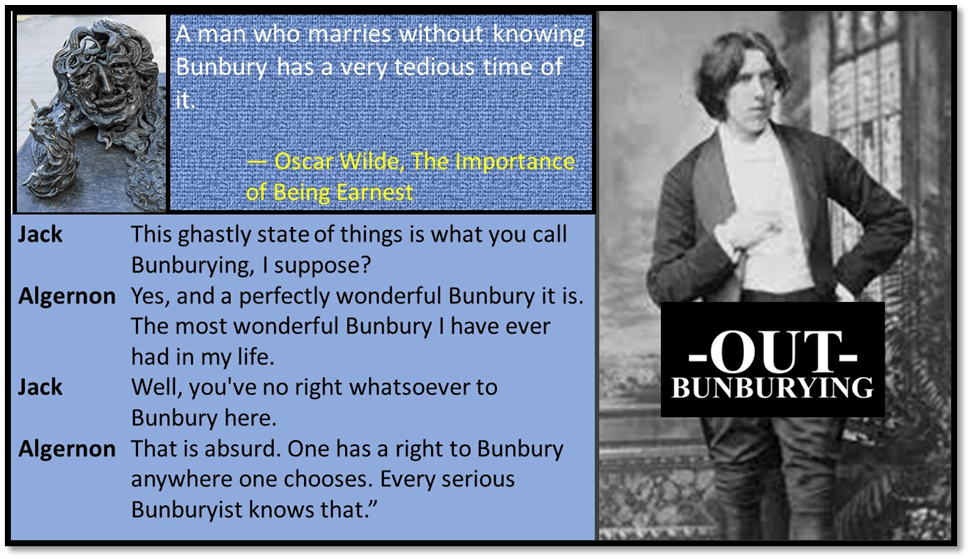

This is true of Renaissance Italy and England (the latter a little later in time) too. These were not bourgeois cultures but the influence of ‘trade’ ensured that such issues were prominent when assessing play in plays, not least in The Merchant of Venice. In bourgeois dominated cultures, leisure and pleasure for their own sakes (except as a means of refreshing the work ethic later) have a poor press overall and do not have any ‘right whatsoever’ in a world where everything, include sexual play is suborned to conventions that serve serious aims in both patriarchal and capitalist order. That’s why Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest, though a silly play – but do I say that because I think play for its own sake must be ‘silly’ – is an important one. That is indeed the game played in its title. In a society characterised by objective must pass as ‘earnest’ ones and, hence, relegate play to realms where it is more acceptable, which increasingly came to be the realm of childhood alone, and then not for long as ‘play’ becomes colonised as an educative tool and conceived as such by psychological research and theory (we are in the world now of Piaget and Vygotsky, very earnest observers and thinkers about the function of child’s play, to say nothing of Mead and less of Dewey and Froebel.

It is to the image and imagery of aristocratic cultures we need to look to in transitional cultures (most really in modern history), for in these resources are made to appear limitless, though some plays and poems turn this apparent richness into a thing worthy of critique. Yet the Renaissance loved to find imagery in which play or its ideological image is unsullied by serious considerations and the norms that serve them. Perhaps the major issue in the representation of play is that it is in the Renaissance subjected to a conscious evaluation, often presented as urgent, before any ‘playtime‘, taken away from the opportunities that capitalist and patriarchal societies think that time MUST serve. Admit obligation to others for instance, as you play, and to all purposes you play no more; you bend play to its functions.

This yoking of play to aristocracy continues in reflections in art even when the horse that served it has bolted, afraid of the heavy cart we are asking it to pull. Hence, I think the way a genre like Gothic in art reinvents play, with its joy in disguise and time out of the norms, which Gothic indulges whilst oft tying it to moral, social or political considerations, so that the ‘play’ and ‘time out’ it involves is potentially justifiable, even despite its protestations, in Wilde, at least of trying to escape these, such as continually flit through The Picture of Dorian Gray. I have had reason to think about that blend of play with privileged and entitled life-styles recently in blogging on the recent film Saltburn by Melanie Fennell for this film has relevance to much I explore in this blog too (see my Saltburn blog at this link if you wish).

