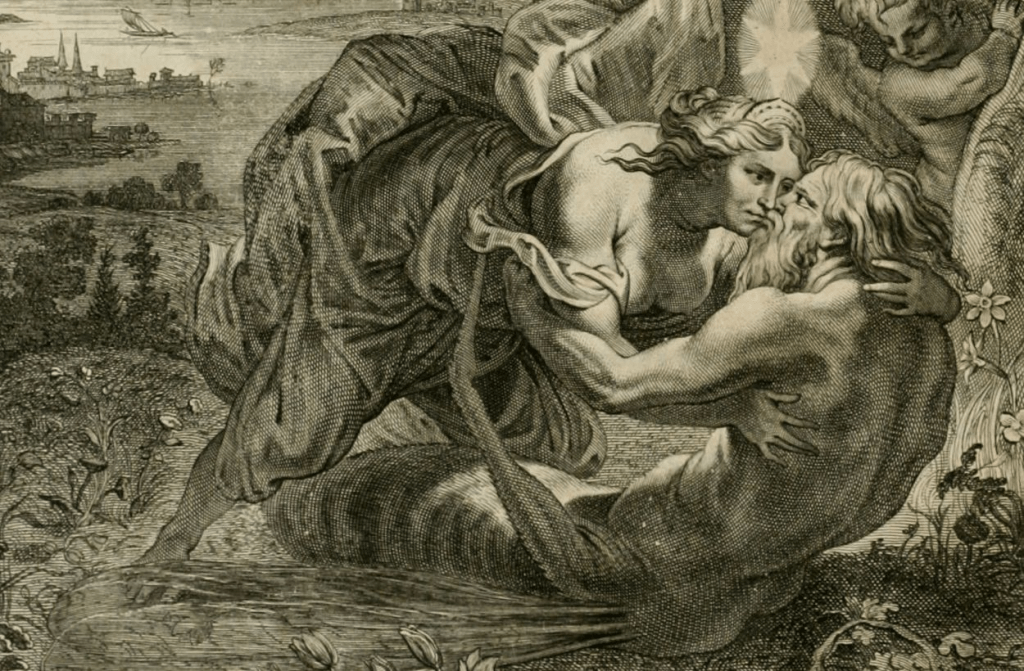

Okay, said young Tithonus, to the goddess of the Dawn, as she senses that this boy has prominent qualities that make him worth the effort of capture – ‘but as long as I can live forever’ he says. At which the Goddess possibly smiled. Humans never work their wishes through do they?

Tennyson says it best, in a monologue supposed to be spoken by Tithonus, a man granted his wish for immortality by the God of the Dawn, whom he loved. But while the God recycles her life with returning fresh beauty each morn, he is like something that, though he cannot die, cannot live except as a grey shadow:

Here at the quiet limit of the world,

A white-hair’d shadow roaming like a dream

The ever-silent spaces of the East,

Far-folded mists, and gleaming halls of morn.

Alfred Tennyson ‘Tithonus’ full poem at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45389/tithonus

It is an intensely morbid poem, that is really (I think) about the fact that the excitement young people associate with love as we saw it in our youth dies and what returns daily with the morn and seasonally with the the spring threaded through it feels to be a gift bestowed only to others still vital enough to receive it.

We could though, couldn’t we, allow love, and the concept of it that we have been used to hug too tightly to our bodies, to develop into relaxation with that body into something durable. Instead we despise its wrinkled maturation. We long for the excitement in the blood and on the feel of young skin reflecting in that haptic moment the sense of our own body’s ability to merge wit healthful flows of its fluids. what we thought to be our own but what is a mere rite of passage. Tithonus revives the moment when he felt love as a motion in his body, a time wherein he had:

……. felt my blood

Glow with the glow that slowly crimson’d all

Thy presence and thy portals, while I lay,

Mouth, forehead, eyelids, growing dewy-warm

With kisses balmier than half-opening buds

Of April, and could hear the lips that kiss’d

Whispering I knew not what of wild and sweet,

Like that strange song I heard Apollo sing,

While Ilion like a mist rose into towers.

ibid.

