I was born 24th October 1954 in Halifax General Hospital at Salterhebble, Halifax.

As I chose this question, you would think I had thought deeply about the year of my birth, but that isn’t in fact the case. Finding significance in such things anyway seems to me a kind of extension of pattern-finding and such pattern-finding is surely an imposition of pattern onto history, of which set of events it does not disclose any significance or truth. Perhaps we all desire to find significance, truth, or even magic, in the entirely contingent facts that describe or narrate one’s self. But, in the end, 1954 is just a number (one thousand, nine hundred and fifty-four); a count of the years since year 0 AD supposedly. But even 1 AD is a kind of fiction qualitatively, or a mythical element of a questioned fact, for this is supposed to be the year count AD (Anno Domini – after the Lord Christ).

Such counts are a matter of dispute even by those who find magic or spiritual significance in the supposed facts of Christ’s life, which have long been disputed. It is a matter similar to, and cognate with, the spiritualisation of a number of timed units that makes December 25th the supposed time of recurrence of the original birth of Christ too. For that ‘date’ is a thing extremely doubtful in relation to a man in history and certainly not factual, being a date established by tradition and the authority of a very human institution nevertheless, a Church.

Christian churches in fact have always tried to quantify qualitative events of Christ’s life, like the holy or virgin birth of its spiritual icon. It became a matter of dispute between the early churches that took on the mantle of the Roman heritage to claim their imperial significance, a debate between the truth embodied in a schedule of numbers bearing still the marks of the old ‘pagan’ worship of the Sun in ancient Rome: the dispute, that is, between the Julian or the Gregorian calendar. Here is the Wikipedia account:

The Julian calendar is a solar calendar of 365 days in every year with an additional leap day every fourth year (without exception). The Julian calendar is still used in parts of the Eastern Orthodox Church and in parts of Oriental Orthodoxy as well as by the Amazigh people (also known as the Berbers),[1] whereas the Gregorian calendar is used in most parts of the world.

This calendar, proposed by Roman consul Julius Caesar in 46 BC, was a reform of the earlier Roman calendar, a largely lunisolar one.[2] It took effect on 1 January 45 BC, by edict. It was designed with the aid of Greek mathematicians and astronomers such as Sosigenes of Alexandria.[3]

The calendar became the predominant calendar in the Roman Empire and subsequently most of the Western world for more than 1,600 years until 1582, when Pope Gregory XIII promulgated a minor modification to reduce the average length of the year from 365.25 days to 365.2425 days and thus corrected the Julian calendar’s drift against the solar year. Worldwide adoption of this revised calendar, which became known as the Gregorian calendar, took place over the subsequent centuries, first in Catholic countries and subsequently in Protestant countries of the Western Christian world.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julian_calendar

Many, since this example (never authorised by Christ Himself), have tried to make the numbers of their birth-date into a parallel magic if not religion, a cyclical recurrence of transcendent meaningfulness. Churches however did it with Christ to affirm their particular primacy of ownership of His truth, as in the tussle between Eastern Byzantine Orthodoxy and the upstart Popes. Christ’s birthday is imposed on non-Christian religious models, originally for foreign and imperialist churches to curry favour with folk beliefs.

Nowadays, of course, the ‘magic’, always in inverted commas and associated with the everyday like a child’s laughter, serves mainly the praise of commodities, advertising and annual boosts to economic growth but it still tries to pretend it is about ‘magic’ (and if not of the spirit, then of the ‘magic’ of familial love). We know that because advertisements tell us so.

Such modern myths are possibly the cause of those bad-tempered and oppressive family occasions (most usually oppressive of women in my memory of them) many of us remember most. Finding significance, or predictive magic, in birth numbers is the speciality of that nonsense called numerology, another hang-on from pre-Christian religions and the sacralisation of quantity in ancient religions.

‘Numerorum mysteria’ (1591), a treatise on numerology by Pietro Bongo and his most influential work in Europe

So having satisfied myself that any findings about my year of birth, 1954, have a random contingency to me, I consulted Wikipedia’s page, ‘1954 in the United Kingdom‘ (here is the link). Here are listed a selection of the contingent facts about that year from which I plucked two. Both of these in a sense came to be important to me over my life experience, if necessarily by virtue of a series of accidents. They are, not necessarily in date order. They are a significant moment in the career of Iris Murdoch as a novelist, that of her first novel, and the trial of Peter Wildeblood.

