In a review of a book of poems by Paul Muldoon in 2015 Fran Brearton in The Guardian writes that: ‘In a 21st-century context where everything seems instantly “knowable” for everyone, where we are “assailed by information”, what is “worth knowing” or what remains unknowable have become pressing questions. … The earth … is now also a Google Earth, and “all ye need to know” there at the touch of a touchscreen’.(1) Brearton contrasts this cornucopia of data, including ‘filthy data’ (erroneous and / or badly presented information that clutters around some gems) with the view of Keats, as the writer believes it to be, from The Ode on A Grecian Urn, which I cite in my title.

But Keats in that poem is not asserting what he believes to be a known truth but supposedly quoting what he thinks a Greek vase is saying. Even an ‘urn’, when it is a speaking character in literature, need not be thought to possess the only thing worth knowing, whatever its age and Classical authority. The poem starts by showing a plethora of questions that the urn prompts to someone gazing at the storied relief around its form:

What leaf-fring’d legend haunts about thy shape

Of deities or mortals, or of both,

In Tempe or the dales of Arcady?

What men or gods are these? What maidens loth?

What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape?

What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

See: https://poemanalysis.com/john-keats/ode-on-a-grecian-urn/ for full text of poem

Keats allowed people to believe, following his experience of seeing the Elgin marbles that classically sculpted work was of cold white and pure marble. Nothing could be further than the truth of a real Grecian urn.

To which questions the urn is silent, speaking when it is imagined to do so only to say, ‘Admire me, find me beautiful and equate my beauty with all the truth you will ever need’. I once loved a man who said to me that he mustn’t be questioned. ‘I love you’ he said, ‘that’s all you need to know’, his tone rising to frustration and anger. Within a week of that time he had finished his ‘struggle to escape’ shutting off all hope of ‘mad pursuit, although even sane pursuit was beyond my grief at the time. When people offer you only one thing ‘you need to know’ you can sure that is because they want the rest to stay secreted and that the one thing is, and was, a lie anyway.

If that is true of urns, equally unperturbed in their undisturbed beauty on which they, in their shape and simple, but tasteful, decoration (today more redolent of Bauhaus – without the belief in left politics of course, than Delphi), then how much more so of frail human beings. You do not HAVE TO BELIEVE in the probity of either.

What the urn teaches is that it is better to be passionate than fulfilled, better to be forever hungry in our wasted generations that to be consummated on earth with a peopled happiness. I believe that Keats had some criticism of the vase to make when he called it ‘COLD’: ‘Cold pastoral! / When old age shall this generation waste, / Thou shalt remain,….’. To be thus self-sufficient is the dream of narcissism, whether in art, life or the conduct of relationships. It is an untrue dream even for the urn which must have protested at its long burial before being unearthed. But, for a moment it relishes its power in denying fulfillment to others.

Brearton’s question is still valid. In a world apparently full of information how do we choose what is worth knowing, for its utility, or even for its truth and beauty. Be sure of one thing. It is never ever ONE THING that needs to be known for the truth lives in multiplicity and diversity not in false unities that serve the interests of the few not the many. Keats never committed to politics, as Shelley did, being too busy loading every rift with ore’ as he advised Shelley regarding his poetry of vast abstract yearning for the GOOD for the MANY. I think in 1835 Browning was thinking of them both when he has his character, Paracelsus (based on the medieval alchemist of that name and in the dramatic poem Paracelsus), say:

Make no more giants, God! / But elevate the race at once! We ask / To put forth just our strength, our human strength. / All starting fairly, all equipped alike, / Gifted alike, all eagle-eyed, true-hearted — / See if we cannot beat thy angels yet! / Such is my task. I go to gather this / The sacred knowledge, here and there dispersed / About the world, long lost or never found. And why should I be sad, or lorn of hope.’

Available as full text of play: https://archive.org/stream/paracelsusofrobe00brow/paracelsusofrobe00brow_djvu.txt

Look how multiplicitous and diverse or ‘dispersed’ Browning’s view of knowledge is and how dispersed, and based in a belief in human rights. True, Paracelsus, as long as it is, has few moments of poetry as great as Keats, though it has some that rival Shelley, but I think it struggles to move aspiration to knowledge in the correct direction. Now that direction is that of a hard research in many places – though not in books, as with Goethe’s Faust (indeed Browning is clearly indebted to that model – filtered through Thomas Carlyle’s take on him) but in interaction with other people – with humanity in the broad and populous; and in the wisdom that huge vessel contains. The truth that may long-windedly arise in Paracelsus is that knowledge is never complete or resolved into unity but must be pursued anyway.

