What cities do you want to visit?

Jerusalem the Golden by Avram Graicer – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36291082

An earlier prompt question and my response helps me to situate myself in relation to this question. The old question was: ‘Do you have a favorite place you have visited? Where is it?’ I wrote there about how a ‘place’ differs from a ‘space’, the earlier blog (about ‘places) can be read at this link.’ I tried to summarise at the end why somewhere you visit or even want to visit remains a ‘space’ not a ‘place’, filled, or yet to fill, with impressions but most often characterised by impressions already from a scattered collection of stories and myths and selective images from various media. Here is what I said at the end, edited to clarify what I mean by outside and inside in relation to a ‘place’:

Places are not open to visitors or tourists, for the place cannot be contextualised in psychosocial interactions that combine what we see or even sense in other ways (like smells and sounds) outside ourselves and the associations we build up inside ourselves to these impressions from contact with the people that inhabit that space and make us part of them and its life. We are never really placed on holiday except in a dream of ‘places’ as the tourist superficially creates them from expectations, contingencies of a short-term sensations of it and selective and sometimes limited memories. I remember then spaces, like the harbour at Chania or the Summer Palace at the then Leningrad, with its gold statutes encased in wooden ‘coffins’ to protect them from Arctic cold and wet, the vision in match-light struck by a local guide in a-usually-unvisited Byzantine Chapel on the Peloponnese where parts of a fresco in wondrous colour flitted across my eyes, the sparrows living on our window sill in a small hotel next to the ancient Byzantine City of Mystra, on the way to the modern city of Sparta. I can enjoy all those commemorative impressions.

https://livesteven.com/2023/12/05/that-was-a-place-if-i-was-a-good-enough-writer-or-painter-i-could-recreate-it-in-ways-in-which-its-placeness-found-itself-in-a-much-larger-context-but-i-am-not-an-artist/

If this is true of ‘places’, then how much more so is it true of cities, whose meanings are compounded of so much history and legend (or more accurately so much of so many conflicting histories,stories, myths …. and other narratives as I will try to suggest about my prime example, Jerusalem). C.P. Cavafy had wise words to say about this in answer to someone he imagines saying to him, in this translation at least: “You said: “I’ll go to another country, go to another shore, / find another city better than this one. …”. This is a few of them – they could not be more biting about the fact that places are those that inhabit you rather you inhabiting them:

This city will always pursue you.

You’ll walk the same streets, grow old

in the same neighborhoods, turn gray in these same houses.

You’ll always end up in this city. Don’t hope for things elsewhere:

there’s no ship for you, there’s no road.

Now that you’ve wasted your life here, in this small corner,

you’ve destroyed it everywhere in the world.

‘The City’ BY C. P. Cavafy translated by Edmund Keeley at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/51295/the-city-56d22eef2f768 There is the Greek text below in an Appendix.

This rather unforgiving poem makes its point. Waste the city you inhabit and no other will offer redemption or that ‘new beginning’ people look for so often, and like Cavafy fail to find except in those capable of imposing powerful ‘positive’ impressions on themselves and others. So I can start a list with cities I have visited and want to see again: at the top of which is Ruined Mystra, polyglot Athens (not Paris strangely) and add to them cities I dream of seeing like Rome, Istanbul (for Constantinople primarily), Alexandria (for Cavafy) and Madrid. New York does not enter my dreams at all – but that problem is a deficiency in me. But the city that ought to be there, I almost refrain from saying for it has so often been the type of an ancient city whose cultural introjection and rebuilding it (if only in its magical names) has been found and re-found by other cultures as the consequence really of powerful stories, Jerusalem.

“and rebuilding it (if only in its magical names) has been found and re-found by other cultures as the consequence really of powerful stories”. Sion Street, Radcliffe and one of the many Sion Methodist Chapels (Sion being Jerusalem of course).

