I recently blogged on the work of the brilliant Matt Colquhoun as it touches upon and works with the thought of his no less brilliant deceased mentor, Mark Fisher (see it as this link). I summarised the view they both promote and which Matt is consciously developing apace now, that the left of UK politics:

… needs to recognise that unconsciously, it too is often locked into a paradigm of hopelessness attached to a lost world of simpler relations of production and consumption, of a visible ’bourgeoisie’, or ruling class, on the one side and a proletariat and lumpenproletariat aware, by virtue alone of their place in the economic system alone, of the need to rise against capitalist distortions of human value, were it not for their ‘false consciousness’ alone.

From (the text is revised a little): https://livesteven.com/2023/12/13/this-is-a-blog-on-understanding-why-there-is-an-impersonal-and-public-politics-of-variations-of-intimacy-in-relationships-and-attachments-that-feel-private-it-is-also-on-why-this-blogger-feels-inadeq/

Is it possible I think that my politics likewise is sometimes stuck in a paradigm that is hopeless and lost. For I start to rethink things, with the help of the young creative left like Matt in a way that rebuilds politics from a radical 🌈 rainbow coalition of the erstwhile marginalised but often reflects back to the origins of my beliefs in working class experience. I don’t intend to fight that tendency in this piece but instead wallow in the past, in stories of the working class identifications that keep me ‘forever Red’, perhaps even to the grave.

It might still be possible to say, that I haven’t changed my politics but that would only be true of the broadest brushstrokes of an answer, for I still identify with the red flag of the British left, however embarrassed of it through its history during my lifetime and in stories told below became the UK Labour Party. But that wasn’t because my working class roots were, as in the case of Owen Jones, politically conscious ones from the left of politics. Though brought up for most of my young life on council estates, if not born at either (for that was at Halifax General Hospital) and we returned to live in a dilapidated old weavers cottage overlooking Holmfirth and the Holme Valley, it wasn’t assumed by the early 1960s, in the West Riding of Yorkshire, that even voting Labour was a certainty for the working class people I mainly knew.

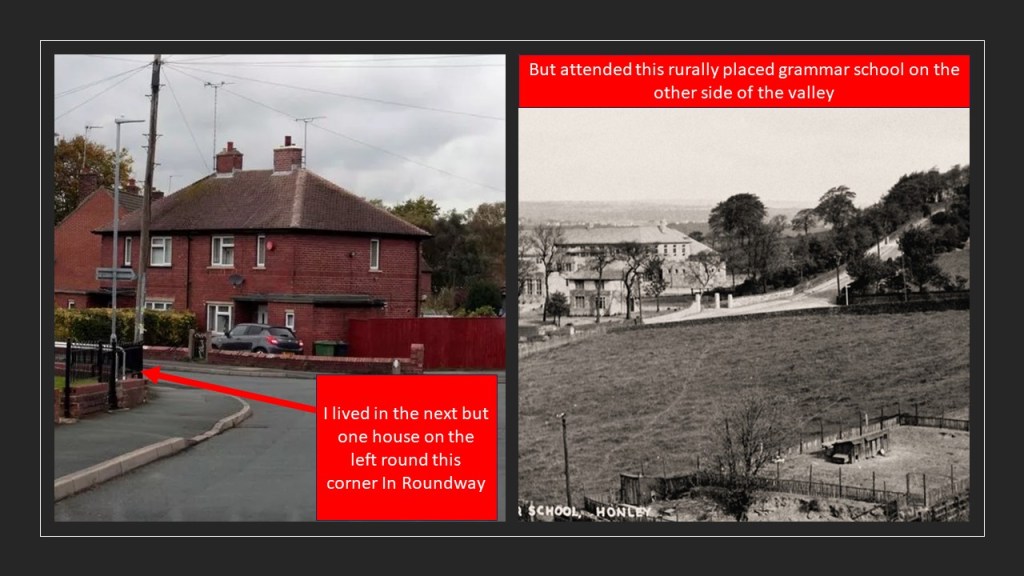

Indeed, very little I knew in my young consciousness could even be called ‘Swinging’, for by the time I had such a consciousness of politics in the 1960s, I sort of drifted into the best kind of liberal rather than radical, individualist traditions of the North rooted in free trade consciousness really. Our MP was Liberal but orientation around political party wasn’t seen as an option. Neither of my parents had political affiliations and I remember being shocked when they bought their council house under the Thatcher reforms, for by then, living in the Roundway estate (rather notorious in parts) in Honley (near though to the grammar school I attended) I had identified as socialist and read The Guardian. Of that later.