Oscar Wilde in the later nineteenth century explored play most not in his prose novels or even poetry, to which he dedicated his earnest, if pagan, soul, but in comic plays – where every meaning of what play means is active. And most celebrated, as I have suggested above, is that play, of which the title is too little studied in its own right: The Importance of Being Earnest, The whole story hinges on a man named Jack, who needs, if he is to marry well, to be called Earnest. But ‘being Earnest’ is not just about a name but also about the need for moral and pragmatic serious attention to an agenda that, in all real terms, must exclude play for its own sake, just as it does art for its own sake. Else why write a playful ‘play’ about the lengths it takes to play away from home – whether one is single or married – and invent for it a wonderful euphemism: ‘Bunburying’. Bunbury is an invented friend of the key comedic character, an aristocrat rather out of pocket somewhat called Algernon. Bunbury’s frequent sicknesses and need of care give Algernon an excuse to go and play in private in an unspecified ‘elsewhere’ called ‘in the country’. Jack disapproves of Bunbury and his function but he too lives a life that is a playful fiction that years to seriousness, earnestness. The yearning may have much to do with the wealth of the dowager Lady Bracknell, for it can hardly be attributable to the rather artless Gwendolen, whose rebellion against her mother is less than skin-deep, extending to the name ‘Earnest’ but not to an earnest grasp of her responsibilities or even her desires. We know Jack will need his own Bunburys when he marries, just as Wilde did, don’t we.

Play is rarely a function of modern literatures or art except where it indicates some ethical failure or want of earnestness in the player. The best examples of this that I want to look at are in Renaissance art (and I choose to examine later works by Christopher Marlowe and Michelangelo) to do so, almost in obeisance to Oscar Wilde’s main aesthetic influences in Walter Pater and his discovery in queer relationships a source for an anti-utilitarian theory of beauty, in his Roman novel Marius the Epicurean for instance, though there is no doubt that aesthetic play in Pater is a labour Wilde must have mixed feelings about. In earlier literatures everything that is playful is that which celebrates that part of aristocratic culture remaining, the freedom to act without constraints that is blameless in children but not so in adults, with the prohibition becoming the greater as they age.This too is characterised most in the queer play we found in Renaissance art, particularly that which refuses to yoke pleasure to serious intent, whether in relationships or the social and economic world. No one is better at this that Christopher Marlowe in English verbal art and in drama.Enjoy a treat and read, if you will this tremendous piece of verse from Marlowe’s (1598?) narrative poem, Hero and Leander. Leander is a young man who loves Hero but is restrained from her. He may only win her if he swims the Hellespont to her tower. To do so, he must immerse himself in Neptune (the God of the Sea), as well as the sea itself. Neptune (‘the god’ in the opening of this excerpt) is in the mind to play, having as the aristocracy of the Gods do, time to spare and lots of ‘gawdie toies’ in his possession with which to induce a boy to play (for play and sex are concomitant in this verse and thus the strategic uses of the ver play):

The god put Helles bracelet on his arme,

Christopher Marlowe () ‘Hero and Leander’ [Second SestyiadAvailable at: https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.03.0012%3Apart%3D1%3Asubpart%3Dsestyad+2

And swore the sea should never doe him harme.

He clapt his plumpe cheekes, with his tresses playd,

And smiling wantonly, his love bewrayd.

He watcht his armes, and as they opend wide,

At every stroke, betwixt them would he slide,

And steale a kisse, and then run out and daunce,

And as he turnd, cast many a lustfull glaunce,

And throw him gawdie toies to please his eie,

And dive into the water, and there prie

Upon his brest, his thighs, and everie lim,

And up againe, and close beside him swim,

And talke of love: Leander made replie,

You are deceav’d, I am no woman I.

Thereat smilde Neptune, and then told a tale,

How that a sheapheard sitting in a vale,

Playd with a boy so faire and so kind,

As for his love, both earth and heaven pyn’d;

That of the cooling river durst not drinke,

Least water-nymphs should pull him from the brinke.

And when hee sported in the fragrant lawnes,

Gote-footed Satyrs, and up-staring Fawnes,

Would steale him thence. …

NEPTUNE AND LEANDER, André Durand, Italy, 1999, Oil on Linen, 183x183cm Available at: https://www.singulart.com/en/artworks/andr%C3%A9-durand-neptune-and-leander-867451

There is a lot of play here and is intensely homoerotic as well as sportive and illusive, playing with disguises that mislead or ‘deceive’. Not that Neptune would use the term ‘deceive – this is about taking on roles to enhance the imaginative pleasure that is otherwise mundane even in real flesh and in purposive sex, such as the kind Leander thinks this old guy, temporarily ‘deceav’d’ by Leander’s lovely limbs, to think him a ‘woman’). But sex/gender is not even relevant here in this or indeed any other play that does not serve an ulterior purpose or function, like that Leander labours towards in swimming the Hellespont, like Helle herself. Sex with Hero such as it is in this poem leads to fatigue, exhaustion and death, very serious things.