In fact, my interest in this city has been re-sparked by recently buying a beautiful book (as a remainder in England, it is now out of print in the USA) with a beautiful message edited by Barbara Drake Boehm and Melanie Holcomb for The Metropolitan Museum of Art at New York (and here New York gets added to the city wish list again) Jerusalem (1000 – 1400): Every People under Heaven, because it is a book of both many and yet few others that give account of the city. I say like few others because amongst a medley of voices, some of them angry – and sometimes rightly so – about who ‘owns’ Jerusalem, this quiet book investigates a time and space of relative peaceful co-existence and some mergence.

This, despite the fact that the editors of the book record meeting in Jerusalem the Patriarch of the Greek Orthodox Church, who there quizzed them in quite direct terms, saying: “Whose story do you intend to tell?”(1) The editors answer as best they can that they try to tell it as recorded by voices of medieval predecessors, showing conflict but also unearthing, not consensus of course, but collaboration (at least at some points and, of course, across time-space in which the pain of violence has eased). Some obvious link points are found in the transition between hospitality traditions and the advent of medicine, with a hospital ‘in Frankish Jerusalem’ admitting ‘not only Christians but Jews and Muslims as well’ and even varying diet for that purpose on religious grounds. And this was the case with scholarship and learning too that demanded even theological scholars proficient in a wide range of languages and sharing some commentary, as in the case of Maimonides and with some Christians using the Qur’an with an idea of learning from it. Moreover, books ‘written in, brought to, or sent from the Holy City’ exhibited ‘ an astonishing diversity of language and style’ based on such cross-fertilisation, between writers and teachers of writings, even of holy texts.

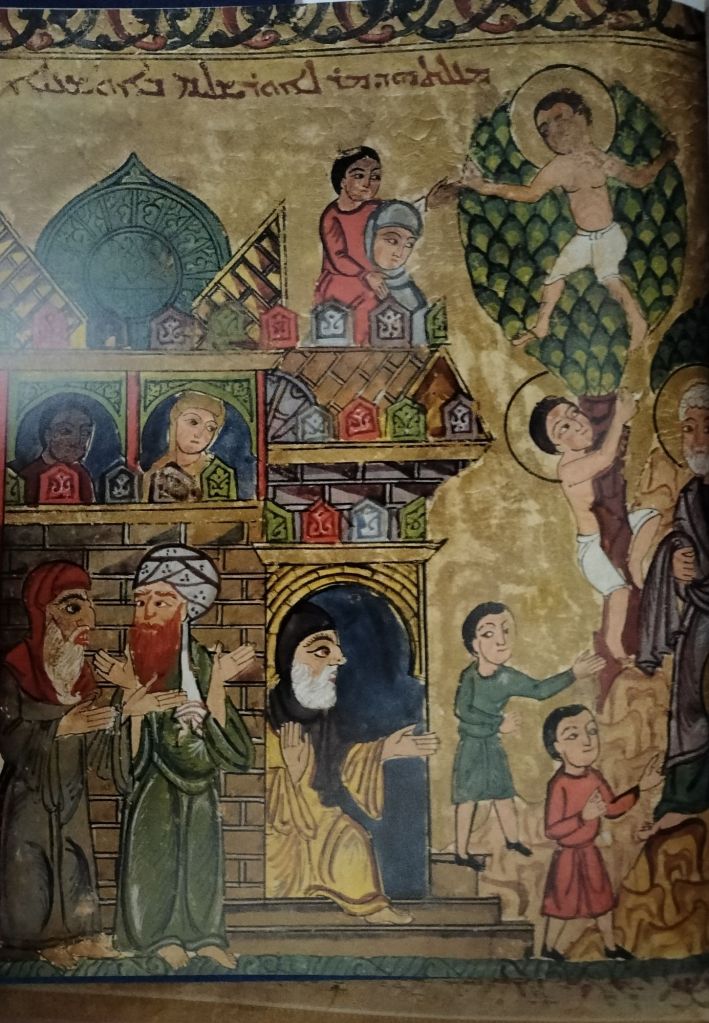

Detail of Syrian Lectionary, Barbara Drake Boehm and Melanie Holcomb (eds.) [2016:64] Jerusalem (1000 – 1400): Every People under Heaven, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art at New York and Yale University Press with the editors’ commentary on facing page

