“Everything I had willingly drawn was female. But here, through these coal-mine drawings, I discovered the male figure and the qualities of the figure in action. As a sculptor I had previously believed only in static forms, that is, forms in repose”.[1] Henry Moore said this when talking to James Sweeney in 1947. It suggests that the project to portray coal mining during war time commissioned by the War Artists’ Advisory Committee (WAAC) made a turning point in his artistic career that focused on the gendered nature of his subject-matter. How does this manifest itself in these drawings. This blog looks at this issue in the light of Chris Owen (2022) Drawing In The Dark: Henry Moore’s Coalmining Commission London, Lund Humphries.

Henry Moore sketching two miners at Wheldale colliery in 1942. Photograph: R Saidman

Chris Owen warns us, if not exactly in these words, that Reuben Saidman’s photographs of Henry Moore drawing the miners at work underground at Wheldale Colliery should be judged in their own right as examples of the photographer’s art. He cites Moore indicating that little effective drawing was done by him on the days Saidman visited and were ‘not much use from my point of view’. The photographs were lit, composed and framed in ways that suited the view from the frame set by the camera lens and should be seen essentially as artificial in all these respects. Moore is positioned as if to look as if he were recording what he saw but not from the position and angle relative to his subjects that would really cater for what he needed. In some photographs the marks on the drawing paper can be seen and, in one case were ‘covered with abstract pencil marks, very different from the notebook drawings’. What we see therefore is a kind of stilled theatre, not an accurate record, not least because of the use of a ‘standard press camera’ which created ‘much more even lighting than the miner’s lamps would have produced’ and in particular led to the ‘flattening of shadows’. As we shall see nothing could be further from the effect of the finished works, where light is minimised and shadow maximised, making the figure emerge from the circumambient ‘darkness visible’ rather than be seen directly to the eye in the blanched whiteness of their naked flesh reflecting the camera’s lighting.