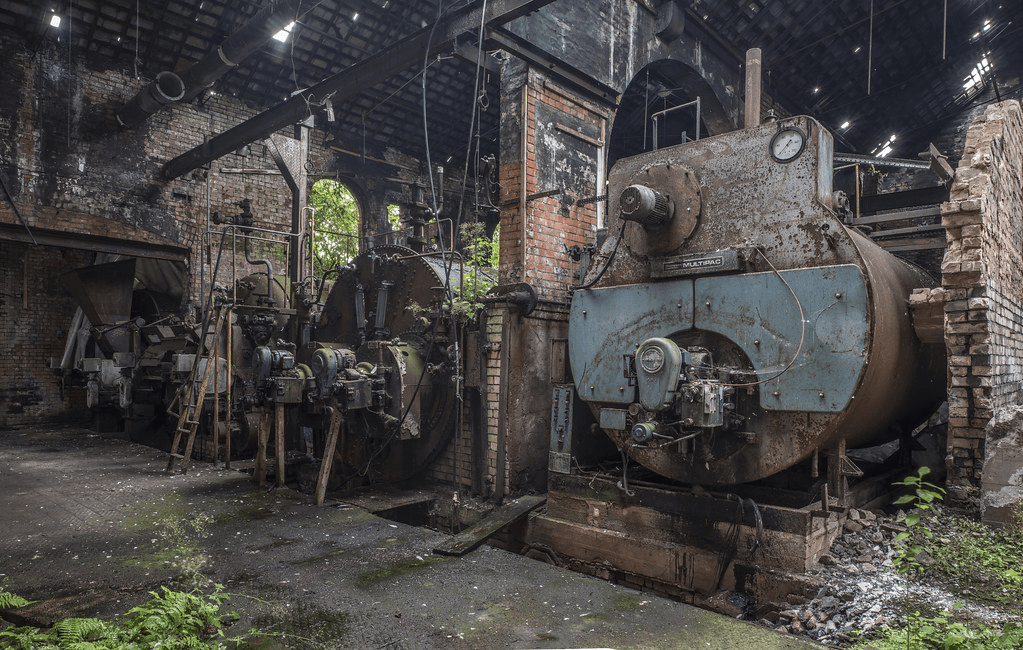

My main political memories of childhood and those which tested the then obvious class base of Liberal (and Free Trade) politics are those dealing with knowing and reflecting on the lives of my grandfathers. Both were shadowy figures to me as a child, men who came home late whilst one or other of my grandmother’s cared for me so that my parents could have long nights out unencumbered and drinking through the illegal-after-hours of pubs then with their friends. Each of those grandfathers came home drunk – on a range from what they called ‘fresh’ to a name they couldn’t say for they were incapacitated. The grandmothers both fumed in their different way. But I got to know them better, though it was to my maternal grandfather attachment belonged because he took me to see his work places, when they were, in series, places at each end of Salterhebble Hill at which he worked one after the other: first at the sewage treatment plant at the bottom of the Hill but more excitingly in the boiler room of the Halifax General Hospital, at the top of Salterhebble Hill.

So the first political steps are told in, and we can start with it, a photograph.

The tale of Two Grandfathers

The places in the collage above were my grandparents’ environments and were in my mind equated with them. I would travel to them in the back of my dad’s work van together with paints, turps and folding ladders, for we lived then in Woodlands, an estate between Holmfirth and Honley or New Mill, depending on your route of travel. By my conscious childhood, my paternal grandparents Elsie and William (known to all as Billy, though he was an austere and unsmiling man) lived in a house just a little further on on the cobbled back street of Holmfirth shown in the inset picture in the collage top left. It was behind the stone steps that led to the stone church yard of the Church of which you see the tower in the picture wherein also was Beale’s fish-and-chip shop, that became the site of the cafe used in that dreadful comedy series The Last of The Summer Wine.