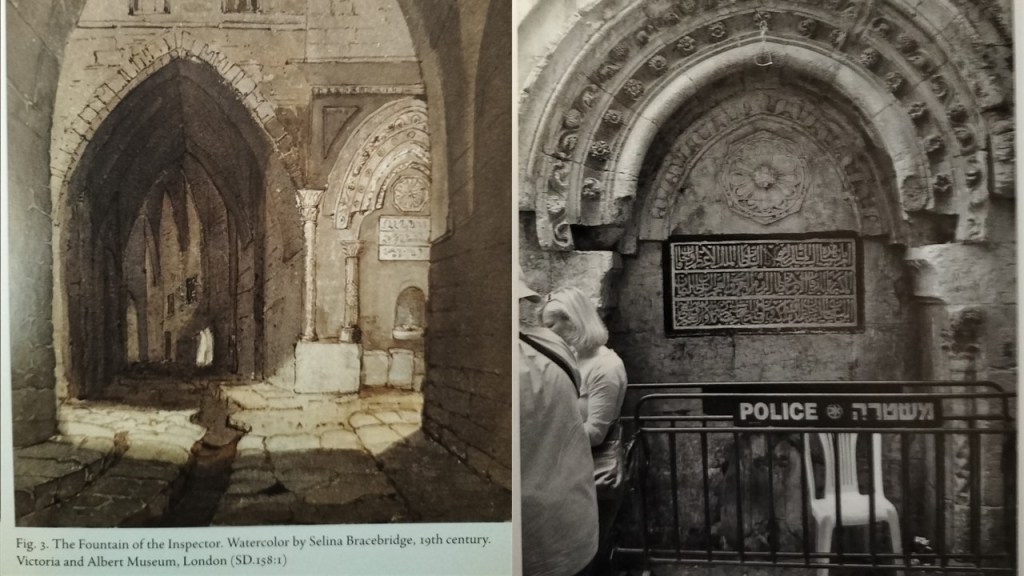

Though often thought to be a time of extreme conflict between the peoples who lay claim to know Jerusalem best, during which Crusade and Jihad are supposed as commonplace reasons for people to exert violence against other peoples, the book finds greater evidence of multicultural and multiracial reality, where mergence of cultures in its languages, texts and public architecture (notably the Fountain of the Inspector, about which it writes beautifully regarding its mixed architectural heritage. But that mergence often tolerated easy slippage between religious affiliations too, with evidence of ‘fluid religious identity’ amongst not only the laity but also some clergy and liturgies, at least between opposed sects like the Orthodox and Western Church. In one case, the mystic Ibn al-Arabi 1165–1240, says pithily that faith can be enjoyed across religious sites : “A cloister for a monk, a fane for idols, the tables of the Torah, the Qur’an. Love is the faith I hold’. Contemporary art (such as the illuminations in the Syrian Lectionary joyed in diversity: joyed in the depiction of multi-cultural and multi-faith and even cross-gender witness of Love. (2)

And this was not unusual in the Middle Ages. The Ancient Church Haghia Sophia of Trebizond, at its height of fame in the thirteenth-century, on the Northern coast of the Black Sea has as much in it to appeal to Islamic artistic traditions according to Tamara Talbot Rice, who attributes this in part to the use of ‘Seljukid craftsmen’.(3) Nevertheless, division is a fact. Indeed, quite extreme divisions exist within Christian, Jewish and Islamic groupings in Jerusalem and elsewhere, as well as there being, no doubt, a more silenced margin of non-believers or agnostics from each tradition. Each grouping can have a different story and a different claim to make of the great City but each contributes. The book has a splendid section on ‘Pluralism in the Holy City’ that explores all this with expert descriptions of the Saint Sabas Christian Monks of the Holy Land and The Karaites (a branch of Judaism but itself subject to multiple forms but who had severe tensions with Rabbinic traditions, such as those of Maimonides (whose work on re-describing the ancient Temple destroyed by Roman might is also represented in the book). Here to is a brilliant coverage of writings called in Arabic Fada’il al-Quds (the Merits of Jerusalem) which trace the sacred associations of the City for Muslims and its beautiful art. Moreover, that latter text based its belief in the sanctity of Jerusalem to Islam on a ‘biblical heritage that made Jerusalem sacred to Jews and Christians’, whilst not challenging those traditions.(4)

