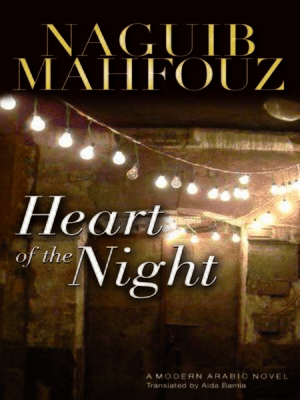

Do I really ‘want’ to read more books by Naguib Mahfouz? The psycho-cultural limitations in creating and destroying the desire to read & the ‘vital necessity’ of reading. Prompted by his 1975 novella Heart of the Night (trans Aida A. Bamia, 2011, The American University in Cairo Press).

Naguib Mahfouz (2016). “Sugar Street: The Cairo Trilogy”, p.89, Anchor

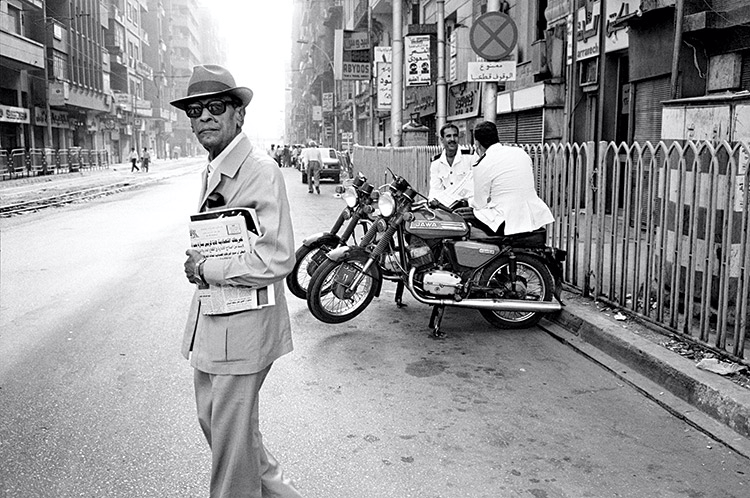

I think there may be a fundamental contradiction in the idea of only reading what you want to read as there is only believing what you want to believe. I have not read the book from which the quotation is taken as a meme for contemplation in the illustration above but it seems to be self-evident, whatever its context in that book and, for once to be perfectly illustrated by the photograph backing it. There is a road to travel on. It is evening but we stop where we want to stop and take out a book. This book may appeals to our desire. It comforts us with its pursuit of some redemptive meaning for our life-journey. It reflects those beliefs about life (that it is hard but worthwhile and compensates for what it takes away) that we have always convinced ourselves to be the case.

We bury ourselves in that book and hence barely notice that our stopping place is a desiccated wasteland, a ruinous place, used already by too many stopping motorcars and used most often to turn around and reverse one’s journey to to goal of our life-quest. We turn back to where we came from and make-believe it is the aim we always had, a belief reconfirmed, a place to re-read what we know and think we love it. Or if we read more, we read more of the same – that which fits the patterns of what we have already read and the beliefs it engenders.

That is the fate of those who wish to live in their culture and in that culture alone, denying the need to learn new languages or modes of communion like musical notation, for instance. Here I have to confess that I have always felt handicapped as a learner of new languages, afraid of the emptiness of a knowledge without context of its felt use beyond the everyday, that level of basic exchange of information. I want to learn them but rarely get far with them. It is a limitation that is only very thinly compensated for reading translations for much of what would develop one’s sense, and thought and feelings about the world described no doubt gets translated out of them.

The most resistant reading for me, as with so many in the West, is that written in the languages of cultures that have not been as interactive with Western and sometimes Judaeo-Christian tradition. For these are books with a very different frame of reference and reading framework. It strikes me that, at this point, we may perhaps think this is not the case with the work of Naguib Mahfouz, for after all he was the first Writer in Arabic to win a Nobel Prize for Literature. He is, moreover, often read in terms of the themes and structures of Western modernist novels: the names of Kafka, Sartre and Camus being prominent. He has been attacked as being anti Islamic by fundamentalist believers, stabbed in the neck four times on one occasion in the street for his supposedly pro-Western views.