My grandmother babysat for me there, as she did when she moved to a council estate after Billy’s death at age 61, in New Mill. But it is of Billy I speak. He was a slight and always frail man with poor health, who worked when he could for the council on the roads, a job he liked to attribute to the well wishes of a friend on the local council, but then he always seemed to beholden to the powers-that-be and never willing to criticise them, for Billy was as strong a working-class Tory as you would find. He canvassed for them and on every night attended the Holmfirth Conservative club – the picture top right in the collage is as near as I could get one for it, from the webpage of a Kirklees Council history website you can see at the link just above.

Conservative Clubs thrived, for in the North their cynical base was that of a patrician culture that believed in serving the nation with the best of old traditions that for them combined monarchy, partisan and unyielding jingoistic nationhood. tight law and order combined with a strong belief that the social order was the gift of an often Methodist God (with the voluntary subordination of poorer classes by quiet custom as its preferred method of implementation – much as in The Last of the Summer Wine) and Willy was a prize model for the patricians of the day ruling the Con club (for con it was though that was the name always used of themselves).

Willy lived and died in servitude, though he wore a pin-strip suit on his Saturday drunken sorties with an attached pocket watch and chain given to him by some Councillor (who employed him sometimes and used him to staff election cars as a knocker-up). When he died none of the Cons came to his funeral. No-one did but immediate family for he was an unlovable man. But his example taught me something that became subterranean to my later politics.

The Con Club was formed in 1869 by, amongst others, a bluff whisker-chopped, Walter Spencer Stanhope, who at one of annual dinners showing that this was not a group of one class said that he ‘believed that clubs such as Holmfirth would enable a Conservative victory to be achieved. He went on to say that calling the association a “club” meant that it: “admitted all persons of all degrees and all ranks and induced a feeling of good fellowship.” In fact it used the term ‘club’ because it had been previously owned by the growth of working men’s clubs affiliated to the labour and trade union movement. It was all so cynical.

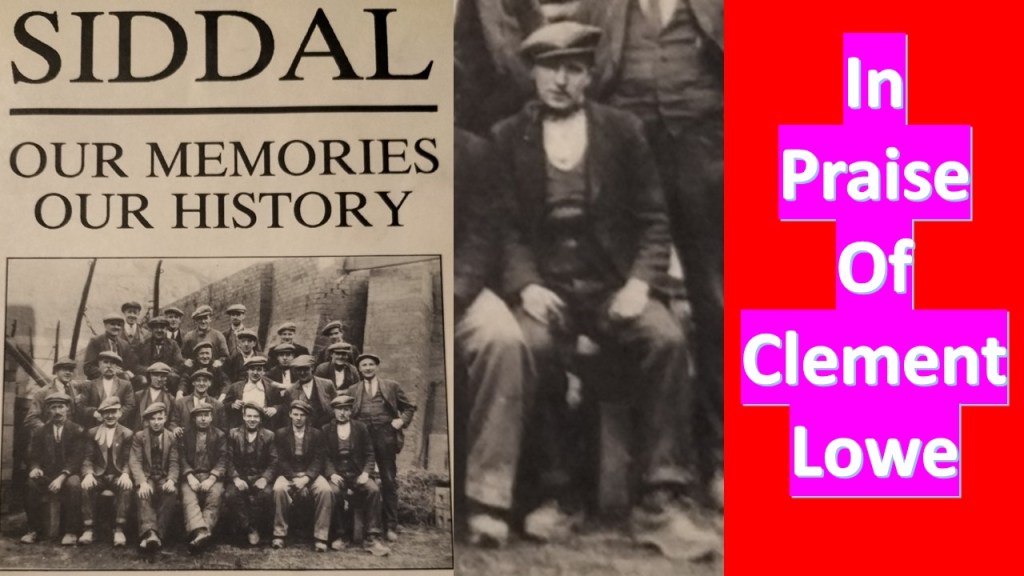

Before I knew ‘Clem’ as people called my maternal grandad, he had worked and lived mainly (but for a period in a council house in an estate called ‘Backhold’ (that eventually proved too expensive) in back-street rows of privately rented houses, employed first as a builder. A local history group unearthed a picture of him and his fellow workers that I will share with you:

This image, though seen in the flesh by me, is what really sparked my identification with the working class. Clem had no formal politics though he would talk disparagingly of ‘nobs’ up Skircoat Green in Halifax and voted Labour all his life. He also had a tinge of his own mother’s republicanism. I knew his mother too, Annie, a hard-drinking woman from County Claire in Ireland still replete with stories of riding a jaunting cart. But proud of work when he had such, he truly was, and spoke of the dignity of Labour, even when sober.