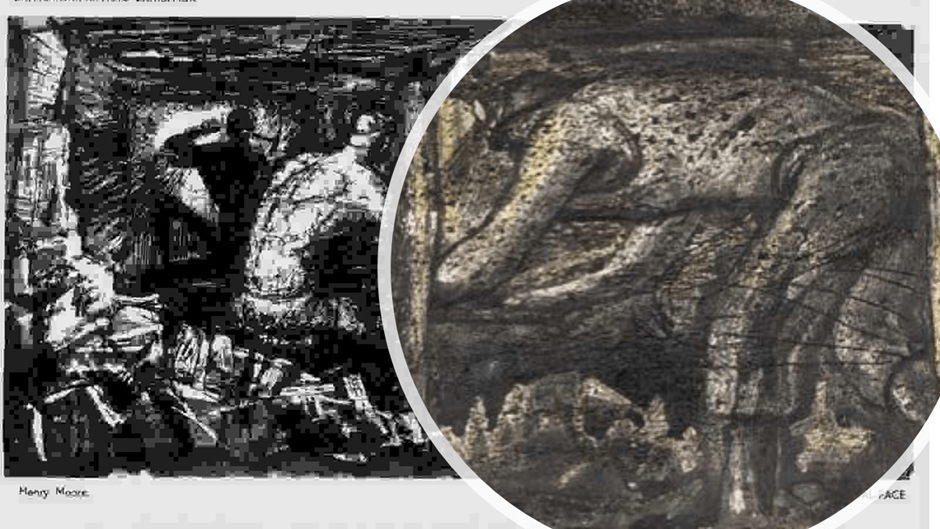

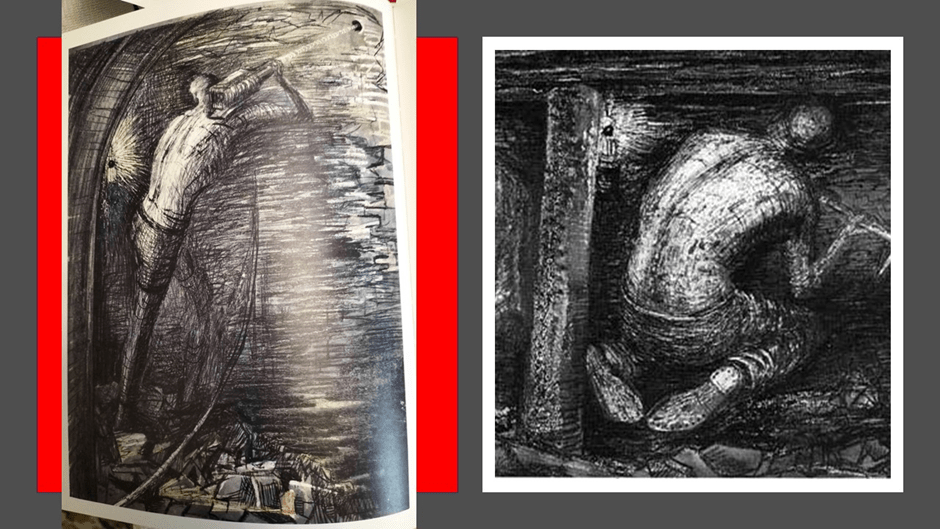

Of course, the finished pieces are very different from the drawings taken in what is called in the book Notebook A, filled with Moore’s preliminary sketches, which ignore the surroundings of the miners, other than in the suggested constriction of space that necessitated certain poses of the drawn bodies and their distribution in relation to each other. Indeed, Owen tells us that for some further stages of the work Moore used the sketches to fake up scenes in wider tunnels on site with miners willing to remodel them or even instruct models, possibly from the Perry Green Home Guard, to copy the poses in his studio in order to work on them with a better view of the anatomical realisation of the postures and poses he quickly sketched underground in poorer light and space.[2] Moreover, we know that just as a camera muse seek an unobstructed view of its subjects, so that each man may be seen unobstructed by each other, the artist, pitprops and other underground architectural obstruction, so Moore would seek the create scenarios and effects using those very things – for his purposes to obstruct vision of the full body of a miner with a representation of a pitprop where it might not have been. We know, for instance, that he uses the way the body of a man might be visually split by a prop was used by him quite consciously to create ‘visual tension’ and strain, the effect perhaps of the man’s motion in the still picture that resulted.[3] See, for instance, the example below:

At the Coal Face: Miner Pushing the Tub (1942) pencil, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour, wash, pen and ink, 33 x 63.5 cm. (see ibid 74 for reproduction in book where tonal effects are darker.

Owen’s book is a very comprehensive analysis of the role of work upon the coal mining artworks that takes in the varied ways in which other influences – from personal experience in World War I and examination of the work of Masaccio as a painter – affected him , in for instance using pit props in a manner similar to Donatello’s use of columns from classical architecture and, Owen thinks, for similar representational and formal purpose.[4] But this book has a sub-text that I want to draw further into the light, whether or not this was Owen’s intention. Speaking to Harriet Sherwood of The Guardian about the exhibition he mounted at St. Albans to launch the book, he says the following, about the exhibition, but it applies equally I think to the book:

Owen said Moore’s coalmining drawings had perhaps been “disregarded in the past, seen as a digression from his sculptural work”. But he added: “They’re beautifully observed, with subtle transitions of light, exactly capturing the miners’ postures and the male form.”[5]

In a transcription of an interview much can be misread. This statement is, in a sense a re-evaluation of Moore that is aesthetic in nature and art-historical in detail, in that it explores how and why an artist known chiefly for his work on the reposing female form taken from idealisations of living figures, where men appeared almost by accident (in that a symbolic family was represented) became interested in male form in action. Yet can that statement also be read to show that consideration of masculinity as a form of a sexed-and-gendered form of being revealed to Moore an interest in male beauty that he otherwise neglected, or even repressed. This is not to case a case for seeing Moore a man who repressed queer sexual interests but to look at how a culture that had seen men as a functional necessity in maintain patriarchal capitalist society as leaders and workers, suddenly is caught short in admiring something beautiful that was not merely functional. For Moore himself, a deeply reserved and repressed man in all accounts of him this must have had resonance too, and Owen provides the evidence for this if not the explicit argument, for a reassessment of how men touched upon his sentient life, even in his own family. Sherwood ends her review quoting Owen again on this subject that takes into account his reserve not only on Moore’s relationship to men abstractly and in particular but also to a politics he somewhat left behind him – that of his father’s socialist and trade union convictions (his father had organised union resistance to improve conditions for miners at Wheldale and was a socialist).

“This was the only time when Moore really explored his background. He doesn’t seem to have been close to his father, but Moore had a lot of sympathy for these miners. He didn’t say much about his private thoughts, so we only know what we pick up from his drawings. But I think this series shows that even as a wealthy and successful artist, Moore continued to value his father’s socialist beliefs.”[6]

My interest then is in the emergence from all these dark shadows of reserve of a kind of restless, disturbing and disturbed beauty recognised in the working male body (in labour, struggles for a just cause in support of making a living home). It is a belief not inherent in a body like that that of the real miners but of ones he had idealised, as he had female form, but in a way that far from settling him, made him aware of an energy that will not rest and disturbed him, in the way that the ideals of male beauty that embodied justice and social love disturbed the society he sprang from. Early in life Moore had been attracted to communism, although this never disturbed the mainstream of his art or his pursuit of the glittering prizes of the establishment, even though he showed care for public values. Though then neither a socialist in any way that mattered or a man who loved men with passion in any way whatsoever, I want to show how his confrontation with male form aesthetically touched on issues dangerously disruptive to the ideal of the man revered in the status quo as a bohemian become a public treasure.

In my title I give a quotation that has puzzled Harriet Sherwood too. Here it is in slightly greater fullness:

“It was difficult, but something I am glad to have done. I had never willingly drawn male figures before – only as a student in college. Everything I had willingly drawn was female. But here, through these coal-mine drawings, I discovered the male figure and the qualities of the figure in action. As a sculptor I had previously believed only in static forms, that is, forms in repose”.[7]

