If you could live anywhere in the world, where would it be?

Daily prompt?

I have seen this question come and go and shuddered at the assumptions that I feared were its motives. Today, I want to confront it, in the light of my visceral response to it, for the world is too much with me. No-one can mention Gaza today without heightening that visceral response and that is for complicated reasons for me. As I tap this response out I hear television coverage of the situation in Palestine. Northern Gaza has been bombed to force destitution and fear among its inhabitants in an effort to persuade that population to move south, where many migrants live in equal fear, and increasing poverty and imprisonment in refugee camps in front of a closed border to Egypt.

Meanwhile, land soldiers now use the hospitals of Gaza City as televisual settings to prove the existence of underground bunkers not yet found, no nothing like them, and to censor the spectacle of the premature babies dying in the huddles that is their only source of mutual warmth that has resulted from the denial of power to the machinery that might offer a chance of future life and home. Many inhabitants of Gaza remember their older family members stories of being displaced from homes they once owned in the area that is now Israel, a homeland reinvented in the twentieth century to house the Jewish people who have lived in centuries of diaspora and have faced threat of extinction in pogroms in Eastern Europe and Russia and in the Holocaust in Fascist Germany.

All of this tragedy is being faced by people for whom our question today must seem really insulting: ‘If you could live anywhere in the world, where would it be?’. For the question facing them is : Can I be sure that I can live (in the sense of make my home) anywhere”, or perhaps “Can I be sure that I will live (in the sense of not DIE an untimely death) at all ANYWHERE?”.

And my title I take from Milton’s Samson Agonistes, the poet’s attempt to make Greek tragic form out of a Biblical story and to dramatise the sense of his own political isolation and frustration as a Republican freedom fighter (in poetry at least). He was, after all, a man who had once been a rebel against an aristocratic class he had at first served, having signed the execution order for Charles I. Now old, blind and feeling as if manacled in a Royalist Britain, and exiled from his homeland of the Jewish tribes of ancient Israel in a pagan prison of idolatrous kings in the then Gaza.

Why was my breeding ordered and prescribed

The links are provided from the text provided at (in case they help – intended I think for school exam candidates): https://www.poetry.com/poem/23855/samson-agonistes. The full text of the drama (with scholarly annotation) is available at: https://milton.host.dartmouth.edu/reading_room/samson/drama/text.shtml .

As of a person separate to God,

Designed for great exploits, if I must die

Betrayed, captived, and both my eyes put out,

Made of my enemies the scorn and gaze,

To grind in brazen fetters under task

With this heaven-gifted strength? O glorious strength,

Put to the labour of a beast, debased

Lower than bond-slave! Promise was that I

Should Israel from Philistian yoke deliver!

Ask for this great Deliverer now, and find him

Eyeless in Gaza, at the mill with slaves,

Himself in bonds under Philistian yoke.

Milton saw himself as Samson because he saw his role as a prophet of the greatness of England as a free state in which Catholicism and monarchy both were overthrown in the name of a non-elite religion as analogous to Samson’s, especially at that moment where Catholic ritual and monarchy had been restored, which were for him ‘bonds under Philistian yoke’. Whilst Milton’s blindness was not a punishment imposed by Philistian Royalist rulers – he was pardoned his role as a regicide; it clearly seemed another appropriate analogy to him that Samson was blinded in order to disempower him as a potential leader of imprisoned Jews for a restored homeland.The point is that here, as elsewhere, Gaza is a setting for feelings of something too grand to be called just homesickness – it was a sickness of alienation from the very source of anything that could be called living at all.

Today, though a people who established a homeland to escape persecution use state terror against a whole population in Gaza because of the actions of a few terrorists not unlike Samson was – and is to be in his glory at the end of this play. Here a Messenger (Mess.) comes to tell Manoa (Man.), Samson’ s father, the news that Samson has ended his life in an act of terror killing many of Israel’s enemies, regardless of their role in his plight:

… Man. Self-violence? what cause

https://milton.host.dartmouth.edu/reading_room/samson/drama/text.shtml lines 1584ff.

Brought him so soon at variance with himself [ 1585 ]

Among his foes? Mess. Inevitable cause

At once both to destroy and be destroy’d;

The Edifice where all were met to see him

Upon thir heads and on his own he pull’d (sic.).

In seventeenth-century England Milton found it easy to imagine himself an exile, without a true homeland because work was a matter not of service but slavery ‘at the mill’. Where though John, ‘if you could live anywhere in the world, where would it be’? In fact, Milton could answer this better than any of the people who have fled Northern Gaza on command of an incoming and merciless army of revenge (I do not dispute their right to feel the desire to revenge nor defend the Philistine yoke of Hamas) intent on reoccupation of the whole of the land of Palestine – including those disputed officially government-less domains of Gaza and the West Bank, though loath to say so publicly.

I think that perhaps we need another context in which to see how a question-setter could come up with the question I grapple with here. Among the rich nations and amongst the rich of even relatively poorer nations, money and status give unparalleled levels of mobility in a global economy. Capitalism respects the boundaries of nations with a differential eye.

If you are poor or displaced by ecological breakdowns brought about by Western and Northern profligacy and unrestrained and unsustainable economic growth at your expense, wars and civil unrest favoured (and sometimes engineered and fuelled) by the West as means of destabilising potential or sitting democratic-left governments, then your wish to live somewhere you choose ‘anywhere in the world’ is treated as ‘criminal or unethical. You might be forced to live in an unsafe prison-hulk or deported to Rwanda, a country lawlessly corrupt and waging war against its own poor.