The picture prefacing this tale of two grandfathers shows Salterhebble Hill as seen from Siddal across the Calder Valley. In the base was the factory at Boys Lane my mother worked at and eventually Clem and wife, Aggie, of mining stock at Pontefract lived in a house at the bend of Salterbble Hill just behind the Falcon public house. I visited him at his work in the Sewage Treatment Works at the bottom of the hill, that you could smell all day in their home, as his fellow workers , as he called it, stirred it up. But my favourite trip was to the boiler house under the Hospital (I think under the Rotunda you see in the picture), the one at which I was born, down rickety steps: not a safe space for a child but things weren’t strict then. I remember the smell of oil and coal, the huge mouths of the boilers he fed and the hard muscular work. In the heat, like in the mines, men bared their torsos to the work. Now such places are ruins even in their mechanised forms.

Those images stay with me. They supported a growing sense of the marginalisation of the world of the many by the privileged few.

A grammar school boy gets a conscience and a visit from a Labour Membership Secretary

The grammar school was, as it was intended to be, a dividing experience. My first home was near the largest Secondary Modern, and passing it in the evenings, then still a frightened first form boy I was ripe for bullying. There was no bullying I remember at the Grammar School but I felt singled out in other ways for few others lived on council estates and when it became known that my mother was a cleaner at the school, it was, let’s say, treated as a subject of embarrassment, an embarrassment in my weak shame, I shared at the time. Except by O levels I was somewhat of a teenage rebel and had taken in the influence of admired teachers, such as my English teacher with the Cambridge Leavisite background with a Raymond Williams inspired socialism and a Marxist Workers Revolutionary Party (WRP) teacher, who sold their newspaper in Huddersfield, who taught History and Marx together.

The owner of the copyright of posters produced at the College of the ‘Beaux Arts’ later owned Brancepeth Castle near my home now, and I bought copies for our walls. But then I went to University.

A tale of an Emerging Labour Student & his part in the downfall of Baroness Jeger

I read The Guardian now with disdain for the right-wing The Express taken by my parents, who would say they didn’t think it was ‘political’. One day I invited the Labour Party membership Secretary to the house, for I wanted to commit, but not to anything like the WRP. The membership went through – in, I think, 1968, the year of revolutions in Paris and riots in London Colleges, including Southland’s College where I would later work, of which I began to become aware, and which excited me. ( I imagine Clem saying “call that Work!) with a kind smile, for as an older retired man he became gentle. He even visited with my grandma myself and my husband when we lived in Isleworth, and I was ward Secretary of the village’s Labour Party.

For me the ‘People’s Flag’ should still be red, but not even as nostalgic for our ‘martyrs’, though I respect them, but because it is the colour of blood and embodied passion – the heartbeat of renewal sometime, even after my death. I hear Clem say, as he often did, ‘Hey lad! Never bother’ and pushing a pint over. I don’t drink any more though.

At university I joined the Labour Group, although torn by friends who were members of more committed socialist groups, I was a fan of Michael Foot of course – a deeply literary bourgeois individual with sincere loyalties to the working class movement. But my university life was more absorbed by ‘coming out’ as gay, and campaigns took much more of my energies. Nevertheless, we had a left caucus, as we called it. Moreover, my dearest friend was a man I room-mated with, and whom, of course, I fell head over heels in love with. He was another working-class guy, whose parents knew Barbara Castle. We weathered that inequality and he married a school friend of mine and went to live in Holmfirth.

Of course, though we were in different Labour groups (me at University College, he at Kings), we canvassed together for the Labour, for Lena Jeger whom we met with her stiff comradely manner (straight from the Gulags some said for she had lived in the ambassadorial residence in Moscow) probably in her last election for the Commons and he kept me solidly in Labour. Not for Dave those who called Barbara Castle a class traitor for her part in the In Place of Strife legislation under Harold Wilson.

But as my labour militancy grew less, my militancy as a gay activist got more with the early Pride Marches in London, a torso festooned with badges (we still have them) everyday at College, where otherwise I was treated as a very serious student of Literature.

