Describe a family member.

My husband does not want to appear in my blog and my parents died a dozen years ago. Their siblings live a long way away from us and aren’t that interested in keeping in touch. Thus I have to fall back on Daisy, for I will restrict my working definition of ‘family’ here to living and love-bearing beings that actually live together. That takes a lot of assumptions about how ‘family’ thus defined could mean much, but at least it resists the temptation to write as if family were just a biologically defined thing.

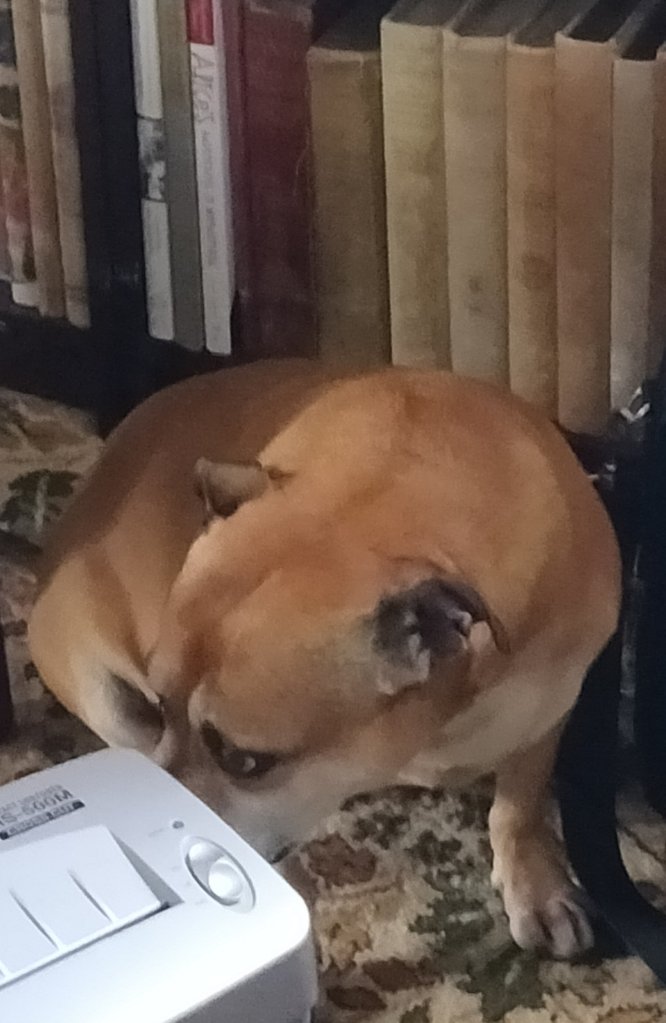

Daisy’s age is literally unknown. We rescued her from a holding kennel where she lived quite badly and came to us with quite a lot of health problems. Now she might rather dominate the house though her nervous state makes her prone to anxiety conditions that, even after 5 years with us, we don’t really understand. She hates overt attention, even the pointing of a mobile phone lens and will hide from that attention. Below she is trying to use the limited shield of space between a paper shredder and the bookcase.

She is however, a camera lens being out of sight, very loving to humans though not so to dogs, a behaviour we can’t manage to train out of her. She dislikes the cold outside and despises rain, often turning back from a walk soon after starting if she has assessed we are happy that she has toileted herself sufficiently. Much of the time we indulge that, though I would prefer more personal exercise with and for her.

But family is something I can’t assume. The biological family has always been based on a fiction in which the transmission of genetic information is read as if it represented a continuum of affectionate bonds and which represents the true meaning of those bonds regardless of lived experience. The highest accolade to which other groupings of people aspire, such as work colleagues in a business or service is that “we’re all FAMILY here’. It is an accolade worked upon and sometimes a behavioural response expected of, and imposed on, some group members.We see Daisy as the very living embodiment of loving bonds, however dependent on covered love for I think it is not only that.

However, family is an uneasy metaphoric base to describe some affinities. Kate Millet was my hero as a young person at university. Her novels and autobiographical work showed affectionate bonds at their maximum not in families bound by biology and legal inheritance but by choice, openness to the person not the label and freedom from conventional legally inscribed living conditions. In one piece in her autobiographical novel Flying she describes the patterning of body muscles required for a child whose developmental needs extended to this done by all of the members of her extended chosen family living in a London ‘squat’ rather than by the mother alone. It is neat how Millet uses the idea of patterning.

Millet’s point was that people learn to relate by observed social models, patterns indeed, that were used to implicitly develop their personhood, including sexed and gendered personhood, and patterns of relationship building, maintenance and ending, when necessary. Her idea was that chosen rather than biological family helps to build loving relationships that are sustaining but which bear change and offer independence to members to make those changes, that are necessary to them.

When we talk about a pet as a family member we may fall back into viewing the family as a space in which love between members is expected and in which true mutual support is dependent. We use the excuse of mutual need of love between us to pattern the animal to human needs in doing so, and if not, we abandon it, as it appears Daisy was abandoned. This scenario appears to be what attracted Lemn Sissay to Kafka’s Metamorphosis story and inspired a play he wrote recently and on which I have blogged. He saw the story as being about how one family alienated its affections from an adopted son by seeing him as an animal and vermin. He seems to believe this was analogous to his adoption experience.

I think that is why I am suspicious, even in myself, of talking of pet ownership as an analogous thing to family relationship. That is not because, as it is for some, because I believe the distinction between animals and humans is sacrosanct, but that the difference in relationship is implied already in the notion that we own pets. We demand behaviour of them that does not allow them to develop as an independent adult of their own species. The relationship either creates subservience or infantilisation in the animal, the latter often observed in the use of baby talk to animals.

But in many ways my dog is a chosen family member, still, despite all this and despite her lack of independence and freedom such as one might think an adult dog longs for. Her supposed independence is, of course, actually strictly within the limits of dog behaviour that humans expect of them. But that is so too of some other relationships between humans. Indeed having started writing this, I am finding it quite disturbing.

I can think of no better place than here to stop therefore.

With love

Steven

Yes b/c he or she IS!

LikeLike

Most definitely is a part of your family. ❤️

LikeLike

Nice post ✉️

LikeLike