Owen points out that an early study of Moore by Erich Neumann, written from a Jungian psychoanalytic perspective had attributed Moore’s seeming preference for resting, reclining and large female forms to a notion of the archetype of the Eternal feminine associated with a creative underworld of motherly fertility.[8] Male form in contrast, Neumann found I the helmet-head trope, a one eyed hybrid monster that may have its genesis in Homerian and Vergilian Cyclops figures (in Vergil the Cyclops aid the symbolic artist Hephaestus at his forge in the making of cunning art) that is half-machine and owes much to the imagery of Moore’s period – ‘the diving helmet, crash helmet and the gas mask’ – to which Own adds the pit-helmet with its one-eye lamp mid forehead. For Neumann these are ‘death’s head’ figures, so different from creative mothers.[9] They are the fathers however of the late warrior figures of Moore of the late 1950s onwards, in which Neumann found (now making sense of the death’s-head mask period) a manifestation of ‘the most devastating portrayal in all art of a supranatural castration complex’.[10]

Owen has a considerably more nuanced reading (saying Neumann ‘goes too far’) though he does not entirely dismiss these suggestions. What he retains (and me for I am always glad to junk any Jungian gobbledygook) is the fact that Moore finds his training ground for his later warrior sculptures in his ‘coal-mining drawings as a war artist’ and rejoices in something ‘almost like the discovery of a new subject-matter; the bony, edgy, tense forms were a great excitement to make’ (my italics).[11] I love that phrase ‘almost like’ for this this is not discovery but archaeological unearthing in my view that is not ‘new’ but only feels it because it is found in a mode of ‘great excitement’. This is the feeling, I would argue that I named above of ‘the emergence from all these dark shadows of reserve of a kind of restless, disturbing and disturbed beauty recognised in the working male body (in labour, struggles for a just cause in support of making a living home)’.

But, I inevitably ask myself, how did Moore arrive at such an edgy, excited and disturbed distortion of the male body in action from his early work, not even contemplated when he accepted the WAAC commission for otherwise there was no work for sculptors and thence no living. Owen has a lot about war experience but I wish to leave that kind of speculation alone, though I think it could be integrated for this was the war of Wilfred Owen, Seigfried Sasson and other Bohemians too. I want to look at Owen’s suggestion that uses Moore’s own statements about the effects on him of fifteenth-century humanist Italian Renaissance work, as a counterpoint to what he called ‘primitive’ and archaic art, in line with the interests of Picasso, of course. Anne Garrould attributes a general interest in Masaccio in Moore as a means of developing thought on male form and representation – Moore himself said the whites of miners’ eyes, emphasised by coal-black settings and dusted faces reminded him that in Masaccio’s frescoes, he ‘always emphasises the whites of eyes’.[12] Moore was capable of taking this idea to extreme lengths, as in the conversation with a miner, still black from the dust of the Konig Ludwig on the Ruhr valley in Germany, in an exhibition of his work there in 1955, where he said to the miner that the monstrous hybridity of the eye formations of his helmet-head sculptures was ‘something like what your eyes look [like] to the average person’.[13] For me this is definitive and exemplary of the socially inept characteristic of Henry Moore as an artist – who feels that he has the right to cast a man with much less social power than he in the role of the ‘Other’, compared to the ‘average person’. When I talk about Moore as a repressed man it is in the light of this terrible moral stupidity and lack of empathy with human beings outside of their social roles, despite the wonderful androgynous reach of his later sculpture and ‘interior forms’.

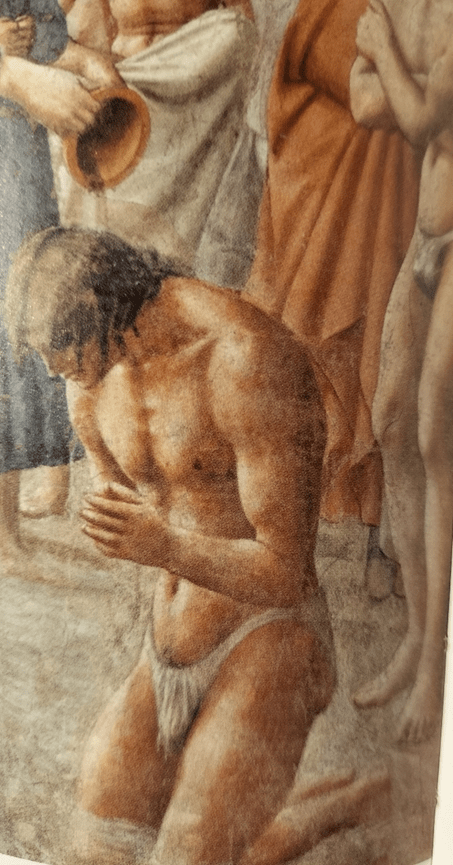

Used in Owen op.cit: 105 (see text above for context)

Owen points to the example from Masaccio in 1424-28 of the Baptism of the Neophytes in the Brancacci Chapel, which we know Moore sawing his visit to Italy. Owen describes these as the ‘most powerful studies of the male physique in Italian art’ and the kind of example Moore could be referring to when he used this painter to illustrate what he meant by the humanist approach to the sculpture of human figures.

It would be difficult to find a more beautiful idealisation of male form than the example above, used in Owen’s book. But this is not realism but truly heightened idealism where the innocence, beauty and strength of the man submitting to baptism is aligned to anatomical and haptic realism in the flesh, casting off water with its invitation for the eye to follow the water poured on him down into the clefts of the man’s torso beyond his navel to the dip which holds the curve of ritual underwear around a shapely groin. The ideal male is one so beautiful that his gift of his body to God is a worthy one.