A tale of two handsome Communists and a loyal heart

The radical leftism came when I left UCL, and took up a PhD at Kings College Cambridge. In my rooms, a suite with sitting room and bedroom overlooking the tiny square across the street from King’s and beyond the shops, I held seminars for they gave PhD students teaching. My mentor was the King’s tutor and left wing radical Colin McCabe, and the group of undergraduates I became involved with, all living in the same block, were entirely left wing. Byron was the only Labour party member but was perhaps too into MANY women to allow me near him.

I did have a fling let’s say, that seemed serious at the time, with a guy of a Jewish East End family origin, though they had by then left the East End, who came out as gay and allowed me to kiss him, although not hold his hand in public. He bought me books of Marx and Freud, which I later learned he had not bought but purloined (it happened with students even in those days of full grants). We were as heavily into Communism and Communist History (I learned of the Cable Street Rising from him and his wonderful mother when I met her) as into love. Tel Quel and the French theoretical trends McCabe built into literary studies at Kings gave it academic credibility too.

Our relationship crumbled as I did at Cambridge, and I left after a year to go to Leicester to continue studies there under Isobel Armstrong and a quieter regime, except for the group of sociologists I befriended. They were mainly International Marxist Group (IMG) members – a more strictly Marx-Lenin-Trotsky inspired left grouping than WRP and more well-read in theory) except for one – the one that had read more than them all, though they were postgraduates and he a third year undergraduate.

Stunning masculine beauty was the first thing you noticed about Jim (the name changed of course), the second was his girlfriend – always there. When he spoke he knew every theory and its history in Marxist tradition. He seemed to know Althusser inside out. When I met his mother, who lived in Nottingham, I knew why. Here was another exceedingly educated family. Through Jim I joined the Leicester Communist Party having read The British Road to Socialism, which planned a transformation to socialism in time via the Labour Party, because of its wide alliances in the Labour Movement.

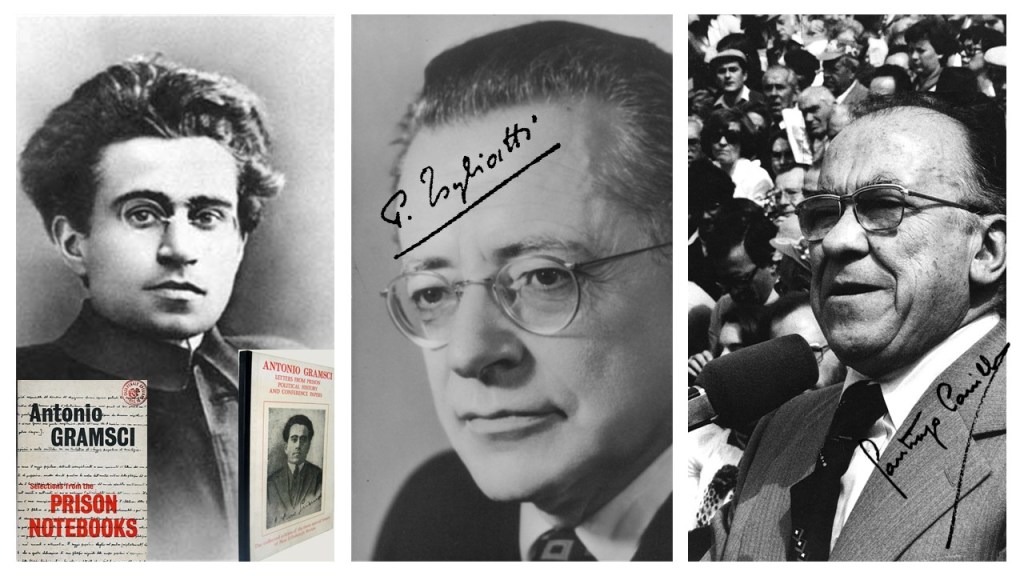

The British Road was, as far as I was concerned, a EuroCommunist document, mirroring the approaches of Togliatti of the Italian Party (PCI) and Santiago Carrillo of the Spanish Communist Party (PCE), both of whose books, which I read and absorbed, owed much to Antonio Gramsci, writing from fascist Mussolini’s cruel jails, and whose books (in the editions shown in the collage below) I revered.

