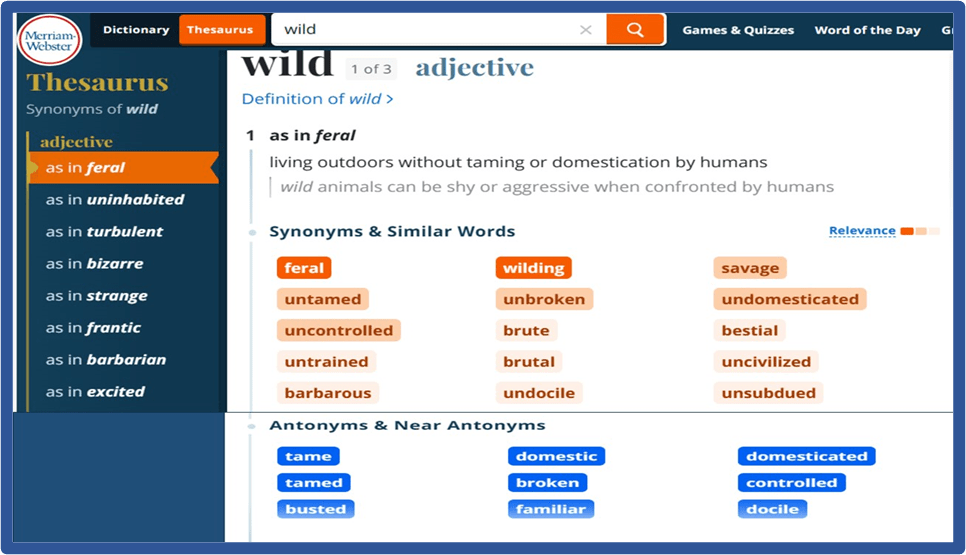

Definitions aren’t always necessary but here I think they are, for the idea of the ‘wild’ has always has problematic associations because it only has meaning in contrast with its antonyms (words with an opposite meaning) and hence is easily absorbed into binary thinking. That is more obvious in contexts set by specialist synonyms of its supposed meaning, such as ‘unbroken’ below, usually used of a horse purchased for human use but as yet not subjected to the controls necessary for that use that allow us to descried the horse as broken. You can’t forget that in other uses of the word, such as for instance in talking about fine pottery. Pottery that is unbroken would have positive meaning, so much so that it is a term we would rarely use for a ‘broken pot’ for that is so negative it queries whether the pot named actually has any present existence. You can’t help however feeling that there s something sad about the idea of a ‘broken horse’ which suggests something not only controlled for the use for purposes alien to its ‘nature’ (a problematic concept nevertheless) but as somehow destroyed, as a thing that hast some notion of what it means to be a ‘horse’.

The idea of a ‘wild horse’ is a difficult one. It so much invokes notions of something negative because it has not been, and cannot be expected to be in any duration of the future, controlled in any way that meets the needs and expectations set by human desires alone. And these desires are aligned with the human desire to see something wild, by which is usually meant something that is not overtly controlled but set within bounds and other kinds of control that minimise the danger we see potentially to our human desires, even of physical survival. Such wildness that appears antagonistic to the human is always demonised and the danger always exaggerated, as if the damage the animal poses to human hubris and pride in species dominance were always a form of struggle for physical survival, of being the one that eats the animal and is not eaten by it.

The funniest use of this in art has a very serious point to make. In Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, the character Antigonus meets his fate, possibly as poetic justice for his service to the tyrant Leontes, as he takes the child Perdita, suspected of illegitimacy by Leontes her father, to be abandoned in ‘Bohemia’ (a jazzy pastoral version of the idyll of country life haunted by a few ‘wildnesses’). One such wildness imagined is a bear. Leaving the child to her fate, Antigonus is said in the stage directions to ‘Exit, pursued by a bear’. A blog by the contemporary Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre puts this stage direction into context. Though bear costumes are known to exist and that it was likely the bear was enacted by a human male, the bear was there to represent the ‘wild animal’ lower classes audiences delighted to see, and with which they were familiar. They were familiar because top of the pops in entertainment and easily available on the South Bank of the Thames was bear-baiting, where captured bears kept normally in kennels were tied to posts to be torn to pieces in an unequal fight with packs of dogs. The delight in seeing ‘wild animals’ I would argue has always been a version of seeing the wild WILDLY controlled.