This book, and the exhibition it catalogues, speaks then more about the city than about monuments of violence and enforced loss. For instance there is a beautiful essay on ‘Sharing the Church of the Holy Sepulchre During the Crusader Period’ by Jaroslav Folda which argues for evidence of a ‘multicultural center (sic.)’, though, of course with specific exclusion of Jews by some Christian authorities:

Remarkably, even during times of hostility and conflict, visitors of diverse faiths still visited Jerusalem. By 1100 both Jews and Muslims returned to the Holy City, but the Crusaders did not allow them to live there, save for a small Jewish community near the citadel. … it was not until Saladin conquered the city in 1187 that Jewish immigrants were welcomed, as the Spanish-Jewish poet Judah al-Harizi recorded of an 1189 – 90 declaration: ‘…”Speak ye to the heart of Jerusalem, let anybody who wants from the seed of Ephraim come to her.”‘ (5)

Of course Jerusalem is always a cultural image of exile, loss longing to return or to re-found, and sometimes refounded. This is necessarily true of Jews of course, but it is a structure of feeling imagined as a city that is sometimes found in other outwardly alien spaces: such as the rebuild imagined by William Blake among the ‘Dark Satanic Mills’ and ‘England’s green and pleasant land’). Blake himself could not have imagined however how his poem would become a song of violent bloody and senseless war for the British Imperial commanders of the First World War, and Jerusalem become a city of military militancy in another land, as James Carroll notes in a fascinating essay in this book:

That the 1914 fevers of the Great War, despite its apparent secularity, drew on overheated religious currents running beneath the surface of power politics is suggested by the defining British war anthem, “Jerusalem”. That early nineteenth-century lyric by William Blake was set to music only in 1916, as the epoch-shattering Battle of the Somme raged: … .[6]

However, Carroll and the editors of this book made me realise that cities are often difficult to disengage from mental images that compete sometimes in the same interior subjective space where human psyches store them. They can associate with feelings and imagery of exclusion, longing, needing, coveting, and obsession: the editors tell us in an early essay that the British Journal of Psychiatry in 2000 reported twelve hundred cases in international tourists of, as named in the admitting hospital as “severe, Jerusalem-generated mental problems”.(7) There is no record that any of those syndromes experienced by real people under unreal names (aka diagnoses) were beneficent or malign in effect. What happened to the persons apparently was the acting out of what they thought of the dramas of its various holy places. And these places are multiple, for though the book records the stories under those broad cultural-religious headings of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, it never forgets how divided groupings of persons are under each of those headings and how important that is, internally to each and between each.

At some point however, amidst the violent claims of rights of ownership that ignore every other piece of evidence, easily found on YouTube for instance – such as ‘Who Owns Jerusalem’ below (It’s a piece of selective and rather insulting anti-Muslim propaganda (with some ‘blasphemous’ graphics for those who are believers), which subjects Islamic myth to the kind of analysis and biased history that both Jewish and Christian myth can be likewise queried, and available at the link if the film does not play below).

‘The stories need not be told the way they are in this film and they did not need to parody Islamic legend, though it certainly illustrates the exclusion felt variously over history by all communities. And we get some sense of how to do this historiography (and art historiography) in this brilliant book, though it never asks us explicitly to apply its lessons to modernity. I have given examples above already but the editors take care to tell us of the joy with which Rabbinical Jews like Rabbi Jacob praised the beauty built by ‘the Ishmaelite Kings; describing ‘a very beautiful building for a house of prayer and erected on the top a very fine cupola’.(8) These are not the words of a hater, neither are others used in the same essay.