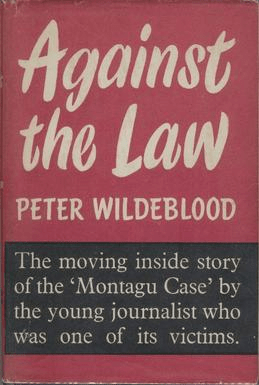

The first became important fact to me for many contingent reasons explored below. The second is a fact I only learned later as I began to find my place on the margins of queer history, for Peter Wildeblood‘s trial (or more accurately, though I balk at the aristocratic lead this betokens, the ‘Montagu’, trial) was vital in the development of queer liberation in the UK. Let’s list them as cited one by one.

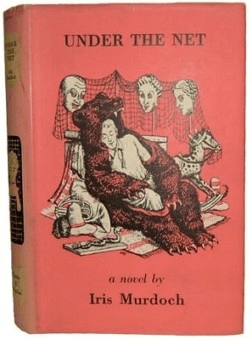

- Iris Murdoch‘s first work of fiction, the philosophical picaresque novel Under the Net.

Cover of first edition of ‘Under the Net’ by http://pictures.abebooks.com/LUCIUS/1147213609.jpg, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=19926004

- ’24 March – After an eight-day trial at Winchester Assizes, The Lord Montagu of Beaulieu, his cousin Michael Pitt-Rivers, and their friend Peter Wildeblood are convicted of “conspiracy to incite certain male persons to commit serious offences with male persons” or buggery and related charges.[4] Pitt-Rivers and Wildebood are sentenced to eighteen months and Lord Montagu to twelve months in prison’ (Wikipedia).

Cover of 1st ed. of Against the Law by http://www.abebooks.com/servlet/BookDetailsPL?bi=1360304045&searchurl=an%3Dpeter%2Bwildeblood%26bi%3D0%26bx%3Doff%26ds%3D30%26fe%3Don%26sortby%3D2%26sts%3Dt%26tn%3D%2522against%2Bthe%2Blaw%2522%26x%3D21%26y%3D10%26yrh%3D1955%26yrl%3D1955, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27784343

Both have a complicated relation to my life as it unfolded. Peter Wildeblood only later came into my ken, whilst my husband, Geoff, was researching his pre-university dissertation at Ruskin College Oxford on the criminal law against acts of queer sex and sexuality. However, I think now that I should always have revered that incident, so fundamental in its later interpretation of queer history, especially through Wildeblood himself and his submissions to the Wolfenden Report produced in 1957. Wofenden reported on – as if cognates – the legal aspects of ‘homosexuality’ and ‘prostitution’ as examples of acts labelled as ‘offences’. The late implementation of that report in 1967 in a Sexual Offences Act decriminalised homosexual acts ‘between consenting adults in private‘. Those apparently innocent words ‘in private‘ opened up a whole series of policing crackdowns on meeting places to which queer people were restricted, that included theoretically even flats in blocks of houses with a shared entrance that were not considered therefore ‘private’.

These kind of events were not to stop for many years and led to many very terrible incarcerations or enforced treatments, not unlike those surrounding the earlier chemical castration of Alan Turing in 1952 and who committed suicide, some believe though others question the evidence, in 1954 (would you believe).