Brearton’s point, however, about the age of Google remains. The internet provides knowledge of things we do not know instantaneously and that knowledge comes in an unsorted mass – together with filth and unsatisfying but sometimes luscious fillings. The response of the architects of digital knowledge databases has been the concept of curation, which has meaning in particular for systems thinking in large organisations, but it can be applied to the management of personal knowledge too when it comes in vast, easily attained, quantities that are unsorted for quality and relevance. When such systems cite ‘relevance’, they do not mean a thin application of that criteria, for in a changing world what is relevant to any problem changes too and opportunities are missed in the process. the overall title gicen to the selection process is CURATION, and although this is NOT the same process that goes into making a great art exhibition< both processes are analogous and both can be done badly by a too rigid or mechanical view of relevance and ignorance of contributions from the previously unrecognized elements in a knowledge system or network. I found this simple definition of organisational curation helpful:

When we say “curation,” we’re not talking about managing warehouses full of ancient artifacts or conjuring up images from the movie “Night at the Museum.” Rather, it’s more like the kind that you used to see in libraries. Only instead of meticulously organizing and maintaining long, shadowy stacks of musty old books and magazines, we’re talking about knowledge curation: the care and feeding of an organization’s critical knowledge.

No matter how advanced the level of automation, knowledge still can’t take care of itself. Keeping organizational knowledge relevant and up-to-date requires adult supervision. Unfortunately, in many organizations, such oversight is extremely rare. If this sounds like your organization, a knowledge curator may be just what the doctor ordered.

What is knowledge curation?

Knowledge curation isn’t just another process. Nor is it just another a system. Rather, it’s a whole new mindset, one that should define the core activities of the 21st-century enterprise.

Think about it…From: https://aksciences.com/knowledge-curation/

- How much knowledge is swirling around your organization?

- How much of that knowledge is “junk” that keeps clogging things up and slowing everything down?

- How much of your personal and organizational knowledge is valuable, but goes unused?

- How much time and resources are wasted re-discovering the same knowledge from scratch?

- Even if that knowledge is shared, how much of it is misapplied?

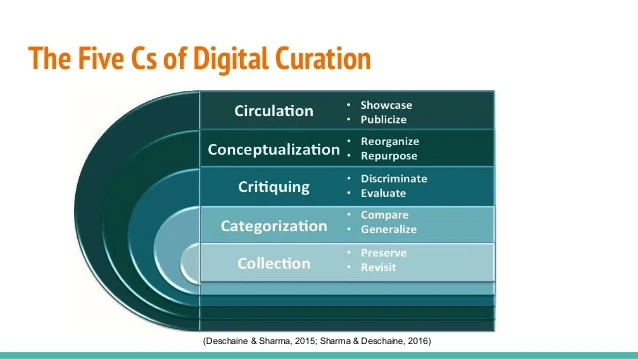

And, though this knowledge comes from surfing the web, such knowledge can yield gold if integrated with a purpose. Take another piece of knowledge found in the same way – an isolated slide found from Bing images, that, if not read too mechanically can help develop good curation practice with any overwhelming source of knowledge, so that we do npot rely on anyone saying to us, from the top-down, this is ‘the one thing you have to know’: usually followed swiftly by the tacit assumption that it is to ‘do as I say’. The model below has five categories of activity involved in Curation rendered as a mnemonic:

- Collection of data / knowledge

- Categorising data / knowledge

- Critiquing data / knowledge

- Conceptualizing data / knowledge

- Circulation of product

This can be thought of as a series of steps but it should, if that is the case, be treated flexibly – not ignoring new data collected while say ‘conceptualizing – both organising the sifted knowledge and applying it to a purpose’ – and, provided it is thoroughly processed (categorised and critiqued) it may force a late re-conceptualisation or change of mind.

Of course, curation as a process can become as desiccated by mechanised application as any other formulaic way of dealing with knowledge. But that may be because we become jaundiced about the beauty of sharing what we know and happy that its incompleteness as knowledge is not something that makes it worthless as Faust believes in the beginning of Goethe’s dramatic poem of that name, but something that makes it warm, living and worth carrying on with BECAUSE it involves prizing others. But crabby old Faust does express the acedia of the knowledgeable so well lets end with that (2). Goethe, unlike Christopher Marlowe, makes his Faust a rather comical figure so that we can enjoy his failure to grasp that his experience is not everyone’s.

These ten years long, with many woes,

I’ve led my scholars by the nose,—

And see, that nothing can be known!

That knowledge cuts me to the bone.

…For this, all pleasure am I foregoing;

Goethe Faust (Part One, Scene 1): See: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/14591/14591-h/14591-h.htm. Illustration from same source.

I do not pretend to aught worth knowing,

I do not pretend I could be a teacher

To help or convert a fellow-creature.

Then, too, I’ve neither lands nor gold,

Nor the world’s least pomp or honor hold—

No dog would endure such a curst existence!

Faust thinks, as a result ‘magic; is the one thing worth knowing. But, as the thirster after omnscience, Goethe himself, knew you never know enough and never exhaust the sources of knowing you might previously have ignored as past thinkers have.

With all my love

Steve

(1) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/feb/06/one-thousand-things-worth-knowing-paul-muldoon-review-seamus-heaney

(2) For meaning of acedia see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acedia