What will your life be like in three years?

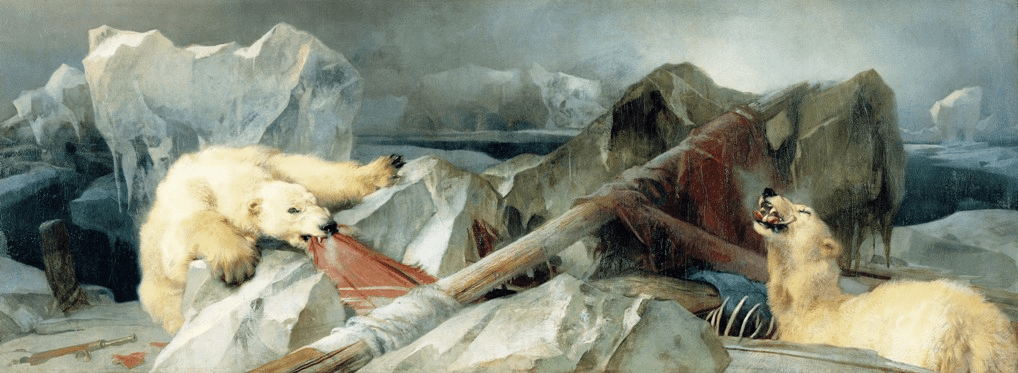

Man Proposes, God Disposes depicts an imagined Arctic scene in the aftermath of Sir John Franklin‘s expedition in 1845 to explore the Northwest Passage but lost in the process. It is by Edwin Landseer – 1864 painting, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9065315

Edwin Landseer’s Man Proposes, God disposes of 1864 is supposedly a lesson to human beings who make plans in a world riven with uncertainty that the disposal of events is not in their hands. The title is rather forbidding for it seems to say that God brings disaster on these human beings by design, as a punishment perhaps for the vanity that makes ‘man’ feel that ‘he is in charge – and although ‘Man’ is meant to be used without gender specificity here, it is clear that it Man Proposes, God Disposes is male hubris that has been targeted in the shape of the Franklin expedition to the Arctic. It also allowed Landseer to paint animals engaged in animal behaviour. However, there is a more than a degree of moral emblem in that behaviour. The Polar bear on the left, rather irrationally for a bear, pulls and tears at the red sails that should have enabled Sir John Franklin’s passage through Arctic waters but has become torn and ragged cloth – remarkably well preserved in colour and design despite its fate.Red was possibly used here so that torn off patches of that sail might recall a pool of blood, as in those red marks to the left of the bear on the left and be seen as blood at first horrified gasp. That balances the bear on the right who is chewing a very bare bone from the skeletal rib cage poking up from the ship’s remains beneath his paws. How the flesh that was in those bones has disappeared, whilst the cloth of the sail remains so fresh is an unanswered question, particularly since the bear enjoys and triumphs in only dry bones. I would suspect that Landseer fell shy of painting bloodied flesh, though he liberally dashes pink stains to the fallen flag pole, as a sop to a squeamish Victorian audience.

God aside, the point is that three years is time enough for massive change. Franklin’s third expedition left port in 1845. Franklin himself died in 1847, and his crew died slowly after him of hypothermia and dysentery, rather than at the paw of a bear. A lot then can happen in three years that you were not expecting. So whatever I propose as likely to happen does not mean I can dispose things so that events we have proposed to be our aim occur or, if they do, the manner of their occurrence.

Moreover, no-one knew better that Great Expectations can be either frustrated or their nature, cause or means of disposal misread than Charles Dickens who wrote a great novel about it. He probably satirised his father in this respect in the wonderful Mr. Micawber in David Copperfield. Micawber’s view of life wasn’t favourable to planning for goals though either, since he too saw he might not not have the power of disposition. In its place, he had a belief that ‘something would turn up’. merely predictive of success in a hopeful way than suggestive of great planning or ambitious proposals for action.