Owen does not say we shall see that man in the Moore mineworker artworks but I do think that bull like shoulder may be among the qualities of his pitmen. Those pitmen certainly don’t look like those in the well-lit Saidman photograph I start with – any tendency to paunch or body fat being eradicated. Of course the sketches and drawings have other functions that to instance ideals of male form, which have much to do with the distribution of a fulsome sense of human male form in a space too tightly spare and controlled than a such a form requires for beauty. I will go on to talk about this, but the following alone will show that Moore selectively emphasised male form in terms of its ideal heightening of muscle development and body feature, especially of arms and back, but sometimes too of bottom. For instance look at the following details to get some idea of how much attention there is, as in Masaccio, to the development of physique in ideal form, especially width of shoulder and upper torso. If some of the ways in which Masaccio makes his neophyte a thing of beauty and a quality to long for it is the emphasis on curvature and flexibility, the play between what is revealed and what concealed, I see that in Moore’s miners, whose trough clothing (when it has not been abandoned in the heat of the mine, accentuates the beauty of male nude form either underneath it or in the parts it does not conceal.

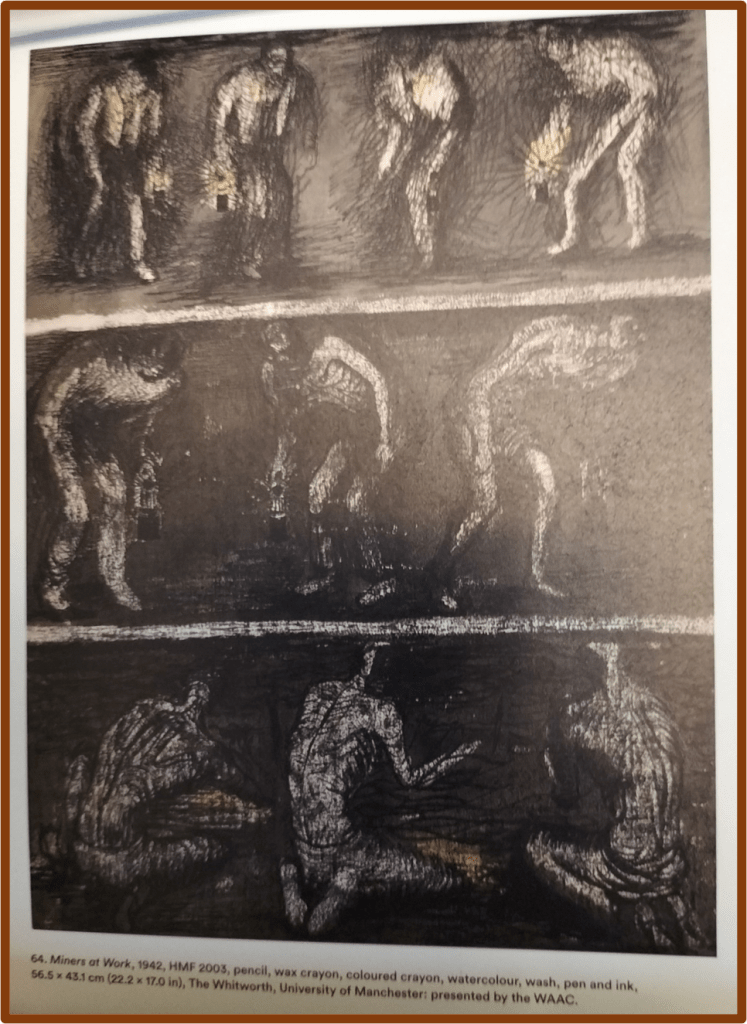

According to Owen, Moore’s miners, especially the kneeling figures (see some below but I don’t confine myself to the kneeling figures for the mounted (on a pile of unstable coal) standing and bending figures have a similar strength of precarious balance. They all ‘possess a dignity and weight verging on the monumental rather than suggesting individual personalities’.[14] In 1941 Moore said in The Listener that this straining to a underlying superhuman was one of the ‘sculptural principles’ of the Archaic Greeks, Pheidias and Masaccio that ensured the retention even in recognisable and realistic human figures of ‘a primitive grandeur and simplicity’.[15] It is, of course, as if men could also be Gods, or if not that Angels, and if not that saints and heroes. These angels might even be of the fallen type – for to Moore, and Orwell who used the same analogy for being underground in a coal-mine was comparable to Hell. At least: “Hell could not be worse … the noise, the dust, the darkness, everything to me was, as I say, just like Dante’s Inferno, like Hell”.[16]

Woven into this mythic context is the idea of the supra-human which may have identified men as monsters too, in the analogy of the Cyclops, in which Moore appears to have had an interest since school and which fitted nicely into the perception of miners wearing underground a pit helmet with a single eye – the lamp that illumined their darkness.[17] The ex-miner and student of the community-learning project The Spennymoor Settlement who became a novelist responded exactly in that way to seeing Moore’s drawing, where death, life, and endurance over generations of a male principle of carrying a burden in a body built for that immortal purpose. Owen cite this poem, of which I give a smaller part:

Dim shapes swathed in darkness,

In darkness swathed in mystery.

Elements:

Darkness, coal, the living flesh

Crouching, crawling, creeping:

The straining of unseen muscles

Against unknown weight.

