What we create from all creation comes,

No something from some nothing comes at all

And brightest lights still travelling from suns

Long after their death, engendered fall.

Though we do not see that act of making

It depends upon those many at work

To make it; source material faking

Its absence and worker’s struggle let lurk

Beneath the cover of beauty resounds

The phrase ‘from nothing, nothing comes’ and I

With labour of the dead, my work confounds

Nor to myself alone, can credit lie.

Stevie’s ‘poem’ or ‘doggerel’

King Lear is a play about fatherhood and its claims of authority over that it believes it alone creates – which in that play and for Lear are his power and authority over kingdoms and over his offspring. So much thought has sometimes been spent on the origins of those daughters Goneril, Reagan and Cordelia: not least by Gordon Bottomley who wrote a play, illustrated by the great English artist, Paul Nash, as a young man called King Lear’s Wife. The point is that the greatest tyranny that can be exerted is by those with power and the ownership of resources exert over those who really create – the forgotten and marginalised – the poor and labouring to which Lear is reduced in his madness and women, who labour in the home. Lear’s statement to Cordelia in Act 1 Scene 1, line 99: “Nothing will come of nothing. Speak again”, evokes a classical debate in theology and science. On one side the proponents of an all-powerful Patriarchal God, the God of the Judaeo-Christian tradition, who asserts the principle that God created the universe of worlds ‘out of nothing’ (Creatio ex nihilo in Latin or ‘creation out of nothing’), and a classical tradition, attributed to Parmenides, a Pre-Socratic philosopher but often associated with, because inscribed by, Aristotle, οὐδὲν ἐξ οὐδενός in Greek, Ex nihilo nihil fit in Latin (no thing is made of nothing).

Beautiful art can be made of the first idea, though the labour of its creativity may complicate its message were it visible, which it often it is not because we lose ourselves in the beauty of the object, as in this beautiful winow shared in Wikipedia on the subject of the Tree of Life (‘by Eli Content at the Joods Historisch Museum. The Tree of Life, or Etz haChayim (עץ החיים) in Hebrew, is a mystical symbol used in the Kabbalah of esoteric Judaism to describe the path to HaShem and the manner in which He created the world ex nihilo (out of nothing)’ as described by that august collaborative encyclopedia. Here is the picture:

By Michele Ahin – Joods Historisch Museum – Levensboom glas in lood – Eli Content (Midden), CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8292664

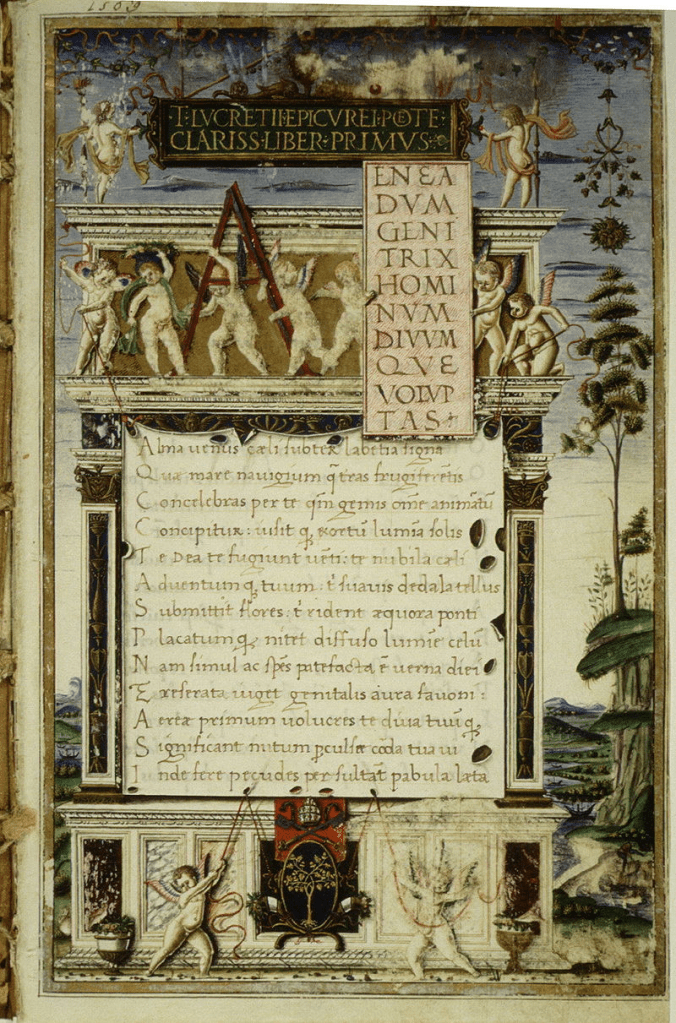

But the opposition in that debate is also represented in the art of creative writing, famously by Lucretius, and this form of words in English seems to suggest that Shakespeare knew this argument when thinking of King Lear.

Beholding many things take place in heaven overhead

Lucretius ‘On the Nature of Things’. (Written 50 B.C.E) Translated by William Ellery Leonard

Or here on earth whose causes they can’t fathom, they assign

The explanation for these happenings to powers divine.

Nothing can be made from nothing—once we see that’s so,

Already we are on the way to what we want to know.

Lear takes the idea of partiarchal creation very far. In the first scene of his extreme madness he enters the stage in a storm, he is willing to have all who see and hear him believe he has created out of the ‘nothing’ of his tortured mind:

Blow winds, and crack your cheeks! Rage, blow!

King Lear, Act III, Scene 2, lines 1ff.

You cataracts and hurricanoes, spout

Till you have drenched our steeples, ⟨drowned⟩ the

cocks.

You sulph’rous and thought-executing fires,

Vaunt-couriers of oak-cleaving thunderbolts,

Singe my white head. And thou, all-shaking

thunder,

Strike flat the thick rotundity o’ th’ world.

Crack nature’s molds, all germens spill at once

That makes ingrateful man.

This speech is amazing. Lear is not only passing himself off as the God of creation and destruction but attributing that act to a divine fatherhood – the world is pregnant but at risk of violence nevertheless (its ‘rotundity’ is being flattened violently, as women might have grown to expect of their hubristic patriarchs) and creation attributed entirely to male sperm (the ‘germens’ that must spill) that are the only authors of ‘ingrateful man’ out of nothing. As Lear’s madness compounds and in this sorry state the Fool will teach Lear that the true ‘Nothing’ in this play is he, and that the truly creative are those that worked at it – by good or, as in the case of Goneril and Regan, willing evil:

FOOL: …I had rather be any kind o’ thing than a Fool. And yet I would not be

My italics: ‘King Lear’ Act I, Scene 4, 189ff.

thee, nuncle. Thou hast pared thy wit o’ both sides and left nothing i’ th’ middle. Here comes one o’ the parings.

The point about Lear is that Lear must learn that his early curse on Cordelia has really resonance. Everything that is made or created is made out of the blood and sweat of the marginalised and forgotten (the poor never seen in Lear’s court like the man gathering ‘samphire’ on the cliffs of Dover that Gloucester – being blind – does not see), even those dead upon which the living tread unthinkingly.

My little poem – hardly creative, is a nothing, but it is, as it says or tries to, made out of something, the loving inheritance of forgotten pasts and dead women who laboured and struggled – the forgotten people never thought of as creative. It’s a belief common to socialists.

With all my love

Steven