Though the Leicester Party branch was full of ‘tankees’ (supporter of tough tank-led domination of the Warsaw Pact countries by tanks if necessary) Jim got me involved in Summer Schools run by Martin Jacques (the Eurocommunist editor of Marxism Today) and the Communist Universities, which took place in university buildings in the Summer and opened up Left thinking – attended from a wide range of traditions and a place of civil discourse and wisdom where the arts and sciences were both celebrated.

There is no doubt that I continued to be inspired by Jim’s good looks though he became a good friend of my partner, Geoff (now husband) whom I met at Leicester (in The Five Star Club introduced by a queer couple, who paradoxically two of the key ‘tankees’ in the Leicester Party and whose posters ranged from Liberace to Leonid Brezhnev). In the end the CPGB was wound up, perhaps it has done its job, or (more probably it could not sustain the pressure of people who saw the USSR as incapable of anything but virtue – which few of its people supported). During that time Geoff and I visited the USSR – doing the overnight train journey between Moscow and the then Leningrad.

Stevie, the Labour apparatchik, Internal Pressure Groups and a Conference Resolution

The Labour Party had always been my home though I was uncomfortable about the Militant Tendency and at the time, when I rejoined it, I supported Neil Kinnock’s harrowing of Liverpool Militants from the Party. At that time I was in Isleworth as Ward Secretary, following on from having the post in Brentford. Later, I was to be the Consituency Secretary from the offices in Chiswick then, a friend from Isleworth and a councillor, Vanessa, becoming the paid secretarial aide. Geoff and I became friends of Ann Keen, later to be the Constituency MP and in the Brown Government an Under-Secretary of State for Health. I devised newsletters and opened up communication, not to everyone’s joy to a wider range of opinion in the Party including the Left. Another friend of ours is still on Hounslow Council, Tony.

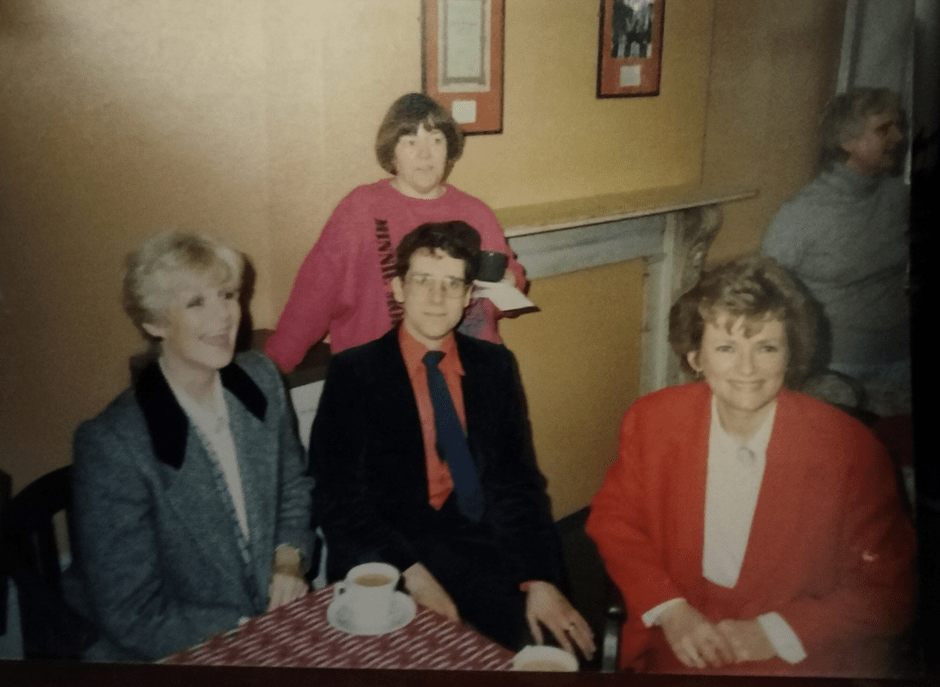

Ann introduced Geoff and me to Neil Kinnock in her Brentford home and he gave me a china plate from the NUM, given to him by Arthur Scargill, begrudgingly no doubt. Neil was no great friend of Arthur and I remember campaigning for Nick Rainsford in, I think, Battersea, with Stephen Kinnock, then a schoolboy, and a charming lad. Glenys visited the Constituency and its office (as in the photograph below where there is Ann, myself, with Vanessa behind me, and Glenys.