Unreal men in their inner Hades,

…[18]

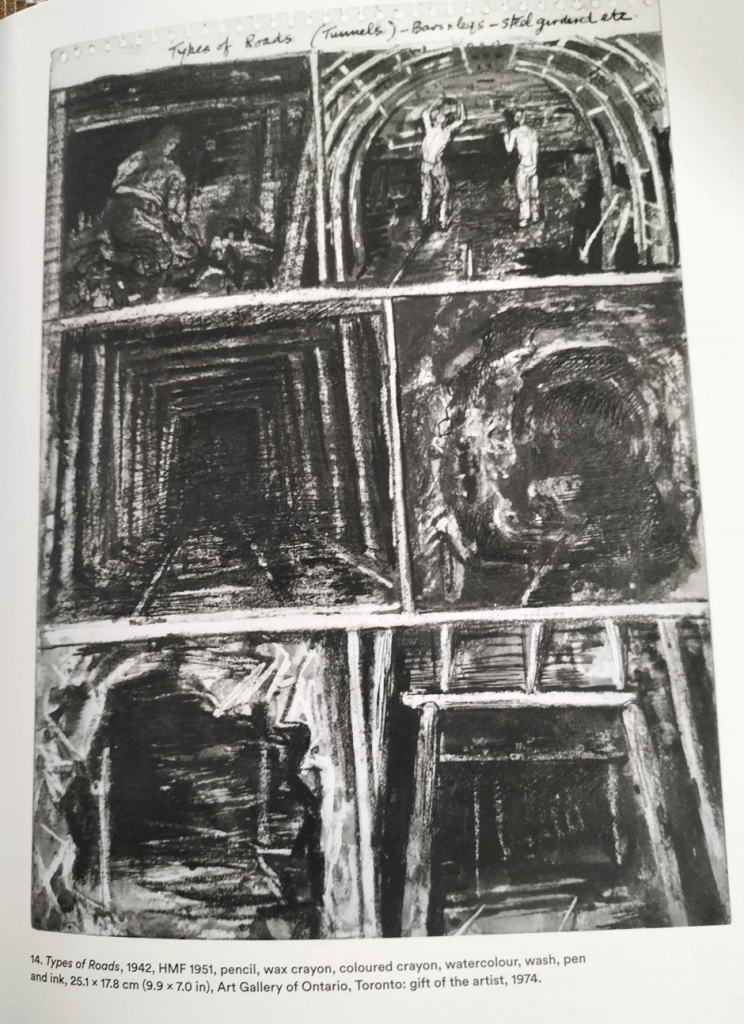

It isn’t likely that Moore saw that poem for it was not published at the time but the creation of an archetype of men supporting the weight of living like inner and/or chthonic demi-gods. My view is, I think – and, of course it is speculative – that Moore in confronting issues that he found disturbing and unpalatable to his self-image as an artist and MAN turns the Masaccio quest for the beauty of male form into something dark in more than one sense of the work – dark in the sense of something difficult to see, read or understand as in the Biblical use of ‘seeing through a glass darkly’ in I Corinthians 13. But the dark is something to fear too. Moore’s interest in capturing the varieties of roads (tunnels) underground seems focused on how to represent the distant dark void to which they apparently led. His representations of the architecture supporting the tunnels seems light and flimsy and at other times under pressure of collapse. It is as if use of light and dark were I some kind of disturbed tension – as indeed in a mine they are. You hear the earth groaning down on you.