But be that the case or not, I did not find my first novel that i have read of his to feel like the stuff I usually read. I suppose my thought process before attempting one of his works , though rarely admitted to myself, was that to read one was to open a door or something that might not stay shut; instead it might require me to acquire a deepening and widening of my knowledge of things yet unknown to me that I have been resisting resist. Fearing to read is often like this. Maybe I fear failure to comprehend what I think applied measures of self-worth suggest to me I ought to be able to comprehend.Indeed, I think it true that most of us fear both failure and being, as it were, overwhelmed at such portals to new reading. A good theory of education, for instance, would see that as the key barrier to children learning (a trend John Holt first mined in the book How Children Fail (1964), a must-read book for me at grammar school). We refuse to enter into even informal learning contracts, that is, rather than take a risk of failing or dropping out. One person I once knew expressed it succinctly: ‘I have never been interested in that s…t anyway’. At a stroke in such a statement, contact with that which is perceived as alien is stopped and we shrivel back into our own s…t, which is at least comfortable and warm, and smells somewhat like we do.

With this in mind, I was confronted in the remainder stock in Durham Waterstones bookshop the other day by two Mahfouz novels. Could I continue to resist? After all, they were not in Arabic, need not then be read from right to left and bottom to top on the page and hence nothing in the language it used need challenge. Indeed these American University in Cairo editions even had a glossary of terms I might not know, such as waqf, which comes up in the first page or two of ‘Heart of the Night’, and refers to a principle in Sharia Law, in which private wealth and property is willed as charity to the needy.

Other terms would follow referencing cultural traditions unknown to me. This happens in the Anglo-Indian novel too, in Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy’, for instance, when contrasting Muslim and Hindu traditions are pitted against each other. However, somehow Seth (great novelist though he be) does not challenge me for somehow his writing always explicates what we need to know in Western terms, unsurprisingly in a nation so mangled by the Raj and it’s oppressive insistence on colonising even the languages of cultures on which it imposed itself by trade, governance, law and ultimately value systems.

The strangeness of my first Mahfouz’s novel was then not in concepts that can be explained by a glossary but by differences in basic elements of the form of narrative and character building and expectation. I saw parallels in some Anglo -Indian writers I liked as well as of course in the Existentialist tradition to which it is claimed Mahfouz ‘belongs’, but none of this made this story easier to absorb into what I know already. Mahfouz, even in a brief story such as Heart of the Night was pushing on cultural boundaries that were deep enough to feel the stuff of personal and psycho-cultural development. In brief, though I didn’t WANT to go on reading it, or more and more substantial of his novels, I felt this was something I had to do, interested in his s…t or not.

In this novel was a portal, the entry into which would make me face the still liminal in me, that which should develop into new learning but is resistant to do so. And, if there was a time for Westerners to grow into more understanding of the cultures derived from the family of Arabic languages, it is surely now, as the West promotes the destruction of Gaza and, at the same time, the death of Palestinian cultural tradition As Najwan Darwish, that great poet favoured in Britain once by the great international socialist soul, John Berger, recently warned (see the article at this link). Whence this strangeness, this challenge. I feel?

The strangeness and queerness of the issues is definitely not I think a issue of the place or location of those novels, presenting themselves to me as an alien space. The novel certainly hugs to itself locales Jess well-trod by contemporary ‘Western literature ‘ but Bab-al-Akhdar alley is certainly not unlike the London locales made to seem shady to more comfortable readers by Dickens in the nineteenth century.

Bab-al-Akhdar alley fell into silence under cover of night. It is then that the hordes of beggars return to their spots, the lunatics clutter the corners, and the smell of incense fills the air. No outsider roams there at night except the few customers of Café Wadud. They are all hash smokers.

