What are your feelings about eating meat?

In the latest set of stories, The Pole, by J. M. Coetzee contains one of his favourite characters, Elizabeth Costello, who tells her son that as a committed vegetarian,as is Coetzee of course, her favoured project in her old age would be to support the building of an abattoir in the centre of her city where animal slaughter and processing of the corpses into meat could be seen happening.

‘The Times of Israel’ took this photograph of abattoir waste: a river running with blood: https://www.timesofisrael.com/stream-runs-red-with-blood-as-slaughterhouse-refuse-conjures-up-biblical-plague/

This is a kind of parable of the common statement that people who eat meat should do so in full understanding of the cruel processes involved in such mass slaughter. And knowing has to involve seeing, and otherwise fully sensing, including the smell of blood and excrement involved, the process of killing, dying, bleeding and evisceration.

Is a glass abattoir enough then? For glass still sanitises an event, places a barrier between it and the most basic of our sensations, the olfactory.

My feeling is that it is not enough. That is because the value of food involves those very basic sensations – those nearest to the driving force of the sensation of animals who predate naturally on raw flesh such as the cat genus – as means of the appreciation, both appetitive and aesthetic, of human beings who like to intellectualism eating as a ‘refined’ process. Watch any of the ‘Professional Masterchef’ programmes to see how professionalised and remote from basic life processes this word ‘refined’ becomes in the matter of both the cooking, and amalgamation and presentation of foodstuffs even if dealing with a lump of flesh near the heart of a once beautiful animal.

Coetzee earlier in his life wrote a series of parable-like story essays called The Life of Animals. The focus of one piece, called ‘The Philosophers and the Animals’ is a man, a writer of stories, who delivers a lecture saying that the problem with philosophers, and he marks out Descartes, whose view of humanity were basic in regarding Nazi death camps as an offence against humanity because they broke an expectation of sympathy all human beings have to n relation to others of the same animal genus.

The lecturer insists that sympathy must and has to extend not through some abstraction of humanity but the commonality of life between all animal species. He contends with Thomas Nagel’s question: ‘ Can I share the being of a bat?’ He argued that a novelist, like himself, can share the being of an imagined character such as Molly Bloom , from Joyce’s Ulysses, and continued by saying that IF:

… I can think my way into the existence of a being who has never existed, then I can think my way into the existence of a bat or a chimpanzee or an oyster, any being with whom I share a substrate of life.

The Lives of Animals, page 35.

Life is best represented in its most basic processes: the breath of life but also the finding, selecting, intake, processing internally and getting rid of its waste materials. These processes are so basic that many civilizations test their distance from animal life by their disgust at animal processes including, especially, excretion. In the eighteenth century, Norman O. Brown tells us in his chapter on The Excremental Vision, high cultural values could only be tested by facing basic facts like this, hence Jonathan Swift’s complex reactions to the fact of his swain Strephon discovering that his loved one, Celia, shits.

So things, which must not be expressed,

When plumped into the reeking chest,

Send up an excremental smell

To taint the parts from whence they fell.

The petticoats and gown perfume,

Which waft a stink round every room.

Thus finishing his grand survey,

Disgusted Strephon stole away

Repeating in his amorous fits,

Oh! Celia, Celia, Celia shits!

Johnathan Swift ‘The Lady’s Dressing Room’ available at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/50579/the-ladys-dressing-room

An eighteenth-century dressing room commode (toilet in our modern sense) dressed to full taste and fashion.

In an abattoir, blood, faeces and urine flow plentifully and smells strongly. Some people who see the fear and panic on the face of sentient animals awaiting slaughter sometimes call this wrongly, ‘ the smell of fear’. It is more like the smell of the commonality of life that we deliberately suppress attempts to know because we wish to see ourselves as humans as animals to whom these processes cannot or ever will be applied.

Even when they were applied in the death-camps in Poland and elsewhere, they were disguised as their opposite – as a communal and cleansing shower, with classical music played to the queues of victims as they entered. Humans refined that mechanics of life extinction and waste processing. We can’t do that with abattoirs, hence they are placed outside centres of population or carefully disguised therefrom. We do of course do it in the cuisine of dead meat.

When I became a vegetarian, the first smell I found it difficult to process was that of dead poultry. As 🦃 turkeys line up for Christmas are you happy that they are only eaten to the sound of jingle bells. How about playing it to them as they are killed. Don’t just think about this. Try to sense it as fully as you can.

The Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, aka Lewis Carroll, wrote a wonderful essay against the practice of vivisection, the use of animal life in science. In it, he predicted that if animal life-and-death-processing for the good of a few humans continued as he saw it doing in the nineteenth century, then human beings would eventually be able to contemplate mass slaughter of each other based on refined conceptions of what made human life valuable.

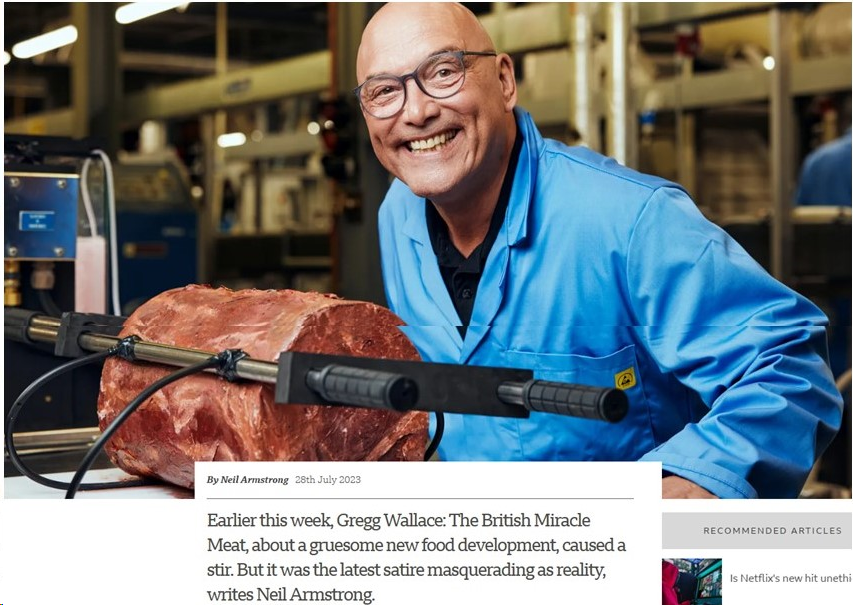

Should mental health patients, the learning disabled, people not valued by ‘master-races and subject to those latter races, and queer people be considered stuff that is wasted and should be seen as in necessity of excretion. All of this was applied in the Third Reich. Jonathan Swift in the eighteenth century wrote a satire recommending Irish peasant poverty and starvation by processing excess children of that class as meat. Recently that store was revived as a programme starring Greg Wallace wandering round a factory processing human flesh as food. People were appalled At the programme but not its message about MEAT.

Have a very merry Christmas 🎄

But really, I say it all

With love

Steven

3 thoughts on “The glass abattoir in the centre of a city”