Owen op.cit: 29

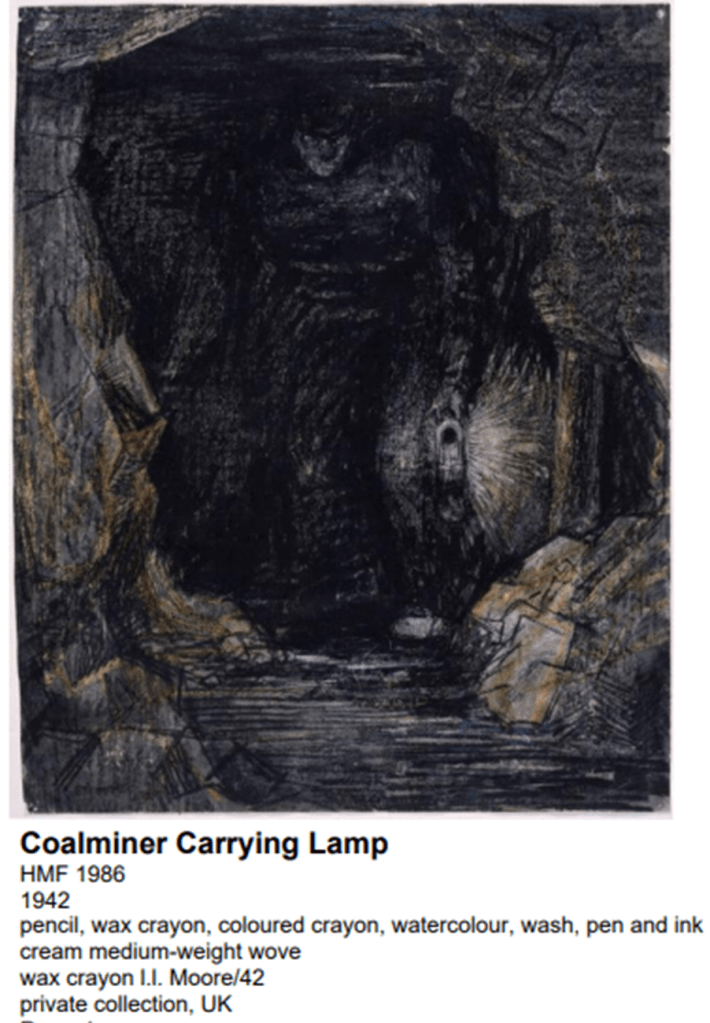

Again I am not saying that Moore primarily was repressing his response to male beauty, though I think that part of the response, but also to the male agencies of his own past, his father, his role as a miner and a representative of working-class politics – and indeed Moore’s ambivalence about coming from the working class himself. Owen carefully shows that, whilst Moore showed empathy for miners and working-class causes from a distance, that distance was absolutely necessary for him. He made no effort to share his work on them with them for instance. In his finest work based on the individual miner, this fusion of man with darkness was definitively the task he set himself, as in these sample annotations to the notebook shared by Owen: ‘Try positions of individual miners / figure walking away / figure walking towards; figure walking bent; …’.[19] Of course an artist does this multi-pose capture of his ‘models’ for pragmatic reasons and more ‘accuracy’ in two-dimensional capture of a real situation.[20] However, in Moore’s finished drawings, and in some of the Notebook A sketches too,[21] they seem to be making a statement of meaning, as Owen also gnomically says, where the figure – and sometimes the direction of movement is ambivalent – is ‘emergent’ from blackness and what Chaplin described in the drawings as ‘mystery’. Note in particular Coalminer Carrying Lamp, which some have argued shadows Holman Hunt’s The Light of the World.

The hugeness of the torso at the shoulders here seems part of the effect of and is achieve as much by the tonal and colour design of the whole page, where the figures boundaries are difficult to distinguish from background. Indeed Owen shows that Moore worked separately on these aspects before integrating them as if an effect greater than just mimesis was intended.[22] I have to say of course that Owen does not encourage me in seeking significance here and not just perfection of mimetic technique. And Moore may seem to talk as if he were just recording phenomena to the eye alone if you ignore the force of the word ‘felt’ in the following, when he says: ‘ To record in drawing what I felt and saw was a new and very difficult struggle. There was first the difficulty of seeing forms emerging out of deep darkness, …’.[23] Only if you emphasise ‘felt’ in reading this will the resonance on what is meant by ‘deep darkness’ emerge. It is as if the seeing were supernatural. Interestingly enough Owen says that too despite an earlier statement, but I think Owen felt the creative thinking about the works changed in their development.

Even if we think this is just a matter of technique that occurred in the revision of the works, Owen’s description of some of the innovative materials and techniques (or both together in the invention of ‘wax resist’) he used shows that, in response to these, his engagement with what these artworks ‘intended’ changed. However, you would have to read Owen’s description of this as I do, with a revisionary sense that Moore saw much more in what he was doing than creating ‘a rough texture and suggested the reflective surface of freshly cut coal’.[24] Decide this for yourself by reading for the book is worth clear and close reading. What I see and feel in the Coalminer Carrying Lamp and more so in the deeply enigmatic Miners Walking into a Tunnel (1942) is something emergent in more than a purely visually realistically representational way – one that does not distinguish in clear ways walking into or out of a tunnel, for what emerges is the relationship of men and man to the void in which masculinity collapses them. Again though I must leave that to you.

These are hard questions. They depend on how one allows oneself to read and prioritise artistic intention and your trust in the fullness anyway of their expression by artists or in deductions from other evidence from art historians. But for me the art matters because it disturbed Moore’s routines, practices and artistic preferences, not least in finding in male subjects much that only has ‘emergent’ meaning for him and his culture and is found only by the contingencies involved in artistic process. It is a place where the grotesque or uncanny representation of the male such as that in Miner at Work (1942) that can be read in so many ways touches on the role of the male as potential but doubtful redeemer as in Miner Carrying a Lamp. Owen sees the former as bearing deep and painful visual memories of World War I gas masks but I so do not want to get into that debate, and will not reproduce picture or Owen’s readings.[25]