Naguib Mahfouz Heart of the Night (trans Aida A. Bamia, 2011: 9), Cairo, The American University in Cairo Press

The mechanisms in this passage (at least in this translation) for indicating to the reader that this locale is liminal to a favoured self-conception are the same as those in classic Western novels: the obsession with cover, silence and the night. Even the minimal population of the locale restricted to those ever-so-slightly queered so that we reject seeing our likeness there, at least in public. We are outsiders given a glimpse of an inside thought unknown to us., a Hyde to our Dr. Jekyll. All that is familiar to me in the passage. Even the class issues ring a bell. The story is an extended dialogue between a rather precious and over-familiar middle-class and professional male narrator, at his desk facing a man known to him in the past as someone of social consequence but now sadly reduced in status, whom he calls Khan Jaafar. The man brindles even with pride to be singled out as not a commoner but a sheikh. It is a ‘proud tone’ in dissonance to, as the narrator says, with the man’s ‘miserable look.’

He proudly introduced himself, though he did not need to. “Al-Rawi. I am Jaafar al-Rawi, Jaafar Ibrahim Says al-Rawi”.

ibid: 1

The idea of a proud family name reduced to a pathetic present instance of it in a wretched looking beggar feels like what we see often in the nineteenth century novel in the West, in Balzac for instance. But get that character talking, as the novelist does, and he becomes much stranger to me, a figure I can’t place in my reading experience even vaguely, except, as we shall see, in certain experimental episodes of his life. Indeed I think he is so in order to filter the strangeness of Jaafar through a mirror looking for the conventional that is the narrator. He is a device common to the novel that touches on the Gothic queer, like Mr. Lockwood in Wuthering Heights or Utterson in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

But Jaafar is different. He resists classification. Of course so do some Dickens, Balzac and Zola characters but consummate Western novelists, such as they are, always tie them down eventually, even Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights. Vautrin is the classic example though. Jaafar accepts no category. He doesn’t, he claims even have a childhood, de rigueur for the Western bildungsroman, the closest to the genre of this book, but instead a ‘time of legend’. The narrator wants quickly to re-insert his subject into the conventions when Jaafar says this but fails, glamorously:

“You mean your childhood years,” he said.

He was quick to respond. “I mean what I said, so do not interrupt me. There is no childhood, but a dream and a legend, the age of the dream and of the legend. It forces itself on you in a tender and possibly deceitful manner, usually because of the hardships of the present. It echoes strongly in my psyche, but when I analyze it I come out empty-handed, which confirms its illusionary nature. …

ibid: 9

This is not merely the failed self-making of a Gregor Samsa in Kafka’s Metamorphosis, as a salesman of fabrics born to the role (see my blog on a dramatisation of this novella at this link), but a developed redrawing of even the categories by which self is determined, assessed and evaluated, of which childhood is the central concept. Imagine, for instance, there even being a post seventeenth century literature in the West with characters who rejected this category: no Jane Eyre, David Copperfield, or Portrait of the Artist As A Young Man, only to mention the more obvious examples where the period of the narrator childhood is itself recounted to us.

Jaafar cannot conceive of a determination of what he is without seeing the category of determination as ‘illusionary’, something born out of the psyche post-priori rather than pre-priori, the stuff that is fabricated in lieu of memorial history, legend. This is not, I believe, the way in which existence precedes essence in Sartrean existentialism for their choices determine what we become. Jaafar insists, in a way for which I know no equivalent in Sartre, de Beauvoir, Camus or Genet that he has a right to a story that is ‘so mattered in the stream of thoughts’ that it risks his listener and the reader saying that of themselves that they are losing their ‘wat between its fragments ‘ (ibid: 10).