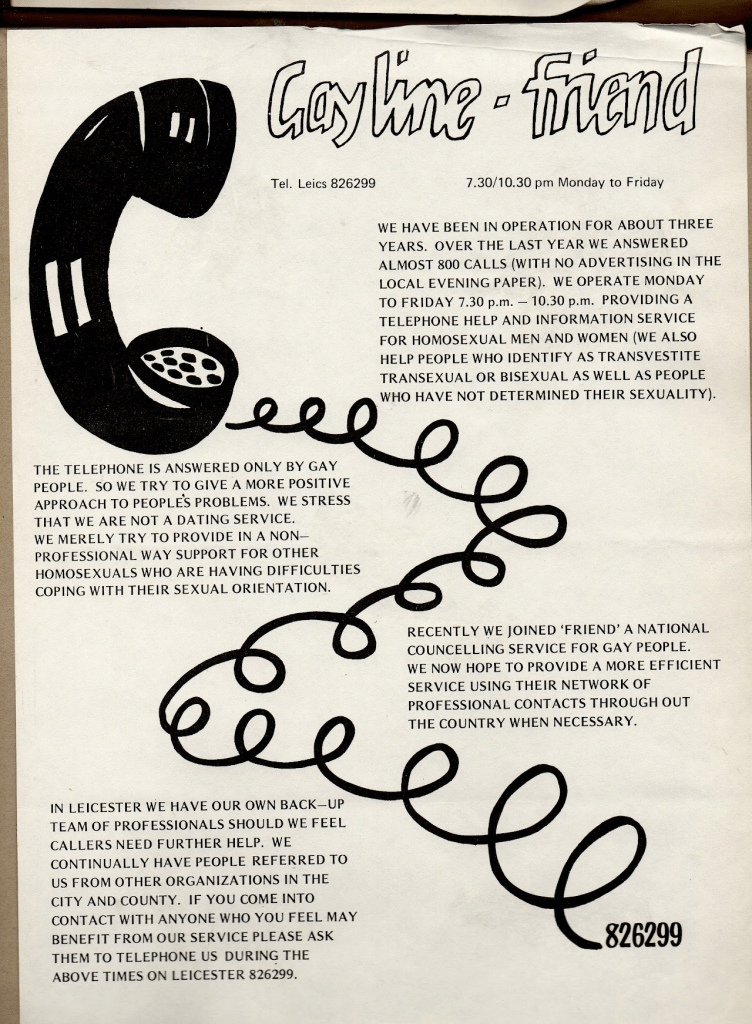

But let’s follow through links to my life of the incidents following Wildeblood’s trial. I had met and began to live with my husband in 1977 in his home in Sileby, Leicestershire. We moved to Leicester shortly afterwards (I was still supposedly studying for a Ph.D at Leicester University, to which I had decamped from Kings at Cambridge). There, we both took over the administration and, in part staffing, of Leicester Gayline, although this staffing on some nights was often just me whilst Geoff was studying in Oxford.

Just looking at the leaflet dates one in queer history, especially the faith we had in talking therapy (it was Geoff who negotiated our alliance with National Friend, a gay co-counselling agency run on a Samaritans type model). However, I am proud of the specific staffing we attained with nights for trans people who only wanted to speak to trans people for instance. Of course, our knowledge then of trans variation as you will see in the leaflet, was minimal.