The Royal Shakespeare made a sophisticated joke about this in their 2009 production, which I can only wish I had seen, of making he bear out of torn pages of the very symbol of the refined and cultivate – a book – and animating the wild freeness of this huge paper animal. Nevertheless, paper is flimsy. We still, I think have the upper hand.

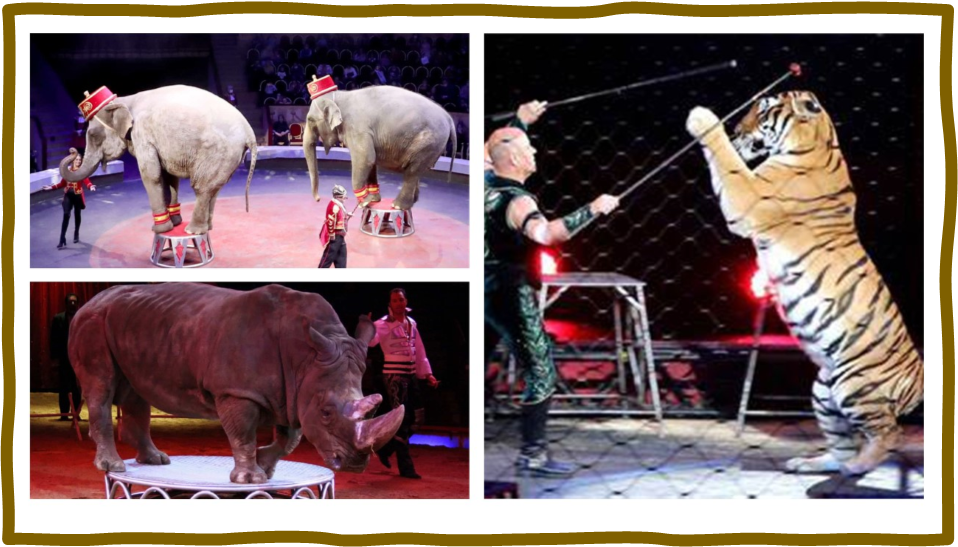

And though circuses with ‘wild animals’ (actually highly over-controlled and restricted ones) are now banned, they were often justified as first, a chance to allow children to see ‘wild animals’ they had never seen close to and to preserve species threatened by human greed for constant economic growth at whatever cost to natural resources. You can tell when nature is a resource, we soon let it be a ‘waste’ product when used to its limit – when to care for it costs more than its return to us in profit or pleasure. In circuses, what amused is the ‘wild’ made to look domesticated and controlled in the most humiliating of ways for the animal (and animals do, before you say it, have the capacity for such cognition as a matter of both observation and research). A picture might tell us more.

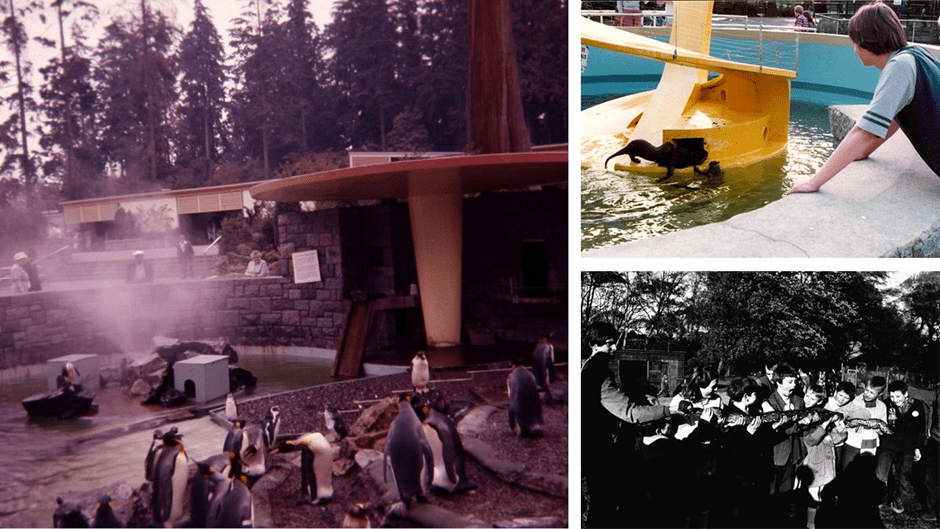

And zoos are not far behind in this litany of shame, however better regulated now that hitherto, where private finance could and did set up a zoo by private finance employing people with no normal of animal needs in Stanley County Durham (near where I live where I met an ex-keeper with tails of how ‘wilder’ animals were shot and buried in the Park secretly) for the benefit of mining families – as if the degradation of miners’ lives into captive acquiescence underground were not enough.