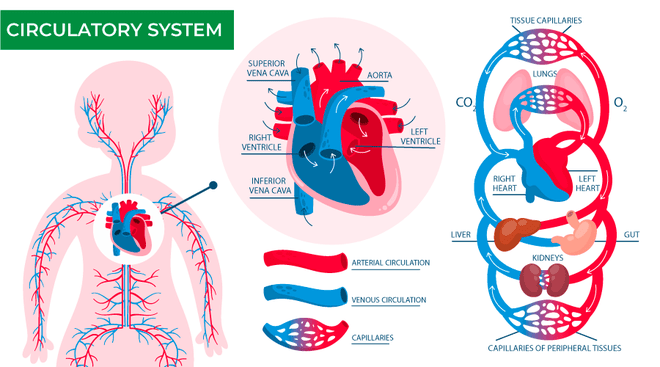

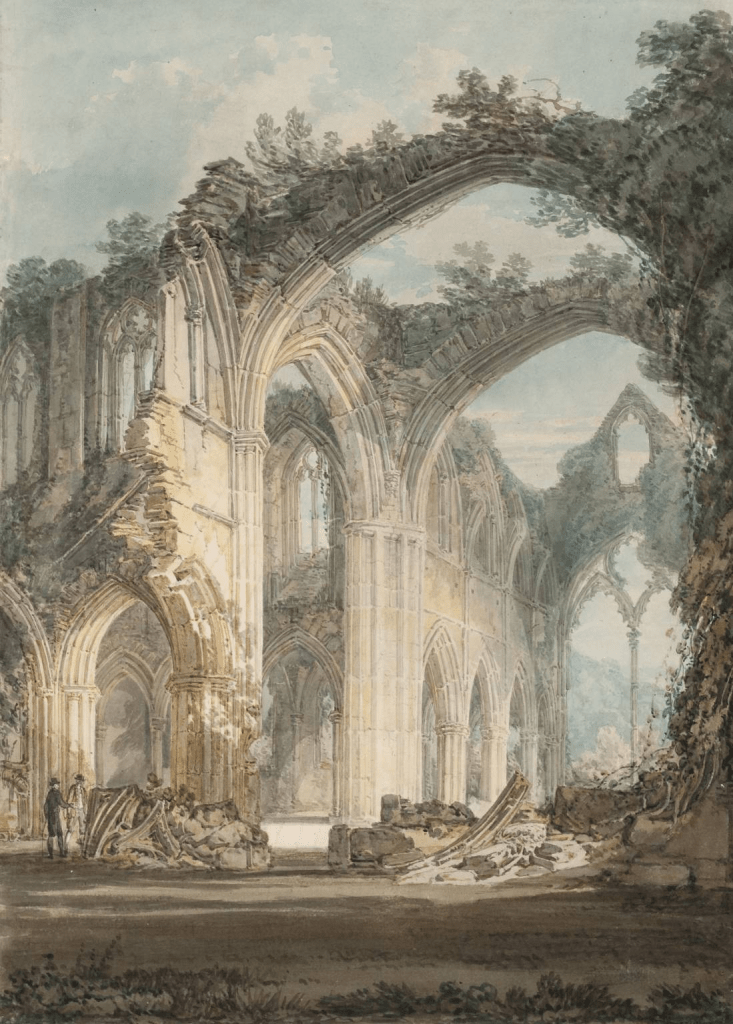

It’s a lovely dream, but a dream nevertheless. And it’s odd how we strain to revive it as an animal species – finding the apex of our creativity in that flow of music that echoes that in, Wordsworth’s terms, is ‘Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart’. I will never forget the moment when A.S. Byatt (the lecturer we knew as Mrs Duffy, who taught me both poems (the second is of course those Lines Composed A Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey), pointed out that the beauty of those lines lies in the surprise contained in its prepositions – for conventionally we feel things IN the heart and our blood beat ALONG our veins pumped by the organ into a varied music of changing flow. By making the feeling inhere IN the blood, is to make it part of the flow of time, that has extension only in physical space not time withing the body’s recycling of it by the beating heart – the heart in the line is lengthened into the coils of arteries it animates itself along.

But the point of that beauty is that the ‘sensations sweet’ are, as Wordsworth defined poetry itself in the Preface to The Lyrical Ballads, the ‘spontaneous overflow of powerful emotions’ in which the body is implicated, but as ’emotion recollected in tranquility’. Wordsworth accepts change and growing up, and even the loneliness and loss with which we associate our past, provided we don’t accept that ‘tranquil restoration’ isn’t the past relived but just the past given back to us as something we use to regain our own embodiment IN THE PRESENT TIME (our presence literally) and not scorn it, as something LESS than we used to be.