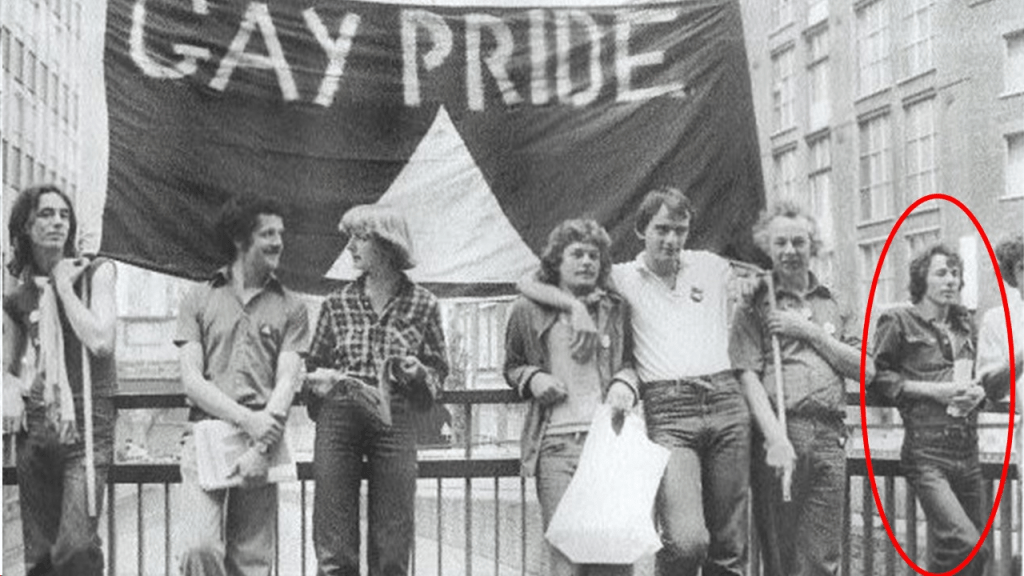

The point is I was now placed, if not specifically nameable, in queer history. My husband was however nameable in that history. Although we both engaged in public campaigns – against the Leicester Mercury which besmirched Gayline, against W. H. Smiths, who would not stock Gay News but he led them. He appeared in Gay News nonchalantly leaning against a barrier, on the protest line at the Gay News Blasphemy trial outside the Old Bailey in London.

My rather cute hubby, Geoff (ringed in red), at the Gay News Blasphemy trial (outside the Old Bailey). So many of those heroes featured less centrally in my life, such as Bill Thorneycroft, to the left of Geoff, who headed the ‘Communist Party of Great Britain’ LBTQ+ section and was, as I was to become, for a heady while, a Eurocommunist.

As for the Iris Murdoch novel, her first fiction work, this was a different story. I have a copy of the first edition now but it was a later addition than most in that library because of its then rarity (mine has a chipped dust cover). Iris Murdoch mattered to me first as a contributor to my understanding of complicated relationships between modernity and individual responsibility, for it was she, not Sartre, that committed me to a kind of individual animism. Sartre was still locked in the box called Existentialism is A Humanism that I read in the 6th form and was still unwilling to name animality (rather than HUMANITY), properly understood and not confused with violent ‘primitivism’, as at the basis of significant life. She got me nearer to my lifelong position on this question, with the help then of reading at university the modernist anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss. The latter seemed a much more important thinker then, to a position that might be called a philosophy of the mind and body, for he showed the power of binaries as a mythical structure on the formation of thought process and the perception of supposed ‘reality’.

The link to Murdoch though was in fact forged by force of the love of literature for I was taught at University College London (UCL) and, for a time marginally befriended by, the recently deceased novelist A. S. Byatt (known as Mrs Duffy as a teacher to us). Her book on Murdoch, her personal friend, broke the mould of criticism of the modern novel before the advent of postmodernism. Indeed Byatt once told me that she had mentioned me to Murdoch on a visit to her in Oxford. Murdoch, then surely in the process of dementia in which she ended her life and who often made up.jingles, apparently jingled thus, Byatt told me, “Bamlett, Hamlet, Bamlett, Hamlet …” and laughed. For a moment then, though unevidenced, other than in this reminiscence, in a public literary history, I was linked to The Black Prince.

While I was being taught the modern period in literature by Byatt, Murdoch’s The Black Prince was published and it, and of course that with the beautiful novel The Bell,that first showed me that being queer was fundamentally affirmative of my sexuality and its orientations and not otherwise. Murdoch indirectly related queerness to an understanding of the diversity necessary to understand what an ethical theory of life, and a modern philosophy of morality such as Murdoch was building in books like The Sovereignty of Good, might be. She saw it as like any other newly modern theoretical openness about an old phenomenon that varied continually across history such as same-sex love.