‘Something will turn up’. Mr Micawber outward-bound

Successful people like Dickens and Landseer still had a feeling that people who fail to plan, plan to fail – although Micawber does turn out alright in the end. But though the self-consciously successful play with the fascination of the unpredictability of the world, they still feel that they must and will propose and predict goals for themselves and propose to meet them despite the uncertainty of success and still have reason to believe their great expectations will be met. No doubt John Franklin set out in 1845 sure he would find the North West Passage and cross through it. These days we are all meant to be like that. The most common question in interviews is still: “where do you see yourself in five years time?”.

There are lots of reasons for it. The social-behavioural psychologist, Albert Bandura wrote a wonderful book full of evidence that believing one can do a thing is a great predictor of you actually doing that thing. He called that quality self-efficacy. The relationship between a self-efficacy belief and success is not however a magical one. It motivates training and effort and mitigates against disappointment and difficulties. It keeps motivation going. Neither is it a certainty. Self-efficacious people still fail sometimes.

However another psychological trait also comes into play. The evidence in social psychology shows that people tend to believe that if someone fails in something or falls into destitution it is likely to be their fault or because of a deficit in them. If only they stuck to their goal despite a setback (like me), we are likely to think. Told stories about a failure they might themselves experience, rather than one about someone else’s ‘experience’failure’, people tend (or have a ‘self-serving bias’) to see objective and external reasons that mitigate the failure rather than attributing it to some subjective fault as they do with others. Internal faults it seems are something we more normally attribute to others not ourselves. Psychologists call these factors aspects of the fundamental attribution error (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fundamental_attribution_error). It suggests that we attribute internal deficits to the others who fail in life in some way by our criteria at least but only external understandable problems and barriers to explain our own failures in life, such as goal that have not been achieved.

It matters because the act of seeing oneself as one will be in three years relates to beliefs in one’s own efficacy and expectations that no great external barrier will stand in our way. At my age, 69, I can’t absolutely rule out the possibility that I will not be alive at 72 but I do expect to be so. But as one passes mileposts like retirement , goals no longer get supplied by external agencies like workplaces or employers and friends young enough to be still working tend to drop away because their lives are busy with the demands of that work. There are less external factors in one’s life to keep your goals less subjective and determined by necessity by the strength of one’s will and belief in one’s agency in the world let alone efficacy rather than by external necessities, given at least that a pension remains a sufficient income to sustain life and the world does not flood and burn beforehand. And even a belief that sustains even fictive attribution of basic qualities of being good enough and sound enough to meet all challenges will help but requires a certain amount of imaginative bounce in one’s grasp of the world that I found easier when I was younger.

In truth, I have no great confidence in being motivated to finding new goals or in maintaining progress towards old and new goals. That is an internal work in progress as I pull out of a recent severe attack of anxiety and depression that isn’t lifted enough quite yet, but I am on the way I think, to set imaginable goals for the future and to imagining too the will, capacity and motive to achieve them. Just surviving is not enough, is it? In some ways I think one needs a touch of Micawber’s belief in that ‘something’ that will ‘turn up’.

But meanwhile the battle must be to set goals and derive plans, to sustain the embers of self- efficacy and self- forgive a need for a self-justifying degree of fundamental attribution error. Some psychological knowledge systems like those sometime make one believe that a too hungry concern for objective fact is not what you need to rebuild your internal personal world of self-belief but the ability to create fictions about oneself as something ‘outward-bound’ to new worlds and believe in them – pulling on your gloves to face the world just as Wilkins Micawber does. For do not such fictions become facts if we believe in them strongly enough. After all, it has convinced all of us so often, if we are honest, that ‘something will turn up’, even in a world we know to be uncertain. The gods may not dispose to allow us what we propose, as Landseer suggests, but surely they do not always send in the polar bears to rip you apart and lick your bones. Do they?

With love

Steven