Let’s take one example of the sacred art examined in that section that might also take us back to our opening theme in Cavafy. It is a short article by Melanie Holcomb full of brilliant readings of the reception of a sacred architectural feature named therein: The Closed Gate. I refer to this in my over subjective (here I go again) blog title of course. Its names are more nearly, as named in the text ‘Jerusalem’s double-arched Golden Gate, also known as the Beautiful Gate or the Gates of Mercy and Repentance, an entrance known for being intriguingly, reliably closed’.(9)

If Cavafy is haunted by one city which he failed, or it failed him – who knows – many people are haunted by the thought of the exclusion that may or may not be intended by this CLOSED gate. It cuts off The Mount of Olives from the Temple Mount (Haram al-Sharif), whose very names suggest a barrier closed to progression of holy assumption. In medieval accounts, it is still closed but, Holcomb tells us, by doors covered with bronze or iron. It is attributed as a work of Kind David to please his father Solomon and in Jewish ancient ritual it allowed passage of a sacrificial ‘red heifer’ through it. Christians associated to events in Jesus’ life-story. But its sacred nature related to the symbolic function of the gate as a portal to other worlds, and almost certainly too those between the external and internal which religions attempt to mediate or form thresholds and portals between. In accounts pilgrims found it closed and this rarity of access was linked to its moral and spiritual function. One story told of the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius (c. 1128 – 1190) approaching it in grandeur but being refused admittance by virtue of the portal’s prescience until he entered with humility in his dress and processional grandeur. Other stories abound:

Medieval Jews, citing a passage from Ezekiel (44: 1-3), declared it had not opened since before the days of exile. Nor could it be opened: …. Niccolo of Poggiboni was certain that the gate was sealed permanently after jesus’ fateful entry through it on a donkey. The scholar Muir al-Din attributed its closing to caliph ‘Abd al-Malik … to protect the Haram al-Sharif from an unspecified heretic enemy.

…, predictions of its opening invoked the end of an age. for Jews, the gate would only become unsealed at the moment f redemption. … Saladin himself affirmed the significance of the gate at the End of Time: those passing through would gain the right to paradise. the Qu’ran put it more starkly: inside is mercy, outside is torment. Though Mujir al-Din asserted that the Christians had told it would not be reopened until the descent of the Lord Jesus no surviving Christian account makes such a claim.

Whether Christians participated in this apocalyptic imagining or not, the gate is clearly correspondent to other seals that give access to bliss or torment at Armageddon. The monk Felix Fabri attests to Christians taking nails or wood from the gate (this was often done by biting a piece off whilst apparently kissing the relic) to seek grace and / or relief from disease. The gate therefore had to be guarded.(10) For my purposes this multi-faith belief in a portal to religious grace or magic, is a a good symbol of how the gate symbolised the emergence of sacred placeness in Jerusalem (inside that gate) as opposed to a non-sacred spaces outside it. As with Cavafy, it is a kind of symbol that of finding oneself at one with the eternal city of your origin, at the cost otherwise of wasting your life: ‘Don’t hope for things elsewhere: /there’s no ship for you, there’s no road’. And for those of us who have never seen Jerusalem, it feels requisite that, in these dark days for Palestine we revisit its promise in looking for resolutions of conflict that promises something to Jews, Muslims and others which is not VICTORY for either side_ a two state solution may start with resolution of Jerusalem, that divided city.

Israeli Settlements and Palestinian Neighborhoods in East Jerusalem | IMEU (Institute for Middle East Understanding).