And again this is not the fragmentation we see in Joyce’s Ulysses or Woolf’s Between The Acts, which precedes from a modernity that has lost the authority of a monitoring and regulating and all-creative authority in either God or the Author, now both dead in Nietzsche’s and Roland Barthes’ terms respectively, but because Jaafar can say, “I hate restrictions” (ibid: 10). in brief, if Jaafar does not tell us something about himself, that thing does not and never did exist. This insistence may be close to Keats’ idea, attributed to Shakespeare, of Negative Capability:

that is, when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason—Coleridge, for instance, would let go by a fine isolated verisimilitude caught from the Penetralium of mystery, from being incapable of remaining content with half-knowledge.

John Keats writing to his brothers in 1817 cited https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Negative_capability

Jaafar too tells his listener not to look for certainties about past events because; first, he has no authoritative knowledge of them, being then a different being to what he is now, and, secondly, such searching for certainty will ‘crush inspiration’ (ibid:11). This may be the world of Scheherazade but it is not that of the Western narrator, as modelled, say, by Goethe, or even Henry Fielding. Jaafar only needs ‘an attentive listener to his story’. Once attained he is the only ‘sea of knowledge’ that matters .

“There is no ‘truth and fiction’, but different kinds of truth that vary depending on the phases of life and the quality of the system that helps us become aware of them. Legends are truths like the truth of nature, mathematics, and history. Each has its spiritual system. …”

(Mahfouz op.cit.: 12f)

As I start reading this, I alert myself to label the speaker as a relativist, believing in no absolute truth but only one fitted to the means of explaining and exploring it as in Western Modernist thought, but I think that would not be a correct view of what we have here. Jaafar is not interested in the sum of relative truths, however discordant and fragmented, as Virginia Woolf, T. S. Eliot and James Joyce are in respective modernist works, but in the truths that are visited upon those ‘predisposed to believe ‘ in them by the djinns in which they are being asked to believe. Such truths are not available for all or for all time, because djinns do not stay with anyone for whom the ‘legend’ has been accomplished and is now complete. They disappear at the ‘end of the time of the legend’ and their subject forgets them. If they see them again, if at all, it is only as incarnated in ‘new images of human beings’ where they ‘commit serious evil and cause great harm’ (ibid:15). If this is true of djinns it is more so of the Paradise, in mundane and supramundane forms, promised to those able to envision the Power and Destiny promised by Allah on Laylat-al-Qadr (the Night of Power or Destiny). Those all this might be traced to Muslim theology, it is not orthodox as the narrator continually reminds Jaafar. For their many contributing factors to the ‘legend’, though primarily located in a mother’s love, including, ‘for a specific time only’ sex, which Jaafar insists he experienced in a covered box at the age of six (ibid: 16f.).

All of this background to this character, self-created by powerful and totally subjective versions of mythical interpretations of religion, family and community is given to us before the beginning of Chapter 4, where we learn of the ‘timely and progressive’ views of a father Jaafar does not remember (ibid: 26), which (together with an authorised marriage) caused a rupture from Jaafar’s ascetic grandfather. And his father’s liberalism may lead to Jaafar’s choice of a kind of communal socialism that ends his own effective ability to achieve status in either the world of Eastern religions, governance or capitalist enterprise or even sexual adventure. I is here that Jaafar becomes most like the kind of existentialist that Sartre recognised – a person reduced to his CONSCIOUS choices in the world and engaged in them as a commitment to assert the authenticity of these choices. Having discovered the ‘world of the mind suddenly’ it fascinates him, in a way that excludes all other pragmatic considerations or desires arising from who-knows where, let’s call it the unconscious. Jaafar admits there may be an unconscious mind as Freud postulates it (a ‘submerged mountain’ under the tip of an iceberg) and that it may be large but less significant than the CONSCIOUS MIND because the ‘question is not a matter of size but value’ (bid: 74). The following is classic existentialist humanism:

Les Mots (The Words) in Arabic translation.