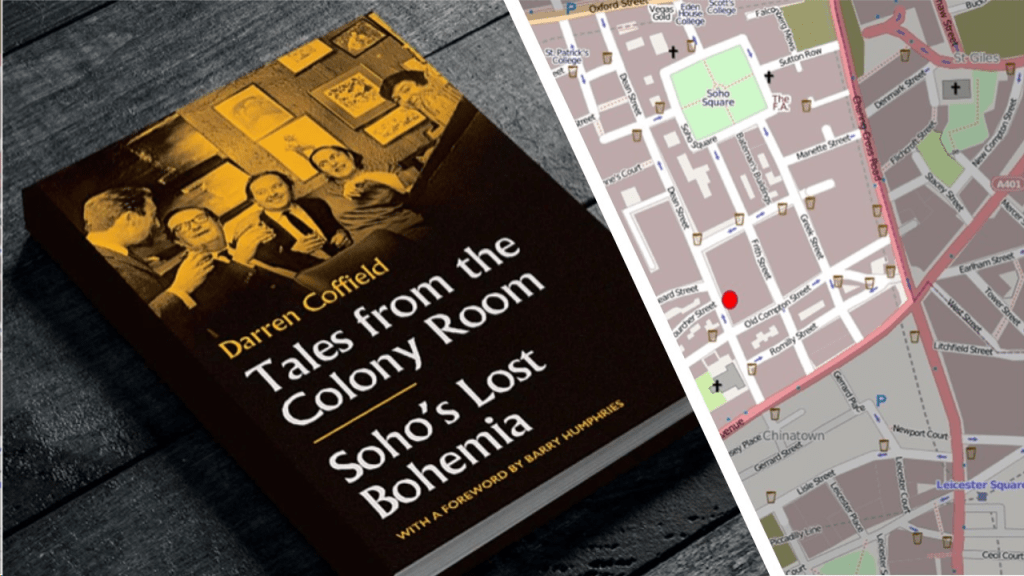

Here was a novelist who showed that love crossed boundaries set by narrow and conventional thinking and a world which was passing as it seemed through this literary evidence: at least among the rebellious amongst our thinking and typing class. She showed how it happened and why it mattered. And Under The Net was full of in-jokes too for those who, like Murdoch, knew the after-hours bars like the Colony Room and the whole queer world of Soho ruled by the likes of Muriel Belcher and Francis Bacon (see my blog on this at this link). For instance Iris says, presumably promoting her male narrator’s rather flexible, if mainly heterosexual, sexual attitudes:

By now it was about opening time. It seemed useless to start ringing up the night clubs at this hour, so there was nothing to be done but work Soho. There is always someone in Soho who knows what one wants to discover; it’s just a matter of finding him