But oft, in lonely rooms, and ‘mid the din

Of towns and cities, I have owed to them,

In hours of weariness, sensations sweet,

Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart;

And passing even into my purer mind

With tranquil restoration:

William Wordsworth ‘Lines Composed A Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey’. The full poem is available at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45527/lines-composed-a-few-miles-above-tintern-abbey-on-revisiting-the-banks-of-the-wye-during-a-tour-july-13-1798

Nothing about Tithonus, is tranquil or even collected. He wants to feel that blood flow he felt in his youth continue beating as it once did, prompted by his touch of the skin of another that flows into the sensations of his own limpid and flexible skin that he almost re-feels in desire, for this desire is very reflexive desire. But it doesn’t. It flows cold along the wrinkles as it were, by Wordsworth are not relived over and over, extending those sensual excitements forever into the long more abstracted spaces of eternal time, as Tithonus hoped they would be for him. And, after all isn’t there something a bit potentially repulsive in the ‘dewy-warm’ and sticky that Tithonus wants back, and something that is desirable in that condition Tithonus himself seems to be a terrifying one:

Coldly thy rosy shadows bathe me, cold

Are all thy lights, and cold my wrinkled feet

Upon thy glimmering thresholds,

Alfred Tennyson, op.cit.

There is a coolness here worth appreciating in these sensations of comparative cold. Youth no longer seduces those accepting of age for it returns to the seductive bathing and glimmer a self-sustained that says ‘I have become what I am’, and own it, wrinkles and all. I think Tithonus deliberately shadows the influence on it of Wordsworth’s lines above and merely reminds us of the extremities of the human ability to rail at the fact of aging, confusing and confuting it with the ‘barrows of the dead’, for with Tennyson, that youthful dawn was I think his young love for Arthur Henry Hallam and the youthfulness not only of their love but of the ideas of a new beginning i life and society both were inspired with by that love. Tithonus loved Eos, the Dawn, and when in In Memoriam, after Hallam’s death he thinks he is destined not for dawn and renewal but the Evening of his life, represented by the Greek God, Hesperus (equivalent to the Roman Vesper – as in this poem), as if evening had already faded in the Day’s END:

Sad Hesper o’er the buried sun

In Memoriam Lyric CXXI. Full lyric available at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45354/in-memoriam-a-h-h-obiit-mdcccxxxiii-121

And ready, thou, to die with him,

Thou watch est all things ever dim

And dimmer, and a glory done:

In this little first stanza of Lyric CXXI is near the end of the series of poems and Tennyson has grown and developed, When he remembers Hallam by this time, he still does so as if he were Eos (the Dawn – Tithonus’ lover) or Lucifer, the Morning Star as honoured by Blake but to which he gave the Roman God’s name Phosphorus:

Bright Phosphor, fresher for the night,

By thee the world’s great work is heard

Beginning, and the wakeful bird;

Behind thee comes the greater light:The market boat is on the stream,

ibid.

And voices hail it from the brink;

Thou hear’st the village hammer clink,

And see’st the moving of the team.

Those lyrics rhythmically perform the music of endings and beginnings respectively, but this poem is decidedly not one ending with a Tithonus like weariness of life and longing for the grave, which, I think, he wishes his lover too were buried in but with the recognition that Hesperus (Vesper) and Phospor are one and the same star (Venus – love of course):

Sweet Hesper-Phosphor, double name

For what is one, the first, the last,

Thou, like my present and my past,

Thy place is changed; thou art the same.

Ibid.

The Morning and Evening Star in masculine version chase around this pediment to prove their sameness

The echo too here of the Alpha and the Omega ( ‘the first, the last’) of the Judaeo-Christian God is a means of reminding us that age is just a change of place in time. Of course, it is up to us with what we do with that new place, and release from its ‘ever-silent spaces’ such as those Tithonus thinks of in his age are filled with somewhat of beauty, though the flow of blood and sound will be different, heard in the joy of more distant pleasures in the mellow, the mature and even in the beauty of stilled decay as in seventeenth-century still life (see a blog on Spanish still-lifes this at this link).

With sad but sure and solid love

Steve xxxxx