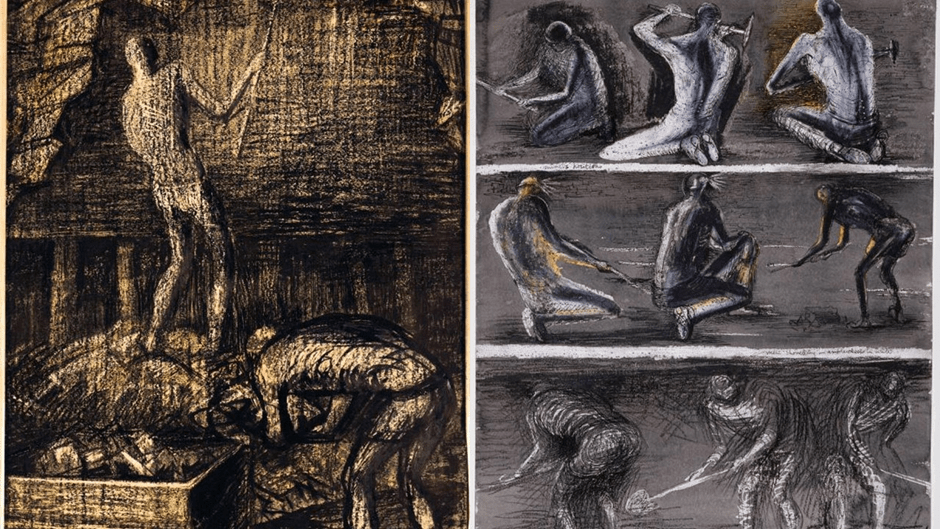

A point I want to end on however is how the distorted masculine figures of the later helmet-heads and warriors relate to the fact, as Owen insists that the miners were drawn with a view to Masaccio’s plastic realism not a Picasso like distortion that not only represented but disrupted both object and viewing subject. I think for me Owen provides an answer but does not quite read his own answer as I do. What interested Moore from the original sketches to later drawing was how the male body interacted with spaces into which it found itself hard to fit or manoeuvre within, which any miner will tell you was the nature of coal-mining. Hence, Moore’s interest in miner’s sitting on haunches or manoeuvring tools in a tight and narrow space in which even their body was contorted. The man who has to bend is a man who accepts the distortions involved as a necessity of earning a living. If there is distortion in these early drawings, and I would say there was, it is because the rule of the system that controlled working-class lives demanded this distortion of them, for space was constricted to save the cost of what capitalists saw as unnecessary labour. Moore used register markers on his page – horizontal white lines in order to convey this restriction and drew poses that emphasised unseen constrictions. The roof always weighs down on FORM, though Moore struggles (with the men he draws) such that he maintain a dignity of form that is still beautiful to eye and soul. But our first view is of the effect of the restriction – especially of ceilings of tunnels that force the men to stoop, in a way readable as stooping to the power of the otherness of the mine, such as Zola made palpable in Germinal.

Even at the stage of Notebook A, I think we see this in preparation. Owen may see the next example as merely a study, though an excellent one of a ‘dynamic miner’ – a man in action – but I think the indication of the drawing’s labelling by Moore is not that he is aiming primarily to ‘strive for a balance between the energy of cinematic action and the sculptural quality of his sculptural work’.[26] What Moore emphasises is the presence and agency of the ‘roof’ which causes the miner in an unnatural pose. He points out why light direction matters by labelling the lamp. And he indicates the tight anatomy of the man under the clothes he will later draw to hide that feature and are indicated here in lightly drawn lines surrounding the shaping of the buttocks. All in all, this sketch prepares us for how the noble form of working-class youthful masculinity becomes distorted – though here but in posture.

Distortions of human male form then are the result of a space and time contingent on the role of labour in capitalism – a relation of deprivation that is not allowed to show in the body but may in the clothed body or clothed parts of the body in the sag of linen. But it is space that triumphs and disorganises human form and dignity of stature in most pieces. The comparison below might show this. In the example on the left in the collage below, Owen thinks the drilling miner is in a pose that is ‘militarily aggressive’. However, I feel this oversimplifies the tension of the piece as a whole, for drilling shot holes for explosives, as we see here, was a dangerous occupation leading to tunnel collapses, and if Moore had not intended us to see this he would not have contrasted the study arcs of the tunnel supports, mirrored by the curvature of a pipe below it, with the rubble and debris of the floor and the jagged architecture of a substance full of fault lines. Nevertheless the man is able to stand, and if his pose is stiffened to withstand the sound and heavy action of the drill, it is not constrained by the roof. Indeed Owen thinks such pieces were recreated in Moore’s studio with models.