Iris Murdoch ‘Under the Net‘ (1954): 36

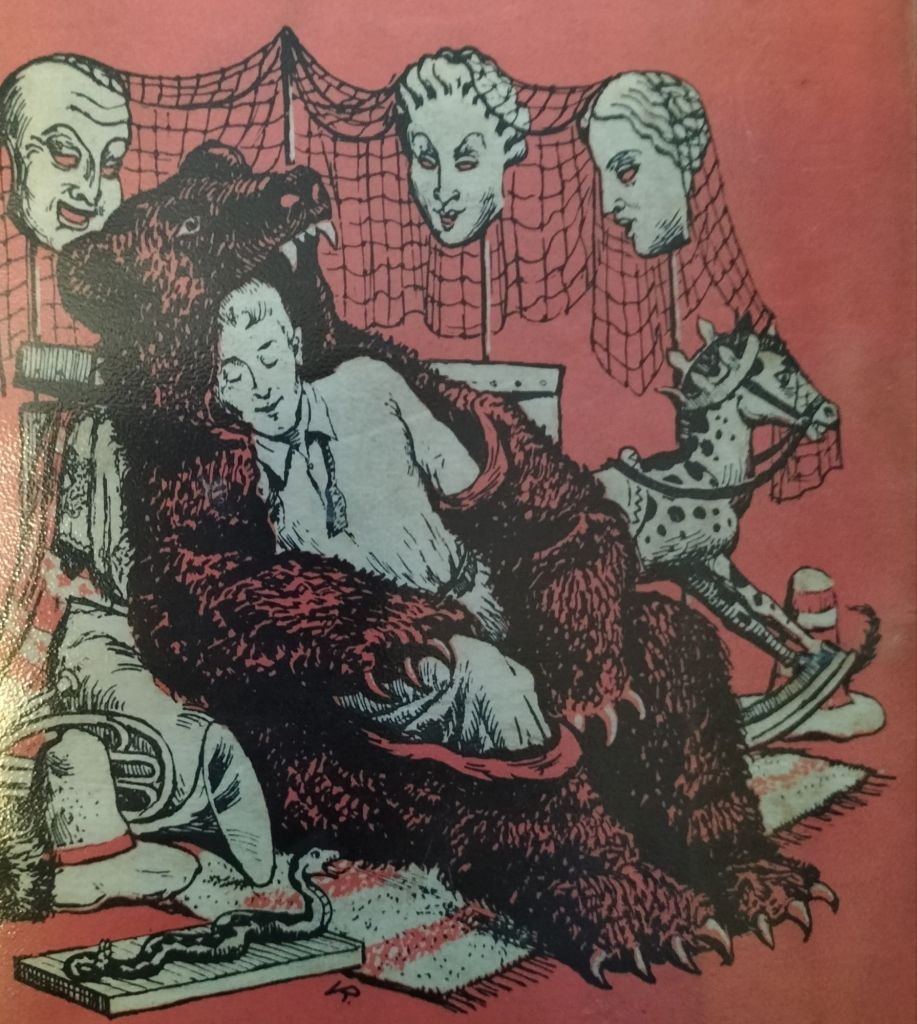

But even the wonderful cover illustration by Victor Ross of the 1954 Under the Net was a cartoon of omen I think as I look back at it, or more truly take it down from my Murdoch shelves and read its cover picture on the dust jacket. The net, which was once used in hunting large animals, as displayed by Ross is here, appropriately perhaps as it were, almost but not quite thrown over the bearskin under which the hero hides (its clawed paw fondling his knee). But that net is also clearly a web, a common metaphor in Murdoch, that binds him into a multiplicity of references to the enactment or performance of human/animal emotions and to childhood; including Greek tragic theatrical masks, a symbol of ancient wisdom, the serpent – to his left – and symbols of childhood narcissism – the wish to be a king in the the crowned rocking-horse and the horn instrument – and art.

Victor Ross cover illustration from my copy of the book

There is a picture then here of much of what is iconic in my thought still as an adult whose first airing was in this novel, taking into account of course though, as I said at the blog linked here, that I balk at that term adult too, as yet another imprisoning culturally symbolic binary as Levi-Strauss should have taught me already.

But whatever evidence there is of design here is, of course, neither magical nor predictive at the time – it is a pattern such as older people, as I am now at 69, are constantly finding in their lives. It is not only elders though, because as a trait in thinking it seems central to adult narcissism. It is a product of reflexive reflection – a distortion of thought that sees pattern in random marks, words or images, which psychiatry names Pareidolia. Psychiatry moreover sees that latter label as a subset symptom of apophenia, itself a subset of the psychosis once labelled schizophrenia. On my own part, I believe this phenomenon to be basic to our normative psychology and often unrecognised in its effects of creating the illusion of magic or mysterious correspondence.

De Quincey (or was it Coleridge?) says somewhere – somewhere I can no longer find but I think it is in Suspiria de Profundis – that, if we have a mirror before us scratched by many random markings and cuts, the introduction of a candle in front of that mirror will show a deepening series of concentric circles around the reflection of the flame. But this pattern is not truly there. It is created as a perceptual illusion by the centering focal point of an introduced light. I believe that is that the philosophical Romantics saw the mind as like that flame and I think they were right. Romantic thinkers might carry such a phenomena through to proofs of religion, such as those found in Platonism, OR into some theory of the Kantian transcendent. It is perhaps the nearest we get seeing through ‘a glass darkly’ to being ‘face to face’, as that stunning material for the Neoplatonists, St. Paul puts it.

Personally, I would not take that latter step and I have no doubt that I am not savvy enough philosophically to make that even matter, though I would also not confuse those perceived patterns that I experience cognitively and affectively with illusion, delusion or a psychiatric symptom. I think such phenomena reveal part of what makes human consciousness akin to a means of achieving knowledge without being overwhelmed by its random multiplicity. It is possible we will never do without it, though we recognise the implausibility of some of its findings – those that pretend a real and/or physically embodied relationship to the noumenal, through the pineal gland, as with Descartes most ridiculous assumption or the analogy of the incarnation generally.

So, that’s IT, my 1954.

With love

Steven xxx

One thought on “Is my birth year (1954) significant?”