Marlowe touches on this again in dealing with Edward II’s defiant (defiant of wife and the nobles of the realm who are into serious business) love for a male commoner, Piers Gaveston, and in the opening of Edward II, Gaveston is the very manifestation of every kind of play you might imagine. He turns away the pleas of serving soldiers hurt in the King’s wasteful wars saying they cannot serve him, for they are not ‘men for me’, instead, his men must be more expert in play than earnest service:

I must have wanton Poets, pleasant wits,

Christopher Marlowe ‘Edward the Second’ Act 1, Scene 1. Available at: https://emed.folger.edu/sites/default/files/folger_encodings/pdf/EMED-Ed2-reg-3.pdf

Musicians, that with touching of a string

May draw the pliant king which way I please:

Music and poetry is his delight,

Therefore I’ll have Italian masks by night,

Sweet speeches, comedies, and pleasing shows,

And in the day when he shall walk abroad,

Like Sylvan Nymphs my pages shall be clad,

My men like Satyrs grazing on the lawns,

Shall with their Goat feet dance an antic hay,

Sometime a lovely boy in Dian’s shape,

With hair that gilds the water as it glides,

Crownets of pearl about his naked arms,

And in his sportful hands an Olive tree,

To hide those parts which men delight to see,

Shall bathe him in a spring, and there hard by,

One like Actaeon peeping through the grove,

Shall by the angry goddess be transformed,

And running in the likeness of an Hart,

By yelping hounds pulled down, and seem to die,

Such things as these best please his majesty.

National Theatre, Edward & Gaveston, available at: https://theartsdesk.com/theatre/edward-ii-national-theatre

It is common to say such verse is sexualised but surely that misses the point for sex and play are indistinguishable. Gaveston is a moral leper nevertheless – his play is purposive: it seeks ‘to draw the pliant king’ for Gaveston’s own advantage, and neither the Queen nor Parliament of nobles are wrong about this, as Gaveston’s honesty in soliloquies to the audience alone show. Otherwise he seeks to use play to deceive, quite unlike Leander who does not want to play at all. Nevertheless Marlow clearly relishes playing with the forbidden (more disturbingly in The Jew of Malta), Moreover, the liminal breaks through the norms that sustains binaries as theatre, sculpture, painting, architecture, verse and music all seem designed to do (making illusions seem real). The Diana hidden here is a ‘a lovely boy’ (as of course he would be in the Elizabethan theatre). Pain, pursuit and death (the consequences of amorality) are here not sexualised as much as aestheticized, pleasure in the sight of the fair and naked, that usually hidden like ‘those parts which men delight to see’, offered for appreciation of the haptic feel of the illusion, neither purposive nor realisable other than in a mix of emotional and cognitive stimulation. Androgyny is central, reproduction of ideology or beings not even a thought or a feeling.

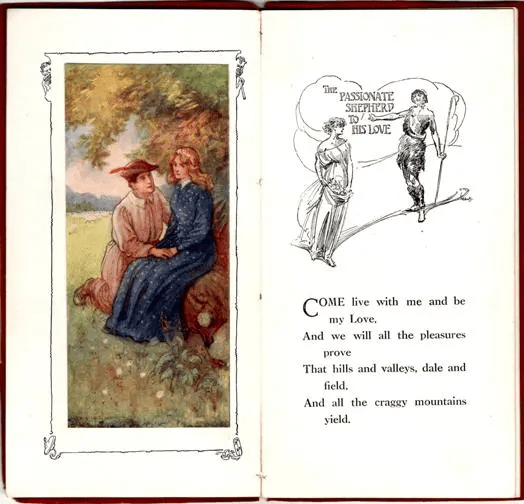

Marlowe is often critiqued by his peers for such moments. Take his wonderful lyric A Passionate Shepherd to his Love, a riff on much Latin poetry, which as satirised (if that is word – I prefer saying something like metamorphosed from the playful to the earnest) by, the political realist pirate courtier of Elizabeth I (she called him ‘Water’, hence his poem The Ocean’s Love to Cynthia – Cynthia was one of the many mythological names of the playful Queen between serious politics) and and great poet,Sir Walter Raleigh, and John Donne. Thus, the playful Marlowe, or a taste thereof (the full poem is here at this link).