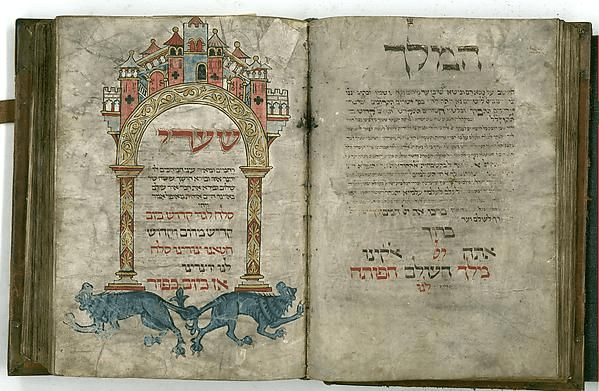

In this story nothing could be more useful a text than the Hebrew Worms Mahzor (ca. 1280) that was shown in this exhibition and gave commentary and image to The Gates of Mercy referred to above and item 58 in the catalogue. The unsealing of the gate is made analogous to the unsealing of eyes by their enlightenment and is performed by the unlocking of the tails of the fierce blue lions, symbolising its closure and lack of access, or even egress of heavenly aid to human beings. Colossal understanding is required for a nation in fear of again finding the isolation European Jews found in the darkness of the Holocaust and unable yet to confront the lack of sense in occupation and repressive separation and oppression in the West Bank and Gaza. But if religion is to mean anything, it ought to b e like this prediction from the text in West Germany referred to last: In Atonement and at-one-ment Medieval Jews felt that they would ask God to perform the functions that name him as He who “opens for us the Gates of Mercy and enlightens the eyes of those who yearn for Your pardon”. (11)

APPENDIX:

ΕίπεςΘα πάγω σ’ άλλη γή, θα πάγω σ’ άλλη θάλασσα,

Μια πόλις άλλη θα βρεθεί καλλίτερη από αυτή.

Κάθε προσπάθεια μου μια καταδίκη είναι γραφτή

κ’ είν’ η καρδιά μουσαν νεκρός—θαμένη.

Ο νους μου ως πότε μες στον μαρασμό αυτόν θα μένει.

Οπου το μάτι μου γυρίσω, όπου κι αν δω

ερείπια μαύρα της ζωής μου βλέπω εδώ,

που τόσα χρόνια πέρασα και ρήμαξα και χάλασαΚαινούριους τόπους δεν θα βρεις, δεν θάβρεις άλλες θάλασσες.

Greek text of’Η πόλις’ from: https://wordswithoutborders.org/read/article/2005-04/the-city-the-spirit-and-the-letter-on-translating-cavafy/

Η πόλις θα σε ακολουθεί. Στους δρόμους θα γυρνάς

τους ίδιους. Και στες γειτονιές τες ίδιες θα γερνάς

και μες στα ίδια σπίτια αυτά θ’ ασπρίζεις.

Πάντα στην πόλι αυτή θα φθάνεις. Για τα αλλού—μη ελπίζεις—

δεν έχει πλοίο για σε, δεν έχει οδό.

Ετσι που τη ζωή σου ρήμαξες εδώ

στην κώχη τούτη την μικρή, σ’ όλην την γή την χάλασες.

[1] Barbara Drake Boehm and Melanie Holcomb ‘Art and Jerusalem’ (2016: 4) in Barbara Drake Boehm and Melanie Holcomb (eds.) Jerusalem (1000 – 1400): Every People under Heaven, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art at New York and Yale University Press. 3 – 7.

[2] Barbara Drake Boehm and Melanie Holcomb ‘Pluralism in the Holy City’ (2016: 75, 72,71, 70, 65 respectively) in ibid: 65 – 75.

[3] Tamara Talbot Rice (1968: 55) ‘Analysis of the Decorations in the Seljukid Style’ in David Talbot Rice (ed.) The Church of Haghia Sophia at Trebizond Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press. 55 – 82.

[4] Carole Hillenbrand (2016: 84f.) ‘Merits of Jerusalem (Fada’il Al-Quds)’ in ibid: 84 – 85.

[5] Jaroslav Folda (2016: 131f.) ‘Sharing the Church of the Holy Sepulchre During the Crusader Period’ in ibid. 131 – 133.

[6] James Carroll ‘Jerusalem: The Crucible of Holy War’ (2016: 204f.) in ibid. 203 – 205.

[7] Barbara Drake Boehm and Melanie Holcomb ‘Art and Jerusalem’ (2016: 3) in ibid: 3 -7.

[8] Melanie Holcomb and Barbara Drake Boehm (2016: 128) ‘Experiencing Sacred Art in Jerusalem’ in ibid: 113 – 128,

[9] Melanie Holcomb (2016: 129) ‘The Closed Gate’ in ibid: 129 – 130.

[10] ibid: 130

[11] Item 58: The gates of Mercy (detail and illustration and explanatory text) in ibid: 140f

One thought on “If the city that promised you love has closed its gates on you, is there any other city to which you can go: My heart in longing for some Jerusalem the Golden.”