In many ways it was easier in those days to have a position that allowed for the catholic range of views on the left for, in those days, apart from Militant (with its separate organisation) people tolerated each other because they respected democracy even when they manipulated it, with the use of caucuses that met informally to draw up lists of preferred candidates – which then included people who have drifted far to the right and into the Establishment of the Party. It was possible for me to speak up with black and brown radicals who were labelled extreme left because they pointed out structural oppression in the Party, quite correctly and with truth on their side.

The rot set in when, as CLP Secretary (re-elected more than once), I successfully stood as Conference Candidate and went to Blackpool in the year when the link with CND was considered the sticking point for Labour re-election against Margaret Thatcher. At Conference also was Ann Keen, as Constituency Parliamentary Candidate. I took my delegation in votes and the CLP had voted to oppose any motion standing against support of unilateral nuclear disarmament.

Geoff came with me to Blackpool and we met the Kinnocks in the Grand Hotel with her (the year he fell on the beach – pulled over by Glenys he said). I was ill and worried. These were the days when HIV and AIDS were confused together. My symptoms seemed to be those of HIV infection . It was not till I returned home that I tested negative and the cause of my illness was traced to effects of smoking cessation. On the evening before the CND vote, Ann Keen told me she would be called to speak – though apparently without plan, and that she would support a multilateral option killing off the CND connection. I cannot forgive myself that I abstained on that vote because of my fear of it seeming that I did not support our parliamentary candidate.

The informal report that went back to the CLP meeting was antagonistic, though I had written a report showing how I had voted and why, and I was pilloried. Such is life. I was naive and you cannot afford that in the Labour Party. But it hurt and I took a less active role thereafter.

The past strikes back on common land in Cockfield: the story of a Secretary and Agent (failed)

By the time I became active again, my life had changed. In 1989, after 11 years teaching English Literature at the Roehampton Institute I began to tire of academia and became aware I would never finish my unfinished PhD on Browning. I felt like a medieval monk with acedia. In fact I was both depressed and anxious in ways that were out of control and had happened to me before when I left Kings College Cambridge. I moved into secondary school training – a mistake, for the stress was greater, and I didn’t sufficiently recover from my depression significantly until, I think, 1993-4, when I started a conversion MA course in Social Work. This was after working on a Diploma in Health and Social Care, and later building a Psychology BSc. degree at the Open University onto it and working during that time as Social Work Assistant for Older People in County Durham, first in the Dryburn Hospital as it was called then, dealing mainly with hospital discharge, and then in the City. I finished my Training in, I think, 1996 at Durham University.

During the earlier part of this time Geoff and I lived in Hamsterley Village, but there being no Labour Party organisation in the churchy wealth of that village, we joined Cockfield branch where I was soon ward secretary again. Eventually I acted as Agent for our candidate, though his chances were not high and he did not win.

At the time, perhaps, as a result of personal crisis, I had settled into a kind of Labour centrism as an antidote to the poison of Thatcher’s government, To tell truth I was more near a Blairite before he became Prime Minister than I knew. And despite the belief that the Durham Miner’s Gala is a symbol of the Left (natural home to Arthur Scargill and Jeremy Corbyn who were once each cheered more than others) the tradition and talk of Durham miners does not suggest radicalism.

The Blur of Blatcherism and Corbyn as Messiah (true and false)

Nevertheless the Blair government, when it came, was a shock and I considered my position many times. I could accept the economic prudence arguments of Brown and I believed the aim was a sounder foundation for socialism but the belief in the rightness of privatisations as a source of public financing worried me (as the Public Finance Initiative – PFI – in the NHS should have more so). Yet, as a social worker and later social worker teacher (at Teesside University) I accepted the rightness of the private elements necessary, it was argued, to create an economy of choice for service users of social services, though again as systems collapse – services collapse in the private sector first because public wealth has withered in the interests of private wealth.

In foreign policy, I was the more concerned – the support for global markets and the liberalisation of stock markets, the loosening of state regulation generally – went with support of arms buyers on the international scene who were the very forces under which ordinary working people and the otherwise marginalised (such as people with disabilities) of those countries suffered. I began to return to earlier reading of Gramsci and began with the New Left Review to identify a force in global politics better know as Blatcherism than anything else.