Come live with me and be my love,

And we will all the pleasures prove

That valleys, groves, hills, and fields,

Woods, or steepy mountain yields.…

The shepherds’ swains shall dance and sing

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44675/the-passionate-shepherd-to-his-love

For thy delight each May morning:

If these delights thy mind may move,

Then live with me and be my love.

Raleigh determines that such play is not worth the biscuit. Play that is all shows and promises and pretends that it is a May morning all day (and night) and throughout the year to stone-cold Winter) is bound to leave the player disappointed and perhaps bereft of support and life. In his poem published only a year after Marlowe’s at least, The Nymph’s Reply To The Shepherd (1600) he imagines himself as the loved one, a nymph though since sex/gender are part of the issue, addressed by Marlowe:

If all the world and love were young,

And truth in every shepherd’s tongue,

These pretty pleasures might me move

To live with thee and be thy love.…

But could youth last and love still breed,

Had joys no date nor age no need,

Then these delights my mind might move

To live with thee and be thy love.

The issue is that time matters in a world of inequalities where a poet’s fiction or a shepherd’s lie might lead to ‘cares to come’ about which nymph or man needs to be aware. Love is a game with consequences in this man’s mind, where one player might start a game only for the other to find themselves the victim thereof: he the fisher, the loved one the fish and playful promises ‘The Bait’.

Come live with mee, and bee my love,

And wee will some new pleasures prove

Of golden sands, and christall brookes,

With silken lines, and silver hookes.

There will the river whispering runne

Warm’d by thy eyes, more than the Sunne.

And there the’inamor’d fish will stay,

Begging themselves they may betray.

…

Let coarse bold hands, from slimy nest

The bedded fish in banks out-wrest,

Or curious traitors, sleavesilke flies

Bewitch poore fishes wandring eyes.

For thee, thou needst no such deceit,

For thou thy selfe art thine owne bait;

That fish, that is not catch’d thereby,

Alas, is wiser farre than I.

Of course, in one way (in its ‘wit’, use of ‘conceit’ and cleverness) Donne’s is the greatest of these poems, for only he admits that in some play, the one betrayed by promises is the most likely traitor that lead to their own betrayal. When the game of love promises such comely play as a poet’s self is (for he is art itself ) is ‘artifice’ enough to hook any fish (Donne is not specific as to sex/gender in his play except if that old trope that sees women as fish – it is in Shakespeare after all – is at play). The point is that for the ‘inamor’d fish’ the aim is not to escape your man -poet but to be that traitor who gives away your poor strategy by focusing on the delights the man-poet offers. The sexual coarseness of that conceit of the bedded fish, fingered out of its ‘nest’ by its own tendency to wander is what displaces coarser bodily interaction with more refined play.

There is in the pre-clerical Donne, I think, much that pretends he and his masters will live on forever as if he were a courtier of the Castiglione type to some potent bait, frightening in being the very aura of princely power. In that sense it plays the game of risk in hope of being kept by the current Establishment (he much favoured Laud’s new liturgy because it changed in order to keep things the same even as a cleric) rather than abandoned – it is how he is with God as with Kings and Church. In another, it is retrograde for the time it magics up and lives therein is illusory. The river and the sun continually move on but the fish feels it can hold on to time, stay, without fear of being wearied of by his captor. I would say Raleigh represented the way forward not he. He may not be offering all the pleasures’ in his near citation of Marlowe in the poem, but he will be offering some ‘new pleasures’ to prove. I am not sure that this wasn’t always the case with aristocratic culture – the rich can always afford something ‘new’ because they can afford to move on, leaving the fish (all unwise as we know) behind them, now gutted.

Nevertheless, I hope this range will show how the Renaissance so valued play (The Faerie Queene alone shows this – but A Midsummer Night’s Dream is stronger of course) that even when it critiques playful attitude with some earnest considerations, it still does so in the spirit of play. In comparison Wilde is a morbid gamester. This may have something to do with increasingly negative views of behaviours, thoughts, feeling and sensations that transgressed norma and felt queer in a negative manner – as if potentially from the world of the Undead (like Dorian’s picture) rather than one of potential illusory delight, lovely while it lasts if you let it be.