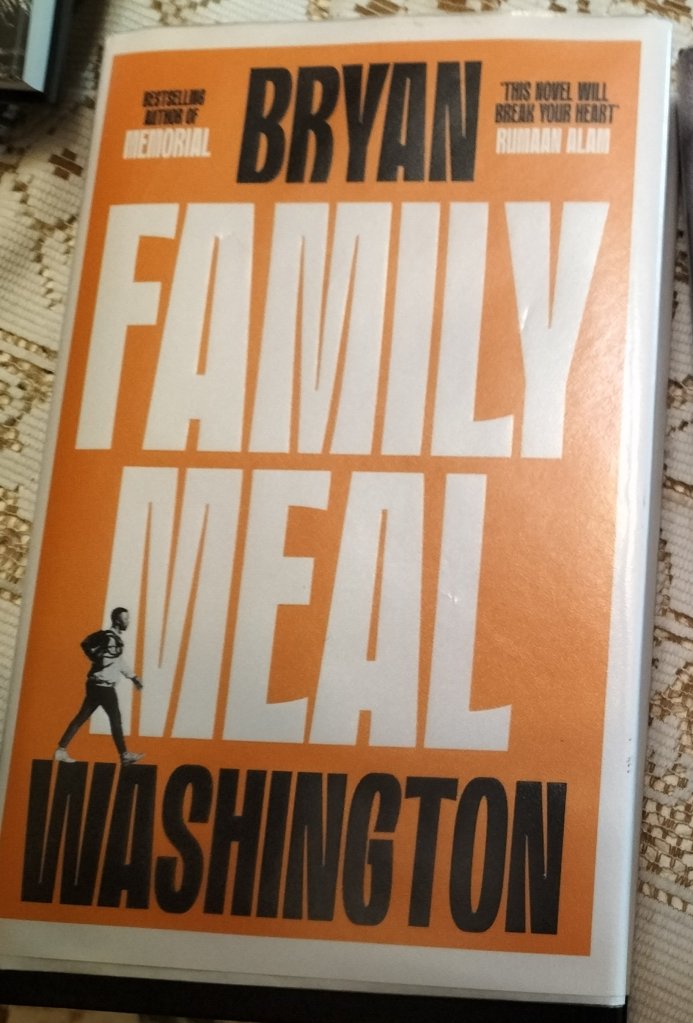

If you are wealthy and of high status the world can be colonised or settled by you, with permanent or temporary homes. you may not even need to be rich for you may serve a multinational corporation, perhaps as a much needed translator or interpreter for international deals, that gives you that privilege in return for a degree of servitude to its needs. This is a world I have come across in the very great novels of Brian Washington, and on which I will blog in their own right later. In particular in both of his novels thus far he has concentrated on relatively disadvantaged black queer men making a ‘home’ (or losing one) with economically valuable and globally mobile Japanese queer men. Now, I think Washington brilliantly handles this scenario which represents the truth of some lives in the Global capitalist world, where one person has restricted mobility (though gets it through a relationship to someone with much greater mobility somewhat) and the other has much.

Washington is brilliant. I think, as I will argue that he uses these fluid settings to discuss issues of ‘family’, ‘home-making’ and so on in a context where those words do not match their original heteronormative uses. I will speak of that later. But the world he addresses is not the product of, or for the convenience of those queered from ‘settled’ norms. Staying in or leaving, returning or not returning to family (even building new senses of chosen family) are the stuff of this novel. But Washington makes this something about the existential questions of being settled or otherwise in oneself or with chosen or unchosen others. Place and time are all functions of feeling a place of safety in which to ‘live’ or better feel at home, or heimlich in the much richer German word Freud uses to describe a place both delightfully familiar and capable of becoming its opposite (unheimlich is Freud’s word for the ‘uncanny’ as translated in English).

I close my eyes, just for a moment, and I think about tomorrow.

And the days afterward.

And what it’ll mean to step through a home, in a brand-new place, where my people aren’t.[1]

The narrator here is PJ, a young man from a Korean immigrant (to the USA) family who is about to experience the choice of leaving his family home and a Black young man, Cam, he was brought up with as a boy and whom he has learned to think of as either a possible lover or one who could never be such because of their joint ‘family’ memories – even though Cam is not biologically or’ ‘racially’ related to him, being brought into his home on the death of Cam’s parents in a car accident. The word ‘home’ is thus a ‘charged word in this quotation, near the book’s end, and in the novel as a whole, as are ‘family’ and even ‘family meals’ for they are a site of mixed cultures, differential familiarities and customs.

This is true of Cam’s relationship to his Japanese former partner, Kai, who appears to him as memories and as a ghost. Living anywhere is a world is a choice in Washington’s novels, though the constraints on that choice are mentioned too. American partners never choose to live with their Japanese ones even when choice confronts them. But Mike, who is Japanese, faces his mother’s belief, and in some senses she is grounded in Japanese identity and loves her son, that his true home is with his Black lover in the States on Washington’s beautiful first novel Memorial.

But these beautiful novels aside, I feel as if this question cannot be asked as if it represented a wish that could be expressed innocently or with integrity. The issue of a migrant poor and displaced is already a global issue and will I suspect become more so. Homes can be destroyed and people sent on mass migrations, sometimes worse when internal ones, or frightened as many Ukrainian and Russian men have been of obligations forced on them by their governments and ideologies of the value of war. So it feels shoddy for me to say where I wish to live ‘anywhere in the world’. But others who answer it I do not judge, for the circumstances of such a wish may well be that of facing terrible necessities of staying at home from domestic abuse to bullying or oppression.

Keep safe if you can, lovely people.

Steven

Xxxxx

[1] Bryan Washington (2023: 282) Family Meal London, Atlantic Books Ltd.

5 thoughts on “‘Eyeless in Gaza, at the mill with slaves’: The dream of a permanent home or the choice of a luxury setting?”