Foreign adventures became a trademark of Blairism but I stayed within what we used to call the Broad Church, though quietly delighted that, under a democratisation of the party I had long supported, allowed the election of Jeremy Corbyn. Far from an extreme left radical the policies of Corbyn were for me a breath of fresh air. Of course, they depend still on that great lie of the rich capitalism nations that ECONOMIC GROWTH is the path to affording fair and equal social policy, diversity with equality. This is the guillotine that may yet face a Labour Government under Starmer or even in an election campaign.

I could not stay in the party long after realising that Starmer would not explain why he but not other candidates could afford to send posters of his face as a manifesto in the Leadership Election, though people coughed and spoke quietly of the Blair Foundation’s wealth. Now, I cannot face the erosion of policies as soon as they prove ‘unpopular’ without them ever being explained – such as initiatives for cleaner cities or regulation in the interests of environment. Above all the fallacy of the growth argument as a priority as if it would have no consequences on environment o the gap between rich and poor in essential development resources. including education. As an election approaches it is clearer that immigration and culture wars will be weaponised, and, as in the many elections fought by Harold Wilson, provide the parties with a tasteless race to the bottom of human values and the encouragement of all diversities.

The faithless children of Blatcherism and their narcissistic rhetoric.

Recently I have used social media and on Twitter in particular Brexit (a terrible policy proposal in my view) created on there in particular groups of remainers and leavers still fighting it out years after Brexit has become a fact These people included a forceful group of people born in the 1990s, whose only knowledge of Labour was under Blair’s New Labour and for whom the Third Way, promoted by Anthony Giddens for Blair, was a catchword. After Brexit, they seemed to morph into the name they preferred, ‘centrists’, as if this were anything but a metaphor.

The priorities change for a socialist without a party.

I even became closely attached to one such (in love in fact as my husband tolerated it – loving him too). However I was soon to learn that the catchwords of Blairism – realism, pragmatism and the lack of tolerance for things decided to belong to the past, even loyalty and openness – were in fact at the subjective core of this group. Leaders knew better. They accepted subordination as a natural effect of Blairite meritocracy and thought it fine to develop policy silently and with the use of necessary casuistry – which to some of us seemed lies. Starmer was a hero of this approach. He misled the Labour internal electorate and justified it by the values I’ve mentioned. He dropped any policy though unpopular or hard to defend in the right wing press – such as human rights for trans people, support of asylum seekers or leading a greening revolution that was distribution led.

At the moment, Twitter / X has the remnants of those two Brexit groups and both are equally offensive to what they call ‘the left’. The right-wing and nationalistic are on one side. Meanwhile, on the other side are those inclined to call anyone not willing to allow Starmer to do or say anything he wants, ‘Corbyn-cultists’.

The priorities change for a socialist without a party

I do not support a return to Corbynism and I think the constitutional changes in the Labour Party make it now a party whose main strength in my eyes is that it is preferable to naked Toryism, with its strong right-wing still in stranglehold on it. Fascism has never been nearer to us, and may come in that slow British manner but it will be very ugly – it exists now in the speeches of Nigel Farage, Suella Bravermann and others. It is unthinkable to raise the prospect of a Tory win next year but it is unclear that other parties will be mature or skilful enough to create an electoral bloc that would see as its main aim, not even the preservation of the environment of all species as urgent as this is but, the creation of an electoral system geared to greater diversity and equality to views from all parts of the political spectrum.

This, as we see in Italy and France, will not eradicate the right but it will create an open not an occulted debate. The rest follows. I think I will die ‘Forever Red’ but not, as it were. hoping this will come through pathways created by the Labour Party. The history of its logos during he period I talk about tells you a lot about hiding truths, for not all roses are red, and they do not necessarily suggest socialism.

With love xxx

Steve

I live in the U.S. and share your concern for a rising tide of fascism. I think people are scared because of all of the economic changes fueled by massive technological change and are resorting to fascism as the antidote. The fact of the matter is in my view that the train has left the station already, why would we want a fascist style dictator running it? Do people really believe this would be better than democracy. It boggles my mind that we fought two World Wars with millions upon millions of lives lost in the process to defeat fascism and now are sliding towards it ourselves! Our ancestors must be rolling in their graves!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Unfortunately you are probably correct. All love to you

LikeLiked by 1 person