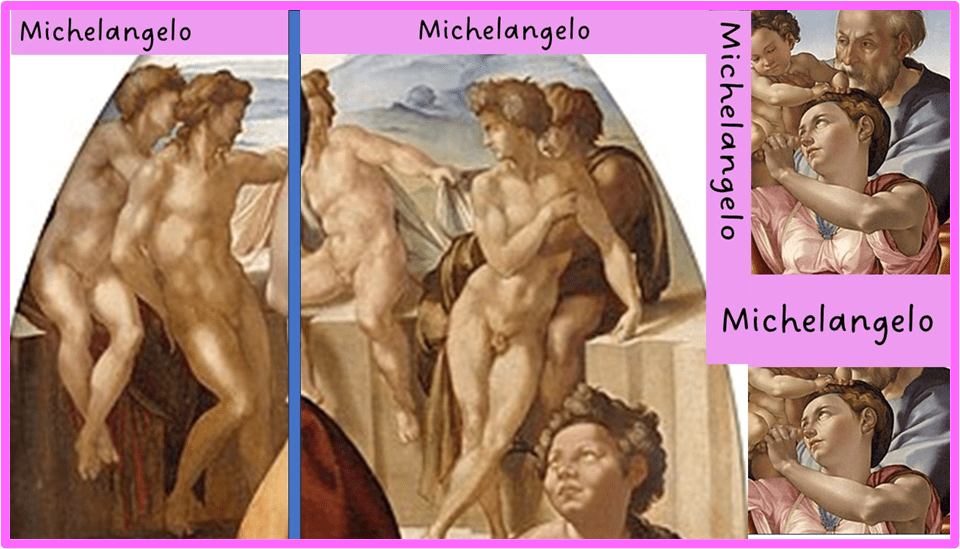

But I have looked at all this to concentrate on one picture by Michelangelo. It came to my attention again in a wonderful essay on Michelangelo I read by Eugene D. Glynn, the psychiatrist turned social-worker and husband, in effect, of Maurice Sendak. I owe to my dear friend, Charlene, knowledge of this book and I think I have more to say in later blogs of its wisdom and the relation of that wisdom to play in Maurice Sendak’s children’s’ books (I wrote about Sendak in an earlier blog at this link). Glynn writes in his brief Michelangelo essay (a review) about the Doni Tondo (a ‘Holy Family’) in the Uffizi Gallery. In his description he shows the layers the painting uses -a foregrounded Holy Family, John the Baptist slinking away to the right behind them, and yet further back’in the background, ‘five youths, very beautiful, very nude, very androgynous, again, engaged in mysterious action that seems to include homoerotic play’.

What puzzles and amazes me in this review is the word ‘again’ here for it refers back to the fact that he had also seen some dark passages, representations that lack immediate clarity of interpretation in the representation of foregrounded family whose ‘action is unclear’, in his words.(1) Note, of course, that the connection of play to both luxury of time and resources and the queer cannot be untangled here because Glynn refers to the ‘play’ ion the youths I am focusing on in the painting in ways that limit it as an example of play, First, it is ‘homoerotic play’ – a subset then of some other possible intention in some people’s minds – foreplay leading to a definite end, Second, play is merely part potentially of what those youths in the background of a serious painting with various ritual references within it, might be doing. Hence the interpretive range Glynn refers to, using conventional iconographies perhaps. Are these youths ‘examples of technical virtuosity’, as Vasari says, ‘homosexual sinners awaiting purification’, as Mirella Levi d’Ancona says, ‘angels engaged in homoerotic play’, such as Milton’s Raphael says angels do knowing no sex/gender, suggested by Leo Sternberg, or various other possibility (‘sons of Noah, athletes of virtue, mankind before grace’.(2)

In fact I think myself that the lack of easy explanation Glynn finds in these characters is not unlike that the close bodily attentions of mother, and child in the Holy Family group. Mary’s left arm and hand seems to play with the flesh on the still chubby baby at his shoulder just as her right arm and hand seem poised not just to physically support (for Jesus is precariously placed) the child, as does the one to the shoulder too) but also to tickle his lower body. Though Joseph is impassive and solid, the bodies of all three lean into each other. Mary is locked into the framework of the strong legs of Joseph, almost pressed against his lower body between his parted legs. His naked foot touches hers as hers snakes into the trinity of persons. The whole unity of the Family is fleshly (though the flesh be of mother and child), and seems (to me at least) to explain the sense of being an outsider seen in the face of the retreating John the Baptist’s face, a person for whom only the pain of divine grace is awaited and not its love. Let’s look at the youths again with those details foregrounded in our minds.