People enjoy CONTAINED wildness, whether the containment be an an equal cruelty as in fox hunting or bair-or-badger-baiting, or an a fence or wall to preserve one from the effects of what you think is ‘wildness’ but is actually an attempt to resist control that degrades and often harms – as for thise penguins overcrowded in Stanley.

Walking around home I see llamas and alpacas farmed as frequently now as sheep and cattle. Horses bought for someone’s 3-year-old ‘princess’ abandoned to lack of care and neglect in fields without secure water, food or supply of shelter from heat or cold. Of course, they aren’t wild. But the distinction is a fine one. Seals often swim around the North East coast, some up the Tees as far as the Tees Flood Barrage and ‘Wild Waters’ park. As they navigate the polution, I sens a containment apparent that mitigates ‘wildness’ and makes it subject to our not their needs even if only by omission of care for the needs of others. I see herons often, but less often year by year. So ofen ‘wild’ to us means ‘brutal’ as in the synonyms above and we use that to justify control of animals as they might have lived but it also means ‘excitement’. Even Emily Dickinson called for ‘Wild Nights’, and a ‘rumpus’ is a good child equivalent of finding that place ‘Where the Wild Things Are’ as Maurice Sendak (bless his closeted queer heart) knew.

In Sendak hybrid human-animals substitute for the nights of passion he dreamed of. Our need for wildness (contained of course) to see helps to flatter our need for sensational excitement without commitment to the consequences to our self-image, especially in the case of poor old Maurice Sendak. One day we will face ourselves with this question: Not only ‘why’ do I want to see contained wild animals but ‘What’ needs in me does that covering need suggest. And what threshold do we want to cross from control and self-expression, regardless of the control of our, as we think, ‘better selves’.

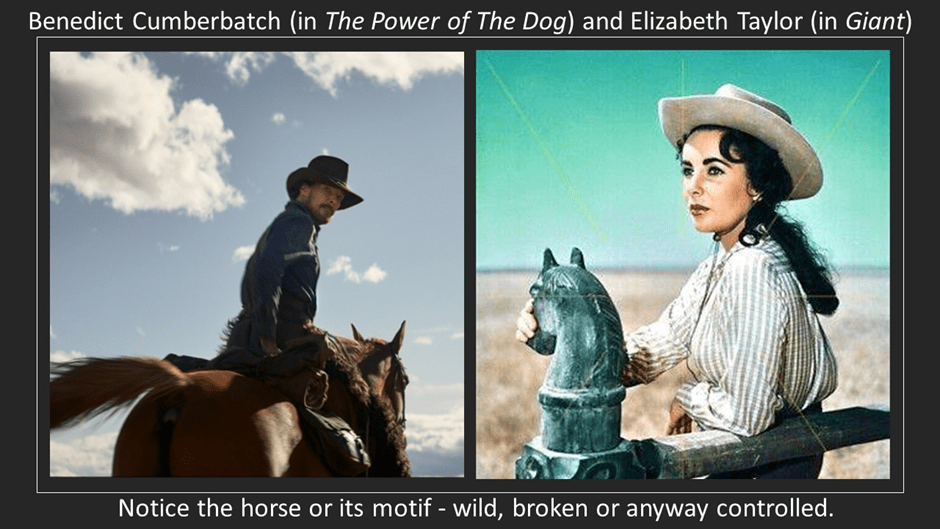

And what did Maurice like about male feet particularly? Goodbye for now. And if you wan t to see how this motif runs by regarding wild horses, broken and unbroken, try seeing again the breaking in of a horse that leads to marriage in Giant (where the horse must conveniently be shot because over-ridden by a frustrated sister of the hero who also loved that hero) or even better in that masterpiece of repressed sexuality with Benedict Cumberbatch, The Power of the Dog, and the brilliant novel that spawned it. There are links to my earlier cognate blogs on each of the titles of the films.

With love

Steve