“Freedom is like an adventure. You practice it sometimes, for the enjoyment of the instincts, the way I enjoyed Marwana’ (his first wife, a ‘genius in the games of the body’), wine, and narcotics. But that is slavery masquerading as freedom. True freedom, on the other hand, is an awareness of the mind, its message, and its objectives. it consists in determining freely the means to be used, and organizing them meticulously in a manner that causes them to act like chains. It is therefore freedom masquerading as slavery.

ibid: 75

I have no doubt that this is a take on Sartre’s view of existential choice but almost, as it were, in parody, reducing freedom and slavery to mere counters in the mind. Just like ‘legend’ existential psychology is a doctrine that suits the time, ignoring djinns or the Freudian Unconscious at its own peril. At the end of his story Jaafar tells of his ‘sacred mind’ being ‘shaken’, as he ‘fell victim to mysterious brooding emotions’. Furies like these have little or nothing to do with Existential Choice. In speaking of it as ‘tragedy’ he assimilates it into a framework that existentialism fails to comprehend, but then neither does Western tragedy, which forever looks for some compensating principle such as Aristotle’s notion of catharsis. Oedipus at Colonus ends with Oedipus removed to some subterranean or ethereal distance, In The Oresteia, the Furies translate into the Eumenides and become the guardians of a homecoming. How does Jaafar begin and end in this novella. In Chapter 2 the narrator ‘asks Jaafar ‘how he lived’:

His answer was quick. “I roam the streets during the day almost till midnight”.

“Where do you live?” I asked.

“Among the ruins”,

ibid: 5

At the end of the book we have come full circle through various means of evoking the meaning of the nothingness of life, from legend to existential choice. He returns to his grandfather, Al-Rawi’s , palace, where after his mother’s death, he spent his youth. Alienated from that authority and its contingent wealth and socially-embedded spiritual and worldly status, Jaafar pursued his own adventure, its outcome, a return to his grandfather’s palace, ‘destroyed when a bomb fell on it during one of the aerial attacks on Cairo, and the rubble had been cleared out’. And, at this ending, Jaafar can say:

“… This is the whole story from beginning to end. … I also decided to set up house in the ruins of my grandfather’s palace. There I sleep, usually between dawn and forenoon, like any beggar.”

ibid: 97

That is not quite the end, for the narrator insists on trying to eke out of this story some compensation to find that Jaafar will do nothing to improve his personal circumstances, though it be ‘madness’ as the narrator says, it is, says Jaafar, a ‘holy madness to the last breath’. And there is the nub of the queerness of the whole novel. It is not only the lack of compensating meaning or emotion or both (for, after all, a catharsis is both) but that in the end, we are told that all we have left is ‘silence’ and the possibility that the only meaning of that silence is to hear another story in another place until we can hear no longer because we have died.

There was silence. He was a tired storyteller and I was a tired listener. I yawned.

ibid: 98

There is, should we say no other function to telling and listening to stories than to tire oneself out and fill the time until the next one should be told. A novel that ends with: ‘My head was ringing with the talk of the night’ (ibid: 99), takes us back to the tradition of Scheherazade, telling and listening to stories solely so that the storyteller survives to tell another. The Heart of the Night is such talk. It is why reading is a ‘vital necessity’, for it shows that neither fixed beliefs nor making existential choices will achieve any real difference in the world, other to confirm to the West what it already knows, that it dominates everything. If we want to escape the ruins, we must stay in them, as the people of Palestine are currently being forced so to do, until humanity realises that it must rise up in common : Jaafar’s only message is to ‘invite humanity to save itself’ (ibid: 98).

Now that is a writing I must read and go reading. Mahfouz wrote at least 40 novels and lots, lots more short stories.

I hope you will read him with me.

With love

Steve

One thought on “Do I really ‘want’ to read more books by Naguib Mahfouz? The psycho-cultural limitations in creating and destroying the desire to read & the ‘vital necessity’ of reading.”