There is interplay between the bodies here, even the ones who seem to beckon and lean towards each other from each end of the wall on which they sit behind the Holy Family. I think our notion that the play is necessarily erotic though is conditional on their nudity . Only the black male figure has substantial clothing but his neighbour on the left seems to be pulling at this cloaking to remove it. There is an attempt at mergence clearly that we may think of as erotic but it is also clearly indicated as not sexually arousing, or appearing to tend in that direction. Rather, as with the Holy Family, bodies press on each other, filling the spaces bodies leave between them but not penetratively. Their phalluses are of modest size and not erect, their poses casual and containing closed as well as open gestures and postures – closed fists and crossed ankles.

Even despite myself, I think it is a mistake to see this play as homoerotic in the intention of its characters, though we forgive those male queer observers who find it invites erotic response from them. But if it is not homoerotic, it is definitively queer because it rejects every norm, even that of the homosocial in its joy in male bodily bonding – something I have in past but early blogs called homosomatism (use the link to read the earlier blog), a joy in the male body in its difference and likeness to one’s own, though I would be more convinced if some of these bodies were not so ideal in their modelling of the Ancient nudes of Greece. The bond is like that of family play, and that it is why it co-illustrates the play of flesh that dominates this picture, visually, haptically and in conception. Why it matters is that it the youths are not a family, holy or otherwise, except that they are a chosen family of males comfortable in fitting in with each other.

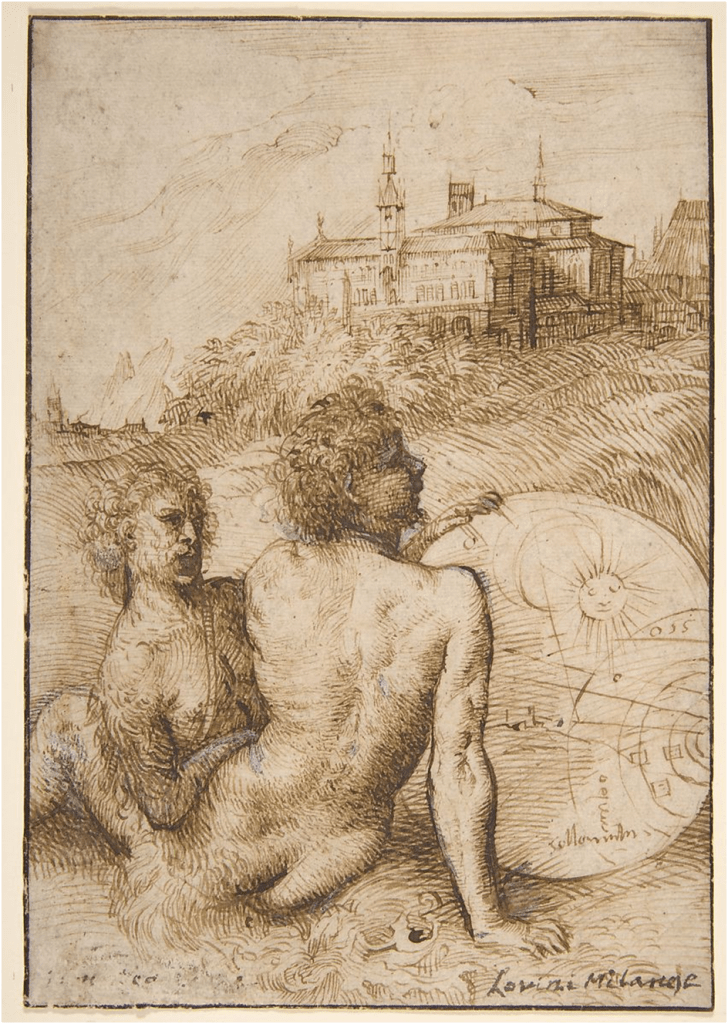

Titian ‘Two Satyrs in a Landscape’ Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/337067

I am as near to a statement here of my settled thought on this matter as I might get. Would deeply value feedback, especially that leading to discussion. Despite appearances, I can be got to change my mind. Lol.

All my love

Steve

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Eugene D. Glynn (2008: 183) ‘Michelangelo’ in Jonathan Weinberg (ed.) Desperate Necessity: Writings on Art and Psychoanalysis Pittsburgh, Periscope Publishing Ltd.175 – 187.

[2] ibid: 183

One thought on “Once we normalise play we ‘Bunbury’ it and it is at last play in Earnest (not fun): Queer play in Christopher Marlowe, Michelangelo & Oscar Wilde”