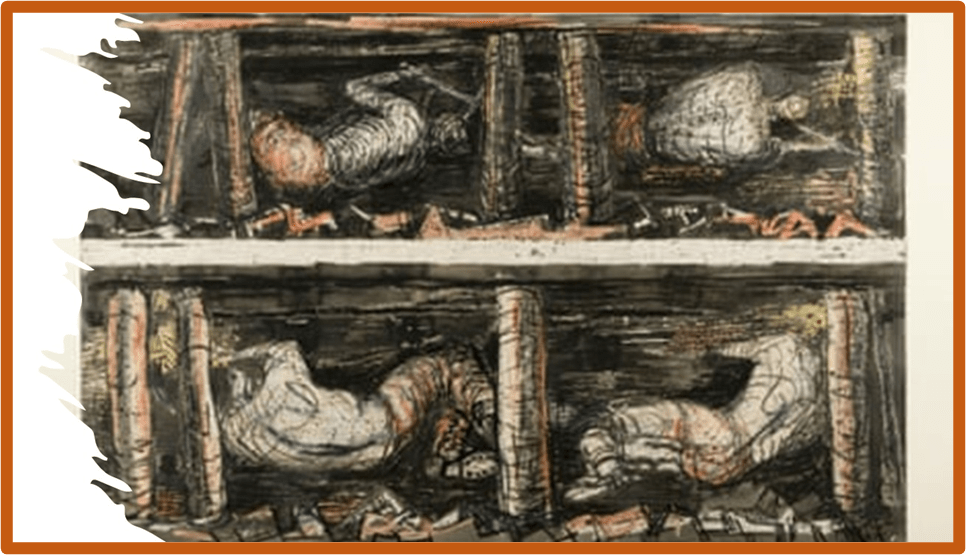

On the right of the collage, however, see the crunched posture of the man attempting to wield and power a pick (the coal must be softer here) where the tunnel support (rigid pitprops) constrains the man more. He is framed, as it were too tightly. And this analogy of using mine architecture as constraining frame (mirroring the frame of the picture) was a common strategy too for painter-miners like Tom McGuinness (the nearest to Henry Moore in idea, style and execution – watch the wonderful video of him on YouTube). Even the head of the man is unnaturally bowed. And what of men cutting coal in thin seams, like those pictured below. Posture, attitude and comfort of an otherwise nobly shaped body are all compromised by the necessities imposed by the market for coal and war-time needs. The pitprops no only frame and constrain but display the fragility of the space hacked out here.

And Henry Moore chose these kind of pictures over all others for his final selection over many more sketches showing the miners comfortable (relatively) in social engagement underground or at the pithead. He seems drawn to find the source of distortions of human male form in work organised for reasons not those of the worker or workers united, a theme on which his father would have been eloquent at home, in the pit (though he was relegated to lamp room work after an accident) or in union gatherings. One of the few overground pictures surviving for development by Moore is characteristically of very young men. See it below.

Pit Boys at Pit Head, 1942. Photograph: Courtesy of the Hepworth Wakefield

I find it very beautiful but very sad. There is no doubt that Moore felt his art took him out of a mining career himself, before, as with these boys, he faced that bleak future – one Sid Chaplin writes about the wish to escape from in his under-rated early novel, The Thin Seam. The boys look at, but barely see each other. There is something deliberately lost in their gaze, and something that challenges the comfort of the viewer, and I think Henry Moore, in the gaze (from one eye alone, of the boy second from the viewer’s right. I feel it even now.

The theme of hellish imprisonment is never far from Henry Moore’s fears in the Mining Drawings nor of the contorted disturbance of his later forays back to the masculine subject from the comfort of rejoicing in his early works of icons of reposing females and happy families. These latter are great works but I think they are morally stupid works, that do not confront those topics Moore attempted to push underground until forced uncomfortably back to the pit and deeper layers of stuff he preferred to be shut from public view or talk. They hide under Jungian ideas of the Anima. I think this is not the case in later androgynous works like ‘Interior Form‘. His moral stupidity is the reserve people speak of in the younger man. This is why I feel him so inferior at that point of his career to Barbara Hepworth – but wow! What an icon of his period and how important he should remain when we examine sex and gender issues in that period. Owen just points to that in underplayed statements such as this: ‘It is noticeable that in his writings and many interviews, Moore scarcely mentioned the impact, in 1922, of losing his father while he himself was still relatively young’.[27]

If you read Owen’s book (which I recommend) I would love to hear feedback discussion from you. I would, even if you don’t read that book. This piece is subjective and speculative in judgement and conclusion but I can see no other function for an unpaid thinker now out of the institutional trap of an objectivity, unlikely to exist in these areas of artistic expression where so much is contingent, even the happenstance that minds may communicate more freely.

With love

Steven

[1] Moore cited in Chris Owen (2022:77) Drawing In The Dark: Henry Moore’s Coalmining Commission London, Lund Humphries

[2] see ibid:55 (for using wider spaces in the mine) & 81 (using models at Perry Green).

[3] Ibid: 75

[4] Ibid: 91f.

[5] Harriet Sherwood (2022) ‘Like hell’: Henry Moore drawings of coalminers’ wartime work on show’ in The Guardian (Fri 16 Dec 2022 06.00 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/dec/16/like-hell-henry-moore-drawings-of-coalminers-wartime-work-on-show

[6] Ibid.

[7] Chris Owen op. cit: 77.

[8] See ibid: 24

[9] Ibid: 124

[10] Cited ibid: 131

[11] Moore cited ibid: 131

[12] Ibid: 91

[13] Cited ibid: 105

[14] Ibid: 90

[15] Cited ibid: 93

[16] Cited ibid: 96

[17] Ibid:126f.

[18] Ibid: 117f.

[19] Ibid: 89

[20] Ibid: 81

[21] See those on ibid: 65

[22] Ibid: 67

[23] Cited ibid: 67

[24] Bid: 69

[25] See ibid 106 -108.

[27] Ibid: 14

Many thanks for your very interesting blog based on my book. Sorry I didn’t spot it sooner – I have been pre-occupied with other issues since the exhibitions based on Drawing in the Dark finished last summer. I have thoroughly enjoyed reading your close analysis of some of the drawings.

As I think you spotted, I was more restricted in the amount of speculation I could put forward than you are able to do in a blog post. As soon as I tried to read beyond Moore’s frequent but often anodyne commentary on his own work, the editor or academic reviewer’s (metaphorical) red pen wisely appeared…

I do think Moore’s approach to masculinity needs more research, but as you could probably see from the book, that is not my specialism. However, I think you might struggle to get much further with a queer reading of Moore’s coalmining images; after all, they were a commission, and he rarely chose to portray men at all. But if you’d like to try, good luck!